World War II

I had never heard the expression, “war sand” before, but when I think about it, the presence of it makes perfect sense. It would be impossible to have any kind of a battle and not leave behind spent bullets, as well as bits of shrapnel from bombs littering the battlefield. In the case of the D-Day Battle, there were more that 5,000 tons of bombs that littered the beaches of Normandy. The beaches were literal chaos, and it was all they could do to rescue the wounded, recover the bodies, and remove the equipment, much less save bits of metal and spent bullets left behind. On D-Day, more than 5,000 tons of bombs were dropped by the Allies on the Axis powers as part of the prelude to the Normandy landings…and then there was the bullets and such that hit the beaches during the battle.

I had never heard the expression, “war sand” before, but when I think about it, the presence of it makes perfect sense. It would be impossible to have any kind of a battle and not leave behind spent bullets, as well as bits of shrapnel from bombs littering the battlefield. In the case of the D-Day Battle, there were more that 5,000 tons of bombs that littered the beaches of Normandy. The beaches were literal chaos, and it was all they could do to rescue the wounded, recover the bodies, and remove the equipment, much less save bits of metal and spent bullets left behind. On D-Day, more than 5,000 tons of bombs were dropped by the Allies on the Axis powers as part of the prelude to the Normandy landings…and then there was the bullets and such that hit the beaches during the battle.

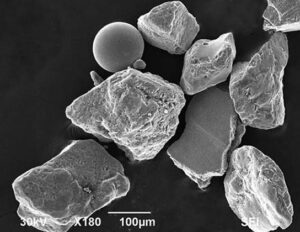

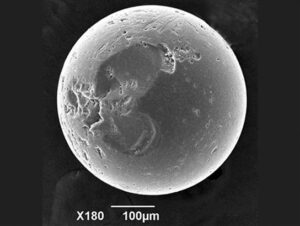

These days, scientists estimate that 4% of the Normandy beaches are made up of shrapnel from the D-Day Landings. They have studied the sand on the beaches of Normandy, and they’ve found microscopic bits of smoothed-down shrapnel from the landings. The sand on the Normandy beaches is known as “war sand,” which is defined as “sand that is a result from wartime operations.” I had heard of beaches that are made of glass that has been rubbed smooth by the water against the ground, but I hadn’t ever thought about the water being able to smooth the sharp bits of shrapnel to make them smooth. Nevertheless, the beaches of Normandy are  covered in a fine dust created from particles deposited there during or right before the D-Day operations of World War II. The grains are hidden among the beaches of the Normandy. It makes me wonder how many other beaches have shrapnel and bullets as a secret part of their makeup.

covered in a fine dust created from particles deposited there during or right before the D-Day operations of World War II. The grains are hidden among the beaches of the Normandy. It makes me wonder how many other beaches have shrapnel and bullets as a secret part of their makeup.

Earle McBride, a geologist from the University of Texas at Austin, figures the sands shrapnel level at 4%. That doesn’t seem like much, but considering the years since D-Day, and the number of people who have walked those beaches, possibly looking for closure concerning lost loved ones, 4% is quite a bit. One might wonder how he could have come to that conclusion, but apparently the sand-sized fragments of steel are magnetic, making them easily discernible under a microscope. Of course, there are still relics from the battle. The artificial landscape of eroded machinery is still detectable using special instruments in the coastal dunes.

The shrapnel content of the beaches will eventually disappear. It is estimated that at the present rate of deterioration, the magnetic particles will probably be wiped from the sands in another 100 years. The shrapnel is subject to waves, storms, and rust, which will wipe these spherical magnetic shards from the coasts.  Strangely, Earle McBride didn’t set out to find these shards, but a visit to Omaha Beach in 1988 resulted in the discovery of these tiny remnants of shrapnel. I wonder how he noticed the shrapnel. Oddly, the shards were collected 20 years ago and only analyzed recently. Why did it take so long to examine them? Of course, I have answered my own question. While he may have known what he had, it is possible that he really didn’t or at least didn’t know the significance of what he had. He might have simply collected the sand as a keepsake of his visit. Nevertheless, upon examination, the samples revealed that the jagged-edged grains had a metallic sheen and a rust-colored coating. The angular grains proved to be magnetic…they proved to be shrapnel from that long ago battle.

Strangely, Earle McBride didn’t set out to find these shards, but a visit to Omaha Beach in 1988 resulted in the discovery of these tiny remnants of shrapnel. I wonder how he noticed the shrapnel. Oddly, the shards were collected 20 years ago and only analyzed recently. Why did it take so long to examine them? Of course, I have answered my own question. While he may have known what he had, it is possible that he really didn’t or at least didn’t know the significance of what he had. He might have simply collected the sand as a keepsake of his visit. Nevertheless, upon examination, the samples revealed that the jagged-edged grains had a metallic sheen and a rust-colored coating. The angular grains proved to be magnetic…they proved to be shrapnel from that long ago battle.

