History

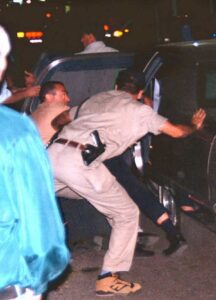

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was fatally shot after attending a peace rally in Tel Aviv’s Kings Square, Israel on November 4, 1995. He succumbed to his injuries during surgery at Ichilov Hospital in Tel Aviv. The assassination occurred as Rabin was leaving the rally. The killer was Yigal Amir, who was against the Oslo Accords. The rally, held at Kings of Israel Square (now Rabin Square), supported the peace agreement. As Rabin descended the city hall steps towards his car, Amir fired three shots with a semi-automatic pistol. Two bullets struck Rabin, while the third slightly wounded Yoram Rubin, Rabin’s bodyguard. Rabin was rushed to Ichilov Hospital but passed away curing surgery, due to blood loss and lung damage.

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was fatally shot after attending a peace rally in Tel Aviv’s Kings Square, Israel on November 4, 1995. He succumbed to his injuries during surgery at Ichilov Hospital in Tel Aviv. The assassination occurred as Rabin was leaving the rally. The killer was Yigal Amir, who was against the Oslo Accords. The rally, held at Kings of Israel Square (now Rabin Square), supported the peace agreement. As Rabin descended the city hall steps towards his car, Amir fired three shots with a semi-automatic pistol. Two bullets struck Rabin, while the third slightly wounded Yoram Rubin, Rabin’s bodyguard. Rabin was rushed to Ichilov Hospital but passed away curing surgery, due to blood loss and lung damage.

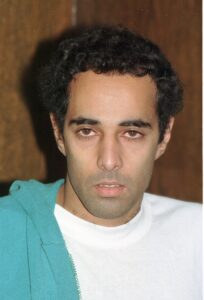

Yigal Amir, a 27-year-old Jewish law student, was linked to the far-right Jewish group Eyal. He was arrested by Israeli police at the scene of the shooting and subsequently confessed to the assassination. During his arraignment, he explained that he killed Prime Minister Rabin because the prime minister wanted “to give our country to the Arabs.” Amir was apprehended on the spot and later sentenced to life in prison.

Yitzhak Rabin, who was born in Jerusalem, played a pivotal role in the Arab-Israeli War of 1948 and was the chief-of-staff for Israel’s armed forces during the Six-Day War in 1967. Following his tenure as Israel’s ambassador to the United States, he joined the Labour Party and was elected prime minister in 1974. During his term, he led negotiations resulting in the 1974 ceasefire with Syria and the 1975 military disengagement agreement with Egypt. Rabin resigned from his position in 1977 due to a scandal related to maintaining bank

accounts in the United States, contrary to Israeli law. He later served as the defense minister of his country from 1984 to 1990.

accounts in the United States, contrary to Israeli law. He later served as the defense minister of his country from 1984 to 1990.

Then, in 1992, Rabin was the leader of the Labour Party, taking them to an electoral victory. Once again, he became the Prime Minister of Israel. The following year, he signed the landmark Israeli-Palestinian Declaration of Principles alongside Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, and in 1994, they reached a formal peace agreement. In October of that year, Rabin, Arafat, and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Tragically, Rabin was assassinated in 1995. Shimon Peres, who was serving as Israel’s Foreign Minister at the time, was appointed Acting Prime Minister after an emergency cabinet meeting. It was such an unnecessary attack.

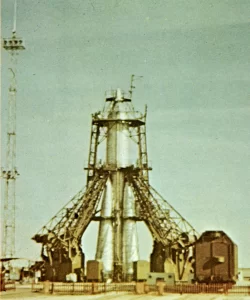

As in most new ventures, there is risk involved, but sometimes it seems like the risk is too much. When the race to put a man in space began, the fight was on between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was a fight that would eventually be won by the Soviet Union…but at what cost. Putting a man in space was going to be a big deal, but no one knew if space was a safe place, or if humans could even survive in space. It was an unusual dilemma, and it needed an unusual solution.

As in most new ventures, there is risk involved, but sometimes it seems like the risk is too much. When the race to put a man in space began, the fight was on between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was a fight that would eventually be won by the Soviet Union…but at what cost. Putting a man in space was going to be a big deal, but no one knew if space was a safe place, or if humans could even survive in space. It was an unusual dilemma, and it needed an unusual solution.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet space program utilized dogs for sub-orbital and orbital space flights to assess the viability of human spaceflight. These dogs, including the first animal in space, named Laika, were used to orbit the Earth, and underwent surgical modifications to collect vital data for human survival in space. The program often selected female dogs for their anatomical fit with the spacesuits and mixed-breed dogs for their perceived resilience, but there was just one problem. The dogs didn’t really understand what was going on, and there was no human to calm them down.

Laika, a part-Siberian Husky, was once a stray wandering the streets of Moscow before being recruited into the Soviet space program. She was used to little human contact. Nevertheless, she got used to it is the space program. While in space, she endured several hours aboard the USSR’s second artificial Earth satellite, sustained by an advanced life-support system. Electrodes connected to her body transmitted vital data to ground scientists about the physiological impacts of spaceflight. I just don’t see how poor Laika could have possibly understood all of this. Unfortunately, Laika died due to overheating and severe emotional stress.

