As nursing goes, I suppose you could say that World War I changed everything. War is an ugly business, and wounded men (and women these days) are just a part of the unavoidable side effects of it. As the upheaval of World War I changed the world, so the horrors of it, changed nursing.

As nursing goes, I suppose you could say that World War I changed everything. War is an ugly business, and wounded men (and women these days) are just a part of the unavoidable side effects of it. As the upheaval of World War I changed the world, so the horrors of it, changed nursing.

From 1914 to 1918, what was dubbed “the war to end all wars” in the innocence of the times, anyway…led to the mobilization of more than 70 million military personnel, including 60 million Europeans, making it one of the largest wars in history. As we know, it was hardly the war to end all wars, but it did change many of the things we had come to expect war to be. World War I was one of the deadliest conflicts in history. The death toll is staggering…estimated nine million combatants and seven million civilian deaths, as a direct result of the war. To add to that total, came the resulting genocides, as well as the 1918 influenza pandemic, which caused another 50 to 100 million deaths worldwide.

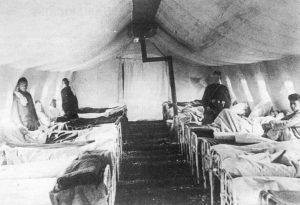

Now, just imagine being a nurse in those days. Of course, medical tents and hospitals were close to the perimeter of the fighting, to care for hurt soldiers quickly. This assured that the World War I nurses were witness to the conflict firsthand. I seriously doubt if any of them walked away from the war with less PTSD than the soldiers did. Many of them wrote about their involvement in diaries and letters that, similar to photographs from this time, offer insight into how they were personally impacted. The journals also include details about fighting, disease, and the hope that nurses and soldiers alike found in their darkest moments…if there could be any hope to be found.

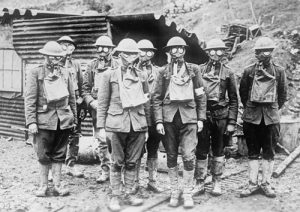

It was in World War I that Germany introduced gas as a new form of aggression in 1915. It was in many ways the latest form of terrorism. To say that it was a different level of engagement seems an understatement. Gas devices became commonplace. They were worn anytime an air raid siren sounded, and some people wore them much of the time, as a precaution. The soldiers didn’t go anywhere without their gas mask. It was their life-line. Still, they were among the most feared elements of World War I.

“Sister Edith Appleton was a British nurse who served in France during World War I. She wrote about the soldiers stricken by gas and the adverse physical impacts they endured. The minimal immediate effects are tearing of the eyes, but subsequently, it causes build-up of fluid in the lungs, known as pulmonary edema, leading to death. It is estimated that as many as 85% of the 91,000 gas deaths in WWI were a result of phosgene or the related agent, diphosgene (trichloromethane chloroformate).”

Margaret Trevenen Arnold, a volunteer British Red Cross nurse in France in 1915 kept a diary of her time at Le Tréport and described “groans, and moans, and shouts, and half-dazed mutterings, and men with trephined heads suddenly sitting bolt upright… It was awful, and I really know now what [conflict] means.” These serious head injuries would most likely cause permanent brain damage for these men…if they survived at all.

Some hospital tents were eerily quiet, because the men in them were too sick to make a sound. Bandages were changed as often as every two hours, in an effort to ward off infection, and tourniquets to stop the bleeding until the soldier could be sent to surgery. Most of these field “hospitals” faced the same serious conditions…a lack of clean water and sterile surroundings. The nurses had to make due with what they had…and that often wasn’t much. Sometimes the lack of medicine became a major issue, especially when it came to anesthesia. Sometimes, the soldier had to simply force himself to remain calm, and steel himself to the inevitable pain of the surgery. These men had to place their faith in the doctors and nurses who cared for them, and they had not had time to even prepare for the need for surgery…let alone without anesthesia.

“Violet Gosset served on the Western Front from 1915 to 1919. While working at a hospital in Boulogne, France, Gosset kept notes about her experiences. She described a lack of supplies, overcrowded conditions, and scrapes that often resulted from a lack of adequate protection.”

“Helen Dare Boylston, an American nurse who served in France with the Harvard Unit medical team, had patients that spanned a wide range of age demographics. Some of the soldiers were just teenagers (“boys”), while others were in their 20s. However, Boylston recalled at least one soldier in his 60s (she called him “Dad”). Boylston saw the number of men in her care rise significantly in March 1918. At this time, she was sent…with two other nurses…to care for 500 soldiers. Boylston and her fellow nurses, including one named Ruth, quickly adapted to their conditions.”

Trench warfare was a shock to most of the soldiers. Still, most soldiers remained in good spirits. A part of nursing that might be considered a little different in the field hospitals is that the nurses are “in charge of” morale to a great degree. whether the men had Trench Foot, were sick, or wounded, they needed to have someone to lift their spirits. Who would have ever thought of nurses as morale boosters, but it was so.

Flu was widespread during World War I, even before the pandemic of 1918. After the pandemic began, things became critical. Now, nurses had to contend with treatment and prevention, in addition to other issues. One problem is that soldiers who ended up in medical tents and hospitals were often covered in mud, and flies frequently buzzed around them. Keeping germs at bay was next to impossible.

“Nurse Helen Dare Boylston was a keen observer of how soldiers reacted when they returned from the front, especially when they interacted with female nurses. She commented on the “fascinating game” of casual

romance that commonly played out in the midst of conflict-related stress.” This was probably one of the most unusual phenomena, because nurses are told not to get emotionally involved, and yet here it was exactly what was needed. Nursing has changed over the years, but never has it been so evident as in World War I. It was as if nurses were making it up as they went along…and maybe they were.

romance that commonly played out in the midst of conflict-related stress.” This was probably one of the most unusual phenomena, because nurses are told not to get emotionally involved, and yet here it was exactly what was needed. Nursing has changed over the years, but never has it been so evident as in World War I. It was as if nurses were making it up as they went along…and maybe they were.

Leave a Reply