When Switzerland found itself in the middle of an unusual heatwave, the Gauli Glacier melted enough to uncover the wreckage debris of an American World War II plane that crash-landed in the Bernese Alps 72 years ago. Now, when you hear about the crash of a plane, especially into a mountain or in this case, a glacier, you expect to find fatalities. Of course, this plane crashed a long time ago, and the authorities already knew the outcome of that crash. The people who found the plane in the ice, however, might not have. This plane, a C-53 Skytrooper Dakota had been traveling from Austria to Italy when it collided with the Gauli Glacier at an altitude of 10,990 feet on that fateful day.

When Switzerland found itself in the middle of an unusual heatwave, the Gauli Glacier melted enough to uncover the wreckage debris of an American World War II plane that crash-landed in the Bernese Alps 72 years ago. Now, when you hear about the crash of a plane, especially into a mountain or in this case, a glacier, you expect to find fatalities. Of course, this plane crashed a long time ago, and the authorities already knew the outcome of that crash. The people who found the plane in the ice, however, might not have. This plane, a C-53 Skytrooper Dakota had been traveling from Austria to Italy when it collided with the Gauli Glacier at an altitude of 10,990 feet on that fateful day.

It was November 19, 1946, and the plane carrying four crew members and eight passengers were enjoying their trip, when something went terribly wrong. When they hit the glacier, several people were injured, amazingly, there were no fatalities. Among the passengers were high-ranking United States service members traveling with relatives…four women and one 11-year-old girl. Now, they found themselves high up on a glacier, and it was likely very cold. They were stuck at the crash site for six days before rescuers found them and could

get to them. They were forced to drink snow water and ration chocolate bars to survive, but survive they did. Many times, survival at a crash site, if you survived the initial crash, is all about using common sense and keeping your wits about you. You have to take stock of your supplies and be willing to ration what you have. You can’t let anyone get out of control, because a panic could waste vital supplies. Water is the most vital of the supplies, because while the human body can go weeks without food, it can only live a few days without water. While it would seem that water on a glacier would be plentiful, it may not be so. You would have to chip away at the ice, and then melt it to drink. In addition, you have to get it warm, or you will risk the water causing Hypothermia. This particular group managed to do things right, or at least enough right to survive the six days while they waited for rescue. Once rescued, they went on with their lives feeling very blessed to be alive.

get to them. They were forced to drink snow water and ration chocolate bars to survive, but survive they did. Many times, survival at a crash site, if you survived the initial crash, is all about using common sense and keeping your wits about you. You have to take stock of your supplies and be willing to ration what you have. You can’t let anyone get out of control, because a panic could waste vital supplies. Water is the most vital of the supplies, because while the human body can go weeks without food, it can only live a few days without water. While it would seem that water on a glacier would be plentiful, it may not be so. You would have to chip away at the ice, and then melt it to drink. In addition, you have to get it warm, or you will risk the water causing Hypothermia. This particular group managed to do things right, or at least enough right to survive the six days while they waited for rescue. Once rescued, they went on with their lives feeling very blessed to be alive.

The snow, and later, ice covered the plane as the years went by, and it was very likely forgotten…until 2012 anyway, when three young people discovered the plane’s propeller on the glacier. They continued to observe the emerging plane and as the glacier continued to melt, the scene unfolded. Today, it reportedly looks like a

field covered in plane debris, and many people probably wonder how anyone managed to live through the initial crash…much less everyone. As the glacier melted, the plane slid down the mountainside and was expected to finally emerge at the bottom. In fact, much of the debris field might actually be caused by the melting ice.

field covered in plane debris, and many people probably wonder how anyone managed to live through the initial crash…much less everyone. As the glacier melted, the plane slid down the mountainside and was expected to finally emerge at the bottom. In fact, much of the debris field might actually be caused by the melting ice.

New safety laws usually come about as a direct result of a disaster or some other traumatic event. Such was the case with the laws formed after the fire and subsequent sinking of SS Yarmouth Castle. The ship was originally built as Evangeline, and it was an American steamship. It was the second of two identical ships built by the William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Company for the Eastern Steamship Lines for service on the New York City to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia route, operating in practice out of Boston as well. As with many ships, Evangeline was pulled into service during World War II and turned over to the War Shipping Administration, which operated all oceangoing vessels for the United States. During its war years, it was used primarily as an army troop transport. On July 1, 1946, after the war was over, Eastern Steamship Lines resumed control of the ship. Following its war service, it was put back in normal service for a short period and then, the ship was laid up. In 1954, it was sold and put under Liberian registry, operating from Boston to Nova Scotia, then to the Caribbean. In 1963 Evangeline was sold again, put under Panamanian registry. Then, it was renamed SS Yarmouth Castle. It was operated by Yarmouth Cruise Lines between Miami and Nassau, Bahamas, from 1964 until the disaster on November 13, 1965.

New safety laws usually come about as a direct result of a disaster or some other traumatic event. Such was the case with the laws formed after the fire and subsequent sinking of SS Yarmouth Castle. The ship was originally built as Evangeline, and it was an American steamship. It was the second of two identical ships built by the William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Company for the Eastern Steamship Lines for service on the New York City to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia route, operating in practice out of Boston as well. As with many ships, Evangeline was pulled into service during World War II and turned over to the War Shipping Administration, which operated all oceangoing vessels for the United States. During its war years, it was used primarily as an army troop transport. On July 1, 1946, after the war was over, Eastern Steamship Lines resumed control of the ship. Following its war service, it was put back in normal service for a short period and then, the ship was laid up. In 1954, it was sold and put under Liberian registry, operating from Boston to Nova Scotia, then to the Caribbean. In 1963 Evangeline was sold again, put under Panamanian registry. Then, it was renamed SS Yarmouth Castle. It was operated by Yarmouth Cruise Lines between Miami and Nassau, Bahamas, from 1964 until the disaster on November 13, 1965.