During this period of testing, the Soviet Union conducted missions that included at least 57 dogs as passengers. Several dogs were sent on multiple flights. The majority survived, with most fatalities resulting from technical

failures within the test parameters. Laika was a notable exception, as her death was anticipated during the Sputnik 2 mission orbiting Earth on November 3, 1957.

failures within the test parameters. Laika was a notable exception, as her death was anticipated during the Sputnik 2 mission orbiting Earth on November 3, 1957.

In preparation for the first manned Soviet space mission, over a dozen Russian dogs were sent into space, and unfortunately, at least five died during the flight. I think that if it were me, I would be pretty apprehensive about going into space after five dogs had died trying to do so. Nevertheless, on April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet cosmonaut, made history as the first person ever to journey into space. Traveling aboard Vostok 1, he completed one orbit around Earth before safely returning to the USSR. While it was a man that made history as the first person in space, it was a dog name Laika that actually paved the way…giving her life in the effort.

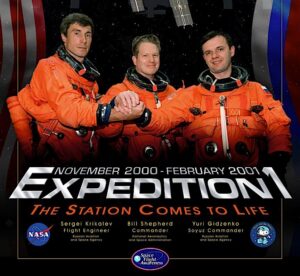

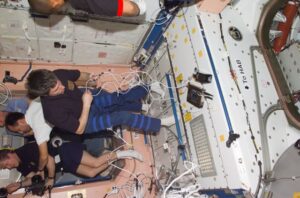

I think most people who followed the building of the International Spece Station were excited about this new venture in the history of space travel. The idea of men and women living and working up there for extended periods of time was amazing…especially when you considered the fact that they would be from multiple countries. Finally, on November 2, 2000, the first residential crew arrived to basically take possession of the International Space Station. The arrival of Expedition 1 heralded a new era of international cooperation in space and the start of the longest continuous human habitation in low Earth orbit. The fact that it is still going on to this day further adds to the enormity of the accomplishment.

I think most people who followed the building of the International Spece Station were excited about this new venture in the history of space travel. The idea of men and women living and working up there for extended periods of time was amazing…especially when you considered the fact that they would be from multiple countries. Finally, on November 2, 2000, the first residential crew arrived to basically take possession of the International Space Station. The arrival of Expedition 1 heralded a new era of international cooperation in space and the start of the longest continuous human habitation in low Earth orbit. The fact that it is still going on to this day further adds to the enormity of the accomplishment.

The space agencies of the United States, Russia, Canada, Japan, and Europe agreed in 1998 to collaborate on the ISS, and its initial components were launched into orbit that year. That in and of itself is amazing. For all these nations to agree to work together to benefit mankind is awesome. Five space shuttle flights and two unmanned Russian flights delivered many core components and partially assembled the station. Yuri Gidzenko

and Sergei Krikalev of Russia, along with NASA’s Bill Shepherd, were the chosen crew for Expedition 1.

and Sergei Krikalev of Russia, along with NASA’s Bill Shepherd, were the chosen crew for Expedition 1.

The trio reached the ISS aboard a Russian Soyuz rocket launched from Kazakhstan. Expedition 1’s tasks primarily involved constructing and installing various components and activating others, a process that proved challenging at times. In one process, for instance, the crew spent over a day activating one of the station’s food warmers. That was probably motivated by hunger!! Of course, I’m sure they had temporary rations available…just in case. During their mission, they received visits and supplies from two unmanned Russian rockets and three space shuttle missions, one of which delivered the photovoltaic arrays, the giant solar panels that provide most of the station’s power. I suppose that was similar to having house guests. Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev were the first to adapt to long-term life in low orbit, orbiting Earth approximately 15.5 times a day and exercising at least two hours daily to counteract muscle atrophy due to low gravity. You wouldn’t think that humans could lose muscle mass in space (or at least, I didn’t), but like with any other muscle strength, it really is a “use it or lose it” situation.

All in all, the three men were in space for a little over three months. It was a momentous event. Then, on March 10, the space shuttle Discovery brought three new residents to replace the Expedition 1 crew. Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev returned to Earth at the Kennedy Space Center on March 21. Since then, humans have

continuously lived on the ISS, with plans to extend the mission until at least 2030. To date, 236 individuals from 18 countries have visited the station, and several new modules have been added, many aimed at conducting biological research. Like Niel Armstrong said when he stepped on the surface of the moon in 1969, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Yes, it was…and so was this.

continuously lived on the ISS, with plans to extend the mission until at least 2030. To date, 236 individuals from 18 countries have visited the station, and several new modules have been added, many aimed at conducting biological research. Like Niel Armstrong said when he stepped on the surface of the moon in 1969, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Yes, it was…and so was this.

