History

Walter Hunt was a mechanic and independent inventor from New York. That basically meant he dabbled at inventions, but in this case, while he may not have realized the value of his invention, he would go on to invent on of the most important and versatile tools there is. The sad thing for Hunt is that because he didn’t realize what he had, he sold his patent for far less than its value. On April 10, 1849, Hunt sold the patent for his safety pin, unique with its metal loop that created a spring for just $400 ($16,502 today). While $16,502 sounds like a lot of money, the purchaser would go on to make millions off of Hunt’s invention. Hunt would never receive another penny.

Walter Hunt was a mechanic and independent inventor from New York. That basically meant he dabbled at inventions, but in this case, while he may not have realized the value of his invention, he would go on to invent on of the most important and versatile tools there is. The sad thing for Hunt is that because he didn’t realize what he had, he sold his patent for far less than its value. On April 10, 1849, Hunt sold the patent for his safety pin, unique with its metal loop that created a spring for just $400 ($16,502 today). While $16,502 sounds like a lot of money, the purchaser would go on to make millions off of Hunt’s invention. Hunt would never receive another penny.

Hunt was born on July 29, 1796, in Martinsburg, New York. Because he had a debt of $25 that he needed to pay, he scrambled to invent something that would earn him some money. Playing with a piece of metal wire, he twisted and turned it into what he called a “dress pin,” which had a spring at one end that forced the other end into a clasp. The invention wasn’t completely new, since ancient Romans used something similar for jewelry, but rather it was simply an improvement of the original design. Another version of a safety pin came out in 1842, but it had no spring, unlike the pins we know today. Hunt decided to patent his invention, and it was given US Patent Number 6,281. Today, many years later, Hunt’s design still has countless everyday uses, including fastening clothing and diapers. At one time a large version was used to adorn the outside of a wrap-around skirt.

The safety pin wasn’t his greatest invention, nor the one which brought him the most money, but it has

changed the lives of countless numbers of people to this day. In his lifetime, Hunt achieved moderate success and invented many items, including a repeating rifle, a flax spinner, a fountain pen, a knife sharpener, an ice plough, and one of the world’s first sewing machines with an eye-pointed needle. Hunt’s sewing machine actually triggered a patent dispute with another inventor, Elias Howe. He died of pneumonia at his place of business in New York City on June 8, 1859. He was 62 years old.

changed the lives of countless numbers of people to this day. In his lifetime, Hunt achieved moderate success and invented many items, including a repeating rifle, a flax spinner, a fountain pen, a knife sharpener, an ice plough, and one of the world’s first sewing machines with an eye-pointed needle. Hunt’s sewing machine actually triggered a patent dispute with another inventor, Elias Howe. He died of pneumonia at his place of business in New York City on June 8, 1859. He was 62 years old.

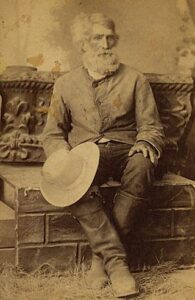

Samuel Langhorne Clemens alias Mark Twain had a number of jobs before he became a famous writer. Clemens childhood was a difficult one, beginning with his premature birth on November 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri. He was the sixth of seven children born to John Marshall Clemens and Jane Lampton Clemens. Only three of those children would survive to adulthood. Clemens, himself was sickly and frail until he was 7 years old. In 1839 the family moved to the town of Hannibal, Missouri. His popular novels “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” were set in a fictionalized version of Hannibal. John Marshall Clemens became a justice of the peace in Hannibal but struggled financially. Samuel Clemens was just 11 years old when his 49-year-old father died of pneumonia. Clemens’ life was about to change forever.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens alias Mark Twain had a number of jobs before he became a famous writer. Clemens childhood was a difficult one, beginning with his premature birth on November 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri. He was the sixth of seven children born to John Marshall Clemens and Jane Lampton Clemens. Only three of those children would survive to adulthood. Clemens, himself was sickly and frail until he was 7 years old. In 1839 the family moved to the town of Hannibal, Missouri. His popular novels “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” were set in a fictionalized version of Hannibal. John Marshall Clemens became a justice of the peace in Hannibal but struggled financially. Samuel Clemens was just 11 years old when his 49-year-old father died of pneumonia. Clemens’ life was about to change forever.

