During five weeks in the fall of 1718, Charleston’s citizens observed thirteen trials involving fifty-eight men charged with piracy. Piracy was and is looked upon as a particularly heinous crime. Most of the documentation of the trials was done by clerks working feverously with quill and ink. Pirates were and are known for the viciousness of the crimes they commit. For them, it is not enough to steal the valuables from the boats to seize, they didn’t consider their attack complete until they had brutalized their victims. Piracy in that period included aggravated armed robbery, assault, murder, rape, and kidnapping at sea. It was a growing menace, and its presence at so close to colonial borders demanded and received the full attention of local authorities.

During five weeks in the fall of 1718, Charleston’s citizens observed thirteen trials involving fifty-eight men charged with piracy. Piracy was and is looked upon as a particularly heinous crime. Most of the documentation of the trials was done by clerks working feverously with quill and ink. Pirates were and are known for the viciousness of the crimes they commit. For them, it is not enough to steal the valuables from the boats to seize, they didn’t consider their attack complete until they had brutalized their victims. Piracy in that period included aggravated armed robbery, assault, murder, rape, and kidnapping at sea. It was a growing menace, and its presence at so close to colonial borders demanded and received the full attention of local authorities.

Between 1716 and 1718, several pirate ships frequently disrupted the maritime traffic entering and leaving Charleston’s port. These incidents significantly halted South  Carolina’s crucial sea trade. It was a serious matter and demanded serious repercussions. The pirate incursions were far more than mere nuisances or disruptions to trade. The fact was that they posed a real danger to the lives of many and threatened the political and economic foundations of the young colony. Unfortunately, with no local newspaper in Charleston until January 1732, there are no detailed accounts of the pirate activities of the 1710s. Finally, the provincial government of South Carolina, located in Charleston, engaged in discussions and formulated a collective response to the pirate threats of 1717 and 1718, but the particulars of their actions have mostly been lost to history. Consequently, we lack sufficient resources to fully narrate South Carolina’s brush with what our legislature once termed the “Pirates of the Bahamas.” Major Stede Bonnet’s crew consisted of Alexander Amand/Annand (from British Jamaica), Job ‘Bayley’ Baily (from London), Samuel Booth (from Charles Town), Robert Boyd (from Bath Town), Thomas Carman

Carolina’s crucial sea trade. It was a serious matter and demanded serious repercussions. The pirate incursions were far more than mere nuisances or disruptions to trade. The fact was that they posed a real danger to the lives of many and threatened the political and economic foundations of the young colony. Unfortunately, with no local newspaper in Charleston until January 1732, there are no detailed accounts of the pirate activities of the 1710s. Finally, the provincial government of South Carolina, located in Charleston, engaged in discussions and formulated a collective response to the pirate threats of 1717 and 1718, but the particulars of their actions have mostly been lost to history. Consequently, we lack sufficient resources to fully narrate South Carolina’s brush with what our legislature once termed the “Pirates of the Bahamas.” Major Stede Bonnet’s crew consisted of Alexander Amand/Annand (from British Jamaica), Job ‘Bayley’ Baily (from London), Samuel Booth (from Charles Town), Robert Boyd (from Bath Town), Thomas Carman  (from Maidstone, Kent), and George Dunkin (from Glasgow), to name a few, were considered particularly vicious, and their punishments would need to be vicious as well.

(from Maidstone, Kent), and George Dunkin (from Glasgow), to name a few, were considered particularly vicious, and their punishments would need to be vicious as well.

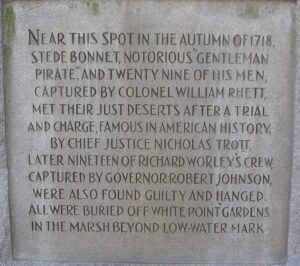

Following the trials and guilty verdicts, Major Stede Bonnet and his crew of 29 men were hanged on November 8, 1718, at White Point, Charleston, South Carolina. It had been decided that hanging just wasn’t bad enough for the crimes these men committed. I’m sure they thought long and hard about how they could show the same viciousness to these men, that they had shown to their victims. Finally, they came up with the perfect final punishment. Following their hanging, these men were buried in the marsh below the low watermark.

Leave a Reply