World War I

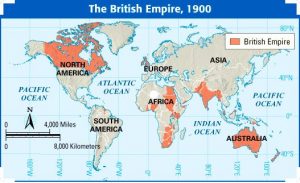

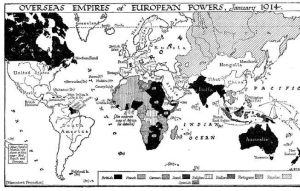

World wars are a complicated matter. There are multiple enemies, multiple allies, and the lines are not necessarily very clear. The one thing that always seems to be a constant, however, is territory. Imperialism…when a country takes over new lands or countries and makes them subject to their rule, played a big roll in World War I, as did industrialism. By 1900, any territorial gain by one power meant the loss of territory by another, and for Britain, the strongest of all the empires, that was a problem. Britain’s colonial territory was over 100 times the size of its own territory at home, thus giving rise to the phrase “the sun never sets on the British empire.” At this same time, France had control of large areas of Africa. With the rise of industrialism countries needed new markets. The amount of lands owned by Britain and France increased the rivalry with Germany who had entered the scramble to acquire colonies late and only had small areas of Africa.

World wars are a complicated matter. There are multiple enemies, multiple allies, and the lines are not necessarily very clear. The one thing that always seems to be a constant, however, is territory. Imperialism…when a country takes over new lands or countries and makes them subject to their rule, played a big roll in World War I, as did industrialism. By 1900, any territorial gain by one power meant the loss of territory by another, and for Britain, the strongest of all the empires, that was a problem. Britain’s colonial territory was over 100 times the size of its own territory at home, thus giving rise to the phrase “the sun never sets on the British empire.” At this same time, France had control of large areas of Africa. With the rise of industrialism countries needed new markets. The amount of lands owned by Britain and France increased the rivalry with Germany who had entered the scramble to acquire colonies late and only had small areas of Africa.

During this time Germany became concerned that Russia might try to take over their nation, so they signed a  treaty with Austria-Hungary to protect each other from Russia. The Dual Alliance was created by treaty on October 7, 1879 as part of Bismarck’s system of alliances to prevent or limit war. The two powers promised each other support in case of attack by Russia. Also, each state promised benevolent neutrality to the other if one of them was attacked by another European power, most likely France. Germany’s Otto von Bismarck saw the alliance as a way to prevent the isolation of Germany and to preserve peace, as Russia would not wage war against both empires. Then in 1881, Austria-Hungary made an alliance with Serbia to stop Russia from gaining control of Serbia. Before long alliances were popping up everywhere. Germany and Austria-Hungary made an alliance with Italy in 1882 that was dubbed The Triple Alliance to stop Italy from taking sides with Russia. Then in 1894, Russia formed an alliance with France called the Franco-Russian Alliance, to protect Russia against Germany and Austria-Hungary.

treaty with Austria-Hungary to protect each other from Russia. The Dual Alliance was created by treaty on October 7, 1879 as part of Bismarck’s system of alliances to prevent or limit war. The two powers promised each other support in case of attack by Russia. Also, each state promised benevolent neutrality to the other if one of them was attacked by another European power, most likely France. Germany’s Otto von Bismarck saw the alliance as a way to prevent the isolation of Germany and to preserve peace, as Russia would not wage war against both empires. Then in 1881, Austria-Hungary made an alliance with Serbia to stop Russia from gaining control of Serbia. Before long alliances were popping up everywhere. Germany and Austria-Hungary made an alliance with Italy in 1882 that was dubbed The Triple Alliance to stop Italy from taking sides with Russia. Then in 1894, Russia formed an alliance with France called the Franco-Russian Alliance, to protect Russia against Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Now at this point, I’m sure you feel as confused about all this as I did. To me, it seems like it would be very difficult to know who the enemy really was, and even if you knew, it was subject to change, depending on who they formed an alliance with. That is also why I was wondering why on June 16, 1918, the Battle of the Piave River was raging on the Italian front. Russia had bowed out of the war effort in early 1918, and Germany began  to pressure its ally, Austria-Hungary, to devote more resources to combating Italy. Wait…I thought Italy was their ally…apparently not so much. Specifically, the Germans wanted a major new offensive along the Piave River, located just a few kilometers from such important Italian urban centers as Venice, Padua and Verona. In addition to striking on the heels of Russia’s withdrawal, the offensive was intended as a follow-up to the spectacular success of the German-aided operations at Caporetto in the autumn of 1917. Wars really seem to be quite senseless, but when Imperialistic nations try to expand their territories, I guess, alliances can be made and broken quite easily.

to pressure its ally, Austria-Hungary, to devote more resources to combating Italy. Wait…I thought Italy was their ally…apparently not so much. Specifically, the Germans wanted a major new offensive along the Piave River, located just a few kilometers from such important Italian urban centers as Venice, Padua and Verona. In addition to striking on the heels of Russia’s withdrawal, the offensive was intended as a follow-up to the spectacular success of the German-aided operations at Caporetto in the autumn of 1917. Wars really seem to be quite senseless, but when Imperialistic nations try to expand their territories, I guess, alliances can be made and broken quite easily.