In 1848, the year after his father’s death, Clemens went to work full-time as an apprentice printer at a newspaper in Hannibal. Remember that he was just a boy of 12 years at the time. In 1851, he moved over to a typesetting job at a local paper owned by his older brother, Orion. This would have been a promotion of sorts, but it also sparked something in him that would eventually make him the man what the world would know. He began to write a handful of short stories, and so began his lifelong writing career, although not on that exact day. He would have to do a few other things first. Nevertheless, some of his stories were published. In 1853, when he was 17 years old, Clemens left Hannibal and spent the next several years living in places such as New York City, Philadelphia and Keokuk, Iowa, and working as a printer.

In 1857, he decided to try something new, and signed on as a pilot’s apprentice on a river boat while on his way to Mississippi. He had been commissioned to write a series of comic travel letters for the Keokuk Daily Post, but after writing five, decided he’d rather be a pilot than a writer. this decision would also lead to a tragedy when, in 1858, while employed on a boat called the Pennsylvania, he got his younger brother, Henry, a job aboard the vessel. He worked on the Pennsylvania until early June. Then, on June 13, disaster struck when  the Pennsylvania, traveling near Memphis, experienced a deadly boiler explosion. Among the dead was 19-year-old Henry. Nevertheless, Clemens continued to work as a pilot’s apprentice and on April 9, 1859, a 23-year-old Clemens received his steamboat pilot’s license. He piloted his own boats for two years, until the Civil War halted steamboat traffic. During his time as a pilot, he picked up the pseudonym “Mark Twain” from a boatman’s call noting that the river was only two fathoms deep, the minimum depth for safe navigation, hence Twain. When he returned to writing in 1861, working for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, he wrote a humorous travel letter signed by “Mark Twain” and continued to use the pseudonym for nearly 50 years.

the Pennsylvania, traveling near Memphis, experienced a deadly boiler explosion. Among the dead was 19-year-old Henry. Nevertheless, Clemens continued to work as a pilot’s apprentice and on April 9, 1859, a 23-year-old Clemens received his steamboat pilot’s license. He piloted his own boats for two years, until the Civil War halted steamboat traffic. During his time as a pilot, he picked up the pseudonym “Mark Twain” from a boatman’s call noting that the river was only two fathoms deep, the minimum depth for safe navigation, hence Twain. When he returned to writing in 1861, working for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, he wrote a humorous travel letter signed by “Mark Twain” and continued to use the pseudonym for nearly 50 years.

He moved to San Francisco in 1864, to work as a reporter. While there, he wrote the story that made him famous, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” He traveled to Hawaii as a correspondent for the Sacramento Union in 1866. After his stint in Hawaii, he traveled the world writing accounts for papers in California and New York, which he later published as the popular book The Innocents Abroad in 1869. In 1870, when he was 35 years old, Clemens married Olivia Langdon, who was the daughter of a wealthy New York coal merchant and settled in Hartford, Connecticut, where he continued to write travel accounts and lecture. In 1875, his novel “Tom Sawyer” was published, followed by “Life on the Mississippi” in 1883, and his masterpiece “Huckleberry Finn” in 1885. Some bad investments left the Clemens family bankrupt after the publication of Huckleberry Finn, but he won back his financial standing with his next three books. He and Olivia had four children, their son Langdon died of diphtheria in 1872 at the age of 19 months. They also had three daughters: Susy (1872–1896), Clara (1874–1962), and Jean (1880–1909). Clara Clemens had one child, Nina Gabrilowitsch, who passed away in 1966, leaving no direct descendants of Samuel Clemens “Mark Twain.” Clemens and his family moved to Italy in 1903. Sadly, his wife died on June 5, 1904. Her death left him sad and bitter, and his work, while still humorous, grew distinctly darker. Clemens “Mark Twain” died in 1910. As he

had predicted, or more likely chosen, “Mark Twain” died of a heart attack on April 21, 1910, at Stormfield, the mansion he had built in Redding, Connecticut…one day after Halley’s Comet was at its closest to the Sun and a month before the comet the passed near the Earth. I believe he was tired of living. He missed his wife, and most of his children had predeceased him. He was done, and simply ready to go home.

had predicted, or more likely chosen, “Mark Twain” died of a heart attack on April 21, 1910, at Stormfield, the mansion he had built in Redding, Connecticut…one day after Halley’s Comet was at its closest to the Sun and a month before the comet the passed near the Earth. I believe he was tired of living. He missed his wife, and most of his children had predeceased him. He was done, and simply ready to go home.

