england

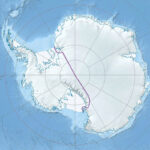

Over the centuries, there have been many exploratory expeditions all over the world. Some were privately financed, while others were financed by groups, governments, kings and as in the case of the 1955 to 1958 expedition to Antartica, the Commonwealth of England. The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) was an expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, by way of the South Pole. It was also the first expedition to reach the South Pole overland for 46 years. t was preceded only by Amundsen’s expedition and Scott’s expedition in 1911 and 1912. Antartica is a fierce, snow and ice covered, wilderness, which makes me wonder why anyone would want to be on an expedition there. Nevertheless, I suppose that it’s the adventure of it that attracts so many to attempts it.

Over the centuries, there have been many exploratory expeditions all over the world. Some were privately financed, while others were financed by groups, governments, kings and as in the case of the 1955 to 1958 expedition to Antartica, the Commonwealth of England. The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) was an expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, by way of the South Pole. It was also the first expedition to reach the South Pole overland for 46 years. t was preceded only by Amundsen’s expedition and Scott’s expedition in 1911 and 1912. Antartica is a fierce, snow and ice covered, wilderness, which makes me wonder why anyone would want to be on an expedition there. Nevertheless, I suppose that it’s the adventure of it that attracts so many to attempts it.

Traditionally, polar expeditions of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration were private ventures, and the CTAE was no exception, even though it was supported by the governments of the United Kingdom, New Zealand, United States, Australia and South Africa, as well as many corporate and individual donations, under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth II. The expedition was headed by British explorer Vivian Fuchs and included New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary. The group from New Zealand included scientists who were participating in International Geophysical Year research while the British team were separately based at Halley Bay.

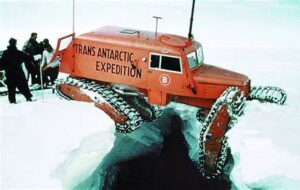

Fuchs took the Danish Polar vessel, Magga Dan and went for additional supplied, returning in December 1956. The southern summer of 1956–1957 was spent consolidating Shackleton Base and establishing the smaller South Ice Base, located about 300 miles inland to the south. The winter of 1957 found Fuchs at Shackleton Base. Then, finally, he set out on the transcontinental journey in November 1957. The twelve-man team traveled in six vehicles, three Sno-Cats, two Weasel tractors, and one specially adapted Muskeg tractor. While they traveled, the team was also tasked with carrying out scientific research including seismic soundings and  gravimetric readings. This was, after all a scientific expedition.

gravimetric readings. This was, after all a scientific expedition.

Hillary’s team began setting up Scott Base. This was going to be the final destination for Fuchs. It was located on the opposite side of the continent at McMurdo Sound on the Ross Sea. Using three converted Ferguson TE20 tractors and one Weasel, which had to be abandoned part-way, Hillary and his three men…Ron Balham, Peter Mulgrew, and Murray Ellis…were responsible for route-finding and laying a line of supply depots up the Skelton Glacier and across the Polar Plateau on towards the South Pole, for the use of Fuchs on the final leg of his journey. The remaining member of Hillary’s team carried out geological surveys around the Ross Sea and Victoria Land areas. The Hillary team was not originally supposed to travel as far as the South Pole, but when the supply depots were completed, Hillary saw the opportunity to beat the British and continued south, thereby reaching the Pole…where the US Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station had recently been established by air, on January 3, 1958. While he wasn’t supposed to go, Hillary’s party became the third team to reach the South Pole, preceded by Roald Amundsen in 1911 and Robert Falcon Scott in 1912. Hillary’s arrival also marked the first time that land vehicles had ever reached the Pole. It was a great historic moment.

Fuchs’ team finally reached the Pole from the opposite direction on January 19, 1958, where they met up with Hillary. From there, Fuchs continued overland, following the route that Hillary had forged to get to the South Pole. Then, Hillary flew back to Scott Base in a US plane. He would later rejoin Fuchs by plane for part of the remaining overland journey. The original overland party finally arrived at Scott Base on March 2, 1958, after having completed the historic crossing of 2,158 miles of previously unexplored snow and ice in 99 days. A few days later the expedition members left Antarctica on the on the New Zealand naval ship Endeavour, headed for New Zealand, with Captain Harry Kirkwood at the helm.