On November 12, 1965, Yarmouth Castle departed Miami for Nassau carrying 376 passengers and 176 crew members for a total of 552 people. The ship was due to arrive in Nassau the next day. The captain on the voyage was 35-year-old Byron Voutsinas. Shortly after midnight on November 13, a fire broke out in room 610 on the main deck. Being used as a storage space, the room was filled with mattresses, chairs, and other combustible materials. Unfortunately, the room did not have a sprinkler system, and in the end, the source of the fire could not be determined. It is thought that jury-rigged wiring might have thrown sparks that then entered the room through the ventilation ducts, but simple carelessness was not ruled out either.

A normal patrol went by the room between 12:30am and 12:50am, but they failed to systematically check all areas of the ship and detect the fire. At some point between midnight and 1:00am, the crew and passengers began noticing smoke and heat. Finally, a search was started to find the fire. By the time they discovered it in room 610 and the toilet above that room, it had already begun to spread and attempts to fight the fire with fire extinguishers were useless. Attempts to activate a fire alarm box were also unsuccessful. The bridge was unaware of the fire until about 1:10am, and by that time, Yarmouth Castle was 120 miles east of Miami and 60 miles northwest of Nassau, and in deep trouble. Since the radio room became involved, they were unable to call for help, or even call for the passengers to abandon ship.

The captain proceeded to the lifeboat containing the emergency radio, but he could not reach it. He and several crew members launched another lifeboat and abandoned ship at about 1:45am. The captain later testified that he wanted to reach one of the rescue vessels to make an emergency call. The remaining crew proceeded to alert passengers and attempted to help them escape their cabins. Some passengers tried to escape through cabin windows but couldn’t open them due to improper maintenance. The sprinkler system finally activated but was pretty much ineffective due to the severity of the fire. Crew members attempted to battle the flames with hoses, but they were hampered by low hydrant pressure. The investigation later determined that more valves were open than the pumps could handle.

Some of the lifeboats burned and others could not be launched due to mechanical problems. Only about half of the ship’s boats made it safely away. Passengers near the bow could not reach the lifeboats, but some were later picked up by boats from rescue vessels. The Finnish freighter Finnpulp was just eight miles ahead of Yarmouth Castle, also headed east. That ship’ crew noticed at 1:30am, that Yarmouth Castle had slowed significantly on the radar screen. Looking back, they saw the flames and notified their captain, John Lehto, who had been asleep. Lehto immediately ordered Finnpulp turned around. The Finnpulp successfully contacted the Coast Guard in Miami. It was the first distress call sent out. The passenger liner Bahama Star was following Yarmouth Castle at about twelve miles distance. At 2:15am, Captain Carl Brown noticed rising smoke and a red glow on the water. Realizing that this was Yarmouth Castle, he ordered the ship ahead at full speed. Bahama Star radioed the US Coast Guard at 2:20am.

Though rescue efforts were largely successful, for those who survived, 90 people lost their lives. Yarmouth  Castle capsized onto her port side just before 6:00am and sank at 6:03am. The wreck has not been located but is thought to rest 10,800 feet below the Atlantic. “The Yarmouth Castle disaster prompted updates to the Safety of Life at Sea law, or SOLAS. The updated law brought new maritime safety rules, requiring fire drills, safety inspections, and structural changes to new ships. Under SOLAS, any vessel carrying more than 50 overnight passengers is required to be built entirely of non-combustible materials such as steel. Yarmouth Castle’s largely wooden superstructure was found to be the main cause of the fire’s rapid spread.”

Castle capsized onto her port side just before 6:00am and sank at 6:03am. The wreck has not been located but is thought to rest 10,800 feet below the Atlantic. “The Yarmouth Castle disaster prompted updates to the Safety of Life at Sea law, or SOLAS. The updated law brought new maritime safety rules, requiring fire drills, safety inspections, and structural changes to new ships. Under SOLAS, any vessel carrying more than 50 overnight passengers is required to be built entirely of non-combustible materials such as steel. Yarmouth Castle’s largely wooden superstructure was found to be the main cause of the fire’s rapid spread.”

Vnukovo Airport was experiencing heavy fog on November 5, 1946. Due to the resulting low visibility conditions and a high number of aircraft bound for Moscow, including an Aeroflot LI-2 (registration CCCP-L4181) that was being ferried from Voronezh to Moscow. The LI-2, along with a number of other planes, were put in a holding pattern for 75 minutes. These things are a common practice, but maybe not for so long.

