union

When you think about the Civil War, you think of battles being fought back east…right? For the most part, it was. When the war began, there were 34 states, but by the end, there were 36 states. Of course, some of the Southern states, eleven to be exact, wanted to secede and form their own country. That was partly what the war was about. The Southern states wanted to keep slavery, and the Northern states did not, and because they could not agree, eleven states chose to secede, and the rest fought to keep our nation together.

When you think about the Civil War, you think of battles being fought back east…right? For the most part, it was. When the war began, there were 34 states, but by the end, there were 36 states. Of course, some of the Southern states, eleven to be exact, wanted to secede and form their own country. That was partly what the war was about. The Southern states wanted to keep slavery, and the Northern states did not, and because they could not agree, eleven states chose to secede, and the rest fought to keep our nation together.

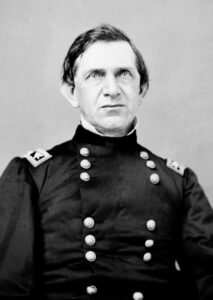

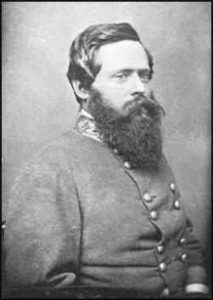

Some of the battles were fought, however on the far western front. The first of those battles, was on February 21, 1862. In the Battle of Valverde, Confederate troops under General Henry Hopkins Sibley attacked Union troops commanded by Colonel Edward R S Canby near Fort Craig in the New Mexico Territory. This first major engagement of the Civil War in the far West, produced heavy casualties but ended with no decisive result. Of course, the battle was part of the broader movement by the Confederates to capture New Mexico and other parts of the West. The point was to secure territory that the Rebels thought was rightfully theirs, because it was part of the southern territories of the United States. This area had been denied them by political compromises made before the Civil War, which they felt was wrong.

By this time, the Confederacy was quickly going broke, and they wanted to use Western mines to fill its treasury. The Rebel troops moved from San Antonio, into southern New Mexico, which at that time included Arizona, and captured the towns of Mesilla and Tucson. Sibley, with 3,000 troops, now moved north against the Federal stronghold at Fort Craig on the Rio Grande. Canby was determined to make sure the Confederates didn’t lay siege to Fort Craig. Canby knew that the Rebels were running low on supplies, and they wouldn’t last much longer. He knew that Sibley really did not have sufficiently heavy artillery to attack the fort, so when Sibley arrived near Fort Craig on February 15, he ordered his men to swing east of the fort, cross the Rio Grande, and capture the Valverde fords of the Rio Grande. He hoped to cut off Canby’s communication and force the Yankees out into the open, thereby giving the Rebels the upper hand.

For Sibley’s Rebels, things at the fords didn’t initially go as planned. Five miles north of Fort Craig, a Union detachment attacked part of the Confederate force. The Yankees pinned the Texan Rebels in a ravine and were on the verge of routing them when more of Sibley’s men arrived and turned the tide. Sibley’s second in command, Colonel Tom Green, who was filling in for Sibley, who was ill, made a bold counterattack against the Union left flank. The Yankees retreated, heading back to Fort Craig. Sibley’s men didn’t take Fort Craig either.

During the Battle of Valverde, out of 3,100 men, the Union suffered 68 killed, 160 wounded, and 35 missing.

The Confederates suffered 31 killed, 154 wounded, and 1 missing out of 2,600 troops. The battle was indeed bloody, but none of their objectives were accomplished, so it was virtually an indecisive battle. From Fort Craig, Sibley’s men continued up the Rio Grande winning battle after battle. Nevertheless, after capturing Albuquerque and Santa Fe, they were stopped at the Battle of Glorieta Pass on March 28, 1862.