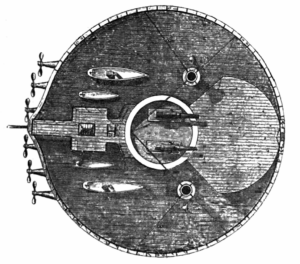

The Russian ship, Novgorod was a “monitor” built for the Imperial Russian Navy in the 1870s. A monitor is “a relatively small warship that is neither fast nor strongly armored but carries disproportionately large guns.” These ships were used by various navies from the 1860s, during the First World War and also has a limited presence in the Second World War. Novgorod was one of the most unusual warships ever constructed, and it is still considered in “popular naval myth” as one of the worst warships ever built. Whether it was a good warship or not, it certainly was one of the funniest looking warships of all time.

The Russian ship, Novgorod was a “monitor” built for the Imperial Russian Navy in the 1870s. A monitor is “a relatively small warship that is neither fast nor strongly armored but carries disproportionately large guns.” These ships were used by various navies from the 1860s, during the First World War and also has a limited presence in the Second World War. Novgorod was one of the most unusual warships ever constructed, and it is still considered in “popular naval myth” as one of the worst warships ever built. Whether it was a good warship or not, it certainly was one of the funniest looking warships of all time.

While funny looking, Novgorod was relatively effective in her designed role as a coast-defense ship, and apparently there were reasons for the design of the ship. The hull was circular to reduce draught (In maritime terms, “draught” (also spelled “draft”) refers to the vertical distance between the waterline and the bottom of a ship’s hull (keel)123. It is a critical measurement that indicates how deep a vessel sits in the water.) Well, this ship definitely sat low in the water, so I guess “draught” was reduced with this funny looking ship. The design allowed the ship to carry much more armor and a heavier armament than other ships of the same size. While she was funny looking, Novgorod played a minor role in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and was reclassified as a coast-defense ironclad in 1892.

Scottish shipbuilder John Elder published an article in 1868, that indicated that widening the beam of a ship would reduce the area that needed to be protected and allow it to carry thicker armor and heavier, more powerful guns in comparison to a ship with a narrower beam, as was the typical practice of the day. I suppose that makes sense. The low riding craft might also be somewhat more difficult to see in battle. In addition, only a moderate increase in power would be required to match the speed of a normal ship. according to Elder. Then Director of Naval Construction of the Royal Navy, Sir Edward Reed, agreed with Elder’s conclusions. Rear-Admiral Andrei Alexandrovich Popov of the Imperial Russian Navy decided that to further expand on Elder’s concept by broadening the ship, and in the end, it was actually circular and flat-bottomed, unlike Elder’s convex hull, to further minimize its draught. Thus, the funny looking monitor (also known as a popovkas) was born.

In his book, The World’s Worst Warships, naval historian Antony Preston characterized the popovkas like this: “But in other respects, they were a dismal failure. They were too slow to stem the current in the Dniepr, and proved very difficult to steer. In practice the discharge of even one gun caused them to turn out of control and

even contra-rotating some of six propellers was unable to keep the ship on the correct heading. Nor could they cope with the rough weather which is frequently encountered in the Black Sea. They were prone to rapid rolling and pitching in anything more than a flat calm and could not aim or load their guns under such circumstances.” The Novgorod popovkas ship was decommissioned in 1903 and used as a storeship until she was sold for scrap in 1911.

even contra-rotating some of six propellers was unable to keep the ship on the correct heading. Nor could they cope with the rough weather which is frequently encountered in the Black Sea. They were prone to rapid rolling and pitching in anything more than a flat calm and could not aim or load their guns under such circumstances.” The Novgorod popovkas ship was decommissioned in 1903 and used as a storeship until she was sold for scrap in 1911.

Funny thing…some things that used to be considered medicines years ago, have become common things today, like some condiments. Ketchup, for example, was sold in the 1830s as medicine. Apparently, an Ohio physician named John Cook Bennett, sold ketchup as a cure for upset stomach in 1834. Now, as a person who hates ketchup, I can say that it would have given me an upset stomach, but I am in the minority, I guess. It apparently took until the late 19th century for people to realize that while it didn’t help their upset stomach, they liked it on their food. wasn’t popularized as a condiment until the late 19th century! Apparently, Bennett sold the mix as a cure all for a number of things…including diarrhea, indigestion, and rheumatism. While it might have been a novel idea, it wasn’t based on fact.

Funny thing…some things that used to be considered medicines years ago, have become common things today, like some condiments. Ketchup, for example, was sold in the 1830s as medicine. Apparently, an Ohio physician named John Cook Bennett, sold ketchup as a cure for upset stomach in 1834. Now, as a person who hates ketchup, I can say that it would have given me an upset stomach, but I am in the minority, I guess. It apparently took until the late 19th century for people to realize that while it didn’t help their upset stomach, they liked it on their food. wasn’t popularized as a condiment until the late 19th century! Apparently, Bennett sold the mix as a cure all for a number of things…including diarrhea, indigestion, and rheumatism. While it might have been a novel idea, it wasn’t based on fact.