Vnukovo Airport was experiencing heavy fog on November 5, 1946. Due to the resulting low visibility conditions and a high number of aircraft bound for Moscow, including an Aeroflot LI-2 (registration CCCP-L4181) that was being ferried from Voronezh to Moscow. The LI-2, along with a number of other planes, were put in a holding pattern for 75 minutes. These things are a common practice, but maybe not for so long.

Finally, at 5:45pm, local time, the crew of the LI-2 was cleared to land and began their approach, still in a thick fog. It was a difficult approach, and the crew decided to go around. In all, five ADF approaches under radar guidance were attempted. Unfortunately, during the fifth approach the plane suffered fuel exhaustion. Immediately, the plane lost altitude and struck light poles and crashed. Fog creates very unique problems, and to complicate matters, that night three Aeroflot aircraft also crashed near Vnukovo Airport, killing a total of 19 occupants.

The first one, Aeroflot LI-2 (registration CCCP-L4181) crashed near Yamshchina, Moskovskaya, Russia. The determined cause was fuel exhaustion after being in a holding pattern for two hours, killing all five crew on board. Then, an Aeroflot C-47 (registration CCCP-L946) crashed in fog at Vnukovo Airport while attempting a go-around after being in a holding pattern for two hours, killing 13 of the 26 on board. Finally, an Aeroflot LI-2 (registration CCCP-L4207) crashed at Vnukovo Airport after repeated landing attempts due to fuel exhaustion after being in a holding pattern for 75 minutes, killing one of 26 on board.

The Vnukovo Airport is Moscow’s oldest operating airport. Originally opened for military operations during the Second World War, it became a civilian facility after the war. The Soviet government approved its construction in  1937, because the older Khodynka Aerodrome, which was located much closer to the city center, was becoming overloaded. That airport closed by the 1980s. Vnukovo was built by several thousand inmates of Likovlag, which was a Gulag concentration camp created specifically for this purpose. Vnukovo opened on July 1, 1941. While the airport was old, it was not the cause of the November 5, 1946 crashes. More likely the pilots and flight controllers, who were preoccupied with the fog, simply forgot to monitor the fuel levels, and missed the fact that they were dangerously low. It is odd, however, that three were missed at the same time, and very sad that 19 people lost their lives because of it.

1937, because the older Khodynka Aerodrome, which was located much closer to the city center, was becoming overloaded. That airport closed by the 1980s. Vnukovo was built by several thousand inmates of Likovlag, which was a Gulag concentration camp created specifically for this purpose. Vnukovo opened on July 1, 1941. While the airport was old, it was not the cause of the November 5, 1946 crashes. More likely the pilots and flight controllers, who were preoccupied with the fog, simply forgot to monitor the fuel levels, and missed the fact that they were dangerously low. It is odd, however, that three were missed at the same time, and very sad that 19 people lost their lives because of it.

Our government has been known, in its history, to do some things that really were underhanded, and in some cases horrific. The “need” for nuclear bombs naturally facilitated the need for nuclear testing. I think everyone knows that would had to have happened, but on November 1, 1951, the US Army conducted nuclear tests in the Nevada desert that included a “diabolical exercise in which 6500 US Army troops were exposed to the effects of a nearby nuclear detonation and its associated radiation.” When I read that, I was furious. They knew what they were doing, and they did it as an experiment…just to see what would happen to those poor men.

Our government has been known, in its history, to do some things that really were underhanded, and in some cases horrific. The “need” for nuclear bombs naturally facilitated the need for nuclear testing. I think everyone knows that would had to have happened, but on November 1, 1951, the US Army conducted nuclear tests in the Nevada desert that included a “diabolical exercise in which 6500 US Army troops were exposed to the effects of a nearby nuclear detonation and its associated radiation.” When I read that, I was furious. They knew what they were doing, and they did it as an experiment…just to see what would happen to those poor men.

It was called Operation Buster–Jangle. The US Army conducted a series of 7 nuclear tests, that included the November 1st test. In that involuntary one test, the 6500 troops, were dug in foxholes and trenches only 6 miles from an air burst nuclear bomb of 21 kilotons yield. That is about the size of the Nagasaki bomb!! After the soldiers felt the hot nuclear wind blast over them, the wind deposited desert dust in choking clouds upon the men. Then, the soldiers were ordered to get up and march across the blast site to within 900 meters (a little over ½ a mile) of the nuclear “ground zero.” That is incredibly close, and those men were exposed.

The damage done to those men was not well documented, but the US Government later passed the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) to compensate the military veterans exposed to nuclear testing in the 1950’s. The passing of that act is implied acknowledgment of the responsibility of the US government in long term health problems experienced by those troops…without actually placing the blame, and therefore opening the government up to future lawsuits. Basically, the men, were they still alive, or their families, if not,

could theoretically be compensated for their losses. Of course, as many of us have seen with these kinds of cases, the process is very slow, the burden of proof for the men trying to receive compensation is heavy, and the final payout is usually quite low. RECA has awarded over $2.4 billion in benefits to more than 37,000 claimants since its inception in 1990. Still, that’s a small price to pay for the destruction of so many lives.

could theoretically be compensated for their losses. Of course, as many of us have seen with these kinds of cases, the process is very slow, the burden of proof for the men trying to receive compensation is heavy, and the final payout is usually quite low. RECA has awarded over $2.4 billion in benefits to more than 37,000 claimants since its inception in 1990. Still, that’s a small price to pay for the destruction of so many lives.