When the United States entered World War I, they sent men into France to join Allied forces there. Their arrival was a great relief to the exhausted Allied soldiers. Before long the American soldiers in France became known as Doughboys. This was not an unknown term, since it had been used For centuries to describe such soldiers as Horatio Nelson’s sailors and Wellington’s soldiers in Spain, for instance. Both of these groups were familiar with fried flour dumplings called doughboys, the predecessor of the modern doughnut that both we and the Doughboys of World War I came to love. The American Doughboys were the men America sent to France in the Great War, who beat Kaiser Bill and fought to make the world safe for Democracy.

When the United States entered World War I, they sent men into France to join Allied forces there. Their arrival was a great relief to the exhausted Allied soldiers. Before long the American soldiers in France became known as Doughboys. This was not an unknown term, since it had been used For centuries to describe such soldiers as Horatio Nelson’s sailors and Wellington’s soldiers in Spain, for instance. Both of these groups were familiar with fried flour dumplings called doughboys, the predecessor of the modern doughnut that both we and the Doughboys of World War I came to love. The American Doughboys were the men America sent to France in the Great War, who beat Kaiser Bill and fought to make the world safe for Democracy.

It is thought, however, that the Doughboys of World War I might have acquired the name in a slightly different way. In fact, there are a variety of theories about the origins of the nickname. One explanation is that the term dates back to the Mexican War of 1846 to 1848, when American infantrymen made long treks over dusty terrain, giving them the appearance of being covered in flour, or dough. As a variation of this account goes, the men were coated in the dust of adobe soil and as a result were called “adobes,” which morphed into “dobies” and, eventually into “doughboys.” Among other theories, according to “War Slang” by Paul Dickson, American journalist and lexicographer H.L. Mencken claimed the nickname could be traced to Continental Army soldiers who kept the piping on their uniforms white through the application of clay. When the troops got rained on the clay on their uniforms turned into “doughy blobs,” supposedly leading to the doughboy moniker.

Whatever the case may be, doughboy was just one of the nicknames given to those who fought in the Great War. For example, “poilu” meaning “hairy one” was a term for a French soldier, as a number of them had beards or mustaches, while a popular slang term for a British soldier was “Tommy,” an abbreviation of Tommy Atkins, a generic name similar to John Doe used in the Unites States on government forms. America’s last

World War I doughboy, Frank Buckles, died in 2011 in West Virginia at age 110. Buckles enlisted in the Army at age 16 in August 1917, four months after the United States entered the conflict, and drove military vehicles in France. One of 4.7 million Americans who served in the war, Buckles was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. It’s strange to think that my grandfather, George Byer was one of the men called doughboys, but then he was stationed in France at that time in history, so I guess that Grandpa was a doughboy.

World War I doughboy, Frank Buckles, died in 2011 in West Virginia at age 110. Buckles enlisted in the Army at age 16 in August 1917, four months after the United States entered the conflict, and drove military vehicles in France. One of 4.7 million Americans who served in the war, Buckles was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. It’s strange to think that my grandfather, George Byer was one of the men called doughboys, but then he was stationed in France at that time in history, so I guess that Grandpa was a doughboy.

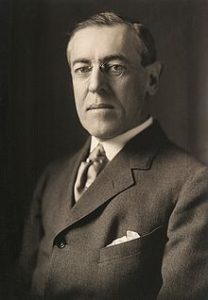

While Germany was willing to go to war, they had, nevertheless, a healthy fear of the United States. During World War I, Germany introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. It was early 1915, and Germany decided that the area around the British Isles was a war zone, and all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. That action set in motion a series of attacks on merchant ships, that finally led to the sinking of the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. It was at this point that President Woodrow Wilson decided that it was time to pressure the German government to curb their naval actions. Because the German government didn’t want to antagonize the United States, they agreed to put restrictions on the submarine policy going forward, which angered many of their naval leaders, including the naval commander in chief, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who showed his frustration by resigning in March 1916.