The Confederates suffered 31 killed, 154 wounded, and 1 missing out of 2,600 troops. The battle was indeed bloody, but none of their objectives were accomplished, so it was virtually an indecisive battle. From Fort Craig, Sibley’s men continued up the Rio Grande winning battle after battle. Nevertheless, after capturing Albuquerque and Santa Fe, they were stopped at the Battle of Glorieta Pass on March 28, 1862.

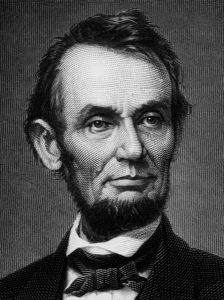

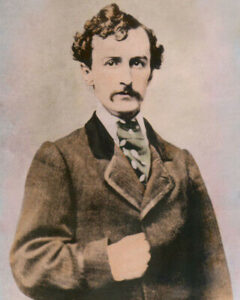

John Wilkes Booth was an actor, and as such, he had an expectation of applause following a performance. That is just what he thought the assassination of President Lincoln was. No, he didn’t think it was fake. He knew he was murdering the President of the United States, but he somehow thought people would consider it one of his greatest performances…the crowning moment of his stage career. It never occurred to him that the people who had loved him as an actor would suddenly turn against him.

John Wilkes Booth was an actor, and as such, he had an expectation of applause following a performance. That is just what he thought the assassination of President Lincoln was. No, he didn’t think it was fake. He knew he was murdering the President of the United States, but he somehow thought people would consider it one of his greatest performances…the crowning moment of his stage career. It never occurred to him that the people who had loved him as an actor would suddenly turn against him.

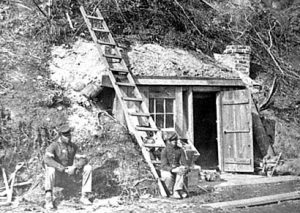

At the very least, he expected to be greeted with applause and support by those sympathetic to the Confederacy. Instead, he found, much to his shock and great dismay, that he was a hounded man, and few wanted to associate with him. Oh, the loyalists to the Confederacy did their duty by him, but with great reluctance. He first encountered this reaction when he and David Herold, who was an American pharmacist’s assistant and Wilkes accomplice in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, stumbled upon a man in the dark, while searching for the home of Colonel Cox. The man, a local named Oswell Swann, reluctantly agreed to guide then to the Cox home, but only if he received payment for his services. He considered it just reward for the risk he was taking. Afterward, Swann collected his fee and vanished into the night, leaving the fugitives to the “hospitality” of Colonel Cox. That “hospitality” consisted of a few supplies, including whiskey, and a servant to lead the men to a hiding place in the woods. Cox certainly didn’t want these men to be found in his house.

Cox informed Booth that he was to “remain hidden in the woods until contacted.” Then Cox sent for Thomas Jones, a Confederate agent with experience in smuggling spies and information across the Potomac River into Virginia. Jones agreed to get them out and guide them across the Potomac, for a fee, but when he visited the fugitives in the woods, where they hid in a pine thicket, he told them it would be several days before he could do so. The manhunt for Booth and Herold was massive. Federal troops combed the area, searching properties and interrogating citizens over whether they had seen two men traveling together. Booth was very distressed, because instead of receiving the expected support and appreciation of the south, Booth found himself confined to a pine thicket!! Jones provided the men with newspapers, from which Booth discovered that he was widely considered a villainous murderer, rather than the Confederate hero he had expected to be. He wrote about his “horrible” fate, and the “injustice” of it all, in a diary he kept in an appointment book.

Federal authorities had most of the conspirators who had planned to kidnap Abraham Lincoln in custody by April 20, 1865. Several were not party to the assassination, but because they were involved in the kidnapping plans, they were held anyway. Three men were still not in custody…Booth, Herold, and John Surratt remained at large. The War Department put out wanted poster, released in Washington on April 20, offering a $50,000 reward for Booth, and $25,000 apiece for Herold and Surratt. By then, Surratt was hiding out in Canada, even though he knew that his mother was being held in federal custody. Coward that he was, Surratt was making plans to flee to Europe. Booth and Herold continued to cower in a pine thicket, relatively helpless. They didn’t dare leave, because they would be seen and immediately arrested. A dejected Booth spent his time drinking whiskey and scribbling in his makeshift diary over the unfairness of his reception. He believed his action had made him a martyr to the Confederate cause.