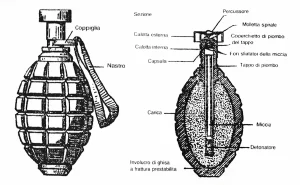

In what must be considered very unconventional, at least these days, Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti of the Italian army effectively dropped the first aerial bombs on November 1, 1911. He took four grenades (“Cipelli”) in a leather pouch, each of a size of grapefruit and weighing about four pounds. The bombing took place during a flight over Libya, when Gavotti threw three grenades from his aircraft onto a Turkish encampment. These days we wouldn’t have even considered that to be a bombing run, but…well, what else could it be called. Planes were very new, and bombing runs unheard of. It was just eight years after the Wright brothers achieved the world’s first flight in America, and the Kingdom of Italy dispatched several aircraft to Libya, aiming to seize territory in their conflict with the disintegrating Ottoman Empire. Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti boarded one of the Italian army’s wood-and-canvas “Taube” airplanes, carrying four grenades. It was a bold move, but then I’m quite sure that there were no anti-aircraft guns to worry about, and no fighter planes to run from either.

In what must be considered very unconventional, at least these days, Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti of the Italian army effectively dropped the first aerial bombs on November 1, 1911. He took four grenades (“Cipelli”) in a leather pouch, each of a size of grapefruit and weighing about four pounds. The bombing took place during a flight over Libya, when Gavotti threw three grenades from his aircraft onto a Turkish encampment. These days we wouldn’t have even considered that to be a bombing run, but…well, what else could it be called. Planes were very new, and bombing runs unheard of. It was just eight years after the Wright brothers achieved the world’s first flight in America, and the Kingdom of Italy dispatched several aircraft to Libya, aiming to seize territory in their conflict with the disintegrating Ottoman Empire. Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti boarded one of the Italian army’s wood-and-canvas “Taube” airplanes, carrying four grenades. It was a bold move, but then I’m quite sure that there were no anti-aircraft guns to worry about, and no fighter planes to run from either.

Gavotti headed towards the Turkish oasis encampment of Ain Zara, east of what is now Tripoli, and dropped

three of his four grenades. This event marked the first instance of live ordnance being released from an aircraft under enemy fire. The Ottoman Empire expressed indignation, alleging that the bombs had hit a field hospital and resulted in civilian casualties. Subsequent investigations by the governments of Great Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and the United States concluded that the bombing likely resulted in minimal, if any, casualties since the grenades either failed to detonate or landed in uninhabited desert areas. Nevertheless, the Ottoman Empire was looking to garner sympathy for the act, and in reality, it was the beginning of many civilian casualties that could later be attributed to the bombings of war.

three of his four grenades. This event marked the first instance of live ordnance being released from an aircraft under enemy fire. The Ottoman Empire expressed indignation, alleging that the bombs had hit a field hospital and resulted in civilian casualties. Subsequent investigations by the governments of Great Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and the United States concluded that the bombing likely resulted in minimal, if any, casualties since the grenades either failed to detonate or landed in uninhabited desert areas. Nevertheless, the Ottoman Empire was looking to garner sympathy for the act, and in reality, it was the beginning of many civilian casualties that could later be attributed to the bombings of war.

While that first “aerial bombing” brought with it limited collateral damage, it signified the beginning of a new era in aerial warfare, nevertheless. A Berlin newspaper observed that although airplanes and airships were not  practical for offensive purposes, they proved indispensable for reconnaissance, stating, “The Italian Command is always, thanks to aircraft, informed of every displacement of Turkish troops, and knows the exact positions of them.” In subsequent years, German Zeppelin airships during World War I carried out bombings over cities throughout Europe, from Antwerp to Paris to London, heralding a time when aircraft would target not just military personnel but also civilian populations. While the Zeppelin bombings were much more effective, the credit for the first aerial bombing goes to the Italians, and Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti. I wonder how shocked the people on the ground were when those grenades dropped.

practical for offensive purposes, they proved indispensable for reconnaissance, stating, “The Italian Command is always, thanks to aircraft, informed of every displacement of Turkish troops, and knows the exact positions of them.” In subsequent years, German Zeppelin airships during World War I carried out bombings over cities throughout Europe, from Antwerp to Paris to London, heralding a time when aircraft would target not just military personnel but also civilian populations. While the Zeppelin bombings were much more effective, the credit for the first aerial bombing goes to the Italians, and Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti. I wonder how shocked the people on the ground were when those grenades dropped.

Halloween in the United States traces its origins to the customs of European immigrants, especially those from Ireland and Scotland. The term “Halloween” is derived from “All Hallow’s Eve,” which is the night before the Christian sacred observances of All Hallow’s Day on November 1st and All Souls’ Day on November 2nd. Similar to other significant Christian dates, it included vigils starting the previous evening. This trio of days is known as Allhallowtide, a time when Christians pay homage to all saints and offer prayers for the souls that have passed away recently. People pray for the dead for several reasons…among them, hope for salvation (it was thought that prayers express hope that God will free the deceased from sin and prepare a place in heaven), coping with bereavement (it was thought that praying for the dead helps ordinary Christians deal with loss), charity and atonement (it was thought that we can do acts of charity for the departed to help atone for their sins)…or so they believe. I don’t personally believe that our prayers for the dead will do these things, but that was the tradition.