Although large quantities of supplies were hauled overland, many forms of resources were used in the expedition. Both parties were also equipped with light aircraft and made extensive use of air support for reconnaissance and supplies. US personnel working in Antartica at the time provided additional logistical help. Both parties also used dog teams for fieldwork trips and backup in case of failure of the mechanical transportation. The dogs were not taken all the way to the Pole. In December 1957 four men from the

expedition flew one of the planes…a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter—on an 11-hour, 1,430-mile, non-stop trans-polar flight across the Antarctic continent from Shackleton Base by way of the Pole to Scott Base, following roughly by air the same route as Fuchs’ overland party. For his accomplishments, Fuchs was knighted. The second overland crossing of the continent did not occur until 1981, during the Transglobe Expedition led by Ranulph Fiennes.

expedition flew one of the planes…a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter—on an 11-hour, 1,430-mile, non-stop trans-polar flight across the Antarctic continent from Shackleton Base by way of the Pole to Scott Base, following roughly by air the same route as Fuchs’ overland party. For his accomplishments, Fuchs was knighted. The second overland crossing of the continent did not occur until 1981, during the Transglobe Expedition led by Ranulph Fiennes.

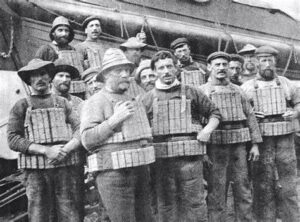

Like most safety equipment, people did not see the need for lifejackets until tragedy struck…at least not most people anyway. These days, we know that a personal flotation device (PFD…also referred to as a life jacket, life preserver, life belt, Mae West, life vest, life saver, cork jacket, buoyancy aid or flotation suit) is a flotation device in the form of a vest or suit that is worn by a user to prevent the wearer from drowning in a body of water. Most people know how important they are, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that most people use them. PFDs are known for keeping the wearer afloat with their head and mouth above the surface if they find themselves in the water due to a boating accident, or even a plane crash into water. People don’t have to know how to swim or tread water in order to stay afloat, and they can even be unconscious.

Like most safety equipment, people did not see the need for lifejackets until tragedy struck…at least not most people anyway. These days, we know that a personal flotation device (PFD…also referred to as a life jacket, life preserver, life belt, Mae West, life vest, life saver, cork jacket, buoyancy aid or flotation suit) is a flotation device in the form of a vest or suit that is worn by a user to prevent the wearer from drowning in a body of water. Most people know how important they are, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that most people use them. PFDs are known for keeping the wearer afloat with their head and mouth above the surface if they find themselves in the water due to a boating accident, or even a plane crash into water. People don’t have to know how to swim or tread water in order to stay afloat, and they can even be unconscious.

People have known for centuries that they needed such a device to ensure their safety when they are crossing deep streams and rivers. They created flotation devices out of inflated bladders, animal skins, or hollow sealed gourds to make for safer crossings. It is believed that Norwegian seamen created these first devices using blocks of wood or cork. Still not everyone paid attention to those who said they were important. The first known invention of a lifejacket came in 1854, when the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) Inspector,  Captain Ward, broke new ground in lifesaving with his new design of cork lifejacket. During the 19th century, RNLI volunteers had to manually row their boats when launching to rescue in stormy seas. When the first lifejacket design was created, it therefore needed to be flexible enough to move with the men as they paddled.

Captain Ward, broke new ground in lifesaving with his new design of cork lifejacket. During the 19th century, RNLI volunteers had to manually row their boats when launching to rescue in stormy seas. When the first lifejacket design was created, it therefore needed to be flexible enough to move with the men as they paddled.

RNLI lifeboatman, Henry Freeman, worked in Whitby, Yorkshire, England. Freeman was a big proponent of the latest safety item, the cork lifejacket. He tried to get the other lifeboatmen to wear cork lifejackets, but they did not see the need, nor did they think the new cork lifejackets were such a great invention. Nevertheless, Freeman was so sure that he never went on a rescue without one. The on February 9, 1961, off the shores of Whitby, a huge storm developed. By 8:30am, the lifeboat crew had launched their first rescue, successfully saving the crew of the John and Ann. A short time later, they were called out again to assist a schooner, Gamma, who had run aground. After their second successful rescue, the crew celebrated with a glass of grog at the station. As the storm grew worse, and after several more rescues, Harbormaster Mr Tose and Coxswain John Storr decided that if more vessels came in, they simply could not respond. The lifeboat would be of little use at a high tide in such a storm. A short time later, the Flora and the Merchant were spotted in trouble. The Flora successfully made it into the harbor, but the Merchant ran ashore.

Although the Whitby crew had agreed not to respond, they just couldn’t stand by and watch the Merchant sink. As they maneuvered towards the stricken collier, the lifeboat was hit by a powerful wave that caught the stern of the lifeboat, capsizing it and throwing the crew overboard. The crowd onshore watched in horror as the crew

struggled in the raging sea. in the end, all of the lifeboat crew were lost, except for Henry Freeman, who survived due to the cork lifejacket he had insisted on wearing. Freeman was on his first call out. I’m sure that there were those in the crew who laughed at Freeman for wearing the lifejacket, thinking he was just being ridiculous, but as they were losing their lives, I’m sure they regretted their decision not to wear one too.

struggled in the raging sea. in the end, all of the lifeboat crew were lost, except for Henry Freeman, who survived due to the cork lifejacket he had insisted on wearing. Freeman was on his first call out. I’m sure that there were those in the crew who laughed at Freeman for wearing the lifejacket, thinking he was just being ridiculous, but as they were losing their lives, I’m sure they regretted their decision not to wear one too.