While Germany was willing to go to war, they had, nevertheless, a healthy fear of the United States. During World War I, Germany introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. It was early 1915, and Germany decided that the area around the British Isles was a war zone, and all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. That action set in motion a series of attacks on merchant ships, that finally led to the sinking of the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. It was at this point that President Woodrow Wilson decided that it was time to pressure the German government to curb their naval actions. Because the German government didn’t want to antagonize the United States, they agreed to put restrictions on the submarine policy going forward, which angered many of their naval leaders, including the naval commander in chief, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who showed his frustration by resigning in March 1916.

On March 24, 1916, soon after Tirpitz’s resignation, a German U-boat submarine attacked the French passenger steamer Sussex, in the English Channel, thinking it was a British ship equipped to lay explosive mines. It was apparently an honest mistake, and the ship did not sink. Still, 50 people were killed and many  more injured, including several Americans. On April 19, in an address to the United States Congress, President Wilson took a firm stance, stating that unless the Imperial German Government agreed to immediately abandon its present methods of warfare against passenger and freight carrying vessels the United States would have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the Government of the German Empire altogether.

more injured, including several Americans. On April 19, in an address to the United States Congress, President Wilson took a firm stance, stating that unless the Imperial German Government agreed to immediately abandon its present methods of warfare against passenger and freight carrying vessels the United States would have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the Government of the German Empire altogether.

After Wilson’s speech, the US ambassador to Germany, James W. Gerard, spoke directly to Kaiser Wilhelm on May 1 at the German army headquarters at Charleville in eastern France. After Gerard protested the continued German submarine attacks on merchant ships, the Kaiser in turn denounced the American government’s compliance with the Allied naval blockade of Germany, in place since late 1914. Nevertheless, Germany could not risk American entry into the war against them, so when Gerard urged the Kaiser to provide assurances of a change in the submarine policy, the Kaiser agreed.

On May 6, the German government signed the so-called Sussex Pledge, promising to stop the indiscriminate sinking of non-military ships. According to the pledge, merchant ships would be searched, and sunk only if they  were found to be carrying contraband materials. Furthermore, no ship would be sunk before safe passage had been provided for the ship’s crew and its passengers. Gerard was skeptical of the intentions of the Germans, and wrote in a letter to the United States State Department that “German leaders, forced by public opinion, and by the von Tirpitz and Conservative parties would take up ruthless submarine warfare again, possibly in the autumn, but at any rate about February or March, 1917.” Gerard was right, and on February 1, 1917, Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, Wilson announced a break in diplomatic relations with the German government, and on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I on the side of the Allies.

were found to be carrying contraband materials. Furthermore, no ship would be sunk before safe passage had been provided for the ship’s crew and its passengers. Gerard was skeptical of the intentions of the Germans, and wrote in a letter to the United States State Department that “German leaders, forced by public opinion, and by the von Tirpitz and Conservative parties would take up ruthless submarine warfare again, possibly in the autumn, but at any rate about February or March, 1917.” Gerard was right, and on February 1, 1917, Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, Wilson announced a break in diplomatic relations with the German government, and on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I on the side of the Allies.

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

The non-stop German offensive continued to take its toll throughout the month of April, however, because the majority of American troops in Europe, who were now arriving at a rate of 120,000 a month, were still not sent into battle. In a meeting of the Supreme War Council of Allied leaders at Abbeville, near the coast of the English Channel, which began on May 1, 1918, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and General Ferdinand Foch, the recently named Generalissimo of all Allied forces on the Western Front, was trying hard to persuade Pershing to send all the existing American troops to the front at once. Pershing resisted, reminding the group that the United States had entered the war “independently” of the other Allies, and indeed, the United States would insist during and after the war on being known as an “associate” rather than a full-fledged ally. He further stated, “I do not suppose that the American army is to be entirely at the disposal of the French and British commands.” I’m sure his remarks brought with them, much concern.

On May 2, the second day of the meeting, the debate continued, with Pershing holding his ground in the face of  heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

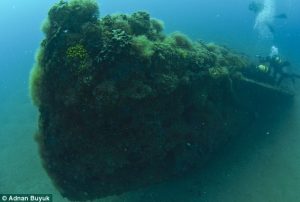

Over the years of shipping and wars on the high seas, the ocean floor has become riddled with ships. They rest on the ocean floors almost like ghosts of the past, but all that is changing. The old wooden boats have most likely rotted away long ago but the metal ships, and those that carried or contained metal, have remained…some, like the World War I ships, for over a hundred years. Nevertheless, time and man have taken their toll on those ships too. Corrosion, sea life, and salvagers have been slowly dismantling these relics, to the point that some are completely gone. It is the natural course, I suppose, but it does seem sad to think that those great battle ships will soon be gone forever. I’m not the only one who feels sadness over that prospect either. As the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I rolled around on July 28, 2014, members of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) met in Belgium to discuss ways of protecting the valuable underwater cultural heritage of the historic war. The organization plans to extend a 2001 convention in order to safeguard thousands more historic sites, including many World War I shipwrecks that are threatened by salvage operations, looting and other brands of destruction. The 2001 convention originally applied only to sites sunk more than 100 years prior to 2001.

