Monthly Archives: December 2022

Every time I hear about a lost treasure, I wonder how many such treasures there are around the world. Some of these treasures are most likely lost forever, and one of those (so far anyway) is “The Old Spanish Treasure” which isn’t a treasure in a tropical, mysterious location from a long-ago shipwreck. Legend has it that the treasure is located in “The Old Spanish Treasure Cave,” which is actually located along the Missouri-Arkansas border. The location in and of itself, makes me wonder why no one has ever recovered the treasure.

Every time I hear about a lost treasure, I wonder how many such treasures there are around the world. Some of these treasures are most likely lost forever, and one of those (so far anyway) is “The Old Spanish Treasure” which isn’t a treasure in a tropical, mysterious location from a long-ago shipwreck. Legend has it that the treasure is located in “The Old Spanish Treasure Cave,” which is actually located along the Missouri-Arkansas border. The location in and of itself, makes me wonder why no one has ever recovered the treasure.

Apparently, about 400 years ago, Spanish conquistadors headed north in the dead of winter, raiding Native American villages as they went. During the raids, they accumulated a great amount of treasure, but the winter was raging, and they needed a place to get out of the cold. So, the conquistadors took refuge in a large cave. Of  course, they thought they were alone, but that couldn’t have been further from the truth. The Native Americans saw their campfire smoke coming out of a natural chimney at the top of the cave. Taking their revenge, the Native Americans attacked the conquistadors, leaving only one survivor.

course, they thought they were alone, but that couldn’t have been further from the truth. The Native Americans saw their campfire smoke coming out of a natural chimney at the top of the cave. Taking their revenge, the Native Americans attacked the conquistadors, leaving only one survivor.

Somehow keeping his wits about him, the survivor sealed all but one entrance and drew two maps…one on parchment, and one etched into a limestone rock. While the rock bearing the map was recovered, the treasure has yet to be found. The location of the cave is known, and I’m sure it and the map have been scoured repeatedly, but the survivor hid his treasure well. It almost makes me wonder if he hid it at all. Maybe he just took it with him or went back for it soon after it was hidden, and then simply left the map to throw people off the trail.

The cave was sealed up until it was re-discovered in 1885 by an old Spaniard from Madrid. As the story goes, old Spaniard the legend apparently led him to two maps…one on a tree, and another on a rock. Neither these maps nor the treasure, estimated today at 40 million dollars, have ever been found, but there have been a number of artifacts found, like helmets, pieces of armor, and weapons from the period. Some have even claimed to have found a few gold coins, but there is no proof of that. The Spaniard was ill, and so did not stay long. Other people continued to search for the treasure for many years, but to no avail. To this day, the elusive treasure remains hidden, and I suppose it always will.

The cave was sealed up until it was re-discovered in 1885 by an old Spaniard from Madrid. As the story goes, old Spaniard the legend apparently led him to two maps…one on a tree, and another on a rock. Neither these maps nor the treasure, estimated today at 40 million dollars, have ever been found, but there have been a number of artifacts found, like helmets, pieces of armor, and weapons from the period. Some have even claimed to have found a few gold coins, but there is no proof of that. The Spaniard was ill, and so did not stay long. Other people continued to search for the treasure for many years, but to no avail. To this day, the elusive treasure remains hidden, and I suppose it always will.

“Terrible Tilly” came by her name honesty, because from the start, the lighthouse seemed to be nothing but trouble. “Terrible Tilly” is the nickname of the Tillamook Lighthouse sits on top of a sea stack of basalt, more than a mile off the banks of Oregon’s North Coast. Looking to put up a lighthouse in the area Tilly’s story began in 1878 when a solid basalt rock was selected as the location for a lighthouse off the coast of Tillamook Head. Any construction work can have its dangers, but construction a mile offshore in all kinds of weather, can be particularly dangerous. Such was the case with “Terrible Tilly” when even before the work began, a master mason surveying the location was swept out to sea, never to be seen again.

