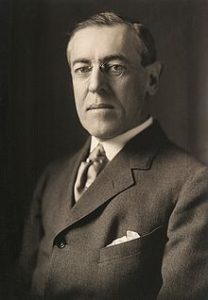

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

The non-stop German offensive continued to take its toll throughout the month of April, however, because the majority of American troops in Europe, who were now arriving at a rate of 120,000 a month, were still not sent into battle. In a meeting of the Supreme War Council of Allied leaders at Abbeville, near the coast of the English Channel, which began on May 1, 1918, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and General Ferdinand Foch, the recently named Generalissimo of all Allied forces on the Western Front, was trying hard to persuade Pershing to send all the existing American troops to the front at once. Pershing resisted, reminding the group that the United States had entered the war “independently” of the other Allies, and indeed, the United States would insist during and after the war on being known as an “associate” rather than a full-fledged ally. He further stated, “I do not suppose that the American army is to be entirely at the disposal of the French and British commands.” I’m sure his remarks brought with them, much concern.

On May 2, the second day of the meeting, the debate continued, with Pershing holding his ground in the face of  heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

Leave a Reply