Over the years of shipping and wars on the high seas, the ocean floor has become riddled with ships. They rest on the ocean floors almost like ghosts of the past, but all that is changing. The old wooden boats have most likely rotted away long ago but the metal ships, and those that carried or contained metal, have remained…some, like the World War I ships, for over a hundred years. Nevertheless, time and man have taken their toll on those ships too. Corrosion, sea life, and salvagers have been slowly dismantling these relics, to the point that some are completely gone. It is the natural course, I suppose, but it does seem sad to think that those great battle ships will soon be gone forever. I’m not the only one who feels sadness over that prospect either. As the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I rolled around on July 28, 2014, members of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) met in Belgium to discuss ways of protecting the valuable underwater cultural heritage of the historic war. The organization plans to extend a 2001 convention in order to safeguard thousands more historic sites, including many World War I shipwrecks that are threatened by salvage operations, looting and other brands of destruction. The 2001 convention originally applied only to sites sunk more than 100 years prior to 2001.

I suppose that to many people, especially salvagers, these under sea relics mean just one thing…money. But to historians…even amateur historians, like me, it is unthinkable to know that those pieces of history have come to nothing more than a way for looters, or salvagers, as they like to call themselves, to make money. It is much like robbing a grave if you ask me. These places truly are an underwater heritage, and while I’m not against recreational divers going in for a look, they should be required to leave it all as they found it…no  souvenirs. As an avid hiker, I have learned to respect the natural areas I visit, by not stealing from the sites, and not littering either. That way, the next person who visits gets to see the same beautiful sights that I got to see. It should be the same on the ocean floor, and while I don’t see myself visiting any of those historic places, I would like to know that if diving expeditions go there and post videos, it would not be of the leftovers, following a salvage theft.

souvenirs. As an avid hiker, I have learned to respect the natural areas I visit, by not stealing from the sites, and not littering either. That way, the next person who visits gets to see the same beautiful sights that I got to see. It should be the same on the ocean floor, and while I don’t see myself visiting any of those historic places, I would like to know that if diving expeditions go there and post videos, it would not be of the leftovers, following a salvage theft.

With technology getting better and better, the locations of many, if not most of the undersea relics are well known, and unfortunately that also leaves them vulnerable to looting. I suppose it will still happen, even with increased regulation against it, but maybe some people would be deterred. That is the goal anyway. According to UNESCO’s Ulrike Guerin, protection under the convention “prevents the pillaging, which is happening on a very large scale, it prevents the commercial exploitation, the scrap metal recovery, and it will have regulations on the incidental impacts, such as the problem of trawlers going over World War I sites.” After so many years underwater, these ships are already fragile. It’s up to us, the people of the world to step up now, and protect them to the best of our ability. We may not be able to protect them from the ravages of the salt water, the sea life, and the years, but we can do our best to protect then from the salvagers, thieves, and looters of the world, who might go to the sight for the sole purpose of their own profit…at the expense of the people of the world.

The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage, introduced in 2001 was designed to help member nations better protect shipwrecks, submerged ruins and other valuable, increasingly fragile, parts  of their underwater heritage. The organization estimates that there are more than 3 million undiscovered shipwrecks scattered over the globe, including more than 12,500 sailing ships and war vessels lost at sea between 1824 and 1962 alone. With improved technology, these wrecks are becoming more accessible all the time, making them vulnerable to treasure hunters, commercial salvage operations and other types of looting…destroying these treasures for their own selfish, greedy gain. In my opinion, their preservation is more than just a good idea…it is our duty, and not only concerning World War I era wrecks, but also World War II era, and many other historic ship wrecks that could be photographed by legitimate expeditions for all to see.

of their underwater heritage. The organization estimates that there are more than 3 million undiscovered shipwrecks scattered over the globe, including more than 12,500 sailing ships and war vessels lost at sea between 1824 and 1962 alone. With improved technology, these wrecks are becoming more accessible all the time, making them vulnerable to treasure hunters, commercial salvage operations and other types of looting…destroying these treasures for their own selfish, greedy gain. In my opinion, their preservation is more than just a good idea…it is our duty, and not only concerning World War I era wrecks, but also World War II era, and many other historic ship wrecks that could be photographed by legitimate expeditions for all to see.

