Born Jewish, on April 4, 1922, in Berlin, Germany, did not necessarily set Marie Jalowicz up for a long carefree life. Marie was 11 years old when the Nazi Party came to power, and soon after began to imprison her family members. By age 20, Marie was forced to fend for herself. She found herself faced with the difficult task of constantly avoiding the Nazis. For Marie, this meant somehow assimilating into German life…basically pretending to be a non-Jew. I can’t imagine having to pretend to be a nationality other than my own, but that is what she had to do. Anything about her that was Jewish had to be set aside, forgotten, or hidden from the eyes and ears of the Nazis, who seemed to be everywhere around her.

Born Jewish, on April 4, 1922, in Berlin, Germany, did not necessarily set Marie Jalowicz up for a long carefree life. Marie was 11 years old when the Nazi Party came to power, and soon after began to imprison her family members. By age 20, Marie was forced to fend for herself. She found herself faced with the difficult task of constantly avoiding the Nazis. For Marie, this meant somehow assimilating into German life…basically pretending to be a non-Jew. I can’t imagine having to pretend to be a nationality other than my own, but that is what she had to do. Anything about her that was Jewish had to be set aside, forgotten, or hidden from the eyes and ears of the Nazis, who seemed to be everywhere around her.

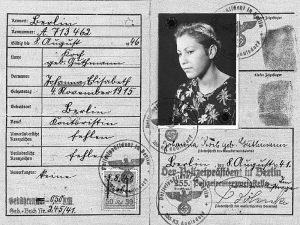

Marie knew that as the situation for Jews in Nazi Germany deteriorated, things would grow steadily worse for her. She had to somehow come up with a way to virtually hide in plain sight. When a postman wrongly delivered a letter for a job offer intended for the neighbor in 1941, she told a postman that her “neighbor” Marie was taken by the Nazis, then she simply started walking around without a star on her jacket. She was successfully living under a false identity. She took the job and began  working at the Siemens arms factory in her neighbor’s place. While living this double life, Jalowicz sabotaged production at the arms factory where she worked. Marie evaded Nazi capture through a long string of forgeries, impersonations, and help from people from every walk of life. Marie became Johanna Koch, using her wit and charm to seduce people in positions that could help her and moved around constantly. She took the words of a friend of hers to heart, “In absurd times, everything is absurd. You can save yourselves only by absurd means since the Nazis are out to murder us all.” On more than one occasion she tried to flee Germany, narrowly evading apprehension and escaping back to her homeland each time. She relocated often, and at one point was sold to an abusive Nazi with late-stage syphilis for 15 marks, which added to her cover as a non-Jew. In the coming years, she took menial jobs and lived in several Berlin flats, at times with roommates who were fervent Nazis. I can’t imagine how awful it was for her.

working at the Siemens arms factory in her neighbor’s place. While living this double life, Jalowicz sabotaged production at the arms factory where she worked. Marie evaded Nazi capture through a long string of forgeries, impersonations, and help from people from every walk of life. Marie became Johanna Koch, using her wit and charm to seduce people in positions that could help her and moved around constantly. She took the words of a friend of hers to heart, “In absurd times, everything is absurd. You can save yourselves only by absurd means since the Nazis are out to murder us all.” On more than one occasion she tried to flee Germany, narrowly evading apprehension and escaping back to her homeland each time. She relocated often, and at one point was sold to an abusive Nazi with late-stage syphilis for 15 marks, which added to her cover as a non-Jew. In the coming years, she took menial jobs and lived in several Berlin flats, at times with roommates who were fervent Nazis. I can’t imagine how awful it was for her.

Marie went on to become a German philologist and historian of philosophy, pursued a career in academia,  and received a Ph.D. in ancient literature and art history at Berlin’s Humboldt University. Then, after the war, she become a professor at Humboldt University, where she worked until her death in 1998. Just before her death she recorded 77 cassette tapes of audio with her son, Hermann. In the tapes, for the first time, Marie chronicled her experience during the Nazi reign. They were later compiled into a book called, Underground in Berlin: A Young Woman’s Extraordinary Tale of Survival in the Heart of Nazi Germany. She became known to larger audiences for this, her autobiographical account of the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany, which was published posthumously. Marie died on September 16, 1998. She returned to her original identity only on her deathbed. Her mother died of cancer in 1938. Her father died in 1941. She is survived by her only son, Hermann Simon.

and received a Ph.D. in ancient literature and art history at Berlin’s Humboldt University. Then, after the war, she become a professor at Humboldt University, where she worked until her death in 1998. Just before her death she recorded 77 cassette tapes of audio with her son, Hermann. In the tapes, for the first time, Marie chronicled her experience during the Nazi reign. They were later compiled into a book called, Underground in Berlin: A Young Woman’s Extraordinary Tale of Survival in the Heart of Nazi Germany. She became known to larger audiences for this, her autobiographical account of the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany, which was published posthumously. Marie died on September 16, 1998. She returned to her original identity only on her deathbed. Her mother died of cancer in 1938. Her father died in 1941. She is survived by her only son, Hermann Simon.

Leave a Reply