The London Beer Flood occurred as a result of an accident at Meux and Company’s Horse Shoe Brewery in London on October 17, 1814. The disaster unfolded when a 22-foot-tall wooden vat containing fermenting porter ruptured. The force of the escaping beer dislodged the valve of another vat and caused the destruction of several large barrels, releasing a total of between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons (approximately 154,000 to 388,000 US gallons) of beer.

The London Beer Flood occurred as a result of an accident at Meux and Company’s Horse Shoe Brewery in London on October 17, 1814. The disaster unfolded when a 22-foot-tall wooden vat containing fermenting porter ruptured. The force of the escaping beer dislodged the valve of another vat and caused the destruction of several large barrels, releasing a total of between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons (approximately 154,000 to 388,000 US gallons) of beer.

The wave of porter demolished the brewery’s rear wall and flooded the Saint Giles rookery, a slum area. Eight individuals died, including five mourners attending a wake for a two-year-old boy being held by an Irish family. The coroner’s inquest concluded that the eight died “casually, accidentally and by misfortune.” The brewery nearly faced bankruptcy due to the incident but was saved by a tax rebate from HM Excise on the beer lost. Following the disaster, the brewing industry moved away from using large wooden vats. In 1921, the brewery relocated, and the Dominion Theatre now stands in its place. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961.

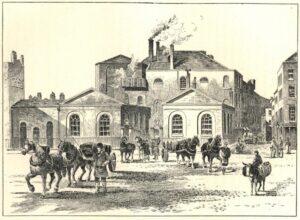

In the early 19th century, Meux Brewery was one of London’s two largest breweries, alongside Whitbread. Sir Henry Meux acquired the Horse Shoe Brewery in 1809, located at the intersection of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street. His father, Sir Richard Meux, had earlier been a co-owner of the Griffin Brewery on Liquor-Pond Street, now known as Clerkenwell Road, where he built London’s largest vat, with a capacity of 20,000 imperial barrels. Henry Meux followed in his father’s footsteps by constructing a large vat, a wooden vessel standing 22 feet high and capable of holding 18,000 imperial barrels. To reinforce the vat, eighty long tons of iron hoops were utilized. Meux exclusively brewed porter, a dark beer originating from London and highly favored as the capital’s most popular alcoholic beverage. In the year leading up to July 1812, Meux and Company produced 102,493 imperial barrels. The porter was aged in these large vessels for several months, and up to a year for the highest quality brews.

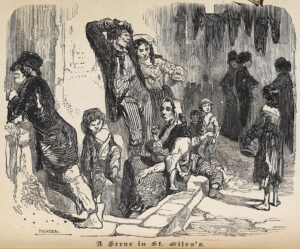

Behind the brewery lay New Street, a small dead-end road connecting to Dyott Street, situated within the Saint Giles rookery. Spanning eight acres, the rookery was a constantly deteriorating slum teetering on the brink of social and economic collapse, as noted by Richard Kirkland, a professor of Irish literature. Thomas Beames, a preacher at Westminster St James and the author of “The Rookeries of London: Past, Present and Prospective” (1852), referred to the Saint Giles rookery as a gathering place for society’s outcasts. This area also served as the muse for William Hogarth’s 1751 artwork, “Gin Lane.”

Around 4:30pm on October 17, 1814, George Crick, the storehouse clerk at Meux’s Brewery, noticed that one of the iron bands weighing 700 pounds had slipped off a vat. The vessel, standing 22 feet tall, was nearly full, containing 3,555 imperial barrels of ten-month-old porter, filled to within four inches from the top. Since such slippages occurred two or three times annually, Crick was not alarmed. He reported the issue to his supervisor, who assured him it would cause no harm. Crick was instructed to write a note to Mr Young, a brewery partner, to address the repair later.

An hour after a hoop detached, Crick stood thirty feet from the vat, note in hand for Mr Young, when suddenly, the vat burst without warning. The released liquid’s force dislodged a stopcock from an adjacent vat, causing it to release its contents; several hogsheads of porter were lost, contributing to the deluge. An estimated 128,000 to 323,000 imperial gallons were spilled. The brewery’s rear wall, 25 feet high and two and a half bricks thick, was demolished by the force. Bricks from the wall were propelled upwards, landing on the roofs of houses along Great Russell Street.

A 15-foot-high wave of porter crashed into New Street, demolishing two houses and severely damaging two others. In one of the destroyed homes, four-year-old Hannah Bamfield was having tea with her mother and another child when the beer wave swept the mother and the other child into the street, resulting in Hannah’s death. At the second house, a wake for a two-year-old boy was in progress; the boy’s mother, Anne Saville, and four mourners perished. Eleanor Cooper, a 14-year-old servant at the Tavistock Arms on Great Russell Street, was killed by a collapsing brewery wall while she was washing pots. Another victim, Sarah Bates, was found deceased in a different house on New Street. The surrounding land, being flat and poorly drained, allowed the beer to flood into cellars, forcing inhabitants to climb onto furniture to escape drowning. Everyone at the brewery survived, though three workers were rescued from the debris; the superintendent and one worker were taken to Middlesex Hospital with three others.

Rumors began to emerge of hundreds gathering to collect the beer, followed by widespread drunkenness, and a fatality due to alcohol poisoning days later. However, brewing historian Martyn Cornell insists that contemporary newspapers did not mention such chaos or the subsequent death; rather, they depicted the crowds as orderly. Cornell notes that the prevalent press at the time harbored an aversion to the immigrant Irish community in Saint Giles, suggesting that any misconduct would have been reported.

The vicinity behind the brewery revealed a “scene of desolation [that] presents a most awful and terrific appearance, akin to what one might expect from fire or earthquake.” Brewery watchmen charged onlookers to see the remnants of the shattered beer vats, attracting several hundred viewers. Those mourners who perished in the cellar received their own vigil at The Ship public house on Bainbridge Street. Meanwhile, the other victims were displayed by their families in a nearby yard, drawing public attention and financial contributions for their burials. Broader fundraising efforts were also initiated for the affected families.

The coroner’s inquest was held at the Workhouse of the Saint Giles parish on October 19, 1814; George Hodgson, the coroner for Middlesex, oversaw proceedings. The details of the victims were read out as: Eleanor Cooper, age 14; Mary Mulvey, age 30; Thomas Murry, age 3 (Mary Mulvey’s son); Hannah Bamfield, age 4 years 4 months; Sarah Bates, age 3 years 5 months; Ann Saville, age 60; Elizabeth Smith, age 27; and Catherine Butler, age 65.

Hodgson led the jurors to the event’s location, where they observed the brewery and the deceased prior to gathering witness testimony. The initial testimony came from George Crick, who witnessed the entire incident; his brother was among the injured at the brewery. Crick noted that the vat hoops would fail a few times annually, yet this had not previously led to any incidents. Testimonies were also presented by Richard Hawse, the proprietor of the Tavistock Arms, who lost a barmaid in the tragedy, among others. The jury concluded that the eight victims died “casually, accidentally, and by misfortune”. When the coroner’s inquest concluded with a verdict of an act of God, Meux and Company were not required to pay compensation. However, the disaster, including the lost porter, the damaged buildings, and the vat replacement, cost the company £23,000. Following a private petition to Parliament, they received approximately £7,250 from HM Excise, which prevented their bankruptcy. The Horse Shoe Brewery resumed operations shortly thereafter but ceased in 1921 when Meux

transferred their production to the Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, acquired in 1914. At closure, the brewery spanned 103,000 square feet. It was demolished the subsequent year, and the Dominion Theatre was constructed on its location. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961. Following the accident, the brewing industry gradually replaced large wooden tanks with lined concrete vessels.

transferred their production to the Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, acquired in 1914. At closure, the brewery spanned 103,000 square feet. It was demolished the subsequent year, and the Dominion Theatre was constructed on its location. Meux and Company was liquidated in 1961. Following the accident, the brewing industry gradually replaced large wooden tanks with lined concrete vessels.

Leave a Reply