During World War II, the Allies used a number of spies, many of them women, but none of them could compare to Virginia Hall, who was considered by the Nazis to be the “most dangerous of all Allied spies.” I can’t think of a greater honor for a spy. It seems to me that the women spies were really the best spies of the war. Maybe it was because they just didn’t expect the women to be spies. That was a big advantage. Virginia Hall had one other thing that made it seem impossible to think of her as a spy…a prosthetic leg, which created a bit of a limp. It was the leg that earned Hall her other name…Limping Lady.

During World War II, the Allies used a number of spies, many of them women, but none of them could compare to Virginia Hall, who was considered by the Nazis to be the “most dangerous of all Allied spies.” I can’t think of a greater honor for a spy. It seems to me that the women spies were really the best spies of the war. Maybe it was because they just didn’t expect the women to be spies. That was a big advantage. Virginia Hall had one other thing that made it seem impossible to think of her as a spy…a prosthetic leg, which created a bit of a limp. It was the leg that earned Hall her other name…Limping Lady.

Born to wealthy parents in Baltimore, Maryland in 1906, Hall was expected to marry well, and become a wife and mother, but she had other plans. Describing herself as “cantankerous and capricious, Hall set her sights on being a diplomat after studying in Paris and falling in love with France, but out of 1500 US diplomats, only 6 were women, and Hall was turned down several times. Still hoping, she took a job as a clerical worker and the US Embassy in Warsaw, Poland. Then tragically, a hunting accident on a trip to Turkey, followed by gangrene infecting the leg, caused it to require amputation, which also disqualified her from the US Foreign Service. It was a crushing blow. She decided to resign from her job and move to Paris in 1939, just as World War II was erupting.

Hall’s life took a dramatic turn on May 10, 1940, when Germany invaded France. Volunteering to drive ambulances for the French army during the six-week long Battle of France, Hall transported wounded soldiers from the front line, while dodging fire from German fighter planes overhead. With the French surrender, Hall traveled to London to support the British war effort there. As she traveled, she impressed an undercover agent who put her in touch with a senior officer in the Special Operations Executive (SOE), which was Winston Churchill’s new secret service. Female operatives were not employed By the SOE, but after six months of failing to infiltrate a single new agent into France, they decided to send Hall to France as the SOE’s first female agent in the country. In the end, she would spend nearly the entire war in France, first as a spy for Britain’s SOE and later for the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Special Operations Branch.

Hall had a bit of a sense of humor, especially when it came to her heavy wooden leg, even nicknaming it Cuthbert. The leg was no obstacle to Hall’s courage either, nor her determination to defeat the Nazis, whom she bitterly hated. Hall used everything at her disposal while undercover in France, and proved herself “exceptionally adept at eluding the Gestapo as she organized resistance groups, masterminded jailbreaks for captured agents, mapped drop zones, reported on German troop movements, set up safe houses, and rescued escaped POWs and downed Allied pilots.” Like many veterans of that era, Even years after the war, Hall rarely talked about her extraordinary career. She attributes the habit to her years as a spy. She once said, “Many of my friends were killed for talking too much.”

Spy networks were amazingly able to hide in plane site, and when Hall arrived in the Vichy region of France in August 1941, it was under the cover story of being a war correspondent for the New York Post newspaper. Following her arrival in Toulouse, Hall established a resistance network called HECKLER, which gathered information about German troop movements and helped downed British pilots escape to safety. Following her work in Toulouse, she traveled to Lyon, where she helped coordinate activities of the French Resistance. Her plans changed when the United States entered the war. As a US citizen, she could be considered a traitor for working for the British spy networks, because the United States had been considered neutral. Hall was forced underground, but continued operating in France for another 14 months. A good spy needs to have a variety of disguises at the disposal, and Hall became adept at changing her appearance on a moment’s notice. She was also known by multiple aliases. She needed to be almost invisible, at least to the enemy. The Germans, at least early in the war, didn’t think that a woman was capable of being a spy. What a serious miscalculation that turned out to be!!

