Before it became part of Canada, the Island of Vancouver was known as the Colony of Vancouver Island, but it was officially referred to the Island of Vancouver and its Dependencies. It was a Crown colony of British North America from 1849 to 1866. Then, in 1886, it was united with the mainland to form the Colony of British Columbia. The united colony joined Canadian Confederation in 1871, thereby becoming part of Canada. The colony included Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands in the Strait of Georgia. The transitions the island made over those years are fairly common as land ownership went over the centuries.

Before it became part of Canada, the Island of Vancouver was known as the Colony of Vancouver Island, but it was officially referred to the Island of Vancouver and its Dependencies. It was a Crown colony of British North America from 1849 to 1866. Then, in 1886, it was united with the mainland to form the Colony of British Columbia. The united colony joined Canadian Confederation in 1871, thereby becoming part of Canada. The colony included Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands in the Strait of Georgia. The transitions the island made over those years are fairly common as land ownership went over the centuries.

The first European person to set foot on Vancouver Island was Captain James Cook landing first on the island at Nootka Sound in 1778 during his third voyage. Cook spent a month in the area, claiming the territory for Great Britain. Trader John Meares arrived in 1786 and established a single-building trading post near the native village of Yuquot (Friendly Cove) at the entrance to Nootka Sound in 1788. The fur trade began expanding across the island, eventually leading to permanent settlement.

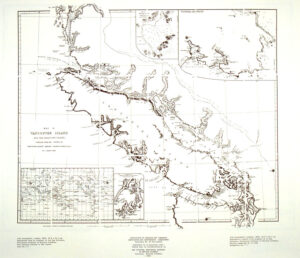

The Spanish Empire also explored the region. In 1789, Commandant Esteban José Martínez constructed a fort at Friendly Cove on Vancouver Island and seized British ships, stating that they had sovereignty. The fort was re-established in 1790 Francisco de Eliza, and a small community developed around it. Ownership of the remained contested between Spain and Britain.

In 1792, Captain George Vancouver arrived to with Spanish Commandant Juan Francisco de Bodega y Quadra. The plan was to negotiate an agreement concerning the island, but their lengthy negotiations failed to resolve the competing claims of ownership. In fact, the negotiations went so badly that the two countries nearly went to war over the issue. The negotiation-confrontation became known as the Nootka Crisis. Disaster was finally averted when both parties agreed to recognize the other’s rights to the area in the first Nootka Convention in 1790. While it was shaky, it was a preliminary step towards peace. Negotiations continued and the two countries signed the second Nootka Convention in 1793 and the third Convention in 1794. As per the final agreement, the Spanish dismantled their fort at Nootka and left the area, granting the British sovereignty over Vancouver Island and the adjoining islands, including the Gulf Islands.

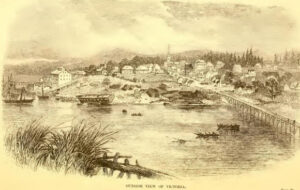

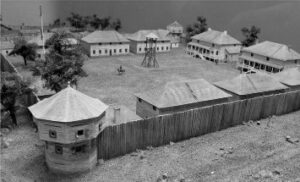

It was not until 1843 that Britain, under the auspices of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), established a settlement on Vancouver Island. In March 1843, James Douglas of the Hudson’s Bay Company and a missionary arrived and an area for settlement. Construction of the fort began in June. This settlement was a fur trading post originally named Fort Albert, later renamed Fort Victoria. The fort was located at the Songhees settlement of Camosack (Camosun), 200 meters northwest of the present-day Empress Hotel on Victoria Inner Harbour.

In 1846, the Oregon Treaty was signed by the British and the States to the question of the US Oregon Territory borders. The Treaty established the 49th parallel north latitude as the official border between the two countries. To ensure that Britain retained all of Vancouver Island and the southern Gulf Islands, however, it was agreed that the border would swing south around that area. Finally, in 1849, the Colony of Vancouver Island was established and leased to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) for ten years at an annual fee of seven shillings, which sounds almost comical these days. Consequently, HBC moved its western headquarters from Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River (present-day Vancouver, Washington) to Fort Victoria. Chief Factor James Douglas was relocated from Fort Vancouver Fort Victoria to oversee the operations west of the Rockies.

The British colonial designated the territory as a Crown colony on 13 January 1849. Douglas was tasked with encouraging British settlement. Richard Blanshard was appointed as the colony’s governor. Blanshard

discovered that the HBC’s control over the affairs of the new colony was nearly absolute, and that Douglas held practical authority in the territory. There was no civil service, no police, no militia, and virtually every colonist was an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Frustrated, Blanshard abandoned his post a year later and returned to England. In 1851, Blanshard’s resignation was finalized, and the colonial office appointed Douglas as governor.

discovered that the HBC’s control over the affairs of the new colony was nearly absolute, and that Douglas held practical authority in the territory. There was no civil service, no police, no militia, and virtually every colonist was an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Frustrated, Blanshard abandoned his post a year later and returned to England. In 1851, Blanshard’s resignation was finalized, and the colonial office appointed Douglas as governor.

Leave a Reply