“Terrible Tilly” came by her name honesty, because from the start, the lighthouse seemed to be nothing but trouble. “Terrible Tilly” is the nickname of the Tillamook Lighthouse sits on top of a sea stack of basalt, more than a mile off the banks of Oregon’s North Coast. Looking to put up a lighthouse in the area Tilly’s story began in 1878 when a solid basalt rock was selected as the location for a lighthouse off the coast of Tillamook Head. Any construction work can have its dangers, but construction a mile offshore in all kinds of weather, can be particularly dangerous. Such was the case with “Terrible Tilly” when even before the work began, a master mason surveying the location was swept out to sea, never to be seen again.

Even with the dangers and the loss, work began in 1880, and the lighthouse went into operation in 1881. In those days…the days before GPS, lighthouses were a vital part of the shipping business. The ships couldn’t see the  dangers that lurked in the night, so knowing what was just below the surface, or even above the surface of the water was very important. As ships got closer to shore, the possibility of hitting rock or small island could be disastrous. Never was that more evident that the disaster that occurred just a few weeks before the lighthouse opened. A ship sailed too close to the shore because of low visibility, and crashed, killing all 16 crew members. The need for the lighthouse was proven once again, in a very sad way.

dangers that lurked in the night, so knowing what was just below the surface, or even above the surface of the water was very important. As ships got closer to shore, the possibility of hitting rock or small island could be disastrous. Never was that more evident that the disaster that occurred just a few weeks before the lighthouse opened. A ship sailed too close to the shore because of low visibility, and crashed, killing all 16 crew members. The need for the lighthouse was proven once again, in a very sad way.

While you might think that making the lighthouse operation would have ended the tragic connections with “Terrible Tilly,” but that really wasn’t the case. The conditions on the lighthouse were extremely rough, and one lighthouse keeper even allegedly went insane. Being even just a mile offshore, made life very isolated. The storms beat on the lighthouse, and I’m sure they sometimes wondered if the lighthouse could take it. The howling wind can be enough to drive some people crazy. Living in Wyoming, I know that there are times when  we wonder if the wind will ever quit. When it finally does, it is almost shockingly quiet. Not everyone can take the howling wind.

we wonder if the wind will ever quit. When it finally does, it is almost shockingly quiet. Not everyone can take the howling wind.

As GPS came into being, the need for lighthouses is becoming less and less. It’s rather a sad fact, because these icons of history, are fading into the past, and for me, that feels very sad. Decades after the lighthouse was decommissioned in 1957, it was turned into a columbarium, which is a storehouse for urns of cremated remains. To this day, the remains of 30 people are still stored inside the lighthouse. “Terrible Tilly” was closed down in 1957 and remains off limits to the public to this day.

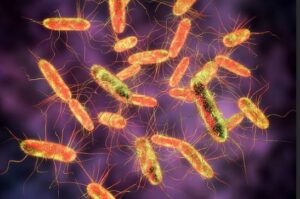

No disease, especially those that are highly contagious, and for which there is no known cure, is easy to find out that one has, and for those who might have been around the victim of said disease, it can be very frightening. Mary Mallon, who was born September 23, 1869, Cookstown, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, immigrated to the United States in 1883. Possessing minimal skills, she made her living as a domestic servant, most often as a cook. At some point, she became a carrier of the typhoid bacterium (Salmonella typhi), although no one really knows exactly when or how that happened. Nevertheless, between 1900 and 1907, nearly two dozen people fell ill with typhoid fever in households in New York City and Long Island where Mallon worked. That was the first clue that she was a carrier, because the illnesses often occurred shortly after she began working in each household, then by the time the disease was traced to its source in a household where she had recently been employed, Mallon had already moved on, with no forwarding address. The whole dilemma made it very hard to really track down the carrier, and she knew nothing about it, because she wasn’t ill. It is unusual to be asymptomatic, but not impossible, and Typhoid Mary was one of the unusual ones.