During World War II, the Third Reich run by Adolf Hitler was at war with the world, but at that point, mostly with the British, and especially the British Royal Family. There were a number of bombing campaigns that devastated London, but it was the attack of September 13, 1940, that managed to hit the mark that Hitler would consider, the jackpot. That bombing managed to hit Buckingham Palace. upon hearing that, I wondered, “Where was the family?” Many people tried to leave London, if they had the means. Many of the children were hidden on the country. The rest of the people hid wherever they could…in places like subway tunnels and such. Pretty much everyone had their windows blacked out at night, so that unless there was a moon, homes were well hidden. That summer the German army ramped up their attacks on Britain. London was the prime target of the pounding by the Luftwaffe. Called “The Blitz” attacks, the bombings were very damaging…destroying much of London’s infrastructure.

During World War II, the Third Reich run by Adolf Hitler was at war with the world, but at that point, mostly with the British, and especially the British Royal Family. There were a number of bombing campaigns that devastated London, but it was the attack of September 13, 1940, that managed to hit the mark that Hitler would consider, the jackpot. That bombing managed to hit Buckingham Palace. upon hearing that, I wondered, “Where was the family?” Many people tried to leave London, if they had the means. Many of the children were hidden on the country. The rest of the people hid wherever they could…in places like subway tunnels and such. Pretty much everyone had their windows blacked out at night, so that unless there was a moon, homes were well hidden. That summer the German army ramped up their attacks on Britain. London was the prime target of the pounding by the Luftwaffe. Called “The Blitz” attacks, the bombings were very damaging…destroying much of London’s infrastructure.

Well, the Royal Family certainly had the means to get out, so I assumed that they were in Scottland or somewhere when all this took place. As the leaders of the country, it would certainly make sense to get them to  safety. Nevertheless, when Buckingham Palace was bombed on September 13, 1940, Queen Elizabeth and King George VI were there. On that morning they were relaxing with a cup of tea, when they heard the ‘unmistakable whirr-whirr of a German plane’ and the ‘scream of a bomb’ that was followed by a rumble and a crash. A German raider had dropped five high explosive bombs on the Palace. The areas hit were the Royal chapel, inner quadrangle, Palace gates, and the Victoria memorial. Four members of the Palace staff were injured, one of whom died. Thankfully, the King and Queen went unharmed in the incident. Queen Elizabeth said in a poignant statement, ‘I am glad we have been bombed. It makes me feel I can look the East-End in the face.’ I’m sure he was just trying to be brave, because they were obviously quite shaken up. Her stance strengthened the reputation of the Royal Family in the eyes of the British public.

safety. Nevertheless, when Buckingham Palace was bombed on September 13, 1940, Queen Elizabeth and King George VI were there. On that morning they were relaxing with a cup of tea, when they heard the ‘unmistakable whirr-whirr of a German plane’ and the ‘scream of a bomb’ that was followed by a rumble and a crash. A German raider had dropped five high explosive bombs on the Palace. The areas hit were the Royal chapel, inner quadrangle, Palace gates, and the Victoria memorial. Four members of the Palace staff were injured, one of whom died. Thankfully, the King and Queen went unharmed in the incident. Queen Elizabeth said in a poignant statement, ‘I am glad we have been bombed. It makes me feel I can look the East-End in the face.’ I’m sure he was just trying to be brave, because they were obviously quite shaken up. Her stance strengthened the reputation of the Royal Family in the eyes of the British public.

This wasn’t the first attempt to take out the palace. Days earlier, on September 8th, a 50-kilogram bomb fell on the grounds of the Palace. That one malfunctioned, and didn’t explode, so it was later destroyed in a controlled explosion. Of course, the British Foreign Office immediately recommended that the family should leave the country for a time after the second bomb did so much damage, they refused, and it was viewed as a deep  “courage and a commitment to the United Kingdom” that the public appreciated. The Queen went on to say that “The children will not leave unless I do. I shall not leave unless their father does, and the King will not leave the country in any circumstances, whatever. So, it was settled. This act of defiance in the face of the German Blitz gave the country a much-needed boost in their war efforts. The people felt like they were not alone, and they gained a sense of unity throughout the United Kingdom. All of this happened during the Battle of Britain, which began on July 10, 1940. I would say that the efforts were greatly increased, because it ended on October 31, 1940, with a British victory.

“courage and a commitment to the United Kingdom” that the public appreciated. The Queen went on to say that “The children will not leave unless I do. I shall not leave unless their father does, and the King will not leave the country in any circumstances, whatever. So, it was settled. This act of defiance in the face of the German Blitz gave the country a much-needed boost in their war efforts. The people felt like they were not alone, and they gained a sense of unity throughout the United Kingdom. All of this happened during the Battle of Britain, which began on July 10, 1940. I would say that the efforts were greatly increased, because it ended on October 31, 1940, with a British victory.