Halloween in the United States traces its origins to the customs of European immigrants, especially those from Ireland and Scotland. The term “Halloween” is derived from “All Hallow’s Eve,” which is the night before the Christian sacred observances of All Hallow’s Day on November 1st and All Souls’ Day on November 2nd. Similar to other significant Christian dates, it included vigils starting the previous evening. This trio of days is known as Allhallowtide, a time when Christians pay homage to all saints and offer prayers for the souls that have passed away recently. People pray for the dead for several reasons…among them, hope for salvation (it was thought that prayers express hope that God will free the deceased from sin and prepare a place in heaven), coping with bereavement (it was thought that praying for the dead helps ordinary Christians deal with loss), charity and atonement (it was thought that we can do acts of charity for the departed to help atone for their sins)…or so they believe. I don’t personally believe that our prayers for the dead will do these things, but that was the tradition.

Of course, there are other traditions that have come into being concerning Halloween. Some traditions take on  “the darker side” and some keep things purely secular, saying that Halloween is just a day of kids costumes and free candy. For the kids, it seems that while the costumes are cool, having a huge sack of candy, that will supposedly be under their complete control, is beyond the coolest of their imaginations. Of course, most parents won’t allow the child to have complete control of so much candy, but hey, a kid can dream.

“the darker side” and some keep things purely secular, saying that Halloween is just a day of kids costumes and free candy. For the kids, it seems that while the costumes are cool, having a huge sack of candy, that will supposedly be under their complete control, is beyond the coolest of their imaginations. Of course, most parents won’t allow the child to have complete control of so much candy, but hey, a kid can dream.

In colonial America, Halloween was not celebrated as it is today. The New England Puritans strongly opposed this holiday, along with many others. Some historians note that Anglican colonists in the southern United States and Catholic colonists in Maryland observed All Hallow’s Eve in their church calendars. Nevertheless, it did not become a significant holiday until the mass immigration of the Irish and Scots in the 19th century. The Irish and Scottish immigrants introduced customs like carving turnips, creating jack-o-lanterns, and igniting bonfires. These traditions merged with those of other communities in America. Initially, pumpkin carving in the United States was linked to harvest time, but eventually it became a Halloween staple. In Cajun regions, influenced by French culture, night masses were held, blessed candles were placed on graves, and families often spent the entire night beside their loved ones’ resting places.

Personally, I like the cute little costumes the little kids wear, and how excited they are when someone gives

them candy. I saw a commercial in which a boy tells his dad what he loves about Halloween…that people give him KitKats for free. It doesn’t faze the boy at all, when his dad tells him that he’s 8 and therefore all his KitKats are free. The boy isn’t concerned about that, he just keeps on talking about why he loves the day. However you celebrate, have a safe and happy Halloween.

them candy. I saw a commercial in which a boy tells his dad what he loves about Halloween…that people give him KitKats for free. It doesn’t faze the boy at all, when his dad tells him that he’s 8 and therefore all his KitKats are free. The boy isn’t concerned about that, he just keeps on talking about why he loves the day. However you celebrate, have a safe and happy Halloween.

Have you ever wondered how a city got its start and its name? For one small frontier town in Kansas Territory, United States, it all began on October 29, 1858, when the first store opened. The store was probably situated near the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek, the present-day location of central Denver. This junction of rivers also served as a cultural crossroads between the Southern Arapaho and white settlers pursuing gold rumors. One short month later the small frontier town would take on the name of Denver in a shameless ploy to curry favor with Kansas Territorial Governor James W Denver.

Have you ever wondered how a city got its start and its name? For one small frontier town in Kansas Territory, United States, it all began on October 29, 1858, when the first store opened. The store was probably situated near the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek, the present-day location of central Denver. This junction of rivers also served as a cultural crossroads between the Southern Arapaho and white settlers pursuing gold rumors. One short month later the small frontier town would take on the name of Denver in a shameless ploy to curry favor with Kansas Territorial Governor James W Denver.

Denver was conceived by a town promoter and real estate salesman from Kansas named William H Larimer Jr, and that first store was established to cater to miners extracting placer gold found a year earlier at the confluence of Cherry Creek and the South Platte River. Many small frontier towns have simply become ghost towns now, but that was not to be the case for Denver. By 1859, the area had seen an influx of tens of thousands of gold seekers. Still, it’s existence would not be without struggle. The placer deposits were  diminishing, prompting most miners to either return home or venture westward into the mountains in pursuit of the more abundant veins.

diminishing, prompting most miners to either return home or venture westward into the mountains in pursuit of the more abundant veins.

By 1860, Larimer’s fledgling town was on the brink of failure. Despite its central location for servicing mining camps along the Rocky Mountain Front Range, Denver lacked the necessary rail and water transportation routes for affordable goods delivery. The transcontinental Union Pacific Railroad, launched in 1869, initially bypassed Denver. However, in 1870, Denver started to break free from its geographical isolation when the Kansas Pacific Railroad arrived from the east and the 105-mile Denver Pacific Railway connected Denver to the Union Pacific line at Cheyenne. Subsequent rail lines linked Denver with the flourishing mining areas in the Rockies, and by the mid-1870s, Denver was prospering as a railroad hub and a focal point of the western mining industry. The railroads had saved the town.