When the fugitives finally attempted to cross the Potomac, on about April 21, Jones’s guidance consisted of verbal instructions directing them to a waiting boat. These men had no boating experience, and the night was windy. The tides and swift current didn’t help matters either. Nor did the gunboats in the area. Booth whined into his diary, “last night being chased by gunboats till I was forced to return wet, cold, and starving.” Needless to say, the crossing was a failure, but Booth’s overly dramatic entry exaggerated what may have been an encounter with USS Juniper, positioned in the river near their point of crossing. Juniper’s log did not include a report of chasing anything that night. Booth likely spotted the gunboat, and in a panic, returned to the Maryland shore. Booth’s fugitive days ended when he was caught on April 26, 1865, near Port Royal, Virginia. As Booth and his co-conspirator, David Herold, cowered inside a barn, the soldiers demanded that they surrender. John Wilkes Booth died in agonizing fashion at the hands of Union soldiers in Port Royal, Virginia,

two weeks after he assassinated Abraham Lincoln. When the Union soldiers demanded their surrender, Herold complied. But Booth refused. He didn’t leave the barn until one of the soldiers set it on fire. As he tried to sneak out in the shadows and flame, a shot cracked through the silent night…and found its mark. Booth briefly held on to life, but in the end, the bullet would be his demise…in true disgraced style.

two weeks after he assassinated Abraham Lincoln. When the Union soldiers demanded their surrender, Herold complied. But Booth refused. He didn’t leave the barn until one of the soldiers set it on fire. As he tried to sneak out in the shadows and flame, a shot cracked through the silent night…and found its mark. Booth briefly held on to life, but in the end, the bullet would be his demise…in true disgraced style.

War is a really horrific thing for soldiers to go through, and closure comes in different forms for different soldiers. Returning to the battlefield is a way to find closure for many veterans. It is also a way for solders to keep the friendships they made at a time when their life depended on their fellow soldiers. Countless numbers of men have returned to places like the beaches of Normandy, France to see that place again, where so many lost their lives. Some soldiers didn’t leave the place they fought in their war. Vietnam was that way to a degree.

War is a really horrific thing for soldiers to go through, and closure comes in different forms for different soldiers. Returning to the battlefield is a way to find closure for many veterans. It is also a way for solders to keep the friendships they made at a time when their life depended on their fellow soldiers. Countless numbers of men have returned to places like the beaches of Normandy, France to see that place again, where so many lost their lives. Some soldiers didn’t leave the place they fought in their war. Vietnam was that way to a degree.

The Civil War was unique in that when the veterans decided to have their reunion, they wanted to, of course renew old friendships with those they shared a common bond, but they also wanted to make their reunion a way to bring the north and south back together again. The Gettysburg, Pennsylvania reunion was the largest of these events, and so made headline news around the world. The event took place in 1913 at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The Civil War was unique in that all participants were citizens of the United States. Brother fought against brother, and family members against family members. The reunion was a chance to repair those horribly broken relationships for all the men who were still alive at the reunion, which was held on the 50th anniversary of the battle. General H.S. Huidekoper, a Gettysburg Veteran of the 150th PA., was the man behind the idea of making it a gathering of both Northern and Southern Veterans on the 50th Anniversary of the battle. With the state of Pennsylvania, acting as host, $400,000 was set aside to finance the event. The Federal Government added $195,000 and the volunteer services of 1,500 officers and enlisted men. The event was five years in the planning, with Veteran groups throughout the nation helping to make it happen.