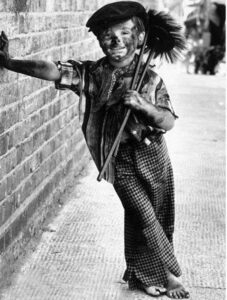

Perhaps one of the most questionable of all professions undertaken by children in the past was that of chimney sweeping. Not only were children exploited in this job, mostly because of their small stature, but since proper safety measures were not taken in those days, the children in those jobs had health problems for the rest of their lives, and very likely they died young. The use of children as chimney sweeps began in the late 1600s in England, after the Great Fire of London, which gutted the city. At that time, building codes changed, requiring chimneys to be much narrower than they were previously. The idea was to keep more of the sparks in than out.

Perhaps one of the most questionable of all professions undertaken by children in the past was that of chimney sweeping. Not only were children exploited in this job, mostly because of their small stature, but since proper safety measures were not taken in those days, the children in those jobs had health problems for the rest of their lives, and very likely they died young. The use of children as chimney sweeps began in the late 1600s in England, after the Great Fire of London, which gutted the city. At that time, building codes changed, requiring chimneys to be much narrower than they were previously. The idea was to keep more of the sparks in than out.

The new design brought with it a bigger problem…keeping the chimneys free of obstruction, which became more of a challenge and a priority. Amazingly, instead of someone inventing a tool for this purpose, children were employed as human chimney sweeps. Their small stature allowed them to go inside the chimneys and manually sweep away the soot. Thus practice went on for over 200 years, in spite of the deplorable conditions the children lived in, the horrible health effects they suffered, and the many injuries and fatalities resulting from related work hazards.

One former chimney sweep, James Seaward was interviewed in December 1909, by the Toronto Saturday Night, a Canadian publication. Seaward was living in Wokingham, where he had just been named alderman of the town’s Borough Council. Seaward was one of the fortunate few that were still alive after working as a chimney sweep for 58 years. He started when he was just six. Seaward tells how he “was only six years old when I went up my first chimney. I was an orphan and I fell into the hands of a chimney sweep, and a cruel master he was. I have known what it was to have straw lighted under me and pins stuck into the soles of my feet to force me up a chimney; and I have known, too, what it was to come down covered with blood and soot after climbing with my knees and elbows. No one knows the terrible cruelty inflicted on boys in those days.

They used to be steeped in strong brine to harden their flesh. In my own case soda was used. Sometimes I used to have to stay up a difficult chimney five or six hours at a stretch.”

They used to be steeped in strong brine to harden their flesh. In my own case soda was used. Sometimes I used to have to stay up a difficult chimney five or six hours at a stretch.”

Somehow, Seaward managed to survive, and to actually prosper, even is such deplorable conditions. Thankfully, such cruelty was outlawed during the nineteenth century, with laws introduced regarding child labor. Those laws didn’t address chimney sweeps specifically, but rather child labor in general. The things that were allowed in the past concerning child labor were just awful, and orphans were specifically targeted, because they had little protections over their lives. They were often “adopted” out, but their “new parents” sometimes just wanted slave labor.

When I first heard about the bizarre phenomenon found under the home of Benjamin Franklin, I thought of a few possibilities. The remains, found in 1998, consisted of 1,200 bones are believed to be from more than 15 human bodies found in the basement of Ben Franklin’s house. Six of the bodies were children. My first thought was, “Please tell me that this is some Indian burial site, or that there is some logical explanation as to why there would be bodies buried in this hero Founding Father’s home.” I have always liked Ben Franklin. I found his “antics” to be so interesting. To say the least, he was a bit strange in his experimentations, and that was enough to make me wonder (and hope it wasn’t so) if Ben Franklin could possibly have some horrid alter ego. He wouldn’t be the first scientist to go off the deep end to experiment on human bodies, but then again, there certainly are people today that have chosen to donate their bodies to science, so why couldn’t that be the case back then. I prayed that was the case.

