It seems odd that the daughter of a poet would be an excellent mathematician, but each person has their own gift, and it may or may not be anything like our parents. Being the daughter of a poet, in this case, Lord Byron (George Gordon Byron), it may have seemed unlikely for Ada Byron to be a mathematician, but her mother was Lady Byron (Anne Isabella Milbanke)…a mathematician. So, there you have it…two women in the 1800s who were good at mathematics. To top it off, it was uncommon for women to go very high in education in those days, much less for the aristocrat set. Women were usually trained for things like running a household and raising children…and maybe the occasional schoolteacher.

It seems odd that the daughter of a poet would be an excellent mathematician, but each person has their own gift, and it may or may not be anything like our parents. Being the daughter of a poet, in this case, Lord Byron (George Gordon Byron), it may have seemed unlikely for Ada Byron to be a mathematician, but her mother was Lady Byron (Anne Isabella Milbanke)…a mathematician. So, there you have it…two women in the 1800s who were good at mathematics. To top it off, it was uncommon for women to go very high in education in those days, much less for the aristocrat set. Women were usually trained for things like running a household and raising children…and maybe the occasional schoolteacher.

Ada Byron was the only child of Lord and Lady Byron. He had other children, but they were born out of wedlock to other women. The truth is that Ada’s mathematical prowess wasn’t an accident…it was a calculated plan by her mother, and one to which Adad didn’t object. A month after Ada was born, her parents separated, and Byron left England forever, and caused Ada’s mother to be very bitter. He wrote a poem, commemorating the parting, four months later. The poem begins, “Is thy face like thy mother’s my fair child! ADA! sole daughter of my house and heart?” When Ada was eight years old, her father died in Greece. Ada’s mother, who had never forgiven Lord Byron for leaving, remained bitter against him, even in death. In retaliation for his unfaithfulness, she promoted Ada’s interest in mathematics and logic in an effort to prevent her from developing her father’s perceived “insanity.” Nevertheless, Ada’s mother could not curb her daughter’s curiosity about her father. She remained interested in him for the rest of her life, but probably had to keep her curiosity to herself. When Ada had children of her own, she named one of her sons Byron, after her father. She also made it clear that when she died, she was to be buried next to her father, and upon her death, her request was honored.

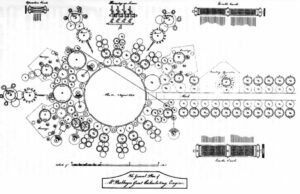

Ada’s childhood was a hard one, because she was often ill. Still, Ada pursued her studies with great care, and  she persevered even in times of illness. I think that like her mother, she preferred logic and mathematics to poetry all along. At the age of 17 Ada was introduced to Mary Somerville, a remarkable woman who translated Pierre-Simon LaPlace’s works into English, and whose texts were used at Cambridge. Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. Though Somerville encouraged Ada in her mathematical studies, she also attempted to put mathematics and technology into an appropriate human context. It was at a dinner party at Somerville’s home that Ada heard in November 1834, about Babbage’s ideas for a new calculating engine, the Analytical Engine. His thought was, “what if a calculating engine could not only foresee but could act on that foresight?” Ada was impressed by the “universality of his ideas.” She was pretty much alone in her interest.

she persevered even in times of illness. I think that like her mother, she preferred logic and mathematics to poetry all along. At the age of 17 Ada was introduced to Mary Somerville, a remarkable woman who translated Pierre-Simon LaPlace’s works into English, and whose texts were used at Cambridge. Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. Though Somerville encouraged Ada in her mathematical studies, she also attempted to put mathematics and technology into an appropriate human context. It was at a dinner party at Somerville’s home that Ada heard in November 1834, about Babbage’s ideas for a new calculating engine, the Analytical Engine. His thought was, “what if a calculating engine could not only foresee but could act on that foresight?” Ada was impressed by the “universality of his ideas.” She was pretty much alone in her interest.

In 1835, she married William King, who was made Earl of Lovelace in 1838. With that, Ada became Countess of Lovelace. Many would think that would have been the end of her mathematical career, but Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace was first an English mathematician and writer. Babbage worked on plans for this new engine and reported on the developments at a seminar in Turin, Italy in the autumn of 1841. An Italian, named Menabrea, wrote a summary of what Babbage described and published an article in French about the development. By 1843, Ada, now the married mother of three children (Byron, Anne, and Ralph) under the age of eight, translated Menabrea’s article. When she showed Babbage her translation, he suggested that she should add her own notes to the translation, which turned out to be three times the length of the original article. Letters filled with fact and fantasy flew back and forth between Babbage and Ada. In her article, published in 1843, Lady Lovelace’s prescient comments included her predictions that such a machine might be used to compose complex music, to produce graphics, and would be used for both practical and scientific use.  While the world thought that just wishful thinking, Ada was correct. In fact, she published the first algorithm intended to be carried out by such a machine. When inspired Ada could be very focused and a mathematical taskmaster. She suggested to Babbage writing a plan for how the engine might calculate Bernoulli numbers. This plan is now seen as the first “computer program” and as a result, she is often regarded as the first computer programmer. A software language developed by the US Department of Defense was named “Ada” in her honor in 1979. Ada Lovelace, died on November 27, 1852, after battling with Uterine Cancer. Like her father, she died young, at the same age he had…36 years old. Ada was abandoned by her husband because of cancer shortly before her death…what a creep he was!!

While the world thought that just wishful thinking, Ada was correct. In fact, she published the first algorithm intended to be carried out by such a machine. When inspired Ada could be very focused and a mathematical taskmaster. She suggested to Babbage writing a plan for how the engine might calculate Bernoulli numbers. This plan is now seen as the first “computer program” and as a result, she is often regarded as the first computer programmer. A software language developed by the US Department of Defense was named “Ada” in her honor in 1979. Ada Lovelace, died on November 27, 1852, after battling with Uterine Cancer. Like her father, she died young, at the same age he had…36 years old. Ada was abandoned by her husband because of cancer shortly before her death…what a creep he was!!

One Response to The First Computer Programmer