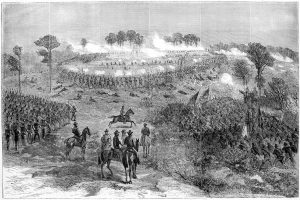

In the latter part of September 1864, in the middle of the Civil War’s second half, the Union Army targeted Fort Harrison, a key Confederate stronghold. Capturing Richmond, Virginia, hinged on taking Fort Harrison, crucial to General Butler’s offensive strategy. As the most formidable segment of the Confederate defense line, Fort Harrison offered a clear view to the James River, rendering surprise attacks nearly impossible. Following intense summer skirmishes along Petersburg, Virginia’s earthworks, and a toll of around 27,000 casualties since June, a haunting silence had settled over the region. The II Army Corps, led by Major General Winfield Hancock and previously the backbone of Major General George G Meade’s Army of the Potomac, was now severely weakened. Positioned near Petersburg, the II Army Corps was tasked with monitoring and preventing any maneuvering of General Robert E Lee’s combat forces across the James River.

In the latter part of September 1864, in the middle of the Civil War’s second half, the Union Army targeted Fort Harrison, a key Confederate stronghold. Capturing Richmond, Virginia, hinged on taking Fort Harrison, crucial to General Butler’s offensive strategy. As the most formidable segment of the Confederate defense line, Fort Harrison offered a clear view to the James River, rendering surprise attacks nearly impossible. Following intense summer skirmishes along Petersburg, Virginia’s earthworks, and a toll of around 27,000 casualties since June, a haunting silence had settled over the region. The II Army Corps, led by Major General Winfield Hancock and previously the backbone of Major General George G Meade’s Army of the Potomac, was now severely weakened. Positioned near Petersburg, the II Army Corps was tasked with monitoring and preventing any maneuvering of General Robert E Lee’s combat forces across the James River.

At that moment, Major General Benjamin Butler knew he needed to devise a strategy to turn the tide. The pause in activity presented an ideal opportunity for action. Butler considered that during such lulls, there’s often a slight drop in vigilance—just enough, he surmised, for a surprise attack. With this in mind, Butler approached Lieutenant General Ulysses S Grant with a plan. The strategy involved relocating the Army of the James north of the James River to initiate an assault on the Confederate Outer Defenses near Richmond. The objective of the Federal Army of the James was to seize control of the road network southeast of the Confederate Capital, ultimately aiming to capture Richmond itself.

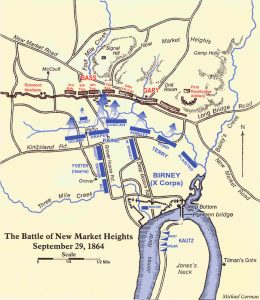

Before Petersburg, there was little activity, but the situation was changing rapidly in the Shenandoah Valley. The battle at Fisher’s Hill occurred on September 22, 1864, resulting in numerous casualties, notably the death of Brigadier General William Nelson Pendleton’s son. Grant’s staff officers were against the subsequent boat journey up the James River, yet Benjamin Butler persuaded Grant to deploy the Army of the James for a northern offensive. The strategy was straightforward. The Confederates underestimated the Federal Armies’ ability to mount a significant offensive towards Richmond from the north, as they had troops defending the earthworks there, leading them to allocate their forces elsewhere. Even with General Robert E Lee’s focus on the north, the Confederate forces in the outer defenses were critically understrength. It was believed that if a genuine threat emerged in that area, Confederate troops could swiftly reinforce the defenses before an attack could be initiated. On the night of September 28-29, 1864, Major General Benjamin Butler convened his top officers for a briefing on the planned movements of his army. Major General Edward O C Ord of the 18th Army Corps, Major General David B Birney of the 10th Army Corps, and Brigadier General August V Kautz of the Cavalry Division were present.

The strategy involved Major General Ord and the 18th Army Corps making an unexpected crossing of the James River at Aiken’s Landing, then advancing up Varina Road. Their goal was to destroy the Confederate bridges at Chaffin’s Bluff before heading up Osbourne Road towards Richmond. At the same time, the 10th Corps, led by Major General Birney, would push forward from Deep Bottom to seize New Market Heights. Moving northwest, Birney’s divisions would proceed up New Market Road towards the Confederate capital. Meanwhile, Brigadier General Kautz’s cavalry was to dash down Darbytown Road towards Richmond. Unfortunately for the South, on September 29, 1864, the plan partially unraveled when 2,500 Union soldiers from Major General Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James overwhelmed Major Richard Cornelius Taylor’s 200-man Confederate garrison, taking the fort in the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm. The operation saw the unfortunate death of Brigadier General Hiram Burnham, a brigade commander from Maine in the XVIII Corps. In his memory, Fort Harrison was subsequently renamed Fort Burnham after the Union forces assumed control.

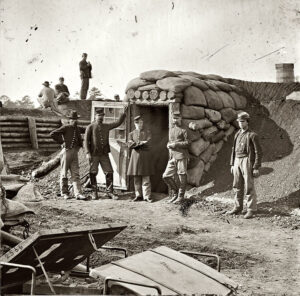

Ultimately, Fort Harrison stood as the sole victory of the day. Although the attempt to capture Richmond was unsuccessful, it quickly pointed out the region’s marked susceptibility. Recognizing the imminent threat to Richmond, General Robert E Lee then commanded a counterattack on September 30. The offensive was unsuccessful, and Brigadier General George J Stannard lost an arm during the resistance to Lee’s assault. This setback compelled the Confederates to reposition their defenses further west. Fort Harrison, also known as Fort Burnham, stayed under Union control until the war was over on November 6, 1865.

Ultimately, Fort Harrison stood as the sole victory of the day. Although the attempt to capture Richmond was unsuccessful, it quickly pointed out the region’s marked susceptibility. Recognizing the imminent threat to Richmond, General Robert E Lee then commanded a counterattack on September 30. The offensive was unsuccessful, and Brigadier General George J Stannard lost an arm during the resistance to Lee’s assault. This setback compelled the Confederates to reposition their defenses further west. Fort Harrison, also known as Fort Burnham, stayed under Union control until the war was over on November 6, 1865.

Leave a Reply