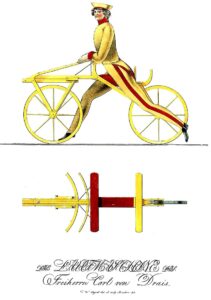

Pierre Lallement was living in Nancy, France when he saw someone on a Dandy Horse, which is basically a strider bike. That bike is powered when the rider runs while straddling a bicycle seat. It’s a great was to teach a child how to balance on a bicycle before they are quite ready for a full two-wheeler. Lallement thought this was very cool, but as a mechanic, he thought he could vastly improve on that design.

Pierre Lallement was living in Nancy, France when he saw someone on a Dandy Horse, which is basically a strider bike. That bike is powered when the rider runs while straddling a bicycle seat. It’s a great was to teach a child how to balance on a bicycle before they are quite ready for a full two-wheeler. Lallement thought this was very cool, but as a mechanic, he thought he could vastly improve on that design.

While living in Nancy and working as a carriage builder, Lallement first encountered a dandy horse. He began to picture a similar device, but with some specific improvements. His ideas made his invention quite different that the dandy horse. Lallement added a transmission and pedals, which allowed for a more efficient, faster, and definitely a more dignified mode of transportation. Lallement began working with Pierre Marchaux, a fellow carriage maker, to fine tune his idea, but it is Lallement who is credited with developing the first functional bicycle prototype. Then, due to a dispute involving himself,  Marchaux and his son, and the Olivier brothers—who later became Marchaux’s partners, Lallement found himself ostracized from the nascent bicycle industry in France.

Marchaux and his son, and the Olivier brothers—who later became Marchaux’s partners, Lallement found himself ostracized from the nascent bicycle industry in France.

Undeterred, Lallement continued his work. In 1865, he immigrated to America with his plans and parts for the invention that existed only in his head at that time. Upon arriving in the United States, Lallement settled in Ansonia, Connecticut. He demonstrated his invention to the locals, with one reportedly fleeing in terror at the sight of a “devil on wheels.” Lallement eventually found an investor, James Carroll, who supported his projects. On November 20, 1866, Lallement applied for and received the first U.S. patent for a pedal-driven bicycle. It must have felt like a amazing achievement for the man who came up with the idea and then was cheated out of the acknowledgement for its invention. While Lallement built and patented the first bicycle in the country, he was once again cheated, not by a person, but rather by circumstances. As a result, he gained little reward or

acknowledgment for introducing an invention that would quickly become widespread.

acknowledgment for introducing an invention that would quickly become widespread.

This time when he was cheated, it was due to insufficient funds to build a factory. For that reason, he sold his patent rights in 1868 and went back to France. There, the bicycle, popularized by Michaux, sparked a “bicycle craze” that swept through Europe. Albert Pope, who obtained the patent in 1876, amassed a fortune from producing the Columbia bicycle and became a prominent cycling proponent, establishing the League of American Wheelmen in 1880. Regrettably, Lallement died unrecognized in Boston in 1881, and only a century later did historians acknowledge his crucial role in the invention of the bicycle.

Leave a Reply