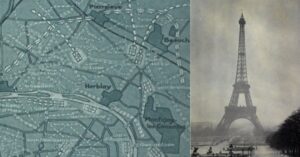

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

London’s Daily Telegraph explains that the fake city wasn’t just “a bunch of cardboard cutouts.” No, far from it, in fact. There were “electric lights, replica buildings, and even a copy of the Gare du Nord—the station from which high-speed trains now travel to and from London.” The painters went so far as to use paint to create “the impression of dirty glass roofs of factories.” Fake trains and railroad tracks were lit up as well. There was a phony Champs-Elysées. Many of us today would say, “How could that work? The Germans must have known where they were dropping their bombs!” Nevertheless, it stands to reason that in the early 20th century, the plan could have worked. “Radar was in its infancy in 1918, and the long-range Gotha heavy bombers being used by the German Imperial Air Force were similarly primitive,” the Telegraph notes. “Their crew would hold bombs by the fins and then drop them on any target they could see during quick sorties over major cities like Paris and London.”

No one really knows how well the plan might have worked, because it was never put to the test. World War I ended before the fake city was finished. Both the real Paris and the fake one escaped significant damage. The fake version has long since been dismantled, though photos of it still remain. I suppose it was a ghost town of  it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

To further validate the idea, French fighter pilots reported that during night flights they looked for familiar features of the landscape below when attempting to locate Paris. According to their research, railways, lakes, rivers, roads and woodland were the most useful indicators that they were in the neighborhood. Using this information, the mastermind behind the replica project, Fernand Jacopozzi, along with his team of highly capable engineers worked to make life even harder for the German pilots who were already struggling to find their bearings in an era before radar or precision targeting. Intending to confuse an enemy pilot sufficiently that he would start to doubt his own bearings, the construction of Paris’ mirror image began in earnest at Villepinte to the northeast where a working model of the Gare de l’Est gradually began to take form.

The “fake Paris” was exquisite. No detail was overlooked: “complex, sprawling networks of lights arranged skillfully creating the impression of railway tracks and avenues, as well as storm lamps clustered together on ingenious moving platforms designed to simulate vast steam trains in motion. Immense empty sheds masquerading as factories had translucent sheets of painted canvas stretched tightly across their wooden frames which were illuminated from underneath, an arrangement that to anyone passing overhead would look remarkably like the dirty glass roofs characteristic of industrial buildings. Working furnaces were also installed to add an extra dimension of reality and the factory’s lights were even configured to dim noticeably during an air raid, fooling enemy pilots into believing that the facsimile buildings were, in fact, occupied.”

Because World War I ended, it was only this small part of Zone A that was built. The German bombing campaign came to an end in September 1918 and the armistice was signed at Compiègne two months later. The mock factories and railway network at Villepinte were dismantled shortly after the hostilities ceased. By the beginning of the 1920s little remained of the project. Though his fascinating idea never really got much further than the drawing board, the designs of Fernand Jacopozzi inspired similarly ambitious plans in the United States during World War II.

One Response to Stunt Double