When corporate mining projects expanded and began to need a number of workers, the next logical step is to provide housing for the miners. By building a “company town” they could also control the rent, often making it necessary for the miners to spend all their wages, and even go into debt to get the things they needed to live. The “company town” of Gilman, Colorado was founded in 1886 during the Colorado Silver Boom, the town later became a center of lead and zinc mining in Colorado. The town was centered on the now-flooded Eagle Mine. When toxic pollutants, including contamination of the ground water in 1984, the town was abandoned by order of the Environmental Protection Agency. It was also due to unprofitability of the mines, meaning there was no longer a need for a “company town.”

When corporate mining projects expanded and began to need a number of workers, the next logical step is to provide housing for the miners. By building a “company town” they could also control the rent, often making it necessary for the miners to spend all their wages, and even go into debt to get the things they needed to live. The “company town” of Gilman, Colorado was founded in 1886 during the Colorado Silver Boom, the town later became a center of lead and zinc mining in Colorado. The town was centered on the now-flooded Eagle Mine. When toxic pollutants, including contamination of the ground water in 1984, the town was abandoned by order of the Environmental Protection Agency. It was also due to unprofitability of the mines, meaning there was no longer a need for a “company town.”

The town sat empty until 2007, when The Ginn Company began to make plans to build a private ski resort with private home sites across Battle Mountain, which would include development at the Gilman townsite. The Minturn Town Council, which held jurisdiction over Gilman, unanimously approved annexation and development  plans for 4,300 acres (6.7 square miles) of Ginn Resorts’ 1,700-unit Battle Mountain residential ski and golf resort, on February 27, 2008. Ginn’s Battle Mountain development would also include much of the old Gilman townsite. I’m not sure how I feel about that. To restore an old structure for a similar use is one thing, but to make it a ski resort seems wrong somehow. Then again, I guess as housing, it probably wouldn’t have been in the proper location to use as housing. On May 20, 2008, the town of Minturn approved the annexation in a public referendum with 87% of the vote. Then, as of September 9, 2009, the Ginn Company backed out of development plans for the Battle Mountain Property, so once again the site will be left to decay. Crave Real Estate Ventures, who was the original finance to Ginn, took over day to day operations of the property. For now, and the foreseeable future, Gilman is a ghost town on private property and is strictly off limits to the public.

plans for 4,300 acres (6.7 square miles) of Ginn Resorts’ 1,700-unit Battle Mountain residential ski and golf resort, on February 27, 2008. Ginn’s Battle Mountain development would also include much of the old Gilman townsite. I’m not sure how I feel about that. To restore an old structure for a similar use is one thing, but to make it a ski resort seems wrong somehow. Then again, I guess as housing, it probably wouldn’t have been in the proper location to use as housing. On May 20, 2008, the town of Minturn approved the annexation in a public referendum with 87% of the vote. Then, as of September 9, 2009, the Ginn Company backed out of development plans for the Battle Mountain Property, so once again the site will be left to decay. Crave Real Estate Ventures, who was the original finance to Ginn, took over day to day operations of the property. For now, and the foreseeable future, Gilman is a ghost town on private property and is strictly off limits to the public.

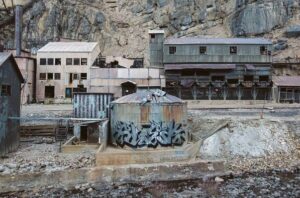

While it is illegal to go into the town, aerial views of it can still give an idea of what the town looked like. It makes me rather sad that people can’t go in and explore the old “company town” anymore, but I suppose they would need to decide it’s future before allowing the public to have access. Unfortunately, the public came be a  destructive force when it is turned loose on ruins. Right now, the townsite is a victim of vandalism, and the town’s main street is heavily tagged with graffiti. There are only a few intact windows left in town, as twenty years of vandalism have left almost every glass object in the town destroyed. Still, there are many parts of the town are almost as they were when the mine shut down. The main shaft elevators still sit ready for ore cars, permanently locked at the top level. Several cars and trucks still sit in their garages, left behind by their owners. Because of its size, modernity and level of preservation, the town is also the subject of interest for many historians, explorers, and photographers. I guess, “off limits to the public” doesn’t mean much.

destructive force when it is turned loose on ruins. Right now, the townsite is a victim of vandalism, and the town’s main street is heavily tagged with graffiti. There are only a few intact windows left in town, as twenty years of vandalism have left almost every glass object in the town destroyed. Still, there are many parts of the town are almost as they were when the mine shut down. The main shaft elevators still sit ready for ore cars, permanently locked at the top level. Several cars and trucks still sit in their garages, left behind by their owners. Because of its size, modernity and level of preservation, the town is also the subject of interest for many historians, explorers, and photographers. I guess, “off limits to the public” doesn’t mean much.

Leave a Reply