By 1890, Denver’s population exceeded 106,000, ranking it as the 26th largest urban area in the United States and giving it the moniker “Queen City of the Plains.” The Silver Panic of 1893 abruptly halted the economic

boom, which was only partially revived by the 1894 gold discoveries at Cripple Creek. So, there was still some concern about the viability of the city. The increasing importance of farming and ranching helped stabilize the city’s economy by reducing reliance on mining and quite possibly saving the city. Still, the cyclical nature of economic booms and busts continues as a dominant force in Denver, as well as in many other western cities, for much of the 20th century.

boom, which was only partially revived by the 1894 gold discoveries at Cripple Creek. So, there was still some concern about the viability of the city. The increasing importance of farming and ranching helped stabilize the city’s economy by reducing reliance on mining and quite possibly saving the city. Still, the cyclical nature of economic booms and busts continues as a dominant force in Denver, as well as in many other western cities, for much of the 20th century.

On October 24, 1945, the United Nations Charter, adopted and signed on June 26, 1945, came into effect. The United Nations (UN) emerged from a “perceived” need for a mechanism superior to the League of Nations in arbitrating international conflicts and negotiating peace. The escalating Second World War prompted the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union to draft the initial UN Declaration, which 26 nations signed in January 1942 as an official stance against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan. It all seemed like a good idea, and perhaps was drafted with good intentions, but it is my opinion that the UN has failed miserably to accomplish any of the goals it set out to achieve.

On October 24, 1945, the United Nations Charter, adopted and signed on June 26, 1945, came into effect. The United Nations (UN) emerged from a “perceived” need for a mechanism superior to the League of Nations in arbitrating international conflicts and negotiating peace. The escalating Second World War prompted the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union to draft the initial UN Declaration, which 26 nations signed in January 1942 as an official stance against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan. It all seemed like a good idea, and perhaps was drafted with good intentions, but it is my opinion that the UN has failed miserably to accomplish any of the goals it set out to achieve.

The foundational principles of the UN Charter were initially shaped during the San Francisco Conference, which began on April 25, 1945. This conference established the framework for a new international organization intended to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.” The Charter further outlined two additional vital goals. They were to maintain the principles of equal rights and self-determination for all peoples…initially intended to safeguard smaller nations at risk of being overtaken by the larger Communist powers emerging after the war, and to promote international collaboration to tackle worldwide economic, social, cultural, and humanitarian issues.

Following the war’s end, the responsibility of negotiating and maintaining peace was assigned to the newly established UN Security Council, which included the United States, Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and China. Each member possessed veto power. Winston Churchill implored the United Nations to employ its charter to promote a new, united Europe…a unity characterized by its opposition to communist expansion in both the East and the West. Yet, given the composition of the Security Council, achieving this proved more challenging than anticipated. I suppose that the distain felt by many people, for the United Nations, could have arisen from an impossible task, but more likely it came from flawed people who placed their own agenda ahead of the real needs of the people.

The United Nations is subject to criticism for a variety of reasons, including its policies, ideology, equality of representation, administrative practices, enforcement of decisions, and perceived ideological biases. Critics often cite a lack of success within the organization, noting failures in both preventative measures and in de-escalating conflicts ranging from social disputes to full-blown wars. Additional criticisms involve accusations of antisemitism, appeasement, collusion, promotion of globalism, inaction, and the exertion of undue influence by

powerful nations within the General Assembly, as well as corruption and misallocation of resources. In my opinion, and that of many other people, that the UN should be dissolved, or at the very least, that the United States should withdraw and expel the United Nations from this nation. While some may disagree, this is my viewpoint.

powerful nations within the General Assembly, as well as corruption and misallocation of resources. In my opinion, and that of many other people, that the UN should be dissolved, or at the very least, that the United States should withdraw and expel the United Nations from this nation. While some may disagree, this is my viewpoint.

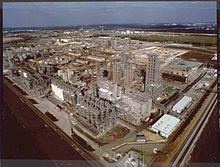

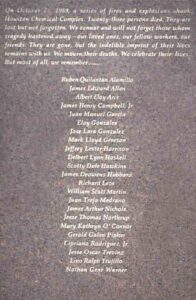

There is really no good reason to ever compromise on the safety procedures in a plant. People often think that it’s not that important to follow every safety procedure, every time…until something goes wrong. Then, they know the purpose of the safety procedures. On October 23, 1989, 23 people lost their lives in a series of explosions sparked by an ethylene leak at a factory in Pasadena, Texas. It was determined that the blasts, which took place at a Phillips Petroleum Company plant, were caused by inadequate safety procedures.

There is really no good reason to ever compromise on the safety procedures in a plant. People often think that it’s not that important to follow every safety procedure, every time…until something goes wrong. Then, they know the purpose of the safety procedures. On October 23, 1989, 23 people lost their lives in a series of explosions sparked by an ethylene leak at a factory in Pasadena, Texas. It was determined that the blasts, which took place at a Phillips Petroleum Company plant, were caused by inadequate safety procedures.