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

So, the Soviet authorities deported German civilians from Germany and Eastern Europe to the USSR after World  War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

The decision was made and the fate of the German people was sealed. In 1946, the Soviet Union forcibly relocated more than 2,500 former Nazi German specialists, including scientists, engineers, and technicians who worked in specialist areas, from companies and institutions relevant to military and economic policy in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany (SBZ) and Berlin, along with around 4,000 family members, totaling more than 6,000 people, to the Soviet Union as war reparations. These specialists with all of their knowledge and abilities, could easily change the course of history in the Soviet Union, or any country they were placed in, for that matter. Still, not all of the forced labor were specialists. Many were unskilled labor, doing menial jobs.

The good thing was that the situation in Germany after World War II was appalling. Many of the people were homeless from the bombings. I suppose that, for that reason, the forced move, while scary, was not the worst thing in the world. It was possible that a new life in the Soviet Union could be favorable when compared to war-torn Germany. It is unclear whether any Germans who were sent to the Soviet Union chose to go back to Germany, because information about forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union was suppressed in the Eastern Bloc until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Many of those records could have also been destroyed.

Bent Faurschou Hviid, who was born January 7, 1921, later became a member of the Danish resistance group Holger Danske during World War II. Because of his red hair, Hviid was nicknamed “Flammen,” which means “The Flame.” In 1951, he and his Resistance partner Jørgen Haagen Schmith, were posthumously awarded the United States Medal of Freedom by President Harry Truman. The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. The award is not limited to US citizens and, while it is a civilian award, it can also be awarded to military personnel and worn on the uniform.

Bent Faurschou Hviid, who was born January 7, 1921, later became a member of the Danish resistance group Holger Danske during World War II. Because of his red hair, Hviid was nicknamed “Flammen,” which means “The Flame.” In 1951, he and his Resistance partner Jørgen Haagen Schmith, were posthumously awarded the United States Medal of Freedom by President Harry Truman. The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. The award is not limited to US citizens and, while it is a civilian award, it can also be awarded to military personnel and worn on the uniform.

If you were to ask the men who were a part of the Holger Danske, they would tell you that no other resistance member was as hated or sought after by the Germans as was Hviid. Leader of the Holger Danske from 1943 through 1945, Gunnar Dyrberg said in the 2003 Danish documentary film, “With a Right to Kill,” that no one knows exactly how many executions “The Flame” performed, but he was rumored to have killed 22 persons. In all, it is said that the Holger Danske carried out an estimated 400 executions…performed by the Resistance agents, but apparently no one man executed more than Hviid.

Hviid grew up during World War I and was 20 when the Germans occupied Denmark. He was not about to just sit back and let the Nazis take over his country…at least, not without a fight. He entered the Holger Danske resistance group in Copenhagen. He was assigned to kill Danish Nazi officials and collaborators…traitors, who in Hviid’s opinion, did not deserve to live.

“Flammen” often partnered with “Citronen” whose real name was Jørgen Haagen Schmith. “Citronen” means “the lemon.” Schmith got this nickname because he sabotaged a Citroën garage, destroying six German cars and a tank. Citronen usually drove for Flammen, who executed their given targets. The two men were the most famous resistance duo in Denmark during World War II. While they often worked together, the Germans put the highest bounty on Flammen’s head that they offered for any Resistance fighter, due to the Faurschou of Germans who were executed by Flammen.

On October 18, 1944, while Hviid was having dinner with his landlady and some other guests, someone knocked at the door. When the door was opened, a German officer demanded entry. Hviid, who was unarmed  that evening, quickly went upstairs seeking to escape across the roof. When he reached the roof, he saw that the house was surrounded. Refusing to be taken alive, Hviid chewed a cyanide capsule and was dead a few seconds later.

that evening, quickly went upstairs seeking to escape across the roof. When he reached the roof, he saw that the house was surrounded. Refusing to be taken alive, Hviid chewed a cyanide capsule and was dead a few seconds later.

The witnesses later told of how they could hear the German soldiers upstairs cheering at the sight of the corpse. For the Germans, the form of death that took “The Flammen” out made no difference to the German soldiers. All that mattered was that he was dead. The soldiers dragged Hviid downstairs feet first, repeatedly causing his head to bang against the stairs as they went. I suppose it was a show of disrespect or perhaps, triumph for them, although they did not cause his death really.

In every army, navy, and air force, there are exceptional soldiers…even among the enemy. During World War II, the German Luftwaffe had an incredible pilot. His name was Erich Rudorffer, and he is credited with shooting down thirteen Soviet aircraft in a single mission on October 11, 1943. In that historic mission while flying an FW-190, Rudorffer downed eight Yak-7s and five Yak-9s of the Soviet Air Force. He eventually shot down 222 enemy aircraft and ended up his combat career flying the Messerschmitt ME-262, the first operational jet fighter.

In every army, navy, and air force, there are exceptional soldiers…even among the enemy. During World War II, the German Luftwaffe had an incredible pilot. His name was Erich Rudorffer, and he is credited with shooting down thirteen Soviet aircraft in a single mission on October 11, 1943. In that historic mission while flying an FW-190, Rudorffer downed eight Yak-7s and five Yak-9s of the Soviet Air Force. He eventually shot down 222 enemy aircraft and ended up his combat career flying the Messerschmitt ME-262, the first operational jet fighter.

