It was a typical day in Texas City, Texas…a port city in Galveston Bay. April was always warm, in the mid-70s, so it was perfect outdoor weather. Fires around the docks were a fairly common occurrence in Texas City, and it was not unusual for residents to travel down to the docks to watch the fires and the firemen working. Fires tend to attract the casual observer as well as the local news agencies. This day started out just as any other typical Texas day, but all that would change very soon. On the morning of April 16, 1947 a fire broke out on the S.S. Grandcamp. The fire produced a dense, brilliantly colored smoke that could be seen all over town. On board Grandcamp, among other things, was a supply of ammonium nitrate, which was producing the brilliant colors. The ship was docked in the Texas City port, so the smoke could be seen all over town. This fire, like any other, brought anybody who had any free time down to the dock to watch the action. This would be a fatal mistake for many of the bystanders.

It was a typical day in Texas City, Texas…a port city in Galveston Bay. April was always warm, in the mid-70s, so it was perfect outdoor weather. Fires around the docks were a fairly common occurrence in Texas City, and it was not unusual for residents to travel down to the docks to watch the fires and the firemen working. Fires tend to attract the casual observer as well as the local news agencies. This day started out just as any other typical Texas day, but all that would change very soon. On the morning of April 16, 1947 a fire broke out on the S.S. Grandcamp. The fire produced a dense, brilliantly colored smoke that could be seen all over town. On board Grandcamp, among other things, was a supply of ammonium nitrate, which was producing the brilliant colors. The ship was docked in the Texas City port, so the smoke could be seen all over town. This fire, like any other, brought anybody who had any free time down to the dock to watch the action. This would be a fatal mistake for many of the bystanders.

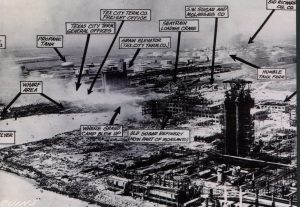

The ammonium nitrate on board the Grandcamp detonated at 9:12 am, blowing he ship apart and sending the cargo of peanuts, tobacco, twine, bunker oil and the remaining bags of ammonium nitrate 2,000 to 3,000 feet into the air. Fireballs streaked across the sky and could be seen for miles across Galveston Bay as molten ship fragments erupted out of the pier. The blast sent a fifteen foot tidal wave crashing onto the dock and flooding the surrounding area. Windows were shattered in Houston, 40 miles to the north, and people in Louisiana felt the shock 250 miles away. Most of the buildings closest to the blast were flattened, and there were many more that had doors and roofs blown off. The Monsanto plant which was only three hundred feet away, was destroyed by the blast. Most of the Texas City Terminal Railways’ warehouses along the docks were destroyed. Hundreds of employees, pedestrians and bystanders were killed. At the time of the Grandcamp’s explosion, only two additional vessels were docked in port…the S.S. High Flyer and the Wilson B. Keene, both American C-2 cargo ships similar to the Grandcamp.

The intensity of the blast sent shrapnel tearing into the surrounding area. Flaming debris ignited giant tanks full  of oil and chemicals stored at the refineries, causing a set of secondary fires and smaller explosions. The Longhorn II, a barge anchored in port, was lifted out of the water by the sheer force of the explosion and landed 100 feet away on the shore. Buildings blazed long after the initial explosion, provoking large scale emergency relief efforts throughout the day, that night, and into the following day. The fires in nearby industrial buildings and chemical plants spread the destruction even farther. The chief and 27 firefighters from the Texas City Fire Department were killed in the initial blast. Official estimates put the death toll at 567 and injuries at more than 5,000. Some of the dead were never identified, and some may never have been found at all.

of oil and chemicals stored at the refineries, causing a set of secondary fires and smaller explosions. The Longhorn II, a barge anchored in port, was lifted out of the water by the sheer force of the explosion and landed 100 feet away on the shore. Buildings blazed long after the initial explosion, provoking large scale emergency relief efforts throughout the day, that night, and into the following day. The fires in nearby industrial buildings and chemical plants spread the destruction even farther. The chief and 27 firefighters from the Texas City Fire Department were killed in the initial blast. Official estimates put the death toll at 567 and injuries at more than 5,000. Some of the dead were never identified, and some may never have been found at all.

The blast registered on a seismograph as far away as Denver, Colorado. Dockworker Pete Suderman remembers flying thirty feet as the blast carried him and several of the dock’s three-inch wooden planks across the pier. Nattie Morrow was in her home with her two children and sister-in-law Sadie. She watched the billowing smoke near the Monsanto plant from her back porch just prior to the blast. “Suddenly a thundering boom sounded, and seconds later the door ripped off its facing, skidded across the kitchen floor, and slammed down onto the table where I sat with the baby. The house toppled to one side and sat off its piers at a crazy angle. Broken glass filled the air, and we didn’t know what was happening.”

At the time of the explosion, phone services in Texas City were not working because of a telephone operators’ strike. When the operators learned of the accident, they quickly went back to work, but the strike caused an initial delay in coordinating rescue efforts. Once operators began calling for help, rescue workers from all over the area began responding immediately. The U.S. Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marine Reserve and the Texas National Guard all sent personnel, including doctors, nurses and ambulances. The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston sent doctors, nurses, and medical students. Firefighters from Galveston, Houston, Fort Crockett, Ellington Field, and surrounding towns arrived to help. The cities of Galveston, Houston and San Antonio sent policemen to assist the Texas City Police Department in maintaining order after the explosion. The U.S. Army flew in blood  plasma, gas masks, food, and other supplies, provided bull-dozers to begin clearing the wreckage, and set up temporary housing for the survivors at Camp Wallace in Hitchcock. The Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America sent a flood of volunteers who provided first aid, food, water and comfort to city residents. Volunteers from other local organizations, and others who were not part of any organization, felt compelled to help. There was no operational hospital in Texas City at the time of the disaster, so volunteers converted city hall and chamber of commerce buildings into makeshift infirmaries. Many wounded were evacuated to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, the hospital at Fort Crockett, and hospitals in Houston.

plasma, gas masks, food, and other supplies, provided bull-dozers to begin clearing the wreckage, and set up temporary housing for the survivors at Camp Wallace in Hitchcock. The Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America sent a flood of volunteers who provided first aid, food, water and comfort to city residents. Volunteers from other local organizations, and others who were not part of any organization, felt compelled to help. There was no operational hospital in Texas City at the time of the disaster, so volunteers converted city hall and chamber of commerce buildings into makeshift infirmaries. Many wounded were evacuated to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, the hospital at Fort Crockett, and hospitals in Houston.

Leave a Reply