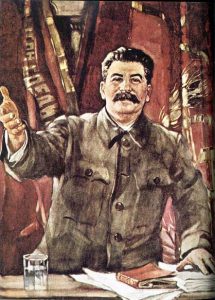

I suppose that turning on any government could be viewed at treason, but some governments are so evil and so corrupt that the citizens have no choice but to take them down, and as in the case of the Soviet regime, even the members of the government themselves could be viewed as treasonous and subject to removal. The big difference with the Soviet regime was that when the government officials were being removed, they were also being killed. The event was called The Great Purge, and as the name implies, the idea was to remove, in this case permanently, anyone who disagreed with Stalin and his way of running the regime. It was also called The Great Terror and Ezhovshchina (after the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs, Nikolai Ezhov, who oversaw the process before he himself became one of its casualties). No one was safe from the long arm of Stalin.

I suppose that turning on any government could be viewed at treason, but some governments are so evil and so corrupt that the citizens have no choice but to take them down, and as in the case of the Soviet regime, even the members of the government themselves could be viewed as treasonous and subject to removal. The big difference with the Soviet regime was that when the government officials were being removed, they were also being killed. The event was called The Great Purge, and as the name implies, the idea was to remove, in this case permanently, anyone who disagreed with Stalin and his way of running the regime. It was also called The Great Terror and Ezhovshchina (after the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs, Nikolai Ezhov, who oversaw the process before he himself became one of its casualties). No one was safe from the long arm of Stalin.

The Great Purge, the state-organized bloodshed…slaughter really, that overwhelmed the Communist Party and Soviet society took place from 1936 to 1938. The real reasons for these heinous attacks on government officials within the Soviet regime remain largely unknown, but it’s easy to imagine that Stalin irrationally felt like his men were trying to take over the operation, or run from it, and so they had to be removed. Of course, they said it was in response to terror attacks or threatened terror attacks, but to think anyone believed that is more insane than the act itself.

Of course, Stalin had to do things “right,” so he held three elaborately staged show trials of former high-ranking Communists. In July-August 1936, in the first show trial, Lev Kamenev, Grigorii Zinoviev, and fourteen others were convicted of having organized a Trotskyite-Zinovievite terrorist center that allegedly had been formed in 1932. In the end, they were found guilty of the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934. This first trial did little to satisfy Stalin, not did the efforts of the police to investigate and liquidate such “nefarious plots.” So, Stalin replaced Genrikh Iagoda with Nikolai Ezhov as head of the NKVD in September 1936. In January 1937, a second show trial was held, with Iurii Piatakov and other leading figures in the industrialization drive as the chief defendants. At a mandatory session of the party’s Central Committee in February-March 1937, Nikolai Bukharin and Aleksei Rykov, who were the most prominent party members associated with the so-called Rightist deviation of the late 1920s and early 1930s, were accused of having collaborated with the Trotskyite-Zinovievite terrorists as well as with foreign intelligence agencies. In March 1938, in the third show trial, they along with Iagoda and others were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death.

The period of time between the second and third show trials saw the upper echelon of the Red Army, provincial party secretaries, party and state personnel among the national minorities, industrial managers, and other officials destroyed by arrests and summary executions. As the “process” of torture, threats, and executions continued, it fed upon itself. The accused under severe physical and psychological pressure from their interrogators, named names and confessed to outlandish crimes…all probably fake and forced. Millions of others, terrified of being accused themselves, became involved in the frenzied search for “enemies of the people.” On July 3, 1937, the Politbiuro ordered Ezhov to conduct “mass operations” to locate and arrest recidivist criminals, ex-kulaks, and other “anti-Soviet elements,” all of whom were prosecuted by three-person  tribunals. Ezhov actually established quotas in each district for the number of arrests, meaning that more arrests were made for trumped-up charges. Ezhov’s projected totals of 177,500 exiled and 72,950 executed were eventually exceeded in what was an absolute witch hunt.

tribunals. Ezhov actually established quotas in each district for the number of arrests, meaning that more arrests were made for trumped-up charges. Ezhov’s projected totals of 177,500 exiled and 72,950 executed were eventually exceeded in what was an absolute witch hunt.

The repercussions of this horrific time in history are unknown. The situation, that began as a bloody retribution against what was already a defeated political opposition, soon developed into a its own class of disease within the political body. Its psychological consequences among the survivors were long-lasting and incalculable…mostly fear of dying and fear of anyone in authority.

Leave a Reply