The United States is often called the Sleeping Giant. In the past, the United States has been known as the most powerful country in the world…back in the good old days, that is. Now China, Japan and Russia are also considered to be powerful countries where nuclear weaponry is concerned. The dollar was also the powerful currency, then and even now. The president of the United States was always considered the most powerful person, and I think still is today, or is moving back into that position. All these things considered, the United States was definitely a sleeping giant, because if it woke up it would do everything in its power to rectify things around the globe. As we saw on September 11, 2001, when terrorists attacked our country. Like Toby Keith sang in his song Courtesy Of The Red, White, And Blue (The Angry American), “Justice will be served, and the battle will rage. This big dog will fight when you rattle his cage. And you’ll be sorry that you messed with the U.S. of A” That is notoriously the way the United States has been when it comes to world conflict…slow to anger, but once we are in a war…we are in it to win it!

The United States is often called the Sleeping Giant. In the past, the United States has been known as the most powerful country in the world…back in the good old days, that is. Now China, Japan and Russia are also considered to be powerful countries where nuclear weaponry is concerned. The dollar was also the powerful currency, then and even now. The president of the United States was always considered the most powerful person, and I think still is today, or is moving back into that position. All these things considered, the United States was definitely a sleeping giant, because if it woke up it would do everything in its power to rectify things around the globe. As we saw on September 11, 2001, when terrorists attacked our country. Like Toby Keith sang in his song Courtesy Of The Red, White, And Blue (The Angry American), “Justice will be served, and the battle will rage. This big dog will fight when you rattle his cage. And you’ll be sorry that you messed with the U.S. of A” That is notoriously the way the United States has been when it comes to world conflict…slow to anger, but once we are in a war…we are in it to win it!

The same held true for the other wars we have been in. We might not jump in early, but when we do…look out. On this day, April 6, 1917, the United States Senate voted 82 to 6 to declare war against Germany, the United  States House of Representatives endorses the declaration by a vote of 373 to 50, and America formally entered World War I. This action would be the one that would send my grandfather, George Byer to war. He was 24 years old. Grandpa didn’t talk much about his time in the war…at least not that I remember. I think that most of the men who came home after fighting in a war, are just happy to be home. They want to put it all behind them, and move forward with their lives, knowing that if it was ever necessary he would go back again. He was a patriot, and that was what patriots did. In fact, when the time came for the men to register for the “old man draft” of World War II…a time when men up to the age of 65 were required to register for the draft, Grandpa was honored to register, as were the other men between the ages of 45 and 65. These men felt like their time of usefulness was over, and when they were told that they were needed again, even if it was just for work on the home front, they all jumped at the chance to serve.

States House of Representatives endorses the declaration by a vote of 373 to 50, and America formally entered World War I. This action would be the one that would send my grandfather, George Byer to war. He was 24 years old. Grandpa didn’t talk much about his time in the war…at least not that I remember. I think that most of the men who came home after fighting in a war, are just happy to be home. They want to put it all behind them, and move forward with their lives, knowing that if it was ever necessary he would go back again. He was a patriot, and that was what patriots did. In fact, when the time came for the men to register for the “old man draft” of World War II…a time when men up to the age of 65 were required to register for the draft, Grandpa was honored to register, as were the other men between the ages of 45 and 65. These men felt like their time of usefulness was over, and when they were told that they were needed again, even if it was just for work on the home front, they all jumped at the chance to serve.

As for World War I, Grandpa would serve, and he would come home. Then, he would go on to live a long life… forever changed from the man he once was, because you see, war changes a man. They are changed by what they see, whether they were required to take a life or not. And if they were required to kill, then kill they would, because The Sleeping Giant had been awakened, and the Big Dog’s cage had been rattled. The United States would go to war, and they would win, along with their alleys, because losing was not an option…not if the world was to remain the kind of place we knew and loved. Germany was an evil empire, and that evil empire had to be stopped. I am very proud of my grandfather’s service, and I’m thankful that the Big Dog fought in this one and the other wars it has fought in. It was an important fight, and we needed to win it.

forever changed from the man he once was, because you see, war changes a man. They are changed by what they see, whether they were required to take a life or not. And if they were required to kill, then kill they would, because The Sleeping Giant had been awakened, and the Big Dog’s cage had been rattled. The United States would go to war, and they would win, along with their alleys, because losing was not an option…not if the world was to remain the kind of place we knew and loved. Germany was an evil empire, and that evil empire had to be stopped. I am very proud of my grandfather’s service, and I’m thankful that the Big Dog fought in this one and the other wars it has fought in. It was an important fight, and we needed to win it.