The Veterans who were still alive were aging, and because of the reunion, they were able not only to renew the friendships they had, but new friendships were born, and old wounds healed as well. The youngest Veteran, Colonel John C. Clem (known as the Shiloh drummer boy), was 62 years old. The oldest Veteran was 112 years of age. A total of 55,000 veterans attended the event, representing the half million living Confederate and Union Veterans. Of the 55,000 men, 22,103 came from Pennsylvania, and of those, 303 were Confederate. The smallest delegation came from New Mexico…one, a Union Veteran.

The event…one I wish I could have seen, saw over 5,000 tents, covering 280 acres in the middle of the battlefield, where so many had lost their lives. It was almost as if they were there too…giving their approval. Distinguished guests had come to give speeches and presentations. General Daniel Sickles, representing the III Corps at Gettysburg where he lost his leg, was the only corps commander present. On behalf of the battle leaders were the daughter of General Meade and the grandchildren of Generals Longstreet, A.P. Hill and Pickett.

The reunion lasted a full week. The men ate well and swapped stories, cried and laughed. In all 688,000 meals were served by two thousand cooks and helpers. Amazingly and considering the age and health of the Veterans, along with the hot, sultry weather, there were only nine Veterans who did not survive the week, a number well below the normal mortality rate for that day. Perhaps it was the exhilaration of the joining of old friends, reliving days of their youth, hearing the infamous Rebel Yell resound across the battlefield, or reenacting Pickett’s charge to have the Stars and Bars meet the trefoil of Hancock’s II Corps once more that had lengthened their lives.

In the most stunning moment of the event…on the fourth of July at high noon, a great silence fell over the battlefield, as the church bells began to toll. Buglers of the blue and gray prepared to play the mournful tune of Taps one last time. The guns of Gettysburg shook the ground, signaling the end of the weeklong event. When I visited Gettysburg many years later, I was surprised by exactly how that place felt. You could feel the atmosphere there all those years later. It is hallowed ground. You feel like you should whisper…or better yet just be silent. I have never felt that way before, or since.

And though many eloquent speeches were given at Gettysburg that week, none expressed what these Veterans took away from this experience better than a scene witnessed at the train station: “Nearly all of the men had said their good-byes and headed for home. On the station platform a former Union soldier from Oregon and a Louisiana Confederate were taking leave of each other. They shook hands and embraced, but neither seemed

able to find the words to express his feelings. Then an idea seemed to strike both men at once. In a simple act, which seemed to say everything they felt the pair took off their uniforms and exchanged them. The Yankee went home in Rebel gray, the Confederate in Union blue.” The above quote is an excerpt from “Gettysburg: The 50th Anniversary Encampment,” by Abbott M. Gibney, Civil War Times Illustrated, October 1970.

able to find the words to express his feelings. Then an idea seemed to strike both men at once. In a simple act, which seemed to say everything they felt the pair took off their uniforms and exchanged them. The Yankee went home in Rebel gray, the Confederate in Union blue.” The above quote is an excerpt from “Gettysburg: The 50th Anniversary Encampment,” by Abbott M. Gibney, Civil War Times Illustrated, October 1970.

Prior to the Civil War, and even for years afterward, the black man was considered first a non-human, and secondly not very intelligent. Because of that, it was thought that the black soldiers would not be able to handle real combat situations. Nevertheless, the Union Army needed their help, and so they would have to take a chance on the black soldiers along the James River in the spring of 1864. My guess is that it was a rather tense moment when the Federal Soldiers faced off the Rebels on May 24, 1864. They stood behind the walls they had built with their own hands, and watched as the dismounted Rebel cavalry charged toward them. With their rifles trained on the enemy troops, each man knew that this was their chance to prove themselves. They were a brigade of mostly black soldiers, and it was vital that they be able to hold their own against an enemy who outnumbered them two to one. As well as an enemy who was party to their years of slavery.

