immigrant

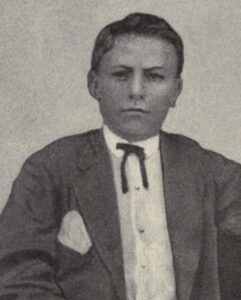

Charles Angelo “Charlie” Siringo didn’t set out to be a lawman, a detective, or a bounty hunter, but the circumstances of his life put him in places where things just fell into place to bring his future into being. Born on February 7, 1855, on the Matagorda Peninsula in Matagorda County, Texas. His mother was an Irish immigrant, and his father was an Italian immigrant from Piedmont. His father died when Siringo was a year old. Siringo attended public school until the start of the American Civil War. In 1867, when he was just 12 years old, Siringo took his first cowpuncher lessons, before moving to Saint Louis after his mother remarried.

Charles Angelo “Charlie” Siringo didn’t set out to be a lawman, a detective, or a bounty hunter, but the circumstances of his life put him in places where things just fell into place to bring his future into being. Born on February 7, 1855, on the Matagorda Peninsula in Matagorda County, Texas. His mother was an Irish immigrant, and his father was an Italian immigrant from Piedmont. His father died when Siringo was a year old. Siringo attended public school until the start of the American Civil War. In 1867, when he was just 12 years old, Siringo took his first cowpuncher lessons, before moving to Saint Louis after his mother remarried.

Siringo attended Fisk public school for a while in New Orleans, but school wasn’t really of interest to him, so he started work as a cowboy for Abel Head “Shanghai” Pierce in April 1871, after returning to Texas. He was just 16 years old, and yet he had done more in his short lifetime that most people would have dreamed of doing. And yet, that was just the beginning. In July 1877, Siringo was in Dodge City, Kansas, where he survived an encounter with Bat Masterson.

Then, Siringo started working for the LX Ranch working as a cattle drive cowboy. This was an unusual kind of cattle drive job, in that it also entailed chasing after LX cattle stolen by Billy the Kid in 1880. By 1884, Siringo  was married Mamie and he quit working for LX Ranch. He opened a tobacco store in Caldwell, Kansas. He and Mamie had a daughter named Viola, born on February 28, 1885. At this point, it seemed prudent to find a safer kind of work, so he began writing his autobiography, “A Texas Cow Boy; Or Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony.” A year later, it was published and well received. Siringo moved his family to Chicago in the spring of 1886 for publication of a second printing.

was married Mamie and he quit working for LX Ranch. He opened a tobacco store in Caldwell, Kansas. He and Mamie had a daughter named Viola, born on February 28, 1885. At this point, it seemed prudent to find a safer kind of work, so he began writing his autobiography, “A Texas Cow Boy; Or Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony.” A year later, it was published and well received. Siringo moved his family to Chicago in the spring of 1886 for publication of a second printing.

In 1886, Siringo witnessed the Chicago Haymarket affair. “The Haymarket affair (also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, or the Haymarket Square riot) was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It began as a peaceful rally in support of workers striking for an eight-hour workday, the day after police killed one and injured several workers. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at the police as they acted to disperse the meeting, and the bomb blast and ensuing gunfire caused the deaths of seven police officers and at least four civilians; dozens of others were wounded.”

Seeing all that destruction prompted Siringo to join the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. He used gunman Pat Garrett’s name as a reference to get the job, having met Garrett in 1880, when they were searching for Billy the Kid. Siringo was hired immediately, and assigned to Denver, reporting to James McParland. He moved his family to Denver, where his wife died in 1890, leaving him with his young daughter to raise. Eventually she went to live with his wife’s aunt and her husband, Emma and Will F Read. Siringo was then assigned several  cases, which took him as far north as Alaska, for the Treadwell mine, and as far south as Mexico City. Using a relatively new technique at the time, he began operating under cover as Charles L Carter and infiltrated gangs of robbers and rustlers, making more than 100 arrests.

cases, which took him as far north as Alaska, for the Treadwell mine, and as far south as Mexico City. Using a relatively new technique at the time, he began operating under cover as Charles L Carter and infiltrated gangs of robbers and rustlers, making more than 100 arrests.