When I first heard about the bizarre phenomenon found under the home of Benjamin Franklin, I thought of a few possibilities. The remains, found in 1998, consisted of 1,200 bones are believed to be from more than 15 human bodies found in the basement of Ben Franklin’s house. Six of the bodies were children. My first thought was, “Please tell me that this is some Indian burial site, or that there is some logical explanation as to why there would be bodies buried in this hero Founding Father’s home.” I have always liked Ben Franklin. I found his “antics” to be so interesting. To say the least, he was a bit strange in his experimentations, and that was enough to make me wonder (and hope it wasn’t so) if Ben Franklin could possibly have some horrid alter ego. He wouldn’t be the first scientist to go off the deep end to experiment on human bodies, but then again, there certainly are people today that have chosen to donate their bodies to science, so why couldn’t that be the case back then. I prayed that was the case.

At this point, many people would immediately assume that Ben Franklin was some kind of closet killer, who tortured and murdered his victims. It would be thought that the world had been so naive, that we lived in the dark for years, but before you go crafting a murder mystery about him, please be aware that it was revealed that the bodies were used in the study of human anatomy. So, it actually was bodies donated for scientific  research. I certainly didn’t know that they did that sort of thing back then, but it seems that they did.

research. I certainly didn’t know that they did that sort of thing back then, but it seems that they did.

The house, located in London, England was undergoing some conservation work in 1998, when the bones were discovered. Some of the bodies were dismembered, or had trepanned skulls, which is skulls with holes drilled through them. Ben Franklin had lived home in London for nearly twenty years leading up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was more than 200 years later, when the conservation work uncovered the 15 bodies in the basement, buried in a secret, windowless room beneath the garden. While on could imagine horrible things, “The most plausible explanation is not mass murder, but an anatomy school run by Benjamin Franklin’s young friend and protege, William Hewson.” So, it would seem that Ben Franklin either loaned the home to Hewson (a surgeon), stored the bodies for Hewson, or allowed Hewson to do his scientific experiments in the room in the Franklin house. Whatever the case may be, it is apparently well enough documented that the authorities were satisfied that Ben Franklin wasn’t personally involved.

One such speculation was that “Anatomy was still in its infancy, but the day’s social and ethical mores frowned upon it. … A steady supply of human bodies was hard to come by legally, so Hewson, Hunter, and the field’s other pioneers had to turn to grave robbing—either paying professional ‘resurrection men’ to procure cadavers  or digging them up themselves—to get their hands on specimens. Researchers think that 36 Craven was an irresistible spot for Hewson to establish his own anatomy lab. The tenant was a trusted friend, the landlady was his mother-in-law, and he was flanked by convenient sources for corpses. Bodies could be smuggled from graveyards and delivered to the wharf at one end of the street or snatched from the gallows at the other end. When he was done with them, Hewson simply buried whatever was left of the bodies in the basement, rather than sneak them out for disposal elsewhere and risk getting caught and prosecuted for dissection and grave robbing.” Some people speculate that Ben Franklin knew about the goings on, but was not personally involved, still, they thought he might have gone to the lab a few times to check out the proceedings. I hate to think that he knew anything about it, and I would prefer to think that the study of anatomy was done in his absence, but I suppose that our modern-day anatomy studies and autopsies were probably pioneered in a basement somewhere.

or digging them up themselves—to get their hands on specimens. Researchers think that 36 Craven was an irresistible spot for Hewson to establish his own anatomy lab. The tenant was a trusted friend, the landlady was his mother-in-law, and he was flanked by convenient sources for corpses. Bodies could be smuggled from graveyards and delivered to the wharf at one end of the street or snatched from the gallows at the other end. When he was done with them, Hewson simply buried whatever was left of the bodies in the basement, rather than sneak them out for disposal elsewhere and risk getting caught and prosecuted for dissection and grave robbing.” Some people speculate that Ben Franklin knew about the goings on, but was not personally involved, still, they thought he might have gone to the lab a few times to check out the proceedings. I hate to think that he knew anything about it, and I would prefer to think that the study of anatomy was done in his absence, but I suppose that our modern-day anatomy studies and autopsies were probably pioneered in a basement somewhere.

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

The design called for 60,000 panes of glass to adorn the building. On average, a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week. These were manufactured by the Chance Brothers. The building was finished in 39 weeks. The Crystal Palace boasted the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building. Visitors were shocked and astonished by all the clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights. The interior of the building had full grown trees!! The full-size elm trees that had been growing in the park were simply enclosed within the central exhibition hall near the 27-foot-tall Crystal Fountain. While very nice looking, the trees caused a problem with sparrows becoming a nuisance, and of course, shooting was out of the question inside a glass building. When Queen Victoria mentioned this problem to the Duke of Wellington, he offered the solution, “Sparrowhawks, Ma’am.” Now to me, that is incredulous, because you would simply be replacing on kind of bird with another, and then there was the added problem of bird violence. I don’t think the visitors would be very thrilled about the fighting birds or dropping bodies.