A mustard plaster, or mustard pack, is a home remedy believed to ease symptoms of respiratory conditions.  However, there’s no evidence that mustard plasters work. The treatment may also cause unwanted side effects such as skin irritation and burns. A mustard plaster is mainly used for coughing and congestion, but it’s also used for pain such as: backaches, cramps, and arthritis.

However, there’s no evidence that mustard plasters work. The treatment may also cause unwanted side effects such as skin irritation and burns. A mustard plaster is mainly used for coughing and congestion, but it’s also used for pain such as: backaches, cramps, and arthritis.

Apple cider vinegar (ACV) is a type of vinegar made with crushed fermented apples, yeast, and sugar. Vinegar is used in things like salad dressings, pickles, and marinades. While these food used are one thing, vinegar has also been used it as a home remedy…and still is today. Things like fighting germs to preventing heartburn. Recent studies had shown that it might have some real health benefits. Things like reducing blood sugar levels and aiding weight loss have been explored. As with other “condiment medicines” no real evidence of these benefits has been found. The good news is that ACV is harmless, if used correctly.  Vinegar does contain contains some of the nutrients in apple juice, including B vitamins and antioxidants called polyphenols, which is a good thing.

Vinegar does contain contains some of the nutrients in apple juice, including B vitamins and antioxidants called polyphenols, which is a good thing.

I suppose it could be said that these and other condiments contain vitamins, minerals, and other things that might be good for us, there is no proof that they are a substitute for medicines. The addition of sugar as an ingredient in modern recipes makes me question the nutritional value of these items, much less the medicinal value of them. Nevertheless, there are lots of medicines that don’t really help either and some that are actually detrimental to health, so that fact might need to be taken into account when we consider whether to go with natural medicine or man-made medicine.

It has long been known that the mineral hot springs waters can have a healing effect on the body. The heat opens the pores, and the minerals are absorbed through the skin to bring their healing effects. The Indians knew about the value of the waters in Thermopolis, Wyoming. As for the “white man’s” discovery of the healing waters, they were discovered by a man named John Colter in 1807 – 1808 during his winter exploration of the area. To the Shoshone Indian Tribe, who owned the land at that time, the area was known to the local Native American tribes as “Bah-gue-wana” or “smoking waters.” The town of Thermopolis itself got its name from the Greek words “thermo” (hot) and “polis” (city). History doesn’t record the exact conversation that led to the naming of Thermopolis, but it is said to have involved whiskey, outlaws, and a cowboy with a thick Irish brogue who convinced the townspeople it was the perfect name.

It has long been known that the mineral hot springs waters can have a healing effect on the body. The heat opens the pores, and the minerals are absorbed through the skin to bring their healing effects. The Indians knew about the value of the waters in Thermopolis, Wyoming. As for the “white man’s” discovery of the healing waters, they were discovered by a man named John Colter in 1807 – 1808 during his winter exploration of the area. To the Shoshone Indian Tribe, who owned the land at that time, the area was known to the local Native American tribes as “Bah-gue-wana” or “smoking waters.” The town of Thermopolis itself got its name from the Greek words “thermo” (hot) and “polis” (city). History doesn’t record the exact conversation that led to the naming of Thermopolis, but it is said to have involved whiskey, outlaws, and a cowboy with a thick Irish brogue who convinced the townspeople it was the perfect name.

At some point it was decided that the Shoshoni Tribe would sell the area to the “white man” but there were to  be some stipulations. In 1896, Chief Washakie and the Eastern Shoshone tribe sold the land with one important condition: the springs must remain free and accessible to the public forever. They knew that the “healing waters” were such a great help to people with multiple conditions, one of which was rheumatoid arthritis. The springs contain calcium, magnesium, sodium, and sulfates that are known to help with joint pain and skin conditions. I remember hearing about my grandmother, Anna Schumacher Spencer being taken to soak in the waters at the Bath House in Thermopolis to help with her pain and stiffness. Chief Washakie knew that there would be many people who would need the waters, and in his wisdom, he made sure it would always be available.

be some stipulations. In 1896, Chief Washakie and the Eastern Shoshone tribe sold the land with one important condition: the springs must remain free and accessible to the public forever. They knew that the “healing waters” were such a great help to people with multiple conditions, one of which was rheumatoid arthritis. The springs contain calcium, magnesium, sodium, and sulfates that are known to help with joint pain and skin conditions. I remember hearing about my grandmother, Anna Schumacher Spencer being taken to soak in the waters at the Bath House in Thermopolis to help with her pain and stiffness. Chief Washakie knew that there would be many people who would need the waters, and in his wisdom, he made sure it would always be available.