Siringo had a difficult married life, following his first wife’s death. It makes you wonder if he would have stayed married, had she lived. A second marriage in 1893 to Lillie Thomas ended in divorce after three years. They had a son named William Lee Roy. After the divorce, Lillie took their son and moved to Los Angeles. Two other marriages, one in 1907 to a woman named Grace and one in 1913 to a woman named Ellen Partain. Each of these lasted only a few months. Finally, Siringo moved to California to be closer to his children. In the end, it wasn’t his cowboy years or his detective years that really made Siringo famous, but rather his writing. Siringo was the author of seven books. Siringo died on October 28, 1928, in Altadena, California.

Fire safety measures have vastly improved over the years, but in the early 1900s, no such safety measures existed. That would prove deadly on March 25, 1911 in New York City. People didn’t really know about materials that were more flammable, other than wood. Nevertheless, wood was the main material used in buildings, and in fact, still is today. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory was owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. It was located in the top three floors of the Asch Building, on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, in Manhattan. These days that is not really a place we would expect to see a factory…much less a sweatshop, but the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory was a true sweatshop. They employed mostly young immigrant women who worked in a cramped space at lines of sewing machines. Nearly all the workers were teenaged girls who did not speak English and made only about $15 per week working 12 hours a day, every day.

Fire safety measures have vastly improved over the years, but in the early 1900s, no such safety measures existed. That would prove deadly on March 25, 1911 in New York City. People didn’t really know about materials that were more flammable, other than wood. Nevertheless, wood was the main material used in buildings, and in fact, still is today. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory was owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. It was located in the top three floors of the Asch Building, on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, in Manhattan. These days that is not really a place we would expect to see a factory…much less a sweatshop, but the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory was a true sweatshop. They employed mostly young immigrant women who worked in a cramped space at lines of sewing machines. Nearly all the workers were teenaged girls who did not speak English and made only about $15 per week working 12 hours a day, every day.

In 1911, the Asch Building had four elevators with access to the factory floors, but only one was fully operational and the workers had to file down a long, narrow corridor in order to reach it. There were also two stairways down to the street, but one was locked from the outside to prevent stealing and the door of the other only opened inward. The fire escape was so narrow that it would have taken hours for all the workers to use it, even in the best of circumstances…in an emergency, it was almost useless. Pretty much everyone knew about the danger of fire in factories like the Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory, but high levels of corruption in both the garment industry and city government ensured that no useful precautions were taken to prevent fires. The  problem was that making the factories safe cost money, and dug into the profits, so the owners didn’t want to do what was necessary to save lives. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory’s owners were known to be particularly anti-worker in their policies and had played a critical role in breaking a large strike by workers the previous year.

problem was that making the factories safe cost money, and dug into the profits, so the owners didn’t want to do what was necessary to save lives. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory’s owners were known to be particularly anti-worker in their policies and had played a critical role in breaking a large strike by workers the previous year.

On March 25, a Saturday afternoon, there were 600 workers at the factory when a fire began in a rag bin. The manager attempted to use the fire hose to extinguish it, but was unsuccessful. The hose was rotted and its valve was rusted shut. They were at the mercy of the raging inferno. The fire grew and the workers panicked. They tried to exit the building by the elevator, but it could only hold 12 people and the operator was able to make just four trips before it broke down due to the heat and flames. In a desperate attempt to escape the flames. The girls left behind waiting for the elevator plunged down the shaft to their deaths. The girls who fled by way of the stairwells also met awful fates. When they found a locked door at the bottom of the stairs, many were burned alive. In all, 145 workers between the ages of 14 and 43, mostly women and mostly in their teens and early twenties, died that day. Six of them would not be identified until February, 2011…100 years later.

Once the fire was reported, the firefighters tried to put it out, but their ladders would only reach the seventh floor. The fire was on the eighth floor. When escape was proven to be impossible, the girls, desperate to escape the searing heat and flames, began to jump. The bodies of those who jumped landed on the hoses, hampering the flow. The firemen got out nets to catch the girls, but they jumped three at a time, tearing the nets. The nets were of no real help. Within 18 minutes, it was all over. Of the dead, 49 workers had burned to death or been suffocated by smoke, 36 were dead in the elevator shaft and 58 died from jumping to the sidewalks. Two  more died later from their injuries. The workers’ union set up a march on April 5 on New York’s Fifth Avenue to protest the conditions that had led to the fire. It was attended by 80,000 outraged people. Despite a good deal of evidence that the owners and management had been horribly negligent in the fire, a grand jury failed to indict them on manslaughter charges. The tragedy did result in some good, however. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union was formed in the aftermath of the fire and the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law was passed in New York that October. Both were crucial in preventing similar disasters in the future. Still, I think that it will take the memory of the victims of corruption to ever really inspire people to change the way things are.

