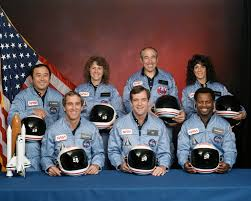

Tragedy never really goes away. Of course, it forever stays with the families of the lost, but some tragedies leave us with deeper feelings than other tragedies. Some tragedies touch our very core. Of course, those tragedies are the kind that are known, and felt, around the world. Like every national tragedy, we remember where we were when we first heard about the Challenger Disaster. Nasa had been losing its draw to a degree, but this mission was to be the first time a civilian would go up in space, and NASA had chosen a teacher for that all important mission. Her name was Christa McAuliffe. Of course, she was only one member of that tragic mission, and truly no more or less important than any of the others. These people had worked hard to become a team. The names of the rest of the crew were Dick Scobee (Commander), Michael J Smith (Pilot), Ronald McNair (Mission Specialist), Ellison Onizuka (Mission Specialist), Judith Resnik (Mission Specialist), and Gregory Jarvis (Payload Specialist).

Tragedy never really goes away. Of course, it forever stays with the families of the lost, but some tragedies leave us with deeper feelings than other tragedies. Some tragedies touch our very core. Of course, those tragedies are the kind that are known, and felt, around the world. Like every national tragedy, we remember where we were when we first heard about the Challenger Disaster. Nasa had been losing its draw to a degree, but this mission was to be the first time a civilian would go up in space, and NASA had chosen a teacher for that all important mission. Her name was Christa McAuliffe. Of course, she was only one member of that tragic mission, and truly no more or less important than any of the others. These people had worked hard to become a team. The names of the rest of the crew were Dick Scobee (Commander), Michael J Smith (Pilot), Ronald McNair (Mission Specialist), Ellison Onizuka (Mission Specialist), Judith Resnik (Mission Specialist), and Gregory Jarvis (Payload Specialist).

We all think we know what happened that fateful day…an explosion, right? Not exactly. Just 73 seconds after liftoff, the space shuttle was engulfed in what is now being called a cloud of fire, at an altitude of 46,000 feet. It looked like an explosion, the media called it an explosion, and even NASA officials mistakenly described it that way initially. Nevertheless, the reality is that in fact, there was no detonation or explosion…at least not in the way we understand an explosion to be. Actually, a seal, manufactured years before the launch, in the shuttle’s right solid-fuel rocket booster designed to prevent leaks from the fuel tank during liftoff weakened in the frigid temperatures in Florida that day. When the seal failed, hot gas began pouring through the leak. Instead of exploding, the fuel tank actually collapsed and tore apart, and the resulting flood of liquid oxygen and hydrogen created the huge fireball believed by many to be an explosion, but it was actually just a fire.

The Challenger didn’t disintegrate right away. In fact, it remained momentarily intact and actually continued moving upwards with its forward momentum. Then, as it shot forward, powerful aerodynamic forces actually pulled the orbiter apart. The pieces…including the crew cabin…reached an altitude of about 65,000 feet before losing its momentum and falling out of the sky into the Atlantic Ocean below. At that point, the crew, who had most likely survived the initial breakup of the shuttle, was unconscious due to loss of cabin pressure and probably died due to oxygen deficiency pretty quickly. The cabin hit the water’s surface traveling at speeds of more than 200 miles per hour. It hit the water a full 2 minutes and 45 seconds after the shuttle broke apart. No one knows if the crew might have regained consciousness in the final few seconds of the fall, and I certainly hope that is not the case. I would much rather that they had no idea what was coming, and if they were awake, they certainly would have known. We will never know, of course.

Salvage operations began immediately, and I’m sure that they hoped against hope to be able to find some of the crew still alive. Within a day of the shuttle tragedy, salvage operations had recovered hundreds of pounds of metal from the Challenger. As hopes turned to sad resolve, the salvage operation continued. They kept looking and finally in March 1986, the remains of the astronauts were found in the debris of the crew cabin. By the time NASA closed its Challenger investigation in 1986, all of the important pieces of the shuttle were retrieved. Nevertheless, most of the spacecraft remained in the Atlantic Ocean, where I’m sure, they thought it would remain. Then, a decade later, eerie memories of the disaster resurfaced when two large pieces of the Challenger washed up in the surf at Cocoa Beach, about 20 miles south of the Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral. NASA believed the two barnacle-encrusted fragments came from the shuttle’s left wing flap. It is

thought that the two pieces were once connected. One piece measured more than 6 feet wide and 13 feet long. Once they were officially verified, the pieces of Challenger were placed in two abandoned missile silos with the other shuttle remains, which number around 5,000 pieces and weigh in at some 250,000 pounds.

thought that the two pieces were once connected. One piece measured more than 6 feet wide and 13 feet long. Once they were officially verified, the pieces of Challenger were placed in two abandoned missile silos with the other shuttle remains, which number around 5,000 pieces and weigh in at some 250,000 pounds.

One Response to What We Now Know