For many other people, the warm waters of Thermopolis provide a wonderful place to relax and just have fun. They are a popular weekend getaway, and a great place to take the kids during Spring Break. People come from all over the state of Wyoming, as well as the surrounding states and even from other states and countries, just

to enjoy the warm water and the peaceful surroundings. Thermopolis is a small town, and there isn’t a lot to do. The dinosaur museum, the buffalo preserve, and the pools make up most of the “attractions” and the trails add a few other things to do, or those who like to hike, like me. I think the lack of activities appeals to me the most…that and the mineral hot tub, of course. That’s my favorite part.

to enjoy the warm water and the peaceful surroundings. Thermopolis is a small town, and there isn’t a lot to do. The dinosaur museum, the buffalo preserve, and the pools make up most of the “attractions” and the trails add a few other things to do, or those who like to hike, like me. I think the lack of activities appeals to me the most…that and the mineral hot tub, of course. That’s my favorite part.

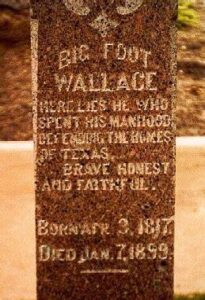

William Alexander Anderson Wallace was born in Lexington, Virginia on April 3, 1817, parents of Scots-Irish descent. He might have stayed in Virginia, but in 1836, when he was just 19 years old, Wallace received news that one of his brothers had been killed in the Battle of Goliad, which was an early confrontation in the Texan war of independence with Mexico. Wallace promised to “take pay of the Mexicans” for his brother’s death. So, with revenge on his mind, Wallace left Lexington and headed for Texas. Upon his arrival, Wallace found that the war was already over. With no further need of his anger-revenge agenda, Wallace found he liked the spirited independence of the new Republic of Texas and decided to stay.

William Alexander Anderson Wallace was born in Lexington, Virginia on April 3, 1817, parents of Scots-Irish descent. He might have stayed in Virginia, but in 1836, when he was just 19 years old, Wallace received news that one of his brothers had been killed in the Battle of Goliad, which was an early confrontation in the Texan war of independence with Mexico. Wallace promised to “take pay of the Mexicans” for his brother’s death. So, with revenge on his mind, Wallace left Lexington and headed for Texas. Upon his arrival, Wallace found that the war was already over. With no further need of his anger-revenge agenda, Wallace found he liked the spirited independence of the new Republic of Texas and decided to stay.

Wallace was a big man, standing over six feet tall and weighing around 240 pounds. His size alone made him an intimidating figure, but his nickname of “Big Foot” came from his unusually large feet. Wallace didn’t think he would ever get the chance to fight Mexicans, but in 1842, he finally got his chance when he joined with other Texans to stop an invasion by the Mexican General Adrian Woll. During another skirmish with Mexicans, Wallace was captured, and he spent the next two years serving hard time in the notoriously brutal Perote Prison in Vera Cruz. He was finally released in 1844.

After his time as a prisoner of war, Wallace returned to Texas and found himself feeling tired of the rigidness of the formal Texan military force. So, he decided to leave the military for the less rigid organization of the Texas Rangers. The Texas Ranger program was part law-enforcement officers and part soldiers. They fought both bandits and Native Americans in the large, but sparsely populated reaches of the Texan frontier. “Big Foot” Williams served under the famous Ranger John Coffee Hays until the start of the Civil War in 1861. Williams was against the idea of Texas secession from the Union, but he was unwilling to fight against his own people. He had really assimilated himself into Texas…it was a big part of him. Williams spent most of the Civil War defending Texas against Native American attacks along the frontier. He didn’t get involved in the “politics” of the matter, he just knew that he was now a Texan, and he had to defend her at all costs.

Wallace spent many years in the wilds of Texas, having hundreds of adventures. He was attacked by Native Americans while working as a stage driver on the dangerous San Antonio-El Paso route. In that event, he

barely escaped with his life. The Natives stole his mules and left him stranded in the Texas desert. Forced to walk all the way to El Paso, he later said that he ate 27 eggs at the first house he came to after his long walk. Then, he went into town to have a “real meal.”

barely escaped with his life. The Natives stole his mules and left him stranded in the Texas desert. Forced to walk all the way to El Paso, he later said that he ate 27 eggs at the first house he came to after his long walk. Then, he went into town to have a “real meal.”