No disease, especially those that are highly contagious, and for which there is no known cure, is easy to find out that one has, and for those who might have been around the victim of said disease, it can be very frightening. Mary Mallon, who was born September 23, 1869, Cookstown, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, immigrated to the United States in 1883. Possessing minimal skills, she made her living as a domestic servant, most often as a cook. At some point, she became a carrier of the typhoid bacterium (Salmonella typhi), although no one really knows exactly when or how that happened. Nevertheless, between 1900 and 1907, nearly two dozen people fell ill with typhoid fever in households in New York City and Long Island where Mallon worked. That was the first clue that she was a carrier, because the illnesses often occurred shortly after she began working in each household, then by the time the disease was traced to its source in a household where she had recently been employed, Mallon had already moved on, with no forwarding address. The whole dilemma made it very hard to really track down the carrier, and she knew nothing about it, because she wasn’t ill. It is unusual to be asymptomatic, but not impossible, and Typhoid Mary was one of the unusual ones.

Finally, in 1906, after 6 people in a household of 11 where Mallon had worked in Oyster Bay, New York, became sick with typhoid, the home’s owners hired New York City Department of Health sanitary engineer George Soper to investigate the outbreak. Soper’s specialty was studying typhoid fever epidemics, so he was just the man for the job. Of course, Soper was not the only investigator looking for the carrier of the dreaded typhoid disease. Typhoid can usually be cured these days using medications like Ciprofloxacin and Ceftriaxone, but in those days, it meant a death sentence for many people. As the investigation continued, it was concluded that the outbreak had likely been caused by contaminated water. Mallon continued to work as a cook, moving from household to household until 1907. Finally in the right place at the right time, Mallon was located working in a Park Avenue home in Manhattan. The winter of that year, following an outbreak in the Manhattan household that involved a death from the disease, Soper met with Mallon. Following extensive tests, he linked all 22 cases of typhoid fever that had been recorded in New York City and the Long Island area to her. It was this connection that earner her the “unwanted” nickname of Typhoid Mary.

A scared Mallon fled the area, but authorities led by Soper finally overtook her and had her committed to an isolation center on North Brother Island, which is a part of the Bronx, New York. There she stayed, despite an appeal to the US Supreme Court. She was finally released in 1910, when the health department released her on condition that she never again accept employment that involved the handling of food. These days she might have been able to go back to work as a cook, but at that time they couldn’t successfully test for the presence of the bacteria in a person, and with the very real possibility of passing the contagion through food, it was a risk they couldn’t take.

Unfortunately for Mallon, an epidemic four years later, brought her once again into the spotlight. The epidemic

was at a sanatorium in Newfoundland, New Jersey, and at Sloane Maternity Hospital in Manhattan. Mallon had worked as a cook at both places. Mallon was at last found in a suburban home in Westchester County, New York, and was returned to North Brother Island, where she remained for the rest of her life. In 1932, she suffered a paralytic stroke that led to her slow death six years later.

was at a sanatorium in Newfoundland, New Jersey, and at Sloane Maternity Hospital in Manhattan. Mallon had worked as a cook at both places. Mallon was at last found in a suburban home in Westchester County, New York, and was returned to North Brother Island, where she remained for the rest of her life. In 1932, she suffered a paralytic stroke that led to her slow death six years later.

Mallon claimed to have been born in the United States, but it was later determined that she was an immigrant. Although she herself was immune to the typhoid bacillus, 51 original cases of typhoid and three deaths were directly attributed to Typhoid Mary. There were also countless more that were indirectly attributed to her as people she infected, passed the illness to people they came in contact with.

