Monthly Archives: December 2023

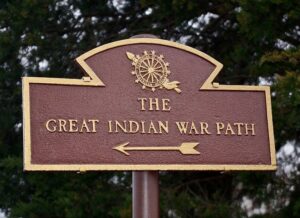

Knowing that a Native American trail called The Great Indian Warpath, also known as the Great Indian War and Trading Path, or the Seneca Trail, ran through the Great Appalachian Valley and the Appalachian Mountains, makes me wonder how many other major trails started out as or connect to smaller trails that had entirely different uses. The Great Indian Warpath was a network of ancient Indian routes with many branches. It crossed the Appalachian Trail in a number of places across several states, including New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Tennessee, and Alabama. The Great Indian Warpath was a major north-south route of travel since prehistoric times. Parts of the trail are thought to have been used as many as 2,500 years ago when Indian traders from as far away as the Great Lakes, Rocky Mountains, and Mexico traveled parts of the trail. Various northeastern Indian tribes were known to have traded and made war along the trail, including the Catawba, numerous Algonquian tribes, the Cherokee, and the Iroquois Confederacy, even into more recent history, like the Old West.

Knowing that a Native American trail called The Great Indian Warpath, also known as the Great Indian War and Trading Path, or the Seneca Trail, ran through the Great Appalachian Valley and the Appalachian Mountains, makes me wonder how many other major trails started out as or connect to smaller trails that had entirely different uses. The Great Indian Warpath was a network of ancient Indian routes with many branches. It crossed the Appalachian Trail in a number of places across several states, including New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Tennessee, and Alabama. The Great Indian Warpath was a major north-south route of travel since prehistoric times. Parts of the trail are thought to have been used as many as 2,500 years ago when Indian traders from as far away as the Great Lakes, Rocky Mountains, and Mexico traveled parts of the trail. Various northeastern Indian tribes were known to have traded and made war along the trail, including the Catawba, numerous Algonquian tribes, the Cherokee, and the Iroquois Confederacy, even into more recent history, like the Old West.

Eventually the Europeans and the White citizen of America began to use the Great Indian Warpath trail, which seems a little bit strange when you think about it. Nevertheless, Europeans, Hernando de Soto and his party used the trail when they crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains in 1540. Then, by the late 1600s, British colonists were using portions of the trail regularly, as they traded with the Indians. The British traders renamed the trail, or gave it a nickname anyway. Their name for the route was created by combining its name among the northeastern Algonquian tribes, “Mishimayagat” or “Great Trail,” with that of the Shawnee and Delaware, “Athawominee” or “Path where they go armed.” The combination translated to the Great Indian Warpath. Later, hunters and settlers traveled the trail to explore Kentucky and Tennessee, which led to the first mass western migration in American history, as settlers followed the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap.

As time went on, the people left the trail at different places to go to find their dreams. Those new trails took on new names, such as the Seneca Trail, the Great Valley Road, Kanawha Trail, Wilderness Road, Catawba Trail, Unicoi Trail, and the Georgia Road. As I think about the well-known trail in the area, the Appalachian Trail, and the number of people who travel that trail every year, it makes me wonder if they have ever noticed the trails

that cross it or split off of it. I have hiked along many trails over the years, and I have seen the many trails that have crossed them. Now I wonder what pioneers might have taken those trails on their journeys to wherever it was that they were headed. It’s unlikely that I will ever know the true stores, but it is nice to think about it anyway.

that cross it or split off of it. I have hiked along many trails over the years, and I have seen the many trails that have crossed them. Now I wonder what pioneers might have taken those trails on their journeys to wherever it was that they were headed. It’s unlikely that I will ever know the true stores, but it is nice to think about it anyway.

Hijacking is usually associated with airplanes, but it is certainly not limited to airplanes, nor is it limited to any one country. One of the scariest situations for parents of school children is when their bus is hijacked. That is exactly what happened on December 1, 1988, when five armed criminals, led by Pavel Yakshiyants hijacked a LAZ-687 bus carrying around thirty pupils and one teacher from school 42 in Ordzhonikidze, Soviet Union (now Vladikavkaz in Russia).