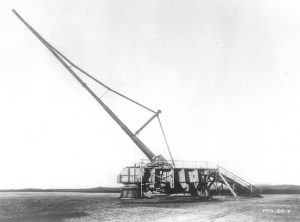

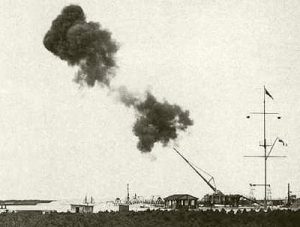

It seems as if the nations will never be satisfied until they have a new and stronger weapon that will easily destroy a massive amount of people in one shot. Wars are a part of life here on Earth, and will be until the end of time, so we might as well get used to that fact. World War I was not a different time when it comes to weapons of war, in fact on March 23, 1918 at 7:20am, an explosion took place in the Place de la Republique in Paris, and it hailed the first attack of a new German gun. The Pariskanone, Paris-Geschütz, or Paris gun, as it came to be known, was manufactured by Krupps. The Pariskanone was 210mm, with a 118-foot-long barrel. It could fire a shell an impressive distance of some 130,000 feet…25 miles into the air. Three of them fired on Paris that day from a gun site at CrÉpy-en-Laonnaise, a full 74 miles away. The city of Paris was reeling. Paris had withstood all earlier attempts at its destruction, including scattered bombings, but this would be different. It was first thought by the Paris Defense Service, that the city was being bombed, but soon they determined that it was actually being hit by artillery fire. It was a previously unimagined situation. I’m sure everyone wondered how the Germans could have made such a weapon.

It seems as if the nations will never be satisfied until they have a new and stronger weapon that will easily destroy a massive amount of people in one shot. Wars are a part of life here on Earth, and will be until the end of time, so we might as well get used to that fact. World War I was not a different time when it comes to weapons of war, in fact on March 23, 1918 at 7:20am, an explosion took place in the Place de la Republique in Paris, and it hailed the first attack of a new German gun. The Pariskanone, Paris-Geschütz, or Paris gun, as it came to be known, was manufactured by Krupps. The Pariskanone was 210mm, with a 118-foot-long barrel. It could fire a shell an impressive distance of some 130,000 feet…25 miles into the air. Three of them fired on Paris that day from a gun site at CrÉpy-en-Laonnaise, a full 74 miles away. The city of Paris was reeling. Paris had withstood all earlier attempts at its destruction, including scattered bombings, but this would be different. It was first thought by the Paris Defense Service, that the city was being bombed, but soon they determined that it was actually being hit by artillery fire. It was a previously unimagined situation. I’m sure everyone wondered how the Germans could have made such a weapon.

Before the day was over, the shelling had killed 16 people and wounded 29 more. The Germans continued the shelling of that year in several phases between March 23 and August 9, 1918. Over that time, the gun caused a total of 260 deaths in Paris. It was a low number due to the fact that the residents of Paris quickly learned to avoid gathering in large groups during periods of shelling. With less people in each area, the casualties were limited substantially. Nevertheless, the weapon had a terrifying effect on the people and a horrific impact on property in the areas of the shelling. Almost all information about the Pariskanone, one of the most sophisticated weapons to emerge out of World War I, disappeared after the war ended. Later, the Nazis tried

without success to reproduce the gun from the few pictures and diagrams that remained. Copies were deployed in 1940 against Britain across the English Channel, but failed to cause any significant damage….a good thing for the people of the Britain at that time. When I look at the pictures of the weapon, I am reminded of the old “Wild, Wild, West” show. There always seemed to be some strange new fangled weapon of destruction in use there too.

without success to reproduce the gun from the few pictures and diagrams that remained. Copies were deployed in 1940 against Britain across the English Channel, but failed to cause any significant damage….a good thing for the people of the Britain at that time. When I look at the pictures of the weapon, I am reminded of the old “Wild, Wild, West” show. There always seemed to be some strange new fangled weapon of destruction in use there too.

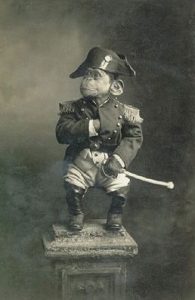

When World War I broke out, many young men were called into service. It is a common part of war…one we all know about, and most parents dread. World War I was unique in one way, however. There was a soldier who went to war who was different. He was not different in the way he served exactly, but rather in some other very obvious ways. His speech was different. His mentality was somewhat different, and his looks were different. I’m not being discriminatory, but simply stating a fact. His name was Jackie, and he was different because he was a monkey, well actually, he was a Chacma baboon (Papio ursinus). Jackie was found in August 1915 near the Marr’s family farm in Villeria, Pretoria, South Africa by Albert Marr and soon became a beloved pet.

