Texas

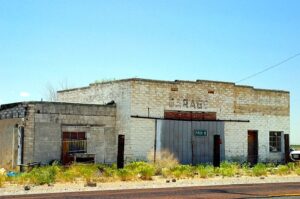

Acala, Texas was once a “thriving” community…well, ok, maybe not exactly thriving, but it the town’s “heydays” it had a population of about 100 people, who made a living raising Acala Cotton. No, it never was big, but the railroad once went through there to take the cotton crop to the market. Acala is located in Hudspeth County, Texas, approximately 34 miles northwest of Sierra Blanca and 54 miles southeast of El Paso on Highway 20. These days the population is approximately 25 people, making Acala more of a ghost town than the unincorporated community that it is technically listed as.

Acala, Texas was once a “thriving” community…well, ok, maybe not exactly thriving, but it the town’s “heydays” it had a population of about 100 people, who made a living raising Acala Cotton. No, it never was big, but the railroad once went through there to take the cotton crop to the market. Acala is located in Hudspeth County, Texas, approximately 34 miles northwest of Sierra Blanca and 54 miles southeast of El Paso on Highway 20. These days the population is approximately 25 people, making Acala more of a ghost town than the unincorporated community that it is technically listed as.

The area was first settled in the early 20th century. In 1917, three farmers combined their resources to plant experimental cotton near Tornillo, about 13 miles northwest of what is now Acala, Texas. Successful the first year, the men purchased more land the next year to grow irrigated cotton. Hearing about the success of these f armers, a man named WT Young came to the area from El Paso to try his hand at cotton farming, but Young would bring much more to the area than cotton. He bought a large piece of cheap desert land near the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks southeast of Tornillo. Using mules to clear the brush and break the soil for the first time, he planted a Mexican variety of cottonseed called Acala. He was so successful that he built his own cotton gin at the site now known as Acala. It wasn’t the first cotton gin, which was built by Eli Whitney, but it was a cotton gin, and it revolutionized Acala.

armers, a man named WT Young came to the area from El Paso to try his hand at cotton farming, but Young would bring much more to the area than cotton. He bought a large piece of cheap desert land near the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks southeast of Tornillo. Using mules to clear the brush and break the soil for the first time, he planted a Mexican variety of cottonseed called Acala. He was so successful that he built his own cotton gin at the site now known as Acala. It wasn’t the first cotton gin, which was built by Eli Whitney, but it was a cotton gin, and it revolutionized Acala.

The town began to grow, and a post office was established in 1925. It was operated by Mrs Julia Vaughn. By 1929, the population had doubled from 50 people to its peak of 100 people. The population varied over the years, peaking again in the late 1950s, at 100 people. Unfortunately, the town could not maintain the population, and soon declined, once again. By the 1970’s there were about 25 people. Since then, it has remained at that size. Acala is in the Fort Hancock Independent School District. Fort Hancock High School is the district’s comprehensive high school.

The United States Census Bureau first listed Acala as a census-designated place prior to the 2020 census. A

census-designated place (CDP) is a statistical geography representing closely settled, unincorporated communities that are locally recognized and identified by name. The designation doesn’t necessarily add any importance or value to the town, however. Nevertheless, the fact that it was at one time a successful agricultural area and operated a successful cotton gin, gives it definite historical value.

census-designated place (CDP) is a statistical geography representing closely settled, unincorporated communities that are locally recognized and identified by name. The designation doesn’t necessarily add any importance or value to the town, however. Nevertheless, the fact that it was at one time a successful agricultural area and operated a successful cotton gin, gives it definite historical value.

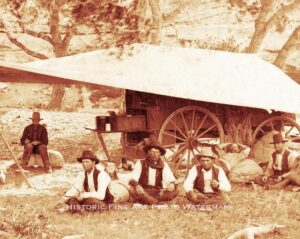

After watching numerous old western shows about cattle drives, most of us would automatically assume that a chuckwagon is a staple on any cattle drive. That is not the case, however. In the early years of cattle drives, the cowboys were supposed to supply their own food, and had to survive on what they could forage and carry. With that in mind, hiring cowboys for the drive was tough. Cowboys were usually paid about $25 to $40 a month, so to have to buy food out of that too, doesn’t make cattle driving a “get rich quick” kind of job. Basically, cattle ranchers ended up with people who couldn’t get a job anywhere else, and they usually weren’t loyal or very good at their job. They might even walk off the job before the drive was over.

After watching numerous old western shows about cattle drives, most of us would automatically assume that a chuckwagon is a staple on any cattle drive. That is not the case, however. In the early years of cattle drives, the cowboys were supposed to supply their own food, and had to survive on what they could forage and carry. With that in mind, hiring cowboys for the drive was tough. Cowboys were usually paid about $25 to $40 a month, so to have to buy food out of that too, doesn’t make cattle driving a “get rich quick” kind of job. Basically, cattle ranchers ended up with people who couldn’t get a job anywhere else, and they usually weren’t loyal or very good at their job. They might even walk off the job before the drive was over.