Hijacking is usually associated with airplanes, but it is certainly not limited to airplanes, nor is it limited to any one country. One of the scariest situations for parents of school children is when their bus is hijacked. That is exactly what happened on December 1, 1988, when five armed criminals, led by Pavel Yakshiyants hijacked a LAZ-687 bus carrying around thirty pupils and one teacher from school 42 in Ordzhonikidze, Soviet Union (now Vladikavkaz in Russia).

Most countries don’t often concede to the demands of the hijackers, because it doesn’t guarantee the safety of the hostages, but in this case, the local authorities did concede to the hijackers’ demands and provided an Ilyushin Il-76 aircraft to fly the hijackers to Israel. It was a very strange situation, as hijackings go, because first of all, the hostages were released when the demands were met. Meeting the demands of the hijackers unequivocally, often results in the hostages being taken to another location, where the situation just continues to escalate. In this case, however the hijackers landed at Tel Aviv’s Ben Gurion Airport, and the hijackers surrendered to local troops and police without resistance. Then, Israel agreed to extradited to the men to the Soviet Union, where they were sentenced to prison terms. What made that very strange was that at that time Israel and the Soviet Union had no extradition treaty, because relations between the two countries were still severed. All hostages were released. The Defense Minister of Israel at the time, Yitzhak Rabin, criticized Soviet authorities for providing the hijackers with an aircraft and flying them to Israel in exchange for the release of the hostages, thereby making it Israel’s problem.

The hijacking was carried out by Pavel Levonovich Yakshiyants, Vladimir Alexandrovich Muravlev, German Lvovich Vishnyakov, Vladimir Robertovich Anastasov, and Tofiy Jafarov. Yakshiyants and Muravlev were prior convicts, while the others were first time offenders. Yakshiyants, an Armenian, was first convicted when he was 17 and sentenced to two years in prison for theft. That did little to deter him, and he was later sentenced to four years in prison for robbery. Then in 1972, he was sentenced to ten years, again for robbery, but somehow managed to be released on parle in 1979.

What had started out as a field trip, turned scary when a man approached them saying he was the driver sent to take them home. The group of 30–31 schoolchildren had just finished a field trip to a local printing plant when the hijacking occurred. Subsequently, the teacher and her pupils, aged 10 and 11, boarded the bus to find themselves the hostages of five armed people. The group was then used as a human shield and bargaining chip to make sure their demands were met. The hijackers rode to the local obkom, which is “literally the “Washington Province Party Committee” and is a derogatory term used in Russian media and speech to imply that many crucial decisions by political elites of Russia and some other post-Soviet states have been and are agreed with and/or taken in the United States.” The hijackers demanded about 2 million rubles, which is about US$3.3 million at the time, and an aircraft. The authorities agreed, but the airport of Ordzhonikidze was unable to handle the large Ilyushin Il-76 cargo aircraft that was sent. The hijackers were told that they would have free passage to airport of Mineralnye Vody, so they went there. The bus windows were curtained so that the law enforcement units could not see what was happening inside. Russia’s Alpha Group was mobilized for a possible hostage rescue. It was learned that the hijackers were planning to land in Tashkent to pick up a friend then fly to Pakistan, but changed their mind and chose Israel instead. According to Israeli Army commander Major General Amram Mitzna, the hijackers believed they would be safe in Israel because they had heard that recent Israeli elections had produced an anticommunist government. Boy, were they in for a surprise?

The Ilyushin Il-76 cargo aircraft was escorted by Israeli fighter aircraft and landed on a remote darkened runway. It was quickly surrounded by army and police vehicles and ambulances. According to an Ilyushin Il-76 crew member, the hijackers asked whether they had landed in Israel or Syria. They said that if it was Israel,  they would stay. Mitzna said that the hijackers demanded proof that they were actually in Israel. They wanted to hear Yiddish or see a Star of David. When a soldier on the runway spoke a few words in Yiddish, the hijackers left the aircraft with their hands in the air. The hostages were quickly secured and were flown back to Ordzhonikidze. Following the extradition, the ring leaders, Yakshiyants and Murlav were put on trial. In March 1989, Yakshiyants was sentenced by the Supreme Court of Russia to 15 years in prison. Murlav was sentenced to 14 years. The remaining defendants received sentences ranging from three to fourteen years. All of the hostages arrived home safely, none the worse off for their ordeal.