The Phillips 66 Chemical Complex in Pasadena houses a polyethylene reactor that synthesizes essential chemical compounds for plastic production. This facility generates millions of pounds of plastic each day, which are then utilized in manufacturing toys and various containers. Always looking to better their bottom line, Phillips outsourced a significant portion of the plant’s essential maintenance work to reduce expenses. Fish Engineering and Construction, the main subcontractor, already had a less-than-exemplary reputation before the disaster on  October 23rd. Previously, in August, a Fish worker-initiated maintenance on gas piping without isolating it, leading to the release of flammable solvents and gas into a work area. The resulting ignition caused the death of one employee and injuries to four others.

October 23rd. Previously, in August, a Fish worker-initiated maintenance on gas piping without isolating it, leading to the release of flammable solvents and gas into a work area. The resulting ignition caused the death of one employee and injuries to four others.

Then, at 1:05pm, on October 23rd, during maintenance work on the plant’s polyethylene reactor, issues emerged once more. A valve was improperly secured, leading to the release of 85,000 pounds of highly flammable ethylene-isobutane gas into the plant around 1pm. The absence of detectors or warning systems failed to alert anyone of the looming catastrophe. In under two minutes, the vast gas cloud exploded with the force equivalent to two-and-a-half tons of dynamite. The blast was heard for miles in every direction, and the ensuing fireball could be seen from at least 15 miles away. At Phillips, twenty-three workers lost their lives and an additional 130 sustained serious injuries when the initial explosion triggered a series of subsequent explosions.

The initial emergency response came from the Phillips Petroleum Company’s fire brigade, who were quickly supported by the Channel Industries Mutual Aid (CIMA) team. Collaborating governmental entities included the Texas Air Control Board, Harris County Pollution Control, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the US Coast Guard, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The initial emergency response came from the Phillips Petroleum Company’s fire brigade, who were quickly supported by the Channel Industries Mutual Aid (CIMA) team. Collaborating governmental entities included the Texas Air Control Board, Harris County Pollution Control, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the US Coast Guard, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Investigation of the disaster revealed that despite the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) citing Phillips for multiple serious safety violations in the past, a comprehensive inspection of the plant had not been conducted since 1975. Testimonies also uncovered that the plant was susceptible to disaster due to insufficient safety measures during maintenance. Nevertheless, even knowing all that, Phillips and its managers were never required to face criminal charges.

Each American presidency is marked by a defining moment, an event that encapsulates its tenure. For John F. Kennedy’s presidency, the Cuban Missile Crisis stood as that pivotal event. The most intense phase of the crisis, often referred to as the “13 Days,” spanned from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy was informed of the Soviet missile sites being built in Cuba, to October 28, 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev declared the dismantling of the missiles. On October 22, 1962, when it came time to tell the American people about the situation, President Kennedy revealed in a televised address of profound significance, that American spy planes had detected Soviet missile bases in Cuba. This represented a very dangerous situation for the United States. The missile sites were still under construction, but they were close to completion, and they contained medium-range missiles with the capacity to hit several major US cities, including Washington DC.

Each American presidency is marked by a defining moment, an event that encapsulates its tenure. For John F. Kennedy’s presidency, the Cuban Missile Crisis stood as that pivotal event. The most intense phase of the crisis, often referred to as the “13 Days,” spanned from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy was informed of the Soviet missile sites being built in Cuba, to October 28, 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev declared the dismantling of the missiles. On October 22, 1962, when it came time to tell the American people about the situation, President Kennedy revealed in a televised address of profound significance, that American spy planes had detected Soviet missile bases in Cuba. This represented a very dangerous situation for the United States. The missile sites were still under construction, but they were close to completion, and they contained medium-range missiles with the capacity to hit several major US cities, including Washington DC.

Kennedy declared he was imposing a naval “quarantine” on Cuba to block Soviet ships from delivering additional offensive weapons to the island. He stated that the United States would not accept the current missile sites’ presence. The president emphasized that America was prepared to take military action to eliminate what he described as a “secretive, irresponsible, and provocative threat to global peace.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis, as it became known, began on October 14, 1962, when US intelligence, analyzing data from a U-2 spy plane, discovered that the Soviet Union was constructing medium-range missile sites in Cuba. The following day, President Kennedy convened a secret emergency meeting with his top military, political, and diplomatic advisers to address the grave situation. This group came to be known as ExComm, an abbreviation for Executive Committee. Opting against a surgical air strike on the missile sites, ExComm instead chose a naval blockade and demanded the dismantling and removal of the missiles. It was then, on the evening of October 22, that President Kennedy disclosed his decision on national television. Tensions continued to mount over the ensuing six days, to a critical point, and placing the world on the edge of nuclear warfare between the two superpowers.