Still, it wasn’t just the number of planes he shot down that made him remarkable. It was also the fact that he managed to survive the war despite flying over 1000 missions and being shot down an incredible 16 times. He was even forced to parachute from his stricken fighter planes 9 of those times. Not just a Soviet killer, Rudorffer also shot down 86 aircraft operated by Western Allied air forces. He became a commercial pilot after World War II.

Rudorffer was born on November 1, 1917, in Zwochau, which was a part of the Kingdom of Saxony of the German Empire at that time. Strangely, or maybe not, very little is said or known about his parents. That was typical of the German leadership of that era. They felt like the state, and not the parents should raise the children, because…well, parents had no training in such things. Not that the German leadership did either, but they decided that they knew more than the parents, so they pulled the children from their parents’ homes and put them in boarding schools to “train” them in the German ways. After his graduation from school, Rudorffer received a vocational education as an automobile metalsmith specialized in coachbuilding, which was likely another of the German or “Nazi” way of deciding the course of the lives of the children. He might have stayed a mechanic were it not for World War I. “Rudorffer joined the military service of the Luftwaffe with Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilung 61 (Flier Replacement Unit 61) in Oschatz on April 16, 1936. From September 2 to October 15, 1936, he served with Kampfgeschwader 253 (KG 253—253rd Bomber Wing) and from October16, 1936 to February 24, 1937, he was trained as an aircraft engine mechanic at the Technische Schule Adlershof, the technical school at Adlershof in Berlin. On March 14, 1937, Rudorffer was posted to Kampfgeschwader 153 (KG 153—153rd Bomber Wing), where he served as a mechanic until end October 1938. After that, he was transferred to Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilung 51 (Flier Replacement Unit 51) based at Liegnitz in Silesia, present-day Legnica in Poland, for flight training. Rudorffer was first trained as a bomber pilot and then as a Zerstörer, a heavy fighter or destroyer, pilot. In the winter of 1944 Rudorffer was trained on the ME 262 jet fighter. In February 1945, he was recalled to command I. Gruppe JG 7 “Nowotny” from Major Theodor Weissenberger who replaced Steinhoff as Geschwaderkommodore. Rudorffer claimed 12 victories with the ME 262, to bring his total to 222. His tally  included 136 on the Eastern Front, 26 in North Africa, and 60 on the Western Front including 10 heavy bombers.”

included 136 on the Eastern Front, 26 in North Africa, and 60 on the Western Front including 10 heavy bombers.”

After the war ended, Rudorffer started out flying DC-2s and DC-3s in Australia. Later, he worked for Pan Am and the Luftfahrt-Bundesamt, Germany’s civil aviation authority. Rudorffer was honored as one of the characters in the 2007 Finnish war movie “Tali-Ihantala 1944.” A FW 190 participated, painted in the same markings as Rudorffer’s aircraft in 1944. The aircraft, now based at Omaka Aerodrome in New Zealand, still wears the colors of Rudorffer’s machine. Rudorffer died in April 2016 at the age of 98. At the time of his death, he was the last living recipient of the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords.

What could make a nation go through an earthquake and refuse help from another nation, like the United States? It seems like a strange question, but it is valid. On October 6, 1948, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake leveled Ashgabat, the capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic—now Turkmenistan. The quake killed between 70,000 and 100,000 people. The true number will never be known. In fact, most information of the scope of the disaster remained unknown outside Central Asia until 1973, when archival records were finally unsealed by local officials. So…why seal the records…of an earthquake??

What could make a nation go through an earthquake and refuse help from another nation, like the United States? It seems like a strange question, but it is valid. On October 6, 1948, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake leveled Ashgabat, the capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic—now Turkmenistan. The quake killed between 70,000 and 100,000 people. The true number will never be known. In fact, most information of the scope of the disaster remained unknown outside Central Asia until 1973, when archival records were finally unsealed by local officials. So…why seal the records…of an earthquake??

The town of Ashgabat lies at the foot of the Kopet-Dag Mountain range near the border with Iran. The area is geologically unstable and earthquake prone. That said, why should a large earthquake in an earthquake-prone area need to be hidden? Ashgabat was originally a czarist outpost, founded in 1881. The town grew quickly during World War II, due to evacuees from the war zone. The population grew to an estimated 150,000 people. With a huge influx of people came the need for a lot of new housing, so single-story houses of unreinforced brick and stone, with heavy roofs of packed clay were quickly built, without regard for the need for earthquake proofing. I suppose that was the reason that the authorities didn’t want anyone to come in to help or to know the details of the catastrophe or the number of victims. The schools, hospitals, and other public buildings were built in the same shoddy way. It was wartime, so it may have been that supplies were scarce, or that proper time was not spent on the construction. Of course, less was known about how earthquakes affect buildings too, and even though there were existing seismic standards, they were seldom met. The builders greatly underestimated the earthquake danger, and that was a fact. A 1929 quake had already caused significant property damage, but strangely, the fault zone had been unusually inactive. I suppose this could have been a warning sign. When it is overdue, it may be a sign of an impending catastrophe.

