With the election of Thomas Jefferson as third president, on February 17, 1801, came the first peaceful transfer of power from one political party to another in the United States. Nevertheless, the election was an unusual one. By this time, Jefferson had helped to draft the Declaration of Independence, had served in two Continental Congresses, as minister to France, as secretary of state under George Washington and as John Adams’ vice president. These credentials probably made him the best person for the job in the entire world.

With the election of Thomas Jefferson as third president, on February 17, 1801, came the first peaceful transfer of power from one political party to another in the United States. Nevertheless, the election was an unusual one. By this time, Jefferson had helped to draft the Declaration of Independence, had served in two Continental Congresses, as minister to France, as secretary of state under George Washington and as John Adams’ vice president. These credentials probably made him the best person for the job in the entire world.

While it was obvious that Jefferson was the best man for the job, vicious partisan warfare was the name of the game during the campaign of 1800 between Democratic-Republicans Jefferson and Aaron Burr and Federalists John Adams, Charles C Pinckney and John Jay. The ongoing battle raged between Democratic-Republican supporters of the French, who were involved in their own bloody revolution, and the pro-British Federalists who wanted to implement English-style policies in American government. The Federalists hated the French revolutionaries because of their overzealous use of the guillotine and, as a result, were less forgiving in their foreign policy toward the French. They pushed for a strong centralized government, a standing military, and financial support of emerging industries.

Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans, on the other hand, preferred limited government, complete and absolute states’ rights and a primarily agricultural economy. They feared that Federalists would abandon revolutionary ideals and revert to the English monarchical tradition. When Jefferson was secretary of state under Washington, he opposed Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton’s proposal to increase military expenditures and resigned when Washington supported the leading Federalist’s plan for a national bank.

A bloodless, but ugly campaign ensued, in which candidates and influential supporters on both sides used the press, often anonymously, as a forum to fire slanderous volleys at each other. It sounds a lot like some of our election campaigns of today. Then came the laborious and confusing process of voting, that began in April 1800. Individual states scheduled elections at different times, which I think further confuses the situation, and although Jefferson and Burr ran on the same ticket, as president and vice president respectively, the Constitution still demanded votes for each individual to be counted separately. As a result, by the end of January 1801, Jefferson and Burr emerged tied at 73 electoral votes apiece. Adams came in third at 65 votes. While that left Adams out, it left a tie for Jefferson and Burr. The result created a big problem.

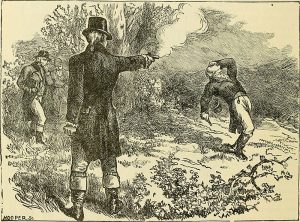

The resulting tie sent the final vote to the House of Representatives. That would not make for an easy decision e ither. A number of those in the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives insisted on following the Constitution’s flawed rules and refused to elect Jefferson and Burr together on the same ticket. The highly influential Federalist Alexander Hamilton, who mistrusted Jefferson, but hated Burr more, persuaded the House to vote against Burr, whom he called the most unfit man for the office of president. Of course, that cause a hatred between Hamilton and Burr that led Burr to challenge Hamilton to a duel in 1804. Burr won the duel when he killed Hamilton. Two weeks before the scheduled inauguration, Jefferson emerged victorious, and Burr was confirmed as his vice president. It was the first of only two times the presidency has been decided by the House of Representatives.

ither. A number of those in the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives insisted on following the Constitution’s flawed rules and refused to elect Jefferson and Burr together on the same ticket. The highly influential Federalist Alexander Hamilton, who mistrusted Jefferson, but hated Burr more, persuaded the House to vote against Burr, whom he called the most unfit man for the office of president. Of course, that cause a hatred between Hamilton and Burr that led Burr to challenge Hamilton to a duel in 1804. Burr won the duel when he killed Hamilton. Two weeks before the scheduled inauguration, Jefferson emerged victorious, and Burr was confirmed as his vice president. It was the first of only two times the presidency has been decided by the House of Representatives.

Leave a Reply