These days, everyone is fighting for a higher minimum wage, but in may years gone by, people were happy to get what little they were given. The Great Depression was one of those times for sure, but there were others. On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford and his vice president James Couzens absolutely stunned the world when they announced that Ford Motor Company would double its workers’ wages to five dollars a day. Now in this day and age, the workers would just go out and look for another job if that was offered, but back then, they were all going to be rich!! Of course, newspapers around the world were gushing with the great news. The notion of a wealthy industrialist sharing profits with workers on such a scale was unprecedented. Everyone wanted to work for Ford.

These days, everyone is fighting for a higher minimum wage, but in may years gone by, people were happy to get what little they were given. The Great Depression was one of those times for sure, but there were others. On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford and his vice president James Couzens absolutely stunned the world when they announced that Ford Motor Company would double its workers’ wages to five dollars a day. Now in this day and age, the workers would just go out and look for another job if that was offered, but back then, they were all going to be rich!! Of course, newspapers around the world were gushing with the great news. The notion of a wealthy industrialist sharing profits with workers on such a scale was unprecedented. Everyone wanted to work for Ford.

In the century since, many people have theorized that the increased pay was to justify assembly line speed-ups, while others speculated it was to counteract high labor turnover due to increasingly monotonous assembly line work. Those who were fans of Ford called it pure philanthropy. Those who didn’t like Ford called it little more than an elaborate publicity stunt…maybe to gain fame or to brag about his successes, but the truth was likely a little of both. A successful boss should share his successes with those who helped him to achieve the level of success he has gained. Of course, not all do, and my guess is that those who wouldn’t do that are the ones who screamed the loudest. There is no pain in business bigger that when someone does the right thing when you won’t.

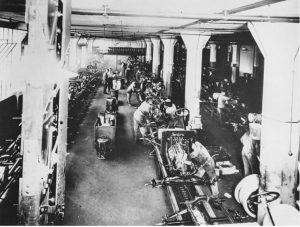

In order to really understand why Ford implemented the Five-Dollar Day, one must realize that his advances in the moving assembly line, and experiments through 1913 and into 1914 reduced the time required to build a Model T automobile from 12½ hours to just 93 minutes. Increased efficiencies lowered production costs, which lowered customer prices, which increased demand. The public was eager to buy all of the cars Ford could build. That meant that he needed to increase production, and good help is always hard to find. When you find good workers, you should pay them well. Explosive production gains came at the cost of worker satisfaction. The workers were skilled in their little area of the project, and after a while, doing the same job over and over again can get monotonous. The very goal of the moving assembly line was to take what had been relatively skilled craftwork and reduce it to simple, rote tasks. Workers who had previously taken pride in their skilled labor were quickly bored, and some took to lateness and absenteeism. Many simply quit, and Ford found itself with a crippling labor turnover rate of 370 percent. The assembly line was a great invention, but it was hard on the workers, and the assembly line depended on a steady crew to run it. Training replacements was expensive and time consuming, so Ford decided that a bigger paychecks might make the factory’s tedious labor more tolerable.

The increased wages may have seemed like the best solution, but it backfired in a way. The need to retain workers and the subsequent Five-Dollar Day as an effort to do so, worked too well in the end. Within days of the announcement, thousands of applicants came to Detroit from all over the Midwest. They parked at Ford’s gate, and immediately overwhelmed the company. Riots broke out, and the crowds were turned away with fire hoses in the icy January weather. To overcome the problem, Ford announced that it would only hire workers who had lived in Detroit for at least six months. Finally, the rioting stopped and peace returned to the area. Of course, for those who had jobs at Ford, there was the “fine print” to deal with If you made $2.30 a day under the old pay schedule, for example, you still made that wage under the Five-Dollar plan, but if you met all of the company’s requirements, Ford gave you a bonus of $2.70. I don’t suppose that garnered a lot of good feelings either. Many people couldn’t wrap their minds around the profit-sharing plan. They needed the money now.

Part of Henry Ford’s reasoning behind the Five-Dollar Day was that workers who were troubled by money problems at home would be distracted on the job. If higher pay was intended to eliminate these problems, then Ford would make sure that his employees were using his gift “properly.” The company established a Sociological Department to monitor its employees’ habits beyond the workplace. “To qualify for the pay increase, workers had to abstain from alcohol, not physically abuse their families, not take in boarders, keep their homes clean, and contribute regularly to a savings account. Moral righteousness and prudent saving were all well and good, but they were not generally an employer’s business…at least not outside of working hours. In contrast, Ford Motor Company inspectors came to workers’ homes, asked probing questions, and observed general living conditions. If ‘violations’ were discovered, the inspectors offered advice and pointed the families to resources

offered through the company. Not until these problems were corrected did the employee receive his full bonus.” At this point, I would have to say that the company was taking far too much control. Many others agreed, and by 1921, the Sociological Department was largely dissolved. The Five-Dollar Day was a good idea in the beginning, but in the end, it was one that just got a little out of control.

offered through the company. Not until these problems were corrected did the employee receive his full bonus.” At this point, I would have to say that the company was taking far too much control. Many others agreed, and by 1921, the Sociological Department was largely dissolved. The Five-Dollar Day was a good idea in the beginning, but in the end, it was one that just got a little out of control.

Leave a Reply