After many years and many adventures and in his old age, Wallace decided he had enough of life as a fighter and adventurer. He was tired and ready to learn how to relax. The state of Texas, in exchange for his years of service, granted Wallace land along the Medina River and in Frio County in the southern part of the state. Wallace loved to tell anyone who would listen, with highly embellished tales of his frontier days. Soon he became a well-known folk hero to the people of Texas. Wallace died on January 7, 1899. He is buried in the Texas State Cemetery.

During the Revolutionary War, the United States, being a small start-up nation did not have huge amounts of funds to build a strong navy to fight against the influx of British ships sent to try to force our nation back under the rule of Great Britain, so being the resourceful nation they were, the Continental Congress made the decision to give privateers permission to attack any and all British ships on April 3, 1776. The bill was signed by John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress at that time. The bill issued “INSTRUCTIONS to the COMMANDERS of Private Ships or vessels of War, which shall have Commissions of Letters of Marque and Reprisal, authorizing them to make Captures of British Vessels and Cargoes.”

During the Revolutionary War, the United States, being a small start-up nation did not have huge amounts of funds to build a strong navy to fight against the influx of British ships sent to try to force our nation back under the rule of Great Britain, so being the resourceful nation they were, the Continental Congress made the decision to give privateers permission to attack any and all British ships on April 3, 1776. The bill was signed by John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress at that time. The bill issued “INSTRUCTIONS to the COMMANDERS of Private Ships or vessels of War, which shall have Commissions of Letters of Marque and Reprisal, authorizing them to make Captures of British Vessels and Cargoes.”

The private commercial ships were given “Letters of Marque and Reprisal” which were the official documents by which 18th-century governments commissioned private commercial ships, known as privateers, to act on their behalf. With these documents, they were officially allowed to start attacking ships carrying the flags of enemy nations. The motivation for the “assignments” was that any goods captured by the privateer were to be divided between the ship’s owner and the government that had issued the letter. It was a pretty good deal for the privateer, because they could then sell or use the good, or sell them for a profit. It was also a good deal for the government, because the received half of the “spoils” and they didn’t have to pay the privateer. As for the British ships…well, the deal was not so good.

The orders given to the privateers by Congress were “YOU may, by Force of Arms, attack, subdue, and take all Ships and other Vessels belonging to the Inhabitants of Great Britain, on the high seas, or between high-water and low-water Marks, except Ships and Vessels bringing Persons who intend to settle and reside in the United Colonies, or bringing Arms, Ammunition or Warlike Stores to the said Colonies, for the Use of such Inhabitants thereof as are Friends to the American Cause, which you shall suffer to pass unmolested, the Commanders thereof permitting a peaceable Search, and giving satisfactory Information of the Contents of the Ladings, and Destinations of the Voyages.”

The reality was that whether they were called privateers or pirates, the real distinction between the two was non-existent, at least to those who faced them on the high seas. The men were given the right to behave just

like pirates, so they behaved just like pirates, boarding and capturing ships and using force if necessary. The good news for the privateers was that privateers holding Letters of Marque were not subject to prosecution by their home nation and, if captured, were treated as prisoners of war instead of criminals by foreign nations. Even if they were caught, this was the best-case scenario for the privateers, and they were the best thing for this country at that important time in our history.

like pirates, so they behaved just like pirates, boarding and capturing ships and using force if necessary. The good news for the privateers was that privateers holding Letters of Marque were not subject to prosecution by their home nation and, if captured, were treated as prisoners of war instead of criminals by foreign nations. Even if they were caught, this was the best-case scenario for the privateers, and they were the best thing for this country at that important time in our history.

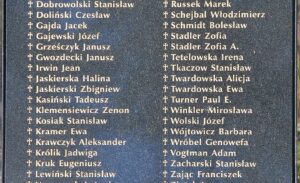

LOT Polish Airlines Flight 165 was a doomed Antonov AN-24 aircraft, registration SP-LTF. The plane operated as a scheduled passenger flight from Warsaw to Krakow Balice airport. Normally the 153-mile flight is a simple short hop, but on April 2, 1969, at 4:08pm local time the flight crashed into a mountain during a snowstorm. All 53 people on board were killed.

LOT Polish Airlines Flight 165 was a doomed Antonov AN-24 aircraft, registration SP-LTF. The plane operated as a scheduled passenger flight from Warsaw to Krakow Balice airport. Normally the 153-mile flight is a simple short hop, but on April 2, 1969, at 4:08pm local time the flight crashed into a mountain during a snowstorm. All 53 people on board were killed.