I suppose that turning on any government could be viewed at treason, but some governments are so evil and so corrupt that the citizens have no choice but to take them down, and as in the case of the Soviet regime, even the members of the government themselves could be viewed as treasonous and subject to removal. The big difference with the Soviet regime was that when the government officials were being removed, they were also being killed. The event was called The Great Purge, and as the name implies, the idea was to remove, in this case permanently, anyone who disagreed with Stalin and his way of running the regime. It was also called The Great Terror and Ezhovshchina (after the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs, Nikolai Ezhov, who oversaw the process before he himself became one of its casualties). No one was safe from the long arm of Stalin.

I suppose that turning on any government could be viewed at treason, but some governments are so evil and so corrupt that the citizens have no choice but to take them down, and as in the case of the Soviet regime, even the members of the government themselves could be viewed as treasonous and subject to removal. The big difference with the Soviet regime was that when the government officials were being removed, they were also being killed. The event was called The Great Purge, and as the name implies, the idea was to remove, in this case permanently, anyone who disagreed with Stalin and his way of running the regime. It was also called The Great Terror and Ezhovshchina (after the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs, Nikolai Ezhov, who oversaw the process before he himself became one of its casualties). No one was safe from the long arm of Stalin.

The Great Purge, the state-organized bloodshed…slaughter really, that overwhelmed the Communist Party and Soviet society took place from 1936 to 1938. The real reasons for these heinous attacks on government officials within the Soviet regime remain largely unknown, but it’s easy to imagine that Stalin irrationally felt like his men were trying to take over the operation, or run from it, and so they had to be removed. Of course, they said it was in response to terror attacks or threatened terror attacks, but to think anyone believed that is more insane than the act itself.

Of course, Stalin had to do things “right,” so he held three elaborately staged show trials of former high-ranking Communists. In July-August 1936, in the first show trial, Lev Kamenev, Grigorii Zinoviev, and fourteen others were convicted of having organized a Trotskyite-Zinovievite terrorist center that allegedly had been formed in 1932. In the end, they were found guilty of the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934. This first trial did little to satisfy Stalin, not did the efforts of the police to investigate and liquidate such “nefarious plots.” So, Stalin replaced Genrikh Iagoda with Nikolai Ezhov as head of the NKVD in September 1936. In January 1937, a second show trial was held, with Iurii Piatakov and other leading figures in the industrialization drive as the chief defendants. At a mandatory session of the party’s Central Committee in February-March 1937, Nikolai Bukharin and Aleksei Rykov, who were the most prominent party members associated with the so-called Rightist deviation of the late 1920s and early 1930s, were accused of having collaborated with the Trotskyite-Zinovievite terrorists as well as with foreign intelligence agencies. In March 1938, in the third show trial, they along with Iagoda and others were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death.

The period of time between the second and third show trials saw the upper echelon of the Red Army, provincial party secretaries, party and state personnel among the national minorities, industrial managers, and other officials destroyed by arrests and summary executions. As the “process” of torture, threats, and executions continued, it fed upon itself. The accused under severe physical and psychological pressure from their interrogators, named names and confessed to outlandish crimes…all probably fake and forced. Millions of others, terrified of being accused themselves, became involved in the frenzied search for “enemies of the people.” On July 3, 1937, the Politbiuro ordered Ezhov to conduct “mass operations” to locate and arrest recidivist criminals, ex-kulaks, and other “anti-Soviet elements,” all of whom were prosecuted by three-person  tribunals. Ezhov actually established quotas in each district for the number of arrests, meaning that more arrests were made for trumped-up charges. Ezhov’s projected totals of 177,500 exiled and 72,950 executed were eventually exceeded in what was an absolute witch hunt.

tribunals. Ezhov actually established quotas in each district for the number of arrests, meaning that more arrests were made for trumped-up charges. Ezhov’s projected totals of 177,500 exiled and 72,950 executed were eventually exceeded in what was an absolute witch hunt.

The repercussions of this horrific time in history are unknown. The situation, that began as a bloody retribution against what was already a defeated political opposition, soon developed into a its own class of disease within the political body. Its psychological consequences among the survivors were long-lasting and incalculable…mostly fear of dying and fear of anyone in authority.