I had never heard the expression, “war sand” before, but when I think about it, the presence of it makes perfect sense. It would be impossible to have any kind of a battle and not leave behind spent bullets, as well as bits of shrapnel from bombs littering the battlefield. In the case of the D-Day Battle, there were more that 5,000 tons of bombs that littered the beaches of Normandy. The beaches were literal chaos, and it was all they could do to rescue the wounded, recover the bodies, and remove the equipment, much less save bits of metal and spent bullets left behind. On D-Day, more than 5,000 tons of bombs were dropped by the Allies on the Axis powers as part of the prelude to the Normandy landings…and then there was the bullets and such that hit the beaches during the battle.

I had never heard the expression, “war sand” before, but when I think about it, the presence of it makes perfect sense. It would be impossible to have any kind of a battle and not leave behind spent bullets, as well as bits of shrapnel from bombs littering the battlefield. In the case of the D-Day Battle, there were more that 5,000 tons of bombs that littered the beaches of Normandy. The beaches were literal chaos, and it was all they could do to rescue the wounded, recover the bodies, and remove the equipment, much less save bits of metal and spent bullets left behind. On D-Day, more than 5,000 tons of bombs were dropped by the Allies on the Axis powers as part of the prelude to the Normandy landings…and then there was the bullets and such that hit the beaches during the battle.

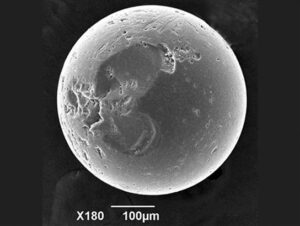

These days, scientists estimate that 4% of the Normandy beaches are made up of shrapnel from the D-Day Landings. They have studied the sand on the beaches of Normandy, and they’ve found microscopic bits of smoothed-down shrapnel from the landings. The sand on the Normandy beaches is known as “war sand,” which is defined as “sand that is a result from wartime operations.” I had heard of beaches that are made of glass that has been rubbed smooth by the water against the ground, but I hadn’t ever thought about the water being able to smooth the sharp bits of shrapnel to make them smooth. Nevertheless, the beaches of Normandy are  covered in a fine dust created from particles deposited there during or right before the D-Day operations of World War II. The grains are hidden among the beaches of the Normandy. It makes me wonder how many other beaches have shrapnel and bullets as a secret part of their makeup.

covered in a fine dust created from particles deposited there during or right before the D-Day operations of World War II. The grains are hidden among the beaches of the Normandy. It makes me wonder how many other beaches have shrapnel and bullets as a secret part of their makeup.

Earle McBride, a geologist from the University of Texas at Austin, figures the sands shrapnel level at 4%. That doesn’t seem like much, but considering the years since D-Day, and the number of people who have walked those beaches, possibly looking for closure concerning lost loved ones, 4% is quite a bit. One might wonder how he could have come to that conclusion, but apparently the sand-sized fragments of steel are magnetic, making them easily discernible under a microscope. Of course, there are still relics from the battle. The artificial landscape of eroded machinery is still detectable using special instruments in the coastal dunes.

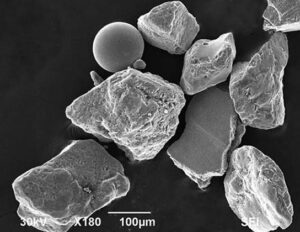

The shrapnel content of the beaches will eventually disappear. It is estimated that at the present rate of deterioration, the magnetic particles will probably be wiped from the sands in another 100 years. The shrapnel is subject to waves, storms, and rust, which will wipe these spherical magnetic shards from the coasts.  Strangely, Earle McBride didn’t set out to find these shards, but a visit to Omaha Beach in 1988 resulted in the discovery of these tiny remnants of shrapnel. I wonder how he noticed the shrapnel. Oddly, the shards were collected 20 years ago and only analyzed recently. Why did it take so long to examine them? Of course, I have answered my own question. While he may have known what he had, it is possible that he really didn’t or at least didn’t know the significance of what he had. He might have simply collected the sand as a keepsake of his visit. Nevertheless, upon examination, the samples revealed that the jagged-edged grains had a metallic sheen and a rust-colored coating. The angular grains proved to be magnetic…they proved to be shrapnel from that long ago battle.

Strangely, Earle McBride didn’t set out to find these shards, but a visit to Omaha Beach in 1988 resulted in the discovery of these tiny remnants of shrapnel. I wonder how he noticed the shrapnel. Oddly, the shards were collected 20 years ago and only analyzed recently. Why did it take so long to examine them? Of course, I have answered my own question. While he may have known what he had, it is possible that he really didn’t or at least didn’t know the significance of what he had. He might have simply collected the sand as a keepsake of his visit. Nevertheless, upon examination, the samples revealed that the jagged-edged grains had a metallic sheen and a rust-colored coating. The angular grains proved to be magnetic…they proved to be shrapnel from that long ago battle.

Leave a Reply