A few days ago, my friends, Rikki and Tony Ramsey (who is stationed in Germany) and their three sons, Jameson, Jackson, and Jordan posted some pictures of a trip they took to Salzburg, Austria. On the way there, they went to a place in the mountains, and posted pictures of them in front of a large cross. It was the cross that caught my eye, but the story of the place that held my interest. In English the place is called the Eagle’s Nest, but in German it is the Kehlsteinhaus and it is a building and cross erected by the Third Reich atop the summit of the Kehlstein, a rocky outcrop that rises above Obersalzberg near the town of Berchtesgaden. This was not a church or a fancy mountain-top resort or restaurant…at least not then. It was used exclusively by members of the Nazi Party for government and social meetings, and was visited on 14 documented instances by Adolf Hitler, who disliked the location due to his fear of heights, the risk of bad weather, and the thin mountain air. Today, the building is owned by a charitable trust and is open seasonally to the public as a restaurant, beer garden, and tourist site. I’m sure Hitler would be furious about that.

A few days ago, my friends, Rikki and Tony Ramsey (who is stationed in Germany) and their three sons, Jameson, Jackson, and Jordan posted some pictures of a trip they took to Salzburg, Austria. On the way there, they went to a place in the mountains, and posted pictures of them in front of a large cross. It was the cross that caught my eye, but the story of the place that held my interest. In English the place is called the Eagle’s Nest, but in German it is the Kehlsteinhaus and it is a building and cross erected by the Third Reich atop the summit of the Kehlstein, a rocky outcrop that rises above Obersalzberg near the town of Berchtesgaden. This was not a church or a fancy mountain-top resort or restaurant…at least not then. It was used exclusively by members of the Nazi Party for government and social meetings, and was visited on 14 documented instances by Adolf Hitler, who disliked the location due to his fear of heights, the risk of bad weather, and the thin mountain air. Today, the building is owned by a charitable trust and is open seasonally to the public as a restaurant, beer garden, and tourist site. I’m sure Hitler would be furious about that.

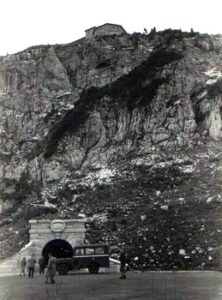

The Kehlsteinhaus is located on a ridge atop the Kehlstein, a 6,017 feet subpeak of the Hoher Göll that rises above the town of Berchtesgaden. It construction was commissioned by Martin Bormann in the summer of 1937, and paid for by the Nazi Party. It took 13 months to complete, and whether is was the speed of its construction, or simply poor safety standards, twelve workers died during its construction. The road to Kehlsteinhaus is 13 feet wide and climbs 2,600 feet over 4 miles. To get to Kehlsteinhaus, the road goes through five tunnels and one hairpin turn. The road cost RM 30 million to build (about €150 million inflation-adjusted for 2007), which equals about 180,450,000 US dollars. Hitler’s birthday in April 1939 was considered a deadline for the project’s completion, so work continued throughout the winter of 1938, even at night with the worksite lit by searchlights. That explains the twelve deaths, I suppose.

Once you arrive, there is a large car park. From there, a 407 feet entry tunnel leads to an ornate elevator that ascends the final 407 feet to the building. Even the tunnel was elaborate. It was lined with marble and was originally heated, with warm air from an adjoining service tunnel. Most people walked into the elevator, but visiting high-officials were commonly driven through the tunnel to the elevator. Since the tunnel was to narrow to turn around, the driver then had to reverse the car for the entire length of the tunnel. The elevator was elaborate too, of course. The inside was surfaced with polished brass, Venetian mirrors, and green leather. The building’s main reception room is dominated by a fireplace of red Italian marble presented by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, which was damaged by Allied soldiers chipping off pieces to take home as souvenirs. Hitler had the best of everything in the building. Unusual for 1937, the building had a completely electric appliance

kitchen, but it was never used to cook meals…instead meals were prepared in town and taken to the kitchen on the mountain top to be reheated. Another extravagancy was the heated floors, with heating required for at least two days before visitors arrived. A MAN submarine diesel engine and an electrical generator were installed in an underground chamber close to the main entrance, to provide back-up power. Much of the furniture was designed by Paul László.

kitchen, but it was never used to cook meals…instead meals were prepared in town and taken to the kitchen on the mountain top to be reheated. Another extravagancy was the heated floors, with heating required for at least two days before visitors arrived. A MAN submarine diesel engine and an electrical generator were installed in an underground chamber close to the main entrance, to provide back-up power. Much of the furniture was designed by Paul László.