Prior to the Civil War, and even for years afterward, the black man was considered first a non-human, and secondly not very intelligent. Because of that, it was thought that the black soldiers would not be able to handle real combat situations. Nevertheless, the Union Army needed their help, and so they would have to take a chance on the black soldiers along the James River in the spring of 1864. My guess is that it was a rather tense moment when the Federal Soldiers faced off the Rebels on May 24, 1864. They stood behind the walls they had built with their own hands, and watched as the dismounted Rebel cavalry charged toward them. With their rifles trained on the enemy troops, each man knew that this was their chance to prove themselves. They were a brigade of mostly black soldiers, and it was vital that they be able to hold their own against an enemy who outnumbered them two to one. As well as an enemy who was party to their years of slavery.

The battle the black troops were about to fight was a small part of Lieutenant General Ulysses S Grant’s Overland Campaign. The goal was to cripple the Confederate capital, and in doing so, bring down the Confederacy before the end of 1864. The Army of the James consisted of the X and XVIII Corps. About 40% of the army’s 33,000 men were black. Butler was confident his “colored troops” would do all the Union hoped and more, because he realized they viewed their service as a chance to gain rights they had never had before for themselves and for their families…making blacks free and equal to whites. Of course, fear of capture and a return to slavery, was a great motivator to win this battle and the war too. In early May, Butler and his army left Fort Monroe at the mouth of the James River and drove upriver toward Bermuda Hundred, about 14 miles south of Richmond. The general believed this was a better position to attack the capital from this strip of land, which lies at the point where the Appomattox River meets the James. From there, Butler’s forces could disable rail transportation south of Richmond and with it, communication between the capital and points south.

Late on the afternoon of May 5, a week before the army’s planned arrival on Bermuda Hundred, Butler reported to Grant that Brigadier General Edward A. Wild’s brigade of black troops had captured these two sites without opposition. Their arrival, Butler wrote, was “apparently a complete surprise” to the Confederates. The sight of former slaves coming ashore at Wilson’s Wharf must have almost terrified local planters, because many of the troops had once been held in bondage in the surrounding area. It could feel very intimidating to think of the former slaves motive for revenge. Shortly after the brigade’s arrival, the soldiers captured William Clopton, a wealthy planter known for his brutality. Wild, with his profound hatred of slavery, ordered his men to tie Clopton to a tree and expose his back. Then Wild ordered William Harris of Company E forward to flog his former master, Cheers echoed through the African Brigade. “Mr. Harris played his part conspicuously,” Sergeant Hatton recalled, “bringing the blood from his loins at every stroke, and not forgetting to remind the gentleman of the days gone by.” Wild described the lashing of Clopton to Hinks as “the administration of

Poetical justice.” The fears of the plantation owners were realized that day, but whipping the planters was the least of Wild’s concerns at Wilson’s Wharf. He immediately put his troops to work on an earthwork fortification on a bluff over the James and named it Fort Pocahontas. The walls held against Confederates, and the Union would go on to win the Civil War, but no one would again be able to say that the black soldiers couldn’t do their job, nor would they ever doubt the depth of their rage over the cruel treatment they had been subjected to by the slave owners.

Poetical justice.” The fears of the plantation owners were realized that day, but whipping the planters was the least of Wild’s concerns at Wilson’s Wharf. He immediately put his troops to work on an earthwork fortification on a bluff over the James and named it Fort Pocahontas. The walls held against Confederates, and the Union would go on to win the Civil War, but no one would again be able to say that the black soldiers couldn’t do their job, nor would they ever doubt the depth of their rage over the cruel treatment they had been subjected to by the slave owners.