On October 23, the United States initiated a naval “quarantine” of Cuba. However, President Kennedy opted to allow Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev additional time to contemplate the US maneuver by moving the quarantine line back 500 miles. By October 24, Soviet vessels bound for Cuba, capable of transporting military cargo, seemed to have decelerated, changed course, or turned around as they neared the quarantine zone, except for one ship…the tanker Bucharest. Following appeals from over 40 nonaligned countries, UN Secretary-General U Thant made private overtures to Kennedy and Khrushchev, imploring their administrations to “avoid any actions that might worsen the situation and pose a risk of war.” Under orders from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, United States armed forces escalated to DEFCON 2, the most critical military readiness level ever achieved in the postwar period, while commanders readied for an all-out conflict with the Soviet Union.

On October 25, the aircraft carrier USS Essex and the destroyer USS Gearing tried to intercept the Soviet tanker Bucharest as it breached the US quarantine of Cuba. The Soviet vessel did not comply, but the US Navy refrained from taking it by force, judging that it was unlikely to be carrying offensive weapons. On October 26, Kennedy was informed that construction on the missile bases continued unabated, and ExComm contemplated a US invasion of Cuba. The Soviets apparently felt the tension of their actions, because on that same day, they offered a deal to resolve the crisis: they would dismantle the missile bases in return for a United States guarantee not to invade Cuba.

The following day, Khrushchev escalated the situation by publicly demanding the removal of US missile bases in Turkey, influenced by Soviet military leaders. As Kennedy and his advisors deliberated over this perilous shift in negotiations, a U-2 spy plane was downed over Cuba, resulting in the death of its pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson. It looked like thing might have reached the boiling point, but despite the Pentagon’s dismay, Kennedy prohibited any military response unless further surveillance aircraft were targeted over Cuba. To alleviate the intensifying crisis, Kennedy and his team decided to dismantle the US missile installations in Turkey at a subsequent time, to avoid provoking Turkey, who was an essential NATO ally.

On October 28, Khrushchev declared his government’s decision to dismantle and remove all offensive Soviet weapons from Cuba. Following the broadcast of this public announcement on Radio Moscow, the USSR affirmed its readiness to adopt the resolution secretly suggested by the Americans the previous day. That afternoon, Soviet technicians started dismantling the missile sites, averting the imminent threat of nuclear war. The Cuban Missile Crisis had effectively ended. In November, Kennedy lifted the blockade, and by year’s end, all offensive missiles were removed from Cuba. Later, the United States discreetly withdrew its missiles from Turkey.

At the time, the Cuban Missile Crisis appeared to be a definitive triumph for the United States. In this, Cuba gained a heightened sense of security following the crisis. The withdrawal of obsolete Jupiter missiles from Turkey did not negatively impact the United States’ nuclear strategy. Nevertheless, the crisis spurred the USSR, feeling humiliated, to initiate a substantial nuclear arms expansion. By the 1970s, the Soviet Union had achieved nuclear parity with the United States and developed intercontinental ballistic missiles with the capability to target any city within the United States.

The presidents that followed Kennedy upheld his promise to refrain from invading Cuba, and the relationship with the communist nation, located a mere 80 miles off the coast of Florida, continued to challenge United States foreign policy for over half a century. Finally, in 2015, representatives from both countries declared the official normalization of United States-Cuba relations, encompassing the relaxation of travel bans and the establishment of embassies and diplomatic offices in each nation.

For Kennedy, this pivotal moment in his administration showcased his ability to manage a high-stakes international crisis. His decision to implement a naval blockade and negotiate with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev helped avoid a potential nuclear war. It also demonstrated his leadership and diplomatic skills, as he balanced military readiness with diplomatic negotiations, which ultimately led to the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba. The successful resolution of the crisis significantly boosted Kennedy’s public image, portraying him as a strong and capable leader who could protect the United States from external threats. The crisis was a defining moment in the Cold War, highlighting the intense rivalry between the United States and the

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it also led to the establishment of a direct communication line between Washington and Moscow, known as the “hotline,” to prevent future crises. In summary, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a defining event that not only tested Kennedy’s presidency, but it also shaped his legacy as a leader who could navigate the complexities of international relations during one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War.

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it also led to the establishment of a direct communication line between Washington and Moscow, known as the “hotline,” to prevent future crises. In summary, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a defining event that not only tested Kennedy’s presidency, but it also shaped his legacy as a leader who could navigate the complexities of international relations during one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War.

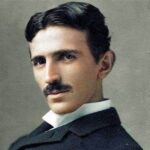

Sometimes, in the minds of geniuses, ideas can become lost or even stolen when the genius lacks the patience to promote their inventions to the world. They have innovated minds, but the marketing, patents, and mass-producing part is boring to them. Nikola Tesla, who was born on July 10, 1856, was such a scientist. Tesla was of Serbian nationality in Smiljan, within the Austrian Empire. He was considered one of the greatest and most enigmatic contributors to the development of electromagnetism and various scientific advancements of his era. Despite his impressive array of patents and discoveries, his contributions were frequently overshadowed during his life.