When World War I broke out, many young men were called into service. It is a common part of war…one we all know about, and most parents dread. World War I was unique in one way, however. There was a soldier who went to war who was different. He was not different in the way he served exactly, but rather in some other very obvious ways. His speech was different. His mentality was somewhat different, and his looks were different. I’m not being discriminatory, but simply stating a fact. His name was Jackie, and he was different because he was a monkey, well actually, he was a Chacma baboon (Papio ursinus). Jackie was found in August 1915 near the Marr’s family farm in Villeria, Pretoria, South Africa by Albert Marr and soon became a beloved pet.

When the war started and the young men were drafted, Albert was no exception. The thing is that Albert couldn’t stand the thought of leaving his beloved pet at home. Albert was assigned to service at Potchefstroom in the North West province of South Africa as private number 4927 for the newly formed 3rd Transvaal Regiment of the 1st South African Infantry Brigade on the 25th August 1915. He approached his superiors and requested that Jackie be allowed to go with him and amazingly was given permission. I’m sure that seems as odd to you as it did to me, but it goes further. Once enlisted Jackie was given a special uniform complete with buttons, a cap, regimental badges, a pay book and his own rations. He was a true member of the regiment, but that doesn’t mean he was accepted as a part of it…at first anyway. The other members of the regiment initially ignored Jackie, but like most people around a monkey, or in this case, baboon, it was hard to ignore him for very long. Jackie soon became the official mascot of the 3rd Transvaal Regiment. Jackie took his duties very seriously, however. He wasn’t there just to eat and fool around!

Jackie was very smart, and when he saw a superior officer passing, he would stand to attention and even provide them with the correct salute. He would light cigarettes for his comrades in arms and was, without a doubt, the best sentry around, due to his great senses of hearing and smelling which allowed him to be able to detect any enemy long before any of his other army mates could even notice their approach. He wasn’t a coddled pet protected for the battles either. Jackie spent three years in the front line amongst the trenches of France and Flanders in Europe. During the Senussi Campaign on 26 February 1916 in Egypt, Jackie’s beloved Albert got wounded on his shoulder by an enemy bullet. Jackie stayed beside him until the stretcher bearers arrived, licking the wound and doing what he could to comfort his friend.

Albert and Jackie both held the rank of private, and in April of 1918, both got injured in the Passchendaele area in Belgium during a heavy fire. With explosions surrounding them, Jackie was seen trying to get some protection by building a little fortress of stones around himself. He didn’t manage to finish his little safe area soon enough, and was hit by a chunk of shrapnel from a shell explosion nearby, which also injured Albert. Jackie’s right leg was seriously wounded and later had to be amputated. Jackie and Albert both made a full recovery and shortly before the armistice, Jackie was promoted to corporal, and awarded a medal for valor.

At the end of April, Jackie was officially discharged at the Maitland Dispersal Camp, Cape Town, South Africa, while wearing on his arm a gold wound stripe and three blue service chevrons indicating three years of frontline service. He was given a parchment discharge paper, a military pension and a Civil Employment Form for

discharged soldiers. After his service, Jackie returned to the Marr’s farm where he lived until May 22, 1921…a sad day for all who knew him. Albert Marr lived until the age of 84 and died in Pretoria in August 1973. Jackie was an amazing Chacma Baboon who, because of a fateful connection, ended up as the only monkey to reach the rank of Corporal of the South African Infantry and fight in Egypt, Belgium and France during World War I. Now that’s amazing!!!

discharged soldiers. After his service, Jackie returned to the Marr’s farm where he lived until May 22, 1921…a sad day for all who knew him. Albert Marr lived until the age of 84 and died in Pretoria in August 1973. Jackie was an amazing Chacma Baboon who, because of a fateful connection, ended up as the only monkey to reach the rank of Corporal of the South African Infantry and fight in Egypt, Belgium and France during World War I. Now that’s amazing!!!

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In the summer of 1914, the Dresden was patrolling the Caribbean Sea. Its assignment was to safeguard German investments and German citizens living abroad in the region. Then, on July 20, during a bitter civil war in Mexico, the Dresden was called upon to give safe passage to Mexican president, Victoriano Huerta, by transporting him and his family as they escaped to Jamaica, where they received asylum from the British government. Then came news from Europe of Austria’s ultimatum to Serbia and the imminent possibility of war. The German’s put the fleet on alert. By the first week of August the nations of Europe were at war. The Dresden was sent to South America to attack British shipping interests there, and it sunk several merchant ships as it traveled to Cape Horn, at the southern tip of Chile. The Dresden eluded the British naval squadron in  the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

Just five weeks later, the Dresden was the only German ship to escape destruction at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on November 8, when the British light cruisers Inflexible and Invincible, commanded by Sir Doveton Sturdee, sank four of von Spee’s ships. Lost were Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Leipzig and Nurnberg. As a crew member of Dresden wrote later of watching one of the other ships sink, “Each one of us knew he would never see his comrades again, no one on board the cruiser can have had any illusions about his fate.” Then the Dresden escaped under cover of bad weather south of the Falkland Islands.