In 1969, crash investigation was not what it is today, and so a lot of the known information about the accident actually comes from two newspaper articles that were published in 1994. Of course, that doesn’t mean that no investigation took place, but from the sound of things, the documentation there has been kept classified according to the author who wrote that, “even 25 years after the accident, most documentation on the crash remains classified.” The information the author was able to gather came from the accounts of participants in the rescue action and some members of the accident investigation commission, but they asked for anonymity.

What is known and documented about the accident is that the aircraft took off from Warsaw at 3:20pm local time for a 55-minute flight to Krakow’s Balice Airport. The captain was Czeslaw Dolinski. The first officer received instructions at 3:49pm, to descend to 4,900 feet and to contact Balice control tower after passing Jedrzejów, which was less than 50 miles north of Krakow. At the time of the instructions, a military radar registered the aircraft at 13,000 feet. The pilots informed controllers in Okecie and Balice when the plane had passed the Jedrzejów VOR but there was some confusion when they provided three different passage times a few minutes apart. Shortly thereafter and before 4:00pm, the captain, who had taken over control at that point, called Balice. Dolinski gave his altitude as 12,100 feet, received the local weather report, and then was instructed to descend to 3,900 feet.

At 4:01pm, the aircraft was recorded at 7,900 feet and descending. Several radio exchanges took place between the place and the Balice radar operator over the next eight minutes, with the captain repeatedly asking for his fix and reporting problems with the beacon signal, and the operator asking for the aircraft’s position and altitude to help him find the aircraft on the radar screen. It was as if both the captain and the radar operator were confused as to where the plane was and at what altitude. At 4:05pm, the aircraft was noted near Maków Podhalanski, some 31 miles past Krakow…and at an altitude of 3,900 feet. The last transmission received from the airplane was, “Left turn to further…-” at 4:08.17pm. Seconds after that, radio contact was lost. It was at that moment that the plane crashed on the northern slope of Polica mountain, near Zawoja, southern Poland. the plane was located on the mountain side at an altitude of 3,900 feet.

The official death toll of 53 is still in question. The LOT Flight 165 manifest included 53 passengers and 5 crew members, but two days after the crash Polish press agencies published, 46 surnames, some without an address or name. According to the records, the passengers were 49 Poles, 3 Americans, and a Briton. The official

accident report, published in 1970, blamed the accident on the captain becoming lost. No one knew why the captain, just before the crash, was flying at low altitude some 31 miles past its intended destination. I don’t suppose it will ever be known for sure, or if it is, the fact that the documentation is classified will keep the truth from everyone anyway.

accident report, published in 1970, blamed the accident on the captain becoming lost. No one knew why the captain, just before the crash, was flying at low altitude some 31 miles past its intended destination. I don’t suppose it will ever be known for sure, or if it is, the fact that the documentation is classified will keep the truth from everyone anyway.

Whether you or I prank anyone on this day makes no difference. This is the day for it. Why would anyone think that we need a day to be set aside whereby it was perfectly “legal” to play multiple tricks on people? Maybe they thought that after a long dreary winter, we needed a day to just get silly. Sounds good to me. I love a good prank as much as the next guy. I can’t say that I have always been good at pranking, and I can’t say some pranks haven’t blown up in my face…apparently not everyone likes to be pranked. Go figure!! I think for me is stems from my childhood years when my sisters and I tried to pull every April Fools’ Day joke we could think of on friends or family who happened to cross our paths.

Whether you or I prank anyone on this day makes no difference. This is the day for it. Why would anyone think that we need a day to be set aside whereby it was perfectly “legal” to play multiple tricks on people? Maybe they thought that after a long dreary winter, we needed a day to just get silly. Sounds good to me. I love a good prank as much as the next guy. I can’t say that I have always been good at pranking, and I can’t say some pranks haven’t blown up in my face…apparently not everyone likes to be pranked. Go figure!! I think for me is stems from my childhood years when my sisters and I tried to pull every April Fools’ Day joke we could think of on friends or family who happened to cross our paths.

While many possible origins for the national prank day exist, no one truly seems to know where or when it started. Maybe the origins story is a joke in its own right. It could be that whenever and wherever it got started, the initiator decided to say that the tradition started somewhere else so that they could say that they were just following the tradition they had heard about. That idea isn’t so farfetched, now, is it? Somebody, somewhere had to get this started. Still, maybe for those who don’t like being pranked, the originator didn’t want to take the blame. That makes sense to me too. If you have ever been “that guy” who pranked someone with no sense of humor, you know that you would gladly blame someone else…anyone else for making you do such a thing.