These days, with all the television shows about secret agents, undercover cops, and spies, most of us wouldn’t think twice about one of those positions being held by a woman. During the American Civil War, however, which basically coincided with the Victorian era, one of the most morally repressive eras in history for women, things were different. Everything from a woman’s dress to her education were tightly constricted by moral attitudes that governed her every action. Basically, women were to concentrate their “war efforts” on the task of supporting their husband, brothers, or fathers, in whatever their beliefs were toward the matter. However, as the war dragged on and more men were called into active duty, the farms, factories, stores, and schools were left without workers, so the women stepped up to stand in the gap, as it were. This was most surprising because, back then, women were considered too frail, and their minds too simple for things like politics and war. They were designed for keeping the home and taking care of the babies. Nevertheless, when the men were called into active duty, most of them would have lost their farms, homes, and businesses had it not been for the strength and intelligence of the of the “frail and simple” women. Many women refused to limit their assistance to their country to what could be accomplished close to home. Some of them became nurses, worked to raise supplies for their troops, or even worked in armories, but there was a number of these women decided to support their country in a more dangerous…and scandalous way…they became spies.Back then, espionage was considered a very dishonorable pursuit for a man during the Civil War era, but for a woman…it was tantamount to prostitution. Nevertheless, with the war raging, women of both the North and South flaunted the Victorian morality of the time to provide their country the intelligence it needed to make tactical and practical decisions.

These days, with all the television shows about secret agents, undercover cops, and spies, most of us wouldn’t think twice about one of those positions being held by a woman. During the American Civil War, however, which basically coincided with the Victorian era, one of the most morally repressive eras in history for women, things were different. Everything from a woman’s dress to her education were tightly constricted by moral attitudes that governed her every action. Basically, women were to concentrate their “war efforts” on the task of supporting their husband, brothers, or fathers, in whatever their beliefs were toward the matter. However, as the war dragged on and more men were called into active duty, the farms, factories, stores, and schools were left without workers, so the women stepped up to stand in the gap, as it were. This was most surprising because, back then, women were considered too frail, and their minds too simple for things like politics and war. They were designed for keeping the home and taking care of the babies. Nevertheless, when the men were called into active duty, most of them would have lost their farms, homes, and businesses had it not been for the strength and intelligence of the of the “frail and simple” women. Many women refused to limit their assistance to their country to what could be accomplished close to home. Some of them became nurses, worked to raise supplies for their troops, or even worked in armories, but there was a number of these women decided to support their country in a more dangerous…and scandalous way…they became spies.Back then, espionage was considered a very dishonorable pursuit for a man during the Civil War era, but for a woman…it was tantamount to prostitution. Nevertheless, with the war raging, women of both the North and South flaunted the Victorian morality of the time to provide their country the intelligence it needed to make tactical and practical decisions.

The most famous of these female spies was Belle Boyd…born Marie Isabella Boyd. She began spying for the Confederacy when Union troops invaded her Martinsburg, Virginia home in 1861. One of the Federal soldiers manhandled her mother, and Boyd shot and killed him. She was exonerated in the soldier’s death, and an emboldened Boyd managed to befriend the Union soldiers left to guard her, and used her slave, Eliza, to pass information confided in her by the soldiers along to Confederate officers. Boyd was caught at her first attempt at spying, and threatened with death, but she did not stop her activities. She vowed to find a better way instead. She began eavesdropping on union officers staying at her father’s hotel. She learned enough to inform General Stonewall Jackson about their regiment and activities. Taking no chances, this time, Boyd delivered her intelligence firsthand, moving through Union lines, and reportedly drawing close enough to the action to return with bullet holes in her skirts. The information she provided allowed the Confederate army to advance on Federal troops at Fort Royal. Boyd’s daring acts of espionage soon caught up with her again and when a beau gave her up to Union authorities in 1862, she was arrested and held in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington for a month. Then she released, but found herself in the arrested again soon after. Once again, she managed to be set free, and this time she traveled to England, where amazingly, she married not a Confederate soldier, but a Union officer.