Incredibly, the Palace was relocated after the Great Exhibition, to an open area of South London known as Penge Place which had been excised from Penge Common. The building was rebuilt at the top of Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, which is an affluent suburb. The Crystal Palace stood in that location from June 1854 until a fire destroyed it in November 1936. After the fire, the suburb was renamed Crystal Palace after the landmark. In addition, a park was placed in the area and named Crystal Palace Park. It surrounds the site, and is home of the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, which was previously a football stadium that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914. Crystal Palace Football Club were founded at the site and played at the Cup Final venue in their early years. The site still contains Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s Crystal Palace Dinosaurs which date back to 1854.

In the 1920s, a board of trustees was set up under the guidance of manager Sir Henry Buckland. Buckland was a fair man with a great love for the Crystal Palace, decided to restore the building. Following the restoration, the visitors returned, and the Crystal Palace started to become profitable again. Buckland and his staff also worked on improving the fountains and gardens, including the Thursday evening displays of fireworks by Brocks. Then, on the evening of November 30, 1936, Buckland was walking his dog near the Palace with his daughter Crystal. Buckland had named her after the building. Always looking at the building he loved, they noticed a red glow coming from inside. Buckland went in to investigate and found two of his employees fighting a small office fire that had started after an explosion in the women’s cloakroom. Buckland could see that this was a serious fire, so they called the Penge fire brigade. It was too late. Even with the 89 fire engines and over 400 firemen, the fire was too big and too out of control to be able to extinguish it.

The infamous Crystal Palace was destroyed. The fire was so big that its glow could be seen across eight counties. With high winds that night, the fire spread quickly, and in part because of the dry old timber flooring, and the huge quantity of flammable materials in the building it burned to the ground. Buckland said, “In a few hours we have seen the end of the Crystal Palace. Yet, it will live in the memories not only of Englishmen, but the whole world.” The fire brought one-hundred thousand spectators to Sydenham Hill that night. One of the

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

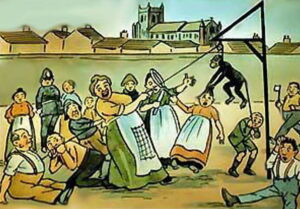

A story is told in Hartlepool, England about an incident during the Napoleonic Wars, of an incident involving a monkey, who came into the custody of the British Army when the ship he was on was wrecked in a storm of the coast of Hartlepool. The sole survivor from the sip was said to be a monkey, who the captain owned, and dressed in the uniform of the ship. That being French, his little uniform was that of the French Army as a form of amusement for the crew. The monkey managed to make it to the shore and was found by a group of locals who apparently also were amused. They decided to hold an impromptu trial, because the monkey was, after all the enemy. Because the monkey was unable to answer their questions, and because they had seen neither a monkey nor a Frenchman before, they concluded that the monkey must be a French spy. With that, they found the monkey guilty and sentenced him to death by hanging, right there on the beach.

A story is told in Hartlepool, England about an incident during the Napoleonic Wars, of an incident involving a monkey, who came into the custody of the British Army when the ship he was on was wrecked in a storm of the coast of Hartlepool. The sole survivor from the sip was said to be a monkey, who the captain owned, and dressed in the uniform of the ship. That being French, his little uniform was that of the French Army as a form of amusement for the crew. The monkey managed to make it to the shore and was found by a group of locals who apparently also were amused. They decided to hold an impromptu trial, because the monkey was, after all the enemy. Because the monkey was unable to answer their questions, and because they had seen neither a monkey nor a Frenchman before, they concluded that the monkey must be a French spy. With that, they found the monkey guilty and sentenced him to death by hanging, right there on the beach.

Apparently, any enemy soldier was to be dealt with in this manner and a trial wasn’t even really necessary. As the story goes, they proceeded with the “hanging” and found it a seriously difficult task, because the monkey kept climbing up the rope to safety. The whole situation, and the local townspeople because the laughingstock of the area, due to their inability to carry out a simple hanging. Everyone in the area got such a kick out of the whole situation, that they made up a song, and even changed the mascot of the local rugby teams to one or the other version of “The Monkey Hangers.” In fact, it was the decision of the local football club, Hartlepool United FC, who capitalized on their “Monkey Hangers” nickname by creating a mascot called “H’Angus the Monkey” in 1999. Two of the town’s six rugby union clubs also use variations of the hanging monkey. Hartlepool Rovers crest being a beret wearing monkey hanging from a gibbet, while Hartlepool RFC neckties sport a rugby ball kicking monkey suspended from a rope.

A statue of the monkey has been erected on the Headland and another at Hartlepool Marina (formerly in West Hartlepool). The statues serve to collect coins for a local hospice. Although some Hartlepool residents find the term “monkey hanger” insulting, a large number of residents have embraced the term and celebrate it as an important and unique characteristic of the town. Those offended thought it made them look stupid and incapable of sensible thought. I can understand both trains of thought, because no one wants to look stupid. Still, maybe they should have just embraced it as the joke it was. It doesn’t look like it is going away anyway.