I’m just thankful that it was a tradition in our family…from our parents, Al and Collene Spencer, all the way down to my sisters, Cheryl Masterson, Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, and Allyn Hadlock…and then on to the

generations beyond. People really should be taught at a young age to take a joke, and even to laugh at ourselves when we’ve been had. It’s a well-known fact, even from the Bible…Proverbs 17:22, “Laughter is like taking good medicine.” It is true, and even medicine has agreed that laughter is good for you. Laughter reduces stress, strengthens the immune system, boosts mood, and diminishes pain…just to name a few good things about laughter. So, for all you people who have no sense of humor…lighten up and laugh a little. You know you want to!! Happy April Fools’ Day everyone!!

generations beyond. People really should be taught at a young age to take a joke, and even to laugh at ourselves when we’ve been had. It’s a well-known fact, even from the Bible…Proverbs 17:22, “Laughter is like taking good medicine.” It is true, and even medicine has agreed that laughter is good for you. Laughter reduces stress, strengthens the immune system, boosts mood, and diminishes pain…just to name a few good things about laughter. So, for all you people who have no sense of humor…lighten up and laugh a little. You know you want to!! Happy April Fools’ Day everyone!!

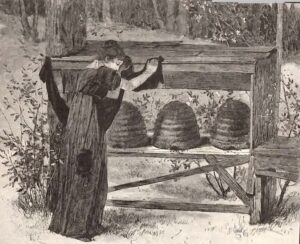

In a long-standing Western European tradition, the bees must be told of important events in the lives of their owners. Things such as deaths, births, marriages, and departures and returns in the keeper’s household. It is believed that the bees need to go through a mourning process to keep them emotionally healthy. If this practice was omitted or forgotten, and the bees were not “put into mourning,” then it was believed a penalty would be paid, such as the bees leaving their hive, stopping the production of honey, or even dying. Such a thing seems strange to anyone who has never had anything to do with bees, but who knows. Maybe they know, just like a dog or a cat knows their owner is gone. Best known in England, the practice has also been recorded in Ireland, Wales, Germany, Netherlands, France, Switzerland, Bohemia (now Czechia) and the United States.

In a long-standing Western European tradition, the bees must be told of important events in the lives of their owners. Things such as deaths, births, marriages, and departures and returns in the keeper’s household. It is believed that the bees need to go through a mourning process to keep them emotionally healthy. If this practice was omitted or forgotten, and the bees were not “put into mourning,” then it was believed a penalty would be paid, such as the bees leaving their hive, stopping the production of honey, or even dying. Such a thing seems strange to anyone who has never had anything to do with bees, but who knows. Maybe they know, just like a dog or a cat knows their owner is gone. Best known in England, the practice has also been recorded in Ireland, Wales, Germany, Netherlands, France, Switzerland, Bohemia (now Czechia) and the United States.

It is unknown how this practice got started, or where it stared exactly, but unfounded speculation has it that it  is loosely derived from or perhaps inspired by ancient Aegean notions about bees’ ability to bridge the natural world and the afterlife. There were many notions that people of ancient times believed, so I suppose this could be one of them.

is loosely derived from or perhaps inspired by ancient Aegean notions about bees’ ability to bridge the natural world and the afterlife. There were many notions that people of ancient times believed, so I suppose this could be one of them.

The whole practice has a number of strange parts to it and probably came from superstition. Apparently, it is tradition to give a piece of wedding cake or a funeral biscuit to the bees at wedding and funerals. This is done to inform the bees at the same time of the name of the party married or dead. Apparently, if the bees do not know about the marriage, they become very irate, and sting everybody within their reach. If they are ignorant of the death, they become sick, and many of them die. That might possibly speak to something similar to a pet losing its master. In the case of a death, it would inform them of a new owner. Again, this reminds me of a pet mourning an owner, even when they are shown love by the new owner. Animals can show love, maybe bees can too.

The practice even extends to the royal family. After the passing of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, the Royal Beekeeper, John Chapple, went out to inform the bees of Buckingham Palace and Clarence House of her passing and the accession of King Charles III. There is a proper process for informing the bees. According to Chapple, “You knock on each hive and say, “The mistress is dead, but don’t you go. Your master will be a good master to you.” Often the hive is also given a black sash for mourning. The purpose of all this is to ensure the health of the bees and the continuation of their honey production. It’s a strange, but interesting tradition.