Dresden consistently avoided capture by the British navy over the next several months, while sinking a number of cargo ships and then seeking refuge in the network of channels and bays in southern Chile. In need of repairs, the Dresden put into an island off the Chilean coast, in Cumberland Bay on March 8th. Captain, Fritz Emil von Luedecke, had decided the repairs were necessary in the wake of such heavy and extended use. Captain von Luedecke sent out many messages asking for fuel in the hopes of reaching any passing coal ships in the area, but the messages were picked up the British ships, Kent and Glasgow six days later. After a  hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.

hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.

As a girl, I like many other girls became a Girl Scout. It was a group of girls having fun, while learning things and earning badges. The group was founded on March 12, 1912, and turns 105 years old today. The organization, called Girl Scouts, was founded in Savannah, Georgia by a woman named Juliette Gordon Low. She was born in 1860, and became a widow in 1905. She needed something…a cause. She had suffered through a bad marriage to a man who cheated on her and left most of his estate to his mistress. She wanted to help young women become self-sufficient…a cause borne out of her own experiences of feeling defined by the era’s roles for women, so she came up with the idea of a group that would teach young women about their worth and abilities. She first worked with a Scottish organization called Girl Guides and then founded the first American branch of the group in 1912, but she decided to break away and further develop her young women’s scouting association on her own. She soon changed the organization’s name to the Girl Scouts, and became the organization’s first president.

As a girl, I like many other girls became a Girl Scout. It was a group of girls having fun, while learning things and earning badges. The group was founded on March 12, 1912, and turns 105 years old today. The organization, called Girl Scouts, was founded in Savannah, Georgia by a woman named Juliette Gordon Low. She was born in 1860, and became a widow in 1905. She needed something…a cause. She had suffered through a bad marriage to a man who cheated on her and left most of his estate to his mistress. She wanted to help young women become self-sufficient…a cause borne out of her own experiences of feeling defined by the era’s roles for women, so she came up with the idea of a group that would teach young women about their worth and abilities. She first worked with a Scottish organization called Girl Guides and then founded the first American branch of the group in 1912, but she decided to break away and further develop her young women’s scouting association on her own. She soon changed the organization’s name to the Girl Scouts, and became the organization’s first president.

Low hoped to give her girls the opportunity to grow physically, mentally, emotionally, and even spiritually, Low  started the organization with just 18 girls in attendance at that first meeting. Low was an athlete, as well as an art lover. Her dream was to teach the girls that they could do anything. She wanted her girls to find out that they could help out in so many ways, and she definitely proved that. The Girl Scouts of America were very involved with the war effort back home during both World War I and World War II. They sold war bonds, collected peach pits for gas masks…peach pits were used as filters, worked in hospitals, and provided hands-on support to the country and the troops. Then, during the 1930s, when the Great Depression hit, the Girl Scouts again stepped up to the plate, collecting clothing and canned goods for the poor, making them quilts, providing meals for impoverished children, and helping out at hospitals.

started the organization with just 18 girls in attendance at that first meeting. Low was an athlete, as well as an art lover. Her dream was to teach the girls that they could do anything. She wanted her girls to find out that they could help out in so many ways, and she definitely proved that. The Girl Scouts of America were very involved with the war effort back home during both World War I and World War II. They sold war bonds, collected peach pits for gas masks…peach pits were used as filters, worked in hospitals, and provided hands-on support to the country and the troops. Then, during the 1930s, when the Great Depression hit, the Girl Scouts again stepped up to the plate, collecting clothing and canned goods for the poor, making them quilts, providing meals for impoverished children, and helping out at hospitals.

During my time in the Girl Scouts, I can’t say that I did anything that was as life changing as the Girl Scouts of days gone by, but I did enjoy my time as a scout. We learned many skills that earned us badges to wear on our sash, and some of those skills are still things I use today. The camaraderie that I felt as a Girl Scout was amazing. Some of the best friendships of my childhood were formed in those meetings. Those are years I will never forget, and I owe it all to Juliette Gordon Low, and her inspired ideas about what girls could be. Juliette Gordon Low died of breast cancer in 1927, in her Savannah, Georgia home. She was 66 years old. It was her request that she be buried in her Girl Scout uniform, because her years with the Girl Scouts were truly the happiest hears of her life. She also requested that a telegram from the National Board of Girl Scouts of the USA be placed in her pocket. It read, “You are not only the first Girl Scout, you are the best Girl Scout of them all.”