Sometimes, in the minds of geniuses, ideas can become lost or even stolen when the genius lacks the patience to promote their inventions to the world. They have innovated minds, but the marketing, patents, and mass-producing part is boring to them. Nikola Tesla, who was born on July 10, 1856, was such a scientist. Tesla was of Serbian nationality in Smiljan, within the Austrian Empire. He was considered one of the greatest and most enigmatic contributors to the development of electromagnetism and various scientific advancements of his era. Despite his impressive array of patents and discoveries, his contributions were frequently overshadowed during his life.

Nikola Tesla, a gifted student, attended the Austrian Polytechnic in Graz in 1875. He later moved to secure a job in Marburg, Slovenia. His challenging disposition occasionally surfaced, leading to a falling out with his family and a subsequent nervous breakdown. It is said that Tesla had an IQ of somewhere between 160 and 310 or “off the charts.” That makes it entirely possible that Tesla suffered with many mood swings. After leaving Slovenia, he registered at Charles Ferdinand University in Prague, only to leave once more without finishing his degree.

In his early years, he went through numerous bouts of sickness and bursts of striking inspiration. He frequently had visions of mechanical and theoretical inventions, often accompanied by intense flashes of light. His ability to visualize images in his mind was extraordinary. Instead of drafting plans or scale drawings for his projects, he depended on the vivid images in his imagination.

In 1880, he relocated to Budapest to work for a telegraph company. It was there that he familiarized himself  with twin turbines and contributed to the development of a device that amplified telephone signals. In 1882, he transferred to Paris to join the Continental Edison Company. During his tenure, he enhanced several Edison devices and devised the induction motor and other apparatuses utilizing rotating magnetic fields. Then, armed with a strong recommendation letter, Tesla arrived in the United States in 1884 to join the Edison Machine Works. There, he quickly rose to become a chief engineer and designer. Tasked with enhancing the direct current generators’ electrical system, Tesla was allegedly promised $50,000 for significant improvements. Despite fulfilling his task, Tesla was apparently not compensated, fueling a profound rivalry and resentment towards Thomas Edison. This animosity became a hallmark of Tesla’s life, affecting his financial standing and reputation. The intense feud is also cited as a contributing factor to why neither Tesla nor Edison received the Nobel Prize for their contributions to electrical engineering.

with twin turbines and contributed to the development of a device that amplified telephone signals. In 1882, he transferred to Paris to join the Continental Edison Company. During his tenure, he enhanced several Edison devices and devised the induction motor and other apparatuses utilizing rotating magnetic fields. Then, armed with a strong recommendation letter, Tesla arrived in the United States in 1884 to join the Edison Machine Works. There, he quickly rose to become a chief engineer and designer. Tasked with enhancing the direct current generators’ electrical system, Tesla was allegedly promised $50,000 for significant improvements. Despite fulfilling his task, Tesla was apparently not compensated, fueling a profound rivalry and resentment towards Thomas Edison. This animosity became a hallmark of Tesla’s life, affecting his financial standing and reputation. The intense feud is also cited as a contributing factor to why neither Tesla nor Edison received the Nobel Prize for their contributions to electrical engineering.

Disappointed by the lack of a pay raise, Tesla resigned and briefly worked digging ditches for the Edison telephone company. In 1886, he established his own company, which failed due to his investors’ lack of faith in alternating current (AC). The following year, Tesla experimented with a type of X-Ray technology, managing to photograph the bones in his hand and recognizing the harmful side-effects of radiation. Despite this, his work received minimal attention, and much of his research was destroyed in a fire at a New York warehouse.

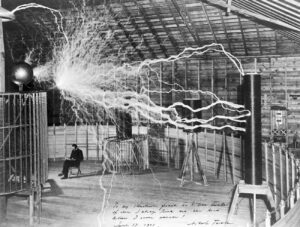

Nikola Tesla was renowned for his intense work ethic and dedication to his work. He often dined alone and  seldom slept, sometimes only two hours per day. He never married, believing that his celibacy was beneficial to his scientific pursuits. In his later years, he adopted a vegetarian diet, subsisting solely on milk, bread, honey, and vegetable juices. In his lifetime, Tesla can be credited with many inventions, among them, the Tesla coil: A system for wireless transmission of electricity; the Tesla turbine: A type of turbine; the radio: Tesla demonstrated radio communication before Marconi; the Magnifying transmitter: A device for wireless energy transmission; and the Induction motor: A key component in modern devices. Tesla died on January 7, 1943, in a hotel room in New York City at the age of 86. After his death, in 1960 the General Conference on Weights and Measures named the SI unit of magnetic field strength the Tesla in his honor.

seldom slept, sometimes only two hours per day. He never married, believing that his celibacy was beneficial to his scientific pursuits. In his later years, he adopted a vegetarian diet, subsisting solely on milk, bread, honey, and vegetable juices. In his lifetime, Tesla can be credited with many inventions, among them, the Tesla coil: A system for wireless transmission of electricity; the Tesla turbine: A type of turbine; the radio: Tesla demonstrated radio communication before Marconi; the Magnifying transmitter: A device for wireless energy transmission; and the Induction motor: A key component in modern devices. Tesla died on January 7, 1943, in a hotel room in New York City at the age of 86. After his death, in 1960 the General Conference on Weights and Measures named the SI unit of magnetic field strength the Tesla in his honor.