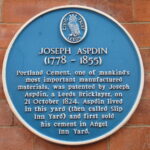

People in our modern-day world truly take some of history’s inventions for granted. Things that have been around for a long time, are especially susceptible. Around 3000 BC, the Egyptians used early concrete forms as mortar in their construction work. The Great Pyramids at Giza were built from an early form of concrete, and they are still standing today. It seems strange to think of concrete existing way back then, but it actually did. It might not have been in exactly the same form as the concrete of today. In fact, the Bible tells of using clay and straw to make bricks and mortar. It seems rather archaic to us these days, and but then it seems to have lasted a whole lot longer than some of the concrete of today, so maybe some of it was better.

People in our modern-day world truly take some of history’s inventions for granted. Things that have been around for a long time, are especially susceptible. Around 3000 BC, the Egyptians used early concrete forms as mortar in their construction work. The Great Pyramids at Giza were built from an early form of concrete, and they are still standing today. It seems strange to think of concrete existing way back then, but it actually did. It might not have been in exactly the same form as the concrete of today. In fact, the Bible tells of using clay and straw to make bricks and mortar. It seems rather archaic to us these days, and but then it seems to have lasted a whole lot longer than some of the concrete of today, so maybe some of it was better.

Portland cement was invented by Joseph Aspdin of England in 1824. The first concrete  paved street in the United States was laid in Bellefontaine, Ohio in 1891. The street was paved by George W Bartholomew, who owned the Buckeye Portland Cement Company and convinced city officials to let him pave an eight-foot-wide strip of Main Street with a mixture of sand, stone, and cement. Two years later, city officials agreed to let Bartholomew pave an entire block of Court Avenue between Main Street and Opera Street, which today remains the oldest concrete street in America, and it still exists, unlike some of the products currently used for streets today.

paved street in the United States was laid in Bellefontaine, Ohio in 1891. The street was paved by George W Bartholomew, who owned the Buckeye Portland Cement Company and convinced city officials to let him pave an eight-foot-wide strip of Main Street with a mixture of sand, stone, and cement. Two years later, city officials agreed to let Bartholomew pave an entire block of Court Avenue between Main Street and Opera Street, which today remains the oldest concrete street in America, and it still exists, unlike some of the products currently used for streets today.

Steel-reinforced concrete was developed by the end of the 19th century. August Perret designed and built an apartment building in Paris using steel-reinforced concrete in 1902. The building was widely admired, and with that building came a new popularity for concrete. In fact, the building influenced further development of reinforced concrete. Eugène Freyssinet really pioneered reinforced-concrete construction by building two colossal parabolic-arched airship hangars at Orly Airport in Paris in 1921.

Concrete has undergone several changes since 1921. During the 21st century, concrete manufacturers have  sstarted changing many of their product formulas in ways that increase early strength and lessen later age trength. This threw me a little bit, but the primary reason for this shift is said to be practical…”On a construction site, you can remove the forms from new concrete much faster if it has high early strength 1. Additionally, according to AZoBuild.com, concrete has gone through numerous changes over the last few decades despite its appearance looking almost the same. These changes include the development of environmentally friendly concrete products.” I’m not sure these changes are all that good, because they seem to cause more cracking and an earlier breakdown of the concrete. I’m not a contractor, but that doesn’t seem like a good thing to me.

sstarted changing many of their product formulas in ways that increase early strength and lessen later age trength. This threw me a little bit, but the primary reason for this shift is said to be practical…”On a construction site, you can remove the forms from new concrete much faster if it has high early strength 1. Additionally, according to AZoBuild.com, concrete has gone through numerous changes over the last few decades despite its appearance looking almost the same. These changes include the development of environmentally friendly concrete products.” I’m not sure these changes are all that good, because they seem to cause more cracking and an earlier breakdown of the concrete. I’m not a contractor, but that doesn’t seem like a good thing to me.

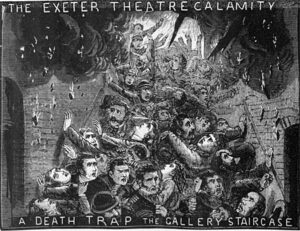

In American schools, and maybe in schools all over the world, children are used to the occasional fire drill, because it is a practice is designed to allow people to escape a fire, instead of losing their lives in a panic. Of course, this practice is fairly new, and came about after a number of fire disasters. One such disaster was the September 5, 1887, Exeter Theatre Royal fire in Exeter, England.