Boyd wasn’t the only spy in the Civil War. Another famous female spy was nicknamed “Crazy Bet,” but her real  name was Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was born to a wealthy and prominent Richmond family, and was educated by Quakers in Philadelphia. When she returned to Richmond, she had become an abolitionist. She even went so far as to convince her mother to free the family’s slaves. Her espionage activity began soon after the start of the war. Her neighbors were appalled, because she openly supported the Union. She concentrated her efforts on aiding Federal prisoners at the Libby Prison, by taking them food, books, and paper. Later, she smuggled information about Confederate activities from the prisoners to Union officers, including General Ulysses S. Grant. To hide her activities from her Confederate neighbors, she behaved oddly. She dressed in old clothes, talking to herself, and refusing to comb her hair. Believe it or not, people began to think she was insane. They started calling her “Crazy Bet.” Van Lew wasn’t insane, in fact, she was incredibly intelligent. She was hailed by Grant as the provider of some of the most important intelligence gathered during the war.

name was Elizabeth Van Lew. Van Lew was born to a wealthy and prominent Richmond family, and was educated by Quakers in Philadelphia. When she returned to Richmond, she had become an abolitionist. She even went so far as to convince her mother to free the family’s slaves. Her espionage activity began soon after the start of the war. Her neighbors were appalled, because she openly supported the Union. She concentrated her efforts on aiding Federal prisoners at the Libby Prison, by taking them food, books, and paper. Later, she smuggled information about Confederate activities from the prisoners to Union officers, including General Ulysses S. Grant. To hide her activities from her Confederate neighbors, she behaved oddly. She dressed in old clothes, talking to herself, and refusing to comb her hair. Believe it or not, people began to think she was insane. They started calling her “Crazy Bet.” Van Lew wasn’t insane, in fact, she was incredibly intelligent. She was hailed by Grant as the provider of some of the most important intelligence gathered during the war.

Captain George Hollins joined the United States Navy when he was just 15 years old, and served during the War of 1812. His was a long and distinguished career, but when the Civil War broke out in 1861, he chose to resign his commission, and offer his services to the Confederacy. After a brief stop in his hometown, Baltimore, Hollins offered his services to the Confederacy and received a commission on June 21, 1861. I suppose that every man had to choose a side in the Civil War, and I’m sure he considered his reasons for choosing the Confederacy to be valid, but many of us would consider his actions to be almost traitorous, were it not for the fact that both sides were the United States…just not so united.

Captain George Hollins joined the United States Navy when he was just 15 years old, and served during the War of 1812. His was a long and distinguished career, but when the Civil War broke out in 1861, he chose to resign his commission, and offer his services to the Confederacy. After a brief stop in his hometown, Baltimore, Hollins offered his services to the Confederacy and received a commission on June 21, 1861. I suppose that every man had to choose a side in the Civil War, and I’m sure he considered his reasons for choosing the Confederacy to be valid, but many of us would consider his actions to be almost traitorous, were it not for the fact that both sides were the United States…just not so united.

Hollins devised a plan to capture a commercial vessel that was bringing supplies to the Union Army. Then they planned to use that ship to lure other Union ships into Confederate service. Soon after, Hollins met up with Richard Thomas Zarvona, a fellow Marylander and former student at West Point. Zarvona  was an adventurer who had fought with pirates in China and revolutionaries in Italy. He seemed the perfect co-conspirator for this project. They devised a plan to capture the Saint Nicholas. Then it would be the decoy they used to force other Yankee ships into Confederate service. Zarvona went to Baltimore,where he recruited a band of pirates, who boarded the Saint Nicholas as paying passengers on June 28, 1862. Using the name Madame La Force, Zarvona disguised himself as a flirtatious French woman. Hollins boarded the Saint Nicholas at its first stop.

was an adventurer who had fought with pirates in China and revolutionaries in Italy. He seemed the perfect co-conspirator for this project. They devised a plan to capture the Saint Nicholas. Then it would be the decoy they used to force other Yankee ships into Confederate service. Zarvona went to Baltimore,where he recruited a band of pirates, who boarded the Saint Nicholas as paying passengers on June 28, 1862. Using the name Madame La Force, Zarvona disguised himself as a flirtatious French woman. Hollins boarded the Saint Nicholas at its first stop.

