Being in the fur trade, especially back in the 1800s was no picnic. While the trapper was the one with the traps and the guns, that doesn’t mean that the wild animals couldn’t get the better of them from time to time. In addition, the hardships endured by even the most resilient of trappers, such as being alone in the wilderness and in constant danger of conflict with both wild animals and men, are beyond our ability to comprehend. Most perished in the quiet of remote areas, their names now lost, the valor of their final struggles unrecorded. Only the archives of the major fur companies offer scant references to such events deemed significant enough to document.

Being in the fur trade, especially back in the 1800s was no picnic. While the trapper was the one with the traps and the guns, that doesn’t mean that the wild animals couldn’t get the better of them from time to time. In addition, the hardships endured by even the most resilient of trappers, such as being alone in the wilderness and in constant danger of conflict with both wild animals and men, are beyond our ability to comprehend. Most perished in the quiet of remote areas, their names now lost, the valor of their final struggles unrecorded. Only the archives of the major fur companies offer scant references to such events deemed significant enough to document.

These events typically took place in the great mountains, where trappers held rendezvous and spent the majority of their lives. The catastrophic Battle of Pierre’s Hole, the valiant exploration of Utah, and the initial advance into California are all laden with dramatic episodes. However, these incidents occurred too far to the west to be included in the scope of this current work.

In the initial years of exploration, with beaver trapping along the streams, the Great Plains served primarily as a thoroughfare from civilized regions to the more lucrative mountainous areas beyond. Travelers, whether alone or in groups, journeyed up the Missouri River by boat or trekked along the Platte River valley on foot, aiming for the distant mountain ranges. Undoubtedly, they experienced considerable hardship, adventure, and conflicts with Native Americans along those extensive prairie stretches, yet these events were deemed too mundane to merit inclusion in the fur companies’ matter-of-fact records.

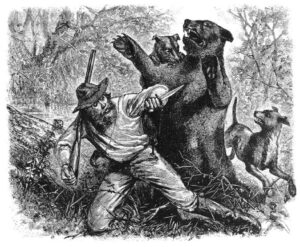

One man had a harrowing experience, and somehow it was deemed important to make it into the annals of history. The remarkable survival of Hugh Glass is a testament to the resilience and fortitude of these frontiersmen. Glass was part of Andrew Henry’s group on an expedition to the Yellowstone River. While hunting near the Grand River, a grizzly bear charged from the brush, knocked him down, ripped a chunk of flesh from him, and fed it to her cubs. Glass attempted to flee, but the bear quickly attacked again, biting his shoulder and causing severe injuries to his hands and arms. At that moment, his fellow hunters arrived and killed the bear. Glass was grievously injured and barely alive. He was not expected to live. In the hostile territory of the Native Americans, the group had to move on swiftly. Eventually, Major Henry persuaded two men to stay with Glass by offering a reward, while the rest continued on. The two were John S Fitzgerald and a man named “Bridges,” who some say was a young James “Jim” Bridger, the same Jim Bridger who would become a renowned trapper. That has not been confirmed. They stayed with Glass for five days, but losing hope in his recovery and seeing no signs of imminent death, they departed, taking his rifle and gear. Upon rejoining their group, they reported Glass as deceased.

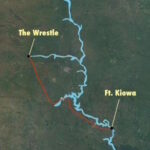

Yet, Glass was still alive. Regaining consciousness, he dragged himself to a nearby spring. There, he found wild cherries and buffalo berries, which sustained him as he gradually regained his strength. Eventually, he embarked on a solitary trek to his destination, Fort Kiowa, on the Missouri River, 100 miles distant. He began his journey with barely enough strength to move, without provisions or any means to obtain them, in a land where any wandering Indian could easily overpower him. However, his will to live and a burgeoning desire for vengeance against those who had abandoned him spurred him on. Luck appeared to be on his side. He stumbled upon wolves attacking a buffalo calf. After the wolves had killed it, he scared them off and took the meat, consuming it as best as he could without a knife or fire. Carrying as much as possible, he continued determinedly and, despite immense suffering and difficulties, ultimately arrived at Fort Kiowa, located in what is now South Dakota.

Glass returned to the field before his wounds had fully healed. Heading east with a group of trappers along the Missouri River, they approached the Mandan villages, and he chose to traverse a bend in the river on foot. That turned out to be a wise move when Arikara Indians attacked the boats, killing everyone aboard. Glass, who was too weak to fight, narrowly escaped and was rescued by friendly Mandan Indians who took him to Tilton’s Fort. Driven by a desire for revenge against the two who had abandoned him in the mountains, he left Tilton’s that very night. So, Glass set out, braving the wilderness alone. He traveled for 38 days through territory hostile with Indian tribes, until he arrived at Fort Henry near the confluence of the Big Horn River in what is now Montana. There, he learned that the men he was after had headed east. Undeterred, he seized an opportunity to deliver a dispatch to Fort Atkinson, Nebraska.

Then, after completely healing from his injuries, Glass resumed his quest to locate Fitzgerald and “Bridges.” He made his way to Fort Henry on the Yellowstone River, only to discover it abandoned. A left-behind note revealed that Andrew Henry and his group had moved to a new encampment at the Bighorn River’s mouth. Upon reaching this location, Glass encountered “Bridges” and seemingly pardoned him due to his young age, before rejoining Ashley’s company.

Glass eventually discovered that Fitzgerald had enlisted in the army and was posted at Fort Atkinson, now in Nebraska. Glass chose to spare Fitzgerald’s life, knowing that the army captain would execute him for murdering a fellow soldier. Nevertheless, the captain demanded Fitzgerald return the rifle he had taken from Glass. Upon returning it, Glass cautioned Fitzgerald to never desert the army, or he would face death at Glass’s hands. A later account by Glass’s companion, George C Yount, which wasn’t published until 1923, revealed that Glass received $300 in restitution. I’m sure Fitzgerald felt he got off easy and had no plans to leave the army.

In early 1833, Glass, along with fellow trappers Edward Rose and Hilain Menard, was killed on the Yellowstone River during an Arikara attack. A monument honoring Glass stands near the location of his mauling on the southern bank of what is now Shadehill Reservoir in Perkins County, South Dakota, at the confluence of the Grand River. The adjacent Hugh Glass Lakeside Use Area also offers a state-maintained campground and picnic site at no cost.

In early 1833, Glass, along with fellow trappers Edward Rose and Hilain Menard, was killed on the Yellowstone River during an Arikara attack. A monument honoring Glass stands near the location of his mauling on the southern bank of what is now Shadehill Reservoir in Perkins County, South Dakota, at the confluence of the Grand River. The adjacent Hugh Glass Lakeside Use Area also offers a state-maintained campground and picnic site at no cost.

Leave a Reply