they would stay. Mitzna said that the hijackers demanded proof that they were actually in Israel. They wanted to hear Yiddish or see a Star of David. When a soldier on the runway spoke a few words in Yiddish, the hijackers left the aircraft with their hands in the air. The hostages were quickly secured and were flown back to Ordzhonikidze. Following the extradition, the ring leaders, Yakshiyants and Murlav were put on trial. In March 1989, Yakshiyants was sentenced by the Supreme Court of Russia to 15 years in prison. Murlav was sentenced to 14 years. The remaining defendants received sentences ranging from three to fourteen years. All of the hostages arrived home safely, none the worse off for their ordeal.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration, also known as “the Crash in the Desert” was a joint project between NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The idea was to intentionally crash a remotely controlled Boeing 720 airplane in order to acquire data and test new technologies to aid passenger and crew survival. As we all know, airplane crashes, often bring fatalities. Still, there have been a number of airplane crashes in which all or most of the plane’s occupants survived the crash. The point of “the crash in the desert” was to learn from the vent, and hopefully make a way for more people to survive the crash.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration, also known as “the Crash in the Desert” was a joint project between NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The idea was to intentionally crash a remotely controlled Boeing 720 airplane in order to acquire data and test new technologies to aid passenger and crew survival. As we all know, airplane crashes, often bring fatalities. Still, there have been a number of airplane crashes in which all or most of the plane’s occupants survived the crash. The point of “the crash in the desert” was to learn from the vent, and hopefully make a way for more people to survive the crash.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration took more than four years of preparation by NASA Ames Research Center, Langley Research Center, Dryden Flight Research Center, the FAA, and General Electric to pull off. Then, because obviously they did not have an unlimited supply of planes, they held several test runs to make sure they had the right “crash” conditions to learn the most about crashes. Finally, on December 1, 1984, the plane was actually crashed. The test went pretty much according to plan and produced a large fireball that required more than an hour to extinguish. With that in mind, a casual observer would assume that everyone would have died, but the FAA concluded that about one-quarter of the passengers would have survived!! It also determined that the antimisting kerosene test fuel did not sufficiently reduce the risk of fire. Antimisting kerosene (AMK) is “a jet fuel containing an antimisting additive. This additive, a high-molecular-weight polymer, causes the fuel to resist atomization and liquid shear forces, which also affect flow characteristics in the engine fuel system.” Finally, it determined that several changes to equipment in the passenger compartment of aircraft were needed…which is probably one of the most important findings of the demonstration. NASA also concluded that a head-up display and microwave landing system would have definitely helped the pilot more safely fly the aircraft.

On the morning of December 1, 1984, the test aircraft took off from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Once aloft, the plane made a left-hand departure and climbed to an altitude of 2,300 feet. The plane was remotely flown by NASA research pilot Fitzhugh Fulton from the NASA Dryden Remotely Controlled Vehicle Facility. All fuel tanks were filled with a total of 76,000 pounds of AMK and all engines ran from start-up to impact. The total flight time was 9 minutes on the modified Jet-A. It then began a descent-to-landing along the roughly 3.8-degree glideslope to a specially prepared runway on the east side of Rogers Dry Lake, with the landing gear remaining retracted.