In American schools, and maybe in schools all over the world, children are used to the occasional fire drill, because it is a practice is designed to allow people to escape a fire, instead of losing their lives in a panic. Of course, this practice is fairly new, and came about after a number of fire disasters. One such disaster was the September 5, 1887, Exeter Theatre Royal fire in Exeter, England.

The fire broke out in the backstage area of the theatre during the production of “The Romany Rye” by George Robert Sims and produced by Wilson Barrett. When the fire was known, a panic ensued throughout the theatre. Whenever there is panic, someone is going to get hurt, or worse. In this case, 186 people died from a combination of the direct effects of smoke and flame, crushing and trampling, and trauma injuries from falling or jumping from the roof and balconies. It is such a sad situation, because if they had not panicked, it is likely that all or most of those would have survived. Of course, panic was not the only reason for the deaths, so we will never truly know if this could have been prevented. The Exeter Theatre Royal death toll makes it the worst theatre disaster, the worst single-building fire, and the third worst fire-related disaster in the history of the United Kingdom. Most of those who lost their lives were in the gallery of the theatre, which had only a single exit with several design flaws. The exit quickly became clogged with people trying to escape.

This was not the first time the Theatre Royal had been destroyed. The first Exeter Theatre Royal had been gutted by fire in 1885, and the new theatre was opened, on a new site, in 1886 to the design of well-known theatre architect CJ Phipps. The new theatre was leased exclusively to Sidney Herberte-Basing. The new  building was constructed from stone and red brick on the outside, but the inside was largely constructed of wood. Following the 1885 fire, the licensing authority of Exeter City Council ordered that the new theatre be constructed “in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Metropolitan Board of Works,” which was a statutory requirement in London under The Metropolitan Building Act 1855 (with theatre particulars added in the 1878 amendment), but not required in the regions. In his letter accompanying the plans to the Corporation Surveyor of Exeter City Council, Phipps directly states that the building met all the rules and requirements laid out, ans added that he had extensive experience in these types of construction. The letter stated, “…the theatre is designed in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Board of Works under the Act of 1878 and of the Lord Chamberlain – and having constructed some 40 theatres, I bring a somewhat large experience to bear on this subject.” – C.J. Phipps, Letter of 11 July 1885 from Phipps to the Corporation Surveyor of the City of Exeter.

building was constructed from stone and red brick on the outside, but the inside was largely constructed of wood. Following the 1885 fire, the licensing authority of Exeter City Council ordered that the new theatre be constructed “in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Metropolitan Board of Works,” which was a statutory requirement in London under The Metropolitan Building Act 1855 (with theatre particulars added in the 1878 amendment), but not required in the regions. In his letter accompanying the plans to the Corporation Surveyor of Exeter City Council, Phipps directly states that the building met all the rules and requirements laid out, ans added that he had extensive experience in these types of construction. The letter stated, “…the theatre is designed in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Board of Works under the Act of 1878 and of the Lord Chamberlain – and having constructed some 40 theatres, I bring a somewhat large experience to bear on this subject.” – C.J. Phipps, Letter of 11 July 1885 from Phipps to the Corporation Surveyor of the City of Exeter.

Nevertheless, during the licensing inspection, several deficiencies were noted and ordered to be corrected, including “installing an additional exit for the audience from the boxes, stalls, and pit, widening the exits to at  least 6 feet, changing some single leaf exit doors to double doors, and supplying 80 feet of hose for each hydrant (of which there were only two – one in the foyer and one in the “prompts” in front of the stage), rather than 40 feet which had been provided.” Unfortunately, there was no inspection of the stage, the mezzanine floor, or the fly galleries above the stage. There was only one exit with four right angled turns in it, from this area, and while two exits were called for, the idea was passed over because Phipps asserted “that a second exit was provided by climbing the railing at the front of the gallery and dropping to the second circle below.” That was, of course a crazy notion, that cost lives in the end. Apparently, this plan was accepted without further argument. In addition, there was to be an iron safety curtain, which was not fitted at the time of the fire, and a fire hydrant in the stage wings was on the plans of the theatre but never installed, despite Phipps being advised that the two hydrants installed were insufficient. In the end, the panic, along with the mishandled inspections and the improper plan design cost 186 people their lives.

least 6 feet, changing some single leaf exit doors to double doors, and supplying 80 feet of hose for each hydrant (of which there were only two – one in the foyer and one in the “prompts” in front of the stage), rather than 40 feet which had been provided.” Unfortunately, there was no inspection of the stage, the mezzanine floor, or the fly galleries above the stage. There was only one exit with four right angled turns in it, from this area, and while two exits were called for, the idea was passed over because Phipps asserted “that a second exit was provided by climbing the railing at the front of the gallery and dropping to the second circle below.” That was, of course a crazy notion, that cost lives in the end. Apparently, this plan was accepted without further argument. In addition, there was to be an iron safety curtain, which was not fitted at the time of the fire, and a fire hydrant in the stage wings was on the plans of the theatre but never installed, despite Phipps being advised that the two hydrants installed were insufficient. In the end, the panic, along with the mishandled inspections and the improper plan design cost 186 people their lives.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