more died later from their injuries. The workers’ union set up a march on April 5 on New York’s Fifth Avenue to protest the conditions that had led to the fire. It was attended by 80,000 outraged people. Despite a good deal of evidence that the owners and management had been horribly negligent in the fire, a grand jury failed to indict them on manslaughter charges. The tragedy did result in some good, however. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union was formed in the aftermath of the fire and the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law was passed in New York that October. Both were crucial in preventing similar disasters in the future. Still, I think that it will take the memory of the victims of corruption to ever really inspire people to change the way things are.

Recently, my interest turned to the ancestry of the Schulenberg side of my family, when I was contacted by a more famous member of the family, who I will not name at this point, as I have not asked his permission to do so, and so I will respect his privacy. He wondered if we might be related, and I told him that I expected that we probably are. Since that time, I have been looking back on that side of the family. I knew that our side of the Schulenberg family came to America aboard the SS Moltke in 1895, when Max Heinrich Johann Carl Schulenberg arrived on that ship at the tender age of 17 years, without an adult to accompany him…a bold move for a young man. He arrived in New York City, like so many other immigrants. Before too long he had made his way to Blair,Nebraska, where he met and married Julia Doll on December 16, 1902. The couple would have ten children, the oldest of which was Andrew, my husband, Bob’s grandfather. The family would eventually settle in Forsyth, Montana, where there are still family members living to this day.

Recently, my interest turned to the ancestry of the Schulenberg side of my family, when I was contacted by a more famous member of the family, who I will not name at this point, as I have not asked his permission to do so, and so I will respect his privacy. He wondered if we might be related, and I told him that I expected that we probably are. Since that time, I have been looking back on that side of the family. I knew that our side of the Schulenberg family came to America aboard the SS Moltke in 1895, when Max Heinrich Johann Carl Schulenberg arrived on that ship at the tender age of 17 years, without an adult to accompany him…a bold move for a young man. He arrived in New York City, like so many other immigrants. Before too long he had made his way to Blair,Nebraska, where he met and married Julia Doll on December 16, 1902. The couple would have ten children, the oldest of which was Andrew, my husband, Bob’s grandfather. The family would eventually settle in Forsyth, Montana, where there are still family members living to this day.

But what of the German half of the Schulenberg family. They had a longstanding heritage in Oldenburg, Germany, where the family owned a farm since 1705, when the first known Schulenberg owner, Johann Schulenberg shows up in records as the owner. The farm was rather large and still stands to this day. It has been well maintained, and is in fact, more beautiful today than it was when Johann owned it. I’m sure that has to do with all the modern equipment and products we have today to enhance the natural beauty of a home and its grounds. Nevertheless, the farm was a productive place in 1705 too.

Johann Schulenberg shows up in records as the owner. The farm was rather large and still stands to this day. It has been well maintained, and is in fact, more beautiful today than it was when Johann owned it. I’m sure that has to do with all the modern equipment and products we have today to enhance the natural beauty of a home and its grounds. Nevertheless, the farm was a productive place in 1705 too.

The furthest record of the family line that I have found to date is Vitter Schulenberg, who actually hailed from Schulenberg, Germany, where I expect the family originated, because as most of us know, before last names existed, people were known by the town they came from, such as Jesus of Nazareth. The Schulenberg family had been known in prior years as von der Schulenberg, which translates from Schulenberg, meaning the town of Schulenberg, Germany which is located in the district of Goslar in Lower Saxony, Germany, I don’t know if those people whose last name is spelled Schulenburg came from the same family or not, but I would expect that it is quite likely, because when people came to America, they were told to  Americanize their name, and there was no regulation as to how to do that, so some went one way and others went another way.

Americanize their name, and there was no regulation as to how to do that, so some went one way and others went another way.

I also found out that there was an older village of Schulenberg, which only appears in the fall, when the lake is at its lowest point. The lake (der Okertalsperre) or reservoir which was constructed in 1953, resulting in the flooding of the old village. That fascinated me. I found this picture of the ruins on Google Earth (taken by Harz Geist), and either there is not much left of the old village, or it was very small, which almost makes me wonder if it was originally a farm named Schulenberg, that grew into a village…but that is the subject of another story, for another day.