A while later the band of co-conspirators went to the “French woman’s” cabin. Inside, they armed themselves and came back out on the deck to surprise the crew. After  capturing the crew, Hollins took control of the ship. At this point, the purpose of their mission began. They had planned to capture a Union gunboat, the Pawnee, but it was called away. Instead, the Saint Nicholas and its pirate crew came upon a ship loaded with Brazilian coffee, and two more ships, carrying loads of ice and coal. Both ships quickly fell to the Saint Nicholas. For his actions, Hollins received a promotion to commodore and was sent to New Orleans to command the naval forces there at the end of July. On July 8, he would try another daring mission, to capture the Columbia, a sister ship of the Saint Nicholas, but the captain of the Saint Nicholas was on board the Columbia, on his way home after being released by the Confederate authorities. He recognized the men and they were arrested. It was the end of his tirade.

capturing the crew, Hollins took control of the ship. At this point, the purpose of their mission began. They had planned to capture a Union gunboat, the Pawnee, but it was called away. Instead, the Saint Nicholas and its pirate crew came upon a ship loaded with Brazilian coffee, and two more ships, carrying loads of ice and coal. Both ships quickly fell to the Saint Nicholas. For his actions, Hollins received a promotion to commodore and was sent to New Orleans to command the naval forces there at the end of July. On July 8, he would try another daring mission, to capture the Columbia, a sister ship of the Saint Nicholas, but the captain of the Saint Nicholas was on board the Columbia, on his way home after being released by the Confederate authorities. He recognized the men and they were arrested. It was the end of his tirade.

During the Civil War, rail lines were crucial for moving supplies from one place to another. The different sides often tried to waylay the trains, derail the trains, or even destroy the rails. On June 10, 1864, a Confederate cavalry intercepted General Phillip Sheridan’s Union cavalry while they were trying to destroy a rail line near Trevilian Station, Virginia. The ensuing battle lasted two days before the Confederates were finally able to drive off the Union cavalry from the station, with minimal damage to a precious supply line.

During the Civil War, rail lines were crucial for moving supplies from one place to another. The different sides often tried to waylay the trains, derail the trains, or even destroy the rails. On June 10, 1864, a Confederate cavalry intercepted General Phillip Sheridan’s Union cavalry while they were trying to destroy a rail line near Trevilian Station, Virginia. The ensuing battle lasted two days before the Confederates were finally able to drive off the Union cavalry from the station, with minimal damage to a precious supply line.

After the Confederate victory at the Battle of Cold Harbor in June 1864, in which over 15,000 combined casualties fell during the nearly two-week fight, Union General Ulysses S. Grant dispatched his cavalry commander, General Phillip Sheridan to ride towards Charlottesville and cut the Virginia Central Railroad. The line was supplying Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Lee’s Army was engaged in a life-or-death struggle with Grant’s Army of the Potomac, in the areas of Richmond and Petersburg.

Sheridan turned north to skirt around Richmond and headed toward Charlottesville, which was 60 miles northwest of Richmond. Unfortunately, Sheridan’s move was far from secret, and General Wade Hampton, commander of the Confederate cavalry, set out to intercept the Union cavalry. On the morning of June 11, Union General George Custer’s men attacked Hampton’s supply train near Trevilian Station. Although they scored an initial success, Custer soon found himself almost completely surrounded by the Confederate Cavalry. Custer formed his men into a triangle and made several counterattacks before Sheridan came to his rescue in the late afternoon, taking 500 Southern prisoners in the process.

The struggle continued the next day. With his ammunition running low and his cavalry dangerously far from its supply line, Sheridan eventually withdrew his force and returned to the Army of the Potomac. The Union Cavalry tore up about five miles of rail line, but the damage was relatively light for the high number of casualties. Sheridan lost 735 men compared with nearly 1,000 for Hampton. But the Confederates had driven off the Union cavalry and had kept the damage to railroad to a minimum…not that it would make a difference in the outcome of the Civil War.