The initiative to send a relief army to support Antwerp did not begin with Winston Churchill, but with Lord Kitchener and the French Government. Churchill was not involved or consulted about the plans until they were well underway, with significant troop movements already in progress or planned. Deciding that he should be brought into the loop, Churchill was summoned to a midnight meeting at Lord Kitchener’s residence on October 2, 1914. It was during this meeting that he fully grasped the progress of the plans to send a relief army to Antwerp, a coordination between Lord Kitchener and the French Government. He learned as well that no definitive commitments had been made to the Belgian Government. On that same afternoon, the Belgian Government had resolved to evacuate Antwerp, pull back the field army from the fort, and effectively abandon the city’s defense.

The initiative to send a relief army to support Antwerp did not begin with Winston Churchill, but with Lord Kitchener and the French Government. Churchill was not involved or consulted about the plans until they were well underway, with significant troop movements already in progress or planned. Deciding that he should be brought into the loop, Churchill was summoned to a midnight meeting at Lord Kitchener’s residence on October 2, 1914. It was during this meeting that he fully grasped the progress of the plans to send a relief army to Antwerp, a coordination between Lord Kitchener and the French Government. He learned as well that no definitive commitments had been made to the Belgian Government. On that same afternoon, the Belgian Government had resolved to evacuate Antwerp, pull back the field army from the fort, and effectively abandon the city’s defense.

The men were deeply troubled by the Belgian Government’s plan. It appeared that just as help was within reach, everything might be sacrificed for a mere three or four days of further resistance. Under these conditions, Churchill proposed to immediately travel to Antwerp to inform the Belgian Government of the ongoing efforts, assess the situation firsthand, and explore how the defense could be extended until a relief force was ready. The others agreed to Churchill’s proposal, and he promptly made his way across the Channel.

The next day, after discussions with the Belgian Government and British Staff officers in Antwerp overseeing the operations, Churchill presented a cautious telegraphic proposal. He avoided any declarations on behalf of the British Government that might encourage the Belgians to hold out for support he couldn’t guaranteed.

Churchill’s proposal was concise and transmitted via telegram. It stated: “The Belgians were to continue the resistance to the utmost limit of their power. The British and French Governments were to say within three days definitely whether they could send a relieving force or not, and what the dimensions of that force would be.

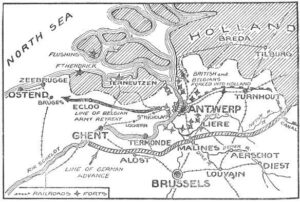

In the event of their not being able to send a relieving force the British Government were to send in any case to Ghent and other points on the line of retreat British troops sufficient to insure the safe retirement of the Belgian field army, so that the Belgian  field army would not be compromised through continuing the resistance on the Antwerp fortress line.

field army would not be compromised through continuing the resistance on the Antwerp fortress line.

Incidentally, we were to aid and encourage the defense of Antwerp by the sending of naval guns, naval brigades, and any other minor measures likely to enable the defenders to hold out the necessary number of days.”

The proposal was contingent upon approval from both parties. It remained unsettled until it received the acceptance of both governments. Upon agreement, Churchill received a telegraph announcing the dispatch of a relief army, including its size and structure, which I was to communicate to the Belgians. Churchill was instructed to do all in his power to sustain the defense in the interim, which he did, disregarding any potential repercussions.

Churchill chose not to recount the well-known military events, but he believed it would be erroneous to view Lord Kitchener’s attempts to relieve Antwerp, in which Churchill had a significant but secondary role, as a venture that resulted solely in adversity.

Churchill believed that military history would deem the outcomes highly favorable to the Western Allies. The significant battle that began on the Aisne was extending daily towards the sea. Sir John French’s forces were assembling and commencing the Battle of Armentières, which led to the pivotal Battle of Ypres, amid an ever-changing situation.

The prolonged defense of Antwerp, even by just a few days, detained substantial German forces near the fortress. The sudden and audacious deployment of a new British division and a British cavalry division at Ghent, among other places, perplexed the cautious German command, causing them to anticipate the arrival of a large force from the sea.

Regardless, their advance was tentative, faced with only weak opposition, and Churchill was convinced that history would confirm, certainly in his view and that of many esteemed military officers of the time, that the

entirety of this operation…the movement of the British and associated French troops…though it failed to save Antwerp, resulted in the great battle being fought along the Yser, rather than twenty or thirty miles to the south, and if that was the case, then the losses sustained by the naval division, fortunately not severe in terms of lives, will undoubtedly have been justified for the greater good.

entirety of this operation…the movement of the British and associated French troops…though it failed to save Antwerp, resulted in the great battle being fought along the Yser, rather than twenty or thirty miles to the south, and if that was the case, then the losses sustained by the naval division, fortunately not severe in terms of lives, will undoubtedly have been justified for the greater good.

Leave a Reply