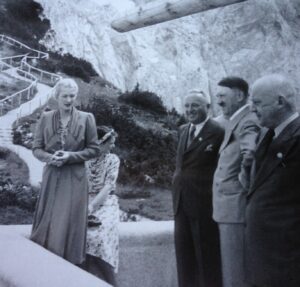

Hitler first visited on September 16, 1938, and returned to inaugurate it on April 20, 1939, his 50th birthday…though supposedly, it was not intended as a birthday gift. There are two ways to approach and enter the building…the road and the Kehlsteinhaus elevator. Hitler did not trust the elevator, continually expressed his reservations of its safety, and disliked using it. His biggest fear was that the elevator’s winch mechanism on the roof would attract a lightning strike. Bormann took great pains to never mention the two serious lightning strikes that occurred during construction. For a man who was supposedly such a “brave leader,” Hitler sure was afraid of a lot of things. The Kehlsteinhaus lies several miles directly above the Berghof, Hitler’s summer home. In a rare diplomatic engagement, Hitler received departing French ambassador André François-Poncet on October 18, 1938, there. It was he who actually came up with the name “Eagle’s Nest” for the building while later describing the visit. Since then, the name has remained. A wedding reception for Eva Braun’s sister Gretl was held there following her marriage to Hermann Fegelein on June 3, 1944. While Hitler more often than not left the entertaining duties to others, he believed the house presented an excellent opportunity to entertain important and impressionable guests. Often referred to as the “D-Haus,” short for “Diplomatic Reception House,” the Kehlsteinhaus is often combined with the teahouse on Mooslahnerkopf Hill near the Berghof, which Hitler walked to daily after lunch. Later, after the war, the teahouse was demolished by the Bavarian government, due to its connection to Hitler.

The Allies tried to bomb the Kehlsteinhaus in the April 25, 1945 Bombing of Obersalzberg, but the little house did not make an easy target for the force of 359 Avro Lancasters and 16 de Havilland Mosquitoes, which were sent to bomb Kehlsteinhaus, but instead, severely damaged the Berghof area. Undamaged in the April 25 bombing raid, the Kehlsteinhaus was subsequently used by the Allies as a military command post until 1960, when it was handed back to the State of Bavaria. The road to the Kehlsteinhaus has been closed to private vehicles since 1952 because it is too dangerous, but the house can be reached on foot (in two hours) from Obersalzberg, or by bus from the Documentation Center there. The Documentation Centre currently directs visitors to the coach station where tickets are purchased. The buses have special modifications to take on a

slight angle, as the steep road leading to the peak is too steep for regular vehicles. The Kehlsteinhaus itself does not mention much about its past, except in the photos displayed and described along the wall of the sun terrace that documents its pre-construction condition until now. The lower rooms of the structure are not part of the restaurant but can be visited with a guide. They offer views of the building’s past through plate-glass windows, including graffiti left by Allied troops that is still visible in the surrounding woodwork. The red Italian marble fireplace remains damaged by Allied souvenir hunters, though this was later halted by signage posted that the building was US government property, and damage to it was cause for disciplinary action. Hitler’s small study is now a storeroom for the cafeteria. Thanks to the Ramsey family for taking us along.

slight angle, as the steep road leading to the peak is too steep for regular vehicles. The Kehlsteinhaus itself does not mention much about its past, except in the photos displayed and described along the wall of the sun terrace that documents its pre-construction condition until now. The lower rooms of the structure are not part of the restaurant but can be visited with a guide. They offer views of the building’s past through plate-glass windows, including graffiti left by Allied troops that is still visible in the surrounding woodwork. The red Italian marble fireplace remains damaged by Allied souvenir hunters, though this was later halted by signage posted that the building was US government property, and damage to it was cause for disciplinary action. Hitler’s small study is now a storeroom for the cafeteria. Thanks to the Ramsey family for taking us along.

Leave a Reply