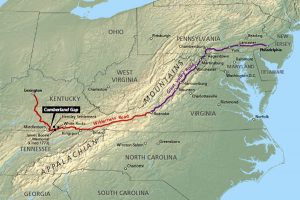

In 1775, Daniel Boone blazed a trail through the Cumberland Gap…a notch in the Appalachian Mountains located near the intersection of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee…through the interior of Kentucky and to the Ohio River. That might not seem like such a big deal, but the trail, which became known as the Wilderness Road, would serve as the pathway to the western United States for some 300,000 settlers over the next 35 years. The path that Boone pioneered led to the establishment of the first settlements in Kentucky, including Boonesboro; and to Kentucky’s admission to the Union as the 15th state in 1792. Of course, Daniel Boone wasn’t the first human being to ever use the trail. The earliest origins of the Wilderness Road were the trails, created by the great herds of buffalo that once roamed the region. Then came the Native American tribes such as the Cherokee and Shawnee, who used the trails to make attacks on each other. They called the trail the Athowominee, which means “Path of the Armed Ones” or “The Great Warrior’s Path.” In 1673, a young man named Gabriel Arthur, became the first white settler known to have crossed through the Cumberland Gap using part of what would become the Wilderness Road. Of course, it wasn’t his choice to go. The Shawnee warriors captured Arthur and forced him to go with them, before releasing him later. I’m quite sure he would have gladly forgone the honor of being the first white man on the trail, if it meant that he would not be taken prisoner.

In 1775, Daniel Boone blazed a trail through the Cumberland Gap…a notch in the Appalachian Mountains located near the intersection of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee…through the interior of Kentucky and to the Ohio River. That might not seem like such a big deal, but the trail, which became known as the Wilderness Road, would serve as the pathway to the western United States for some 300,000 settlers over the next 35 years. The path that Boone pioneered led to the establishment of the first settlements in Kentucky, including Boonesboro; and to Kentucky’s admission to the Union as the 15th state in 1792. Of course, Daniel Boone wasn’t the first human being to ever use the trail. The earliest origins of the Wilderness Road were the trails, created by the great herds of buffalo that once roamed the region. Then came the Native American tribes such as the Cherokee and Shawnee, who used the trails to make attacks on each other. They called the trail the Athowominee, which means “Path of the Armed Ones” or “The Great Warrior’s Path.” In 1673, a young man named Gabriel Arthur, became the first white settler known to have crossed through the Cumberland Gap using part of what would become the Wilderness Road. Of course, it wasn’t his choice to go. The Shawnee warriors captured Arthur and forced him to go with them, before releasing him later. I’m quite sure he would have gladly forgone the honor of being the first white man on the trail, if it meant that he would not be taken prisoner.

Another expedition, led by Dr Thomas Walker set out in 1750, from Virginia with the aim of exploring lands further west for potential settlement. Discouraged by the rough terrain in southeastern Kentucky, the group turned back, but Walker’s detailed report of the expedition proved to be an invaluable resource for later expeditions, including Boone’s. Having hiked some pretty tough trails, I can say that I can understand the idea of turning back. I’ve never turned back on a trail, but then I’m not camping out on my trails either. Freezing cold in the nights and searing heat in the daytime, could make for a very rough trip.

In 1773, Boone attempted to lead his family and several others to settle in Kentucky, but Cherokee Indians attacked the group, and two of the would-be settlers, including Boone’s son James, were killed. Two years later, a group of wealthy investors headed up by Judge Richard Henderson of North Carolina formed the Transylvania Company, to colonize the rich lands around the Kentucky River and establish Kentucky as the 14th colony. They decided to hire Boone, who’s knowledge of the existing trails was well known, to blaze a new trail through the Cumberland Gap. Henderson decided to approach the Cherokee directly, and in March 1775 his associates negotiated with the Cherokee to purchase the land between the Cumberland and Kentucky rivers, a total of some 20 million acres, for 10,000 pounds of goods.

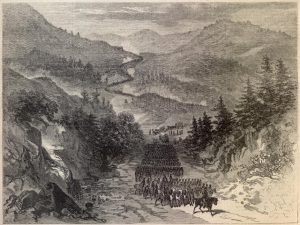

On March 10, 1775, Boone and around 30 other ax-wielding road cutters, including his brother and son-in-law, set off from the Long Island of Holston River, a sacred Cherokee treaty site located in present day Kingsport, Tennessee. From there they traveled north along a portion of the Great Warrior’s Path, heading through Moccasin Gap in the Clinch Mountains. They Avoided Troublesome Creek, which had plagued previous travelers along the route, and crossed the Clinch River, near what is now Speers Ferry, Virginia. Then they followed Stock Creek, crossed Powell Mountain through Kane’s Gap and headed into the Powell River Valley. About 20 miles from the Cumberland Gap, Boone and his party rested at Martin’s Station, a settlement near what is now Rose Hill, Virginia that had been founded by Joseph Martin in 1769. After a Native American attack, Martin and

his fellow settlers had abandoned the region, but they had returned in early 1775 to build a more permanent settlement. Just before reaching their intended settlement site on the Kentucky River in late March, Boone’s group was attacked by some of the Shawnee. They had not ceded their right to Kentucky’s land, like the Cherokee. Most of Boone’s men were able to escape, but a few were killed or injured. In April, the group finally arrived on the south side of the Kentucky River, in what is now Madison County, Kentucky.

his fellow settlers had abandoned the region, but they had returned in early 1775 to build a more permanent settlement. Just before reaching their intended settlement site on the Kentucky River in late March, Boone’s group was attacked by some of the Shawnee. They had not ceded their right to Kentucky’s land, like the Cherokee. Most of Boone’s men were able to escape, but a few were killed or injured. In April, the group finally arrived on the south side of the Kentucky River, in what is now Madison County, Kentucky.

Leave a Reply