In this case, that was exactly what happened. On October 6, 1948, at 1:17am, with few people awake. Suddenly, they an ominous rumbling from the mountains, followed immediately by violent vertical shaking. It was actually two strong shocks seconds apart, and just as suddenly, Ashgabat was reduced to rubble. There was no escape…there was no time for escape. The buildings were standing one second and collapsed the next. The thing that is the most shocking was that many of the survivors, who had been conditioned by propaganda in the acute early phase of the Cold War, thought that the city had been hit by an American atomic bomb. And the government did nothing to correct their misguided thinking. So, the country did not seek help from the United States.

As suddenly as it had occurred, the quake severed all communications with the outside world. There were no emergency centers, because hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies lay in ruins. The few remaining uninjured rescue workers, members of the city’s emergency services struggled in the darkness to help the injured. Doctors, many of whom had served in the war, pulled equipment from the ruins to set up an emergency station in Karl Marx Square. Finally, by the afternoon, reinforcements and supplies began to arrive from Tashkent and Baku. Nevertheless, the number of casualties, and the inherent difficulty of evacuating gravely wounded people, meant that help came too late for many. It was estimated that half of an estimated thirty thousand people who  had life-threatening injuries died from lack of early treatment…many people died before they could even be pulled from the rubble.

had life-threatening injuries died from lack of early treatment…many people died before they could even be pulled from the rubble.

While the city workers immediately ran to the damaged central headquarters of the Communist Party, where they were told by the party’s first secretary, S Batirova to take an undamaged automobile and head northward to a functioning telephone line, and soldiers stationed at the airport used an aircraft radio to contact Baku and Sverdlovsk, it was still many hours before any details reached areas from which aid could be dispatched.Unfortunately, that wasn’t much help either, because the railway station was in ruins, tracks were blocked, the airport control tower was destroyed, and the airport and roads could not handle heavy traffic. It would take hours and even days, to get the much-needed rescue support the city needed.

Of course, because of the misguided concept that the Americans were somehow involved, the precise death toll will never be known for sure. Estimates range from a shockingly low number of 400, suggested by Nature magazine in 1948, to a more likely number of 110,000. The dead were buried in mass graves. They were not counted or identified, adding to the confusion. There were roughly 50,000 survivors in a city that had previously had a population of approximately 150,000. That suggests that a death toll of 80,000 to 100,000, or about two-thirds of the population is a more accurate number.

The death toll was enormous, and that could have also accounted for the lack of emergency workers. It’s highly likely that many of them were among the dead or injured…not to mention the fact that there may have been a gross shortage of qualified rescue workers in the poorest part of a country, which was just still recovering from long years of war, but the poor response from the rest of the Soviet Union became more and more unconscionable. On October 7, Pravda printed a brief article stating only that “geologists at the Russian Academy of Sciences had detected a strong earthquake.” The article also reported that there were supply shipments and of the evacuation of the wounded, but no mention of the scope of devastation or the number of casualties. Of course, the international press used Pravda’s limited and incorrect reportage about the quake as the source for their own news reports.

To make matters worse, a conspiracy of silence followed the destruction of Ashgabat. Most history books and almanacs of natural disasters actually omit the quake entirely!! In the typical Soviet propaganda style of the 1950’s, they actually praised the severely lacking reconstruction efforts that completely ignored seismological standards. One Soviet journalist who visited the city in 1953, later described being “forbidden to photograph the omnipresent ruins or to report a march of weeping survivors to the mass graves on the outskirts of the city.” Little was known about the devastating earthquake until 1973. Only on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the event, did officials in Turkmenistan begin to open sealed archives and acknowledge the terrible calamity. Why was this? It was largely because of the Cold War, when both sides were eager not to expose their strategic vulnerabilities. That still doesn’t make sense, however, because the destruction of Ashgabat neither compromised the Soviet Union’s defense system nor revealed grave internal weaknesses. The forced silence did nothing to improve domestic morale in Russia, and it created widespread resentment in Central Asia.  Internationally the Soviet Union could have gained propaganda points by publicizing the disaster and then criticizing the lack of response from the West, but for some reason, they didn’t so that either. Of course, the people in the Soviet Union lived in fear of Joseph Stalins sweeping purges and force silence and timidity. They didn’t dare speak of any kind of vulnerability. Until Stalin’s death in 1953, even referencing the event was considered a dangerous move. Financial aid was still desperately needed decades after the disaster, yet it still didn’t really come. Silence translated into slow reconstruction. Substantial portions of the city remain in ruins, and a significant portion of the population still lives in temporary, or inadequate and unsafe, dwellings to this day.

Internationally the Soviet Union could have gained propaganda points by publicizing the disaster and then criticizing the lack of response from the West, but for some reason, they didn’t so that either. Of course, the people in the Soviet Union lived in fear of Joseph Stalins sweeping purges and force silence and timidity. They didn’t dare speak of any kind of vulnerability. Until Stalin’s death in 1953, even referencing the event was considered a dangerous move. Financial aid was still desperately needed decades after the disaster, yet it still didn’t really come. Silence translated into slow reconstruction. Substantial portions of the city remain in ruins, and a significant portion of the population still lives in temporary, or inadequate and unsafe, dwellings to this day.