Passing the decision height of 150 feet above ground level (AGL), the airplane turned slightly to the right of the desired path, entering into a situation known as a Dutch roll. Slightly above that decision point at which the  pilot was to execute a “go-around” maneuver. There appeared to be enough altitude to maneuver back to the center-line of the runway. The aircraft was below the glideslope and below the desired airspeed. At this point, the data acquisition systems had been activated, and the plane was committed to impact. That situation had to have almost a strange feeling to it…that point of knowing that the plane was going to crash and knowing that the crash was exactly what you wanted it to do. Then the plane contacted the ground, left wing low, at full throttle, with its nose pointing to the left of the center-line. The original plan was that “the aircraft would land wings-level, with the throttles set to idle, and exactly on the center-line during the CID, thus allowing the fuselage to remain intact as the wings were sliced open by eight posts cemented into the runway (called “Rhinos” due to the shape of the “horns” welded onto the posts).” The Boeing 720 had a surprise in store for the researchers, when it landed askew. “One of the Rhinos sliced through the number 3 engine, behind the burner can, leaving the engine on the wing pylon, which does not typically happen in an impact of this type. The same rhino then sliced through the fuselage, causing a cabin fire when burning fuel was able to enter the fuselage.”

pilot was to execute a “go-around” maneuver. There appeared to be enough altitude to maneuver back to the center-line of the runway. The aircraft was below the glideslope and below the desired airspeed. At this point, the data acquisition systems had been activated, and the plane was committed to impact. That situation had to have almost a strange feeling to it…that point of knowing that the plane was going to crash and knowing that the crash was exactly what you wanted it to do. Then the plane contacted the ground, left wing low, at full throttle, with its nose pointing to the left of the center-line. The original plan was that “the aircraft would land wings-level, with the throttles set to idle, and exactly on the center-line during the CID, thus allowing the fuselage to remain intact as the wings were sliced open by eight posts cemented into the runway (called “Rhinos” due to the shape of the “horns” welded onto the posts).” The Boeing 720 had a surprise in store for the researchers, when it landed askew. “One of the Rhinos sliced through the number 3 engine, behind the burner can, leaving the engine on the wing pylon, which does not typically happen in an impact of this type. The same rhino then sliced through the fuselage, causing a cabin fire when burning fuel was able to enter the fuselage.”

“The cutting of the number 3 engine and the full-throttle situation was significant, as this was outside the test envelope. The number 3 engine continued to operate for approximately 1/3 of a rotation, degrading the fuel and igniting it after impact, providing a significant heat source. The fire and smoke took over an hour to extinguish. The CID impact was spectacular with a large fireball created by the number 3 engine on the right side, enveloping and burning the aircraft. From the standpoint of AMK the test was a major set-back. For NASA Langley, the data collected on crashworthiness was deemed successful and just as important.”

The actual impact proved that the antimisting additive they had tested was not going to prevent a post-crash fire in all situations, but the reduced intensity of the initial fire was attributed to the effect of the AMK. FAA investigators estimated that 23% to 25% of the aircraft’s full capacity of 113 people could have survived the crash. Now that is saying something, considering the way the crash looked to observers. “Time from slide-out to complete smoke obscuration for the forward cabin was 5 seconds; for the aft cabin, it was 20 seconds. Total time to evacuate was 15 and 33 seconds respectively, accounting for the time necessary to reach and open the doors and operate the slide.” The FAA instituted new flammability standards for seat cushions which required the use of fire-blocking layers as a result of analysis of the crash, resulting in seats which performed better than those in the test. From this crash demonstration, came the implementation of a standard requiring floor  proximity lighting to be mechanically fastened, due to the apparent detachment of two types of adhesive-fastened emergency lights during the impact. In addition, federal aviation regulations for flight data recorder sampling rates for pitch, roll, and acceleration were found to be insufficient. NASA determined that at the point of impact, the piloting task workload unusually high, which might have been reduced through the use of a heads-up display, the automation of more tasks, and a higher-resolution monitor. The use of a microwave landing system to improve tracking accuracy over the standard instrument landing system was also recommended. The Global Positioning System-based Wide Area Augmentation System came to fulfill this role.

proximity lighting to be mechanically fastened, due to the apparent detachment of two types of adhesive-fastened emergency lights during the impact. In addition, federal aviation regulations for flight data recorder sampling rates for pitch, roll, and acceleration were found to be insufficient. NASA determined that at the point of impact, the piloting task workload unusually high, which might have been reduced through the use of a heads-up display, the automation of more tasks, and a higher-resolution monitor. The use of a microwave landing system to improve tracking accuracy over the standard instrument landing system was also recommended. The Global Positioning System-based Wide Area Augmentation System came to fulfill this role.