The worst fate a ship can suffer is to end up at the bottom of the sea. Nevertheless, it is a hazard that goes with the territory. Most of these lost ships simply litter the ocean floor, never seeing the light of day again, but once in a while, a ship…or part of a ship finds itself being raised up from the bottom again. Such was the case with USS Monitor, a Civil War era naval warship, that sunk to a watery grave in a storm on March 9, 1862, taking with it, 16 members of it’s crew, who were afraid to go topside in the storm.

The worst fate a ship can suffer is to end up at the bottom of the sea. Nevertheless, it is a hazard that goes with the territory. Most of these lost ships simply litter the ocean floor, never seeing the light of day again, but once in a while, a ship…or part of a ship finds itself being raised up from the bottom again. Such was the case with USS Monitor, a Civil War era naval warship, that sunk to a watery grave in a storm on March 9, 1862, taking with it, 16 members of it’s crew, who were afraid to go topside in the storm.

A short nine months before the tragedy of the USS Monitor, the ship had been part of a revolution in naval warfare. On March 9, 1862, it dueled to a standstill with the CSS Virginia in one of the most famous moments in naval history. It was the first time two ironclads ships faced each other in a naval engagement. During the battle, the two ships circled one another, jockeying for position as they fired their guns, but the cannon balls were no match for the ironclad ships, and they simply deflected off of the sides. In the early afternoon, the Virginia pulled back to Norfolk. Neither ship was seriously damaged, but the Monitor effectively ended the short reign of terror that the Confederate ironclad had brought to the Union navy. What a strange battle that must have been.

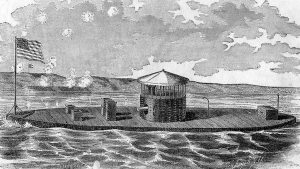

The USS Monitor was designed by Swedish engineer John Ericsson. Probably the most strange part of the design was the fact that Monitor had an unusually low profile, rising from the water only 18 inches. The ship sat so low to the water, that it could easily have resembled a submarine. The flat iron deck had a 20 foot cylindrical  turret rising from the middle of the ship. The turret housed two 11 inch Dahlgren guns. The shift had a draft of less than 11 feet so it could operate in the shallow harbors and rivers of the South. It was commissioned on February 25, 1862, and arrived at Chesapeake Bay just in time to engage the Virginia. After the famous duel with the CSS Virginia, the Monitor provided gun support on the James River for George B. McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign. By December 1862, it was clear the ship was no longer needed in Virginia, so she was sent to Beaufort, North Carolina, to join a fleet being assembled for an attack on Charleston.

turret rising from the middle of the ship. The turret housed two 11 inch Dahlgren guns. The shift had a draft of less than 11 feet so it could operate in the shallow harbors and rivers of the South. It was commissioned on February 25, 1862, and arrived at Chesapeake Bay just in time to engage the Virginia. After the famous duel with the CSS Virginia, the Monitor provided gun support on the James River for George B. McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign. By December 1862, it was clear the ship was no longer needed in Virginia, so she was sent to Beaufort, North Carolina, to join a fleet being assembled for an attack on Charleston.

The Monitor was an ideal type of ship in the sheltered waters of Chesapeake Bay, but the heavy, low-slung ship was no good in the open sea. Knowing that, the USS Rhode Island towed the ironclad around the rough waters of Cape Hatteras…a plan that would prove disastrous. As the Monitor pitched and swayed in the rough seas, the caulking around the gun turret loosened and water began to leak into the hull. More leaks developed as the journey continued. High seas tossed the craft, causing the ship’s flat armor bottom to slap the water. Each roll opened more seams, and by nightfall on December 30, it was clear that the Monitor was going to sink. That evening, the Monitor’s commander, J.P. Bankhead, signaled the Rhode Island that they needed to abandon ship. The USS Rhode Island pulled as close as safety allowed to the stricken USS Monitor, and two lifeboats were lowered to retrieve the crew. Many of the sailors were rescued, but some men were too terrified to venture onto the deck in such rough seas. The Monitor’s pumps stopped working, and the ship sank before 16 of its crew members could be rescued. It amazes me that a ship that could deflect cannon balls, was taken  down by loosened calking.

down by loosened calking.

On this day in 2002, the rusty iron gun turret of the USS Monitor rose up from the bottom of its watery grave, and into the daylight for the first time in 140 years. The ironclad warship was raised from the floor of the Atlantic, where it had rested since it went down in a storm off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, during the Civil War. Divers had been working for six weeks to bring it to the surface. The remains of two of the 16 lost sailors were discovered by divers during the Monitor’s 2002 reemergence. Many of the ironclad’s artifacts are now on display at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia.

Leave a Reply