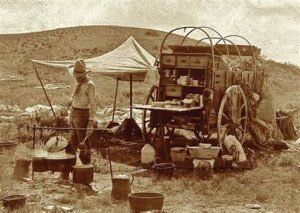

It was a big problem for ranchers, who needed to have reliable, as well as capable cowboys to work the drives. Finally, one rancher, a man named Charles Goodnight, while pondering the problem he had in getting good working cowboys for his cattle drive. Then, he hit upon an idea. Goodnight created a type of field kitchen covered wagon. It is unknown if the name comes from the fact that the inventor is Charles (Chuck) or if it referenced chuck as a slang term for food. “Goodnight modified a Studebaker-manufactured covered wagon, a d urable Civil War army-surplus wagon, to suit the needs of cowboys driving cattle from Texas to sell in New Mexico. He added a ‘chuck box’ to the back of the wagon, with drawers and shelves for storage space and a hinged lid to provide a flat working surface. A water barrel was also attached to the wagon and canvas was hung underneath to carry firewood. A wagon box was used to store cooking supplies and cowboys’ personal items.” It is said that Goodnight’s main motivation for the chuckwagon, was to be able to hire a better class of cowboy and keep them throughout the cattle drive.

urable Civil War army-surplus wagon, to suit the needs of cowboys driving cattle from Texas to sell in New Mexico. He added a ‘chuck box’ to the back of the wagon, with drawers and shelves for storage space and a hinged lid to provide a flat working surface. A water barrel was also attached to the wagon and canvas was hung underneath to carry firewood. A wagon box was used to store cooking supplies and cowboys’ personal items.” It is said that Goodnight’s main motivation for the chuckwagon, was to be able to hire a better class of cowboy and keep them throughout the cattle drive.

“Chuckwagon food typically included easy-to-preserve items such as baked beans, salted meats, coffee, and sourdough biscuits. Food would also be gathered en route. There was no fresh fruit, vegetables, or eggs available, and meat was not fresh unless an animal was injured during the run and therefore had to be killed. The meat they ate was greasy cloth-wrapped bacon, salt pork, and beef, usually dried, salted or smoked. On cattle drives, it was common for the “cookie” who ran the wagon to be second in authority only to the “trailboss.” The cookie would often act as cook, barber, dentist, and banker.” A typical trail boss made $100 to $125 a month, and the cook usually made about $60.  The cook was vital to the cattle drive and was not to be crossed. The men were to keep their distance from the chuckwagon, because dust would get in the food. The horses left camp downwind of the chuckwagon for the same reason. No one dared take the last serving of food until they were sure that everyone had been served. To leave food on their plates was an insult to the cook. The cooks had long days…up before dawn to prepare food. After the men left for work, they cleaned up camp and washed dishes, then went to the next camp site to begin dinner for the men’s arrival. After dinner they cleaned up and went to bed. The next day would soon arrive. They more than earned their wage and the special wagon they got to use.

The cook was vital to the cattle drive and was not to be crossed. The men were to keep their distance from the chuckwagon, because dust would get in the food. The horses left camp downwind of the chuckwagon for the same reason. No one dared take the last serving of food until they were sure that everyone had been served. To leave food on their plates was an insult to the cook. The cooks had long days…up before dawn to prepare food. After the men left for work, they cleaned up camp and washed dishes, then went to the next camp site to begin dinner for the men’s arrival. After dinner they cleaned up and went to bed. The next day would soon arrive. They more than earned their wage and the special wagon they got to use.

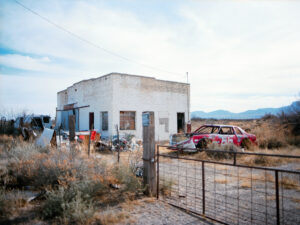

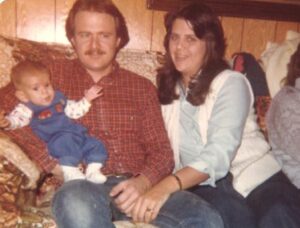

My husband, Bob’s uncle, Eddie Hein was a sweet man who was an encouragement to many people. His children were his pride and joy, and he would do anything in his power to make their lives better. When Larry wanted to open a mechanics shop, Eddie was totally onboard. Eddie always loved mechanics, and seeing Larry start a career in that field was pleasing to him. Eddie loved vintage cars and would have loved to spend hours working to restore them. Of course, that wasn’t feasible, so watching his same work on cars sometimes filled the mechanics gap, in his life…at least the one that existed in his latter years.

My husband, Bob’s uncle, Eddie Hein was a sweet man who was an encouragement to many people. His children were his pride and joy, and he would do anything in his power to make their lives better. When Larry wanted to open a mechanics shop, Eddie was totally onboard. Eddie always loved mechanics, and seeing Larry start a career in that field was pleasing to him. Eddie loved vintage cars and would have loved to spend hours working to restore them. Of course, that wasn’t feasible, so watching his same work on cars sometimes filled the mechanics gap, in his life…at least the one that existed in his latter years.

His daughter, Kim Arani had very different goals and dreams than her dad, which makes sense. Most women don’t dream of becoming a mechanic. Kim chose later to move to Texas, because she absolutely hates the Montana winters, and I can’t say as I blame her. Even though Kim lived far away know, Eddie and Pearl were very supportive of her dreams, and were very excited to attend her wedding and give the bride away. It was a dream wedding, and while Eddie had suffered a stroke prior to the wedding, he was able to make the trip and walk his daughter down the aisle…on the beach.

While Eddie was dedicated to his children, Larry and Kim, he was most dedicated to his loving wife, Pearl. When they were off work, they were together. They gardened together and worked on the house together. Their lives

were intertwined. When Eddie had his stroke, Pearl really stepped up to make sure Eddie had everything he needed. She drove him lots of miles to do his therapy. She took care of him at home. She nursed him back to health, and Eddie was grateful. He knew he loved her from the very start, and she