When we think of our nation’s early wars, and really, up until the Persian Gulf War, soldiers were officially men only. Prior to the Persian Gulf War, any women who were in combat were disguised as men, or they were in non-combat roles, such as support staff and nurses. Few women were recognized for their service, much less honored for it, but on March 12, 1776, in Baltimore, Maryland, someone decided to change the way we looked at the effort made by women in wars. And when I say effort know that I include much sacrifice.

When we think of our nation’s early wars, and really, up until the Persian Gulf War, soldiers were officially men only. Prior to the Persian Gulf War, any women who were in combat were disguised as men, or they were in non-combat roles, such as support staff and nurses. Few women were recognized for their service, much less honored for it, but on March 12, 1776, in Baltimore, Maryland, someone decided to change the way we looked at the effort made by women in wars. And when I say effort know that I include much sacrifice.

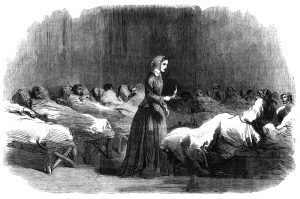

That day, a public notice appeared in local papers recognizing the sacrifice of women to the cause of the revolution. The notice urged others to recognize women’s contributions as well, and announced, “The necessity of taking all imaginable care of those who may happen to be wounded in the country’s cause, urges us to address our humane ladies, to lend us their kind assistance in furnishing us with linen rags and old sheeting, for bandages.” On and off the battlefield, women were known to support the revolutionary cause by providing nursing assistance. But donating bandages and sometimes applying them was only one form of aid provided by the women of the new United States. From the earliest protests against British taxation, women’s assent and labor  was critical to the success of the cause. The boycotts that united the colonies against British taxation required female participation far more than male participation, in fact, the men designing the non-importation agreements chose to boycott products used mostly by women…how thoughtful of them!!

was critical to the success of the cause. The boycotts that united the colonies against British taxation required female participation far more than male participation, in fact, the men designing the non-importation agreements chose to boycott products used mostly by women…how thoughtful of them!!

Tea and cloth are perhaps the best examples of these boycotted products. While most schoolchildren have read of the men who dressed as Mohawk Indians and dumped large volumes of tea into Boston Harbor at the Boston Tea Party, as a form of opposition to the hated Tea Act, few realize that women…not men…drank most of the tea in colonial America. Samuel Adams and his friends may have dumped the tea in the harbor, but they were far more likely to drink rum than tea when they returned to their homes. Conveniently, their actions actually deprived their wives, mothers, sisters and daughters, and not themselves. The colonists only resorted to an attempted boycott of rum in 1774, after Britain had closed the port of Boston. I guess it was time for drastic measures.

Similarly, when John Adams and other men in power thought it best to stop importing fine British fabrics with  which to make their clothing during the protests of the late 1760s, it had little impact on their daily lives. Wearing homespun cloth may not have been as comfortable nor look as refined as their regular clothing, but it was Abigail and other colonial wives and homemakers, not John and his fellow men, who were forced to spend hours spinning clothes to create their families’ wardrobes. Thus, in 1776, when Abigail begged John to remember the ladies while drafting the U.S. Constitution, she was not begging a favor, but demanding payment of an enduring debt. And her husband, in good conscience could not deny her right, or her important request.

which to make their clothing during the protests of the late 1760s, it had little impact on their daily lives. Wearing homespun cloth may not have been as comfortable nor look as refined as their regular clothing, but it was Abigail and other colonial wives and homemakers, not John and his fellow men, who were forced to spend hours spinning clothes to create their families’ wardrobes. Thus, in 1776, when Abigail begged John to remember the ladies while drafting the U.S. Constitution, she was not begging a favor, but demanding payment of an enduring debt. And her husband, in good conscience could not deny her right, or her important request.

Leave a Reply