The sinking, brought with it a claim from the Germans that the submarine’s crew had  followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave

followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave  those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

The sinking of RMS Falaba, and Thrasher’s subsequent death, was mentioned again in a memorandum sent by the US government, which was drafted by President Woodrow Wilson himself and addressed to the German government after the German submarine attack on the British passenger ship Lusitania on May 7, 1915, in which 1,201 people were drowned, including 128 Americans. President Wilson’s note was clearly a warning, calling for the US and Germany to come to a full and complete understanding as to the grave situation which had resulted from the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. In response to the warning, Germany abandoned the policy shortly thereafter. However, the policy abandonment was reversed in early 1917, and that was the final straw that put the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917.

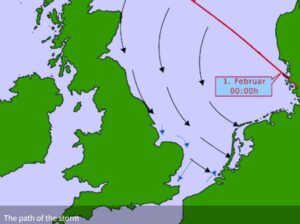

The early warning systems we have in place these days could have easily saved many of the lives of the 2551 people who lost their lives on January 31, 1953, during the North Sea Flood. The flood caused catastrophic damage and loss of life in Scotland, England, Belgium and The Netherlands. It became one of the worst peacetime disasters of the 20th century. In the course of the flood, 307 people died in England, 19 died in Scotland, 28 died in Belgium, 1,836 died in the Netherlands, and an additional 361 people died at sea.

The early warning systems we have in place these days could have easily saved many of the lives of the 2551 people who lost their lives on January 31, 1953, during the North Sea Flood. The flood caused catastrophic damage and loss of life in Scotland, England, Belgium and The Netherlands. It became one of the worst peacetime disasters of the 20th century. In the course of the flood, 307 people died in England, 19 died in Scotland, 28 died in Belgium, 1,836 died in the Netherlands, and an additional 361 people died at sea.

The North Sea Flood of 1953 was an unusual storm, that was caused by a number of contributing elements, that combined together to make it more deadly and devastating than the average storm or even the average flood. The annual spring tides, a deep pressure system…something that in itself can cause the sea to rise, combined with severe gale force winds…recorded at 126 miles per hour at Costa Hill in Scotland and the result was the North Sea Flood of 1953. All of these elements funneled those high tides southward toward the narrow, and shallow…just 571 feet deep, English Channel, causing the swell to rise even further. The storm surge was recorded at 18.4 feet at its peak.

The tide came in slowly at first, and nobody was alarmed. The official weather forecast was a slight drizzle and strong winds but nothing regarding waves and tidal flow. Life went on as usual, the ships set sail and people went to work or to play. Yes, life went on as usual…until it didn’t. What began as a calm evening was quickly changed into a nightmare. The tide became unpredictable and surged over the sea walls at different points during the evening, taking many by surprise and leaving no time to warn others. One survivor in Norfolk said, that it took less than 15 minutes from the water first tricking into his home, to reaching almost 5 feet. Those living closest to the sea reported that a wall of water came over almost immediately with many homes collapsing instantaneously with the force of the water rushing in. There was no warning system available to them. No one knew how bad this storm was…until it was way too late. The survivors became the first responders, because there was no one else. They couldn’t communicate the emergency need, or at the very least, communication was delayed. Outside of the affected areas, the first that many knew of what had happened was many hours after the majority of people had been killed.

Following the devastation, Questions began to emerge regarding the lack of warning given to the people, and because of that, the number of deaths. Priority was given to repairing the sea walls and rebuilding the homes of the people. In the aftermath, however it was going to be the long-term flood defenses that would change the future outcomes. The Thames Barrier was designed and built following the lessons from the 1953 flood.

Warning sirens were put in place at the most at risk areas and are still in use today. The Dutch government quickly formed the Delta commission to study the floods and eventually commissioned the ‘Delta Works’ to enable the closing of estuaries to prevent upstream flooding and included dams, sluices, locks, dikes, levees, and barriers. Taxes were implemented and readily accepted with a national mind-set that this must never happen again. Even today, commemorations still happen on every anniversary for the dead.

Warning sirens were put in place at the most at risk areas and are still in use today. The Dutch government quickly formed the Delta commission to study the floods and eventually commissioned the ‘Delta Works’ to enable the closing of estuaries to prevent upstream flooding and included dams, sluices, locks, dikes, levees, and barriers. Taxes were implemented and readily accepted with a national mind-set that this must never happen again. Even today, commemorations still happen on every anniversary for the dead.