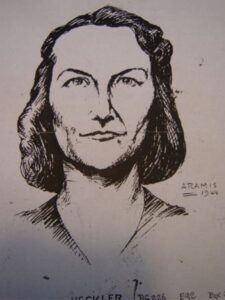

Hall’s extraordinary effectiveness amazed the SOE commanders and helped change their minds about women operating in combat zones. A year after Hall began working undercover, the SOE finally decided to send more female agents into the field. Hall’s abilities paved the way for more women to serve their countries in this important capacity. It also quickly put women spies, and Hall specifically, on the radar for the Gestapo. Soon, the hunt for “the Limping Lady” was on. They knew only her from a composite sketch, which was to her advantage. Their internal communications declared: “She is the most dangerous of all Allied spies. We must find and destroy her.” Gestapo agents…including notorious investigator Klaus Barbie, who would later be awarded the Iron Cross for torturing and executing thousands of resisters…closing in on her after the Germans seized control of Vichy France in November 1942, Hall was forced to escape to Spain.

To escape France was no easy task. It meant a three day journey on foot in heavy snow across the Pyrenees mountains. The trek was made even more challenging with an 8-pound artificial leg bound to her body with straps and a belt at the waist. At one point, she jokingly mentioned in a message to the SOE that she was concerned that “Cuthbert” would cause problems during her escape. In a funny twist, the receiver of the message didn’t recognize the nickname she used for her prosthetic. SOE headquarters responded, “If Cuthbert is giving you difficulty, have him eliminated.” In the end, it wasn’t “Cuthbert” that caused her problems. When she arrived in Spain, she was arrested and imprisoned for illegally entering the country. Hall was an inmate for six weeks before an inmate being released was able to get word to American officials in Barcelona about her presence so they could arrange her release. She finally made it back to London in January 1943, where she was quietly made a honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire.

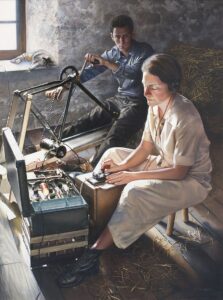

Following her imprisonment, the SOE refused to send her back to France, because they thought was too dangerous with her high profile. That decision was unacceptable to Hall, who decided to join the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which was just establishing their own intelligence operation in France. The Nazi troops were everywhere by that time, so Hall took even more extreme measures to disguise herself. Among them, a French milkmaid, causing her to need to have a rather scary dentist grind down her lovely, white American teeth. In the Haute-Loire region of central France, she disguised herself as an elderly milkmaid and got to work on her radio, coordinating airdrops of arms and supplies for the resistance fighters who were blowing up bridges and sabotaging troop trains, and reporting German troop movements to Allied forces.

Her second tour in France in 1944 and 1945 was even more successful than her first, and at its peak, her network consisted of 1,500 people. With the Germans constantly attempting to track her radio signals, Hall stayed on the move, camping out in barns and attics. As D-Day approached, Hall was operating as a guerrilla leader, and she armed and trained three battalions of French resistance fighters for sabotage missions that helped paved the way for the Allied invasion. One of her many radio reports shows the breadth of her missions. She stated that her team had destroyed four bridges, derailed freight trains, severed a key rail line, and downed telephone lines. By the war’s end, Hall had spent over three full years operating undercover behind enemy lines and, in the words of an official British government report at the end of the war, she was “amazingly successful.”

After the war, when the OSS was dissolved, it became the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Hall became an intelligence analyst. For her wartime service, she was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palme by France and became the only civilian woman during WWII to be awarded a Distinguished Service Cross by the US, which recognizes exceptional valor and risk of life in combat. President Harry Truman wanted to have a public ceremony for the presentation of the medal, but Hall requested a private ceremony instead, saying that she was “still operational and most anxious to get busy.” Hall worked at the CIA until she retired in 1966 and took

quiet pride in her service to her country, although she always maintained a wry sense of humor about it. Her response to receiving the Distinguished Service Cross was, “Not bad for a girl from Baltimore.”

quiet pride in her service to her country, although she always maintained a wry sense of humor about it. Her response to receiving the Distinguished Service Cross was, “Not bad for a girl from Baltimore.”

While in Haute-Loire, Hall had met and fallen in love with an OSS lieutenant, Paul Goillot, who worked for her. In 1957, the couple married after living together off-and-on for years. Hall went on to head the CIA. The other four heads were men. Hall was code named Marie and Diane, but the Germans gave her the nickname Artemis, and the Gestapo reportedly considered her “the most dangerous of all Allied spies.” Because of her artificial foot, she was also known as “the limping lady.” She died on July 8, 1982 at the age of 76 in Barnesville, Maryland.

Leave a Reply