Winter counts, known to the Lakota Sioux as waníyetu wówapi or waníyetu iyáwapi, are pictorial calendars, but not in the traditional sense. For the Native Americans, they were really more a historical record of each year, as it went along. They were tribal records and events that were recorded on buffalo skins. The Blackfeet, Mandan, Kiowa, Lakota, and other Plains tribes used winter counts extensively. There are approximately one hundred winter counts in existence, many of which are duplicates.

Winter counts, known to the Lakota Sioux as waníyetu wówapi or waníyetu iyáwapi, are pictorial calendars, but not in the traditional sense. For the Native Americans, they were really more a historical record of each year, as it went along. They were tribal records and events that were recorded on buffalo skins. The Blackfeet, Mandan, Kiowa, Lakota, and other Plains tribes used winter counts extensively. There are approximately one hundred winter counts in existence, many of which are duplicates.

Winter counts were traditionally painted on bison hides. They displayed a sequence of years by depicting their most remarkable events. Waniyetu translates to ‘winter’ while ‘wowapi’ refers to “anything that is marked and can be read or counted.” Most winter counts have a single pictograph symbolizing each year, based on the most memorable event of that year, which would indicate that the winter counts would be painted at the end of the current year or the beginning of the coming year. For the Lakota people, years ran from first snowfall to first snowfall, making the Lakota years a variable timeframe. If the snow came early, the year might be longer, and if the snow came late, the year might be shorter. Kiowa winter counts usually feature two marks per year…one for winter and one marking the summer Sun Dance. The glyphs representing significant events would be used as a reference that could be consulted regarding the order of the years.

Similar to other traditions among the Indigenous nations of North America, winter counts used as mnemonic records to structure fuller accounts of history that would be passed on orally. (Mnemonic is a device such as a pattern of letters, ideas, or associations that assists in remembering something, for example Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain for the colors of the spectrum (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet)). The Indigenous peoples of North America had many ways of recording history during the pre-contact period, and they did not depend on alphabetic writing. Since they didn’t use written records, oral tradition became an extremely important aspect of Indigenous lifeways. In fact, it was the main way that knowledge was passed from generation to generation. Oftentimes, pictorial or other mnemonic devices were used as guideposts for  these practices. This is significantly present in the Sioux cultural tradition of oral history preservation through the form of winter counts. Located in the Northern Great Plains, Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota people physically recorded yearly events on various materials before and continuing past the point of contact with settlers.

these practices. This is significantly present in the Sioux cultural tradition of oral history preservation through the form of winter counts. Located in the Northern Great Plains, Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota people physically recorded yearly events on various materials before and continuing past the point of contact with settlers.

While winter counts reveal the year number when studied and compared to other sources, the similarities between some winter counts also demonstrate inter-band relations. Some bands in the Great Plains region had close ties through alliances, their winter counts could often be very similar. Scholars have noted that the Lone Dog, The Flame, The Swan, and Major Bush winter counts are so similar for this reason. These bands lived close by and often interacted with each other, so it stands to reason that many of their experiences would be the same, or similar.

Lakota winter counts reveal deeply rooted historical ties with European traders that predated the Lewis and Clark Expedition. These reveal a period that foreshadowed the extreme marginalization and oppression of Indigenous People in America. This period exemplifies a history that highlights the relationships between bands and settlers, along with their political social dynamics. By the late 1870 to early 1880s, copies winter counts, such as those by American Horse, Cloud Shield, Battiste, were commissioned by European collectors as Indigenous ethnographic objects.

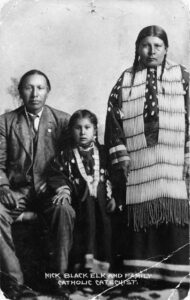

Traditionally, each of the bands would choose a single keeper of the winter count. These keepers were always men, until the twentieth century. They would consult with tribal elders to reach a consensus for choosing a name for the year. The keeper was then allowed to choose his successor in recording the count. That person was often a family member. In many cases, winter counts were buried with their keepers when they died, so that many winter counts were recreated copies done by an apprentice or collector, which is why so few of the original winter counts are available today.

Buffalo hides were used for winter counts until the late 19th century, at which time buffalo became scarce. Then, keepers resorted to using muslin, linen, or paper. Generally, the annual pictographs began on either the left or right side of the drawing surface. From there, they could be run in lines, spirals, or serpentine patterns. Epidemic diseases were commonly depicted in winter counts, a fact that provided some historical record of the effects of illnesses among tribes. By studying written accounts from fur traders, missionaries, and military  personnel from a winter count’s time and place of origin, scholars have been able to gain a broader understanding of the effects of epidemics.

personnel from a winter count’s time and place of origin, scholars have been able to gain a broader understanding of the effects of epidemics.

These days, winter counts serve as valuable historical sources for those studying the history of the Great Plains peoples, as well as their experiences with colonialism. During the nineteenth century, settler colonialism led to the marginalization of many groups of Sioux people. This happened because many Indigenous groups were not literate in a European sense, so their story was largely omitted from an American history that was predominantly dependent on written source material. That is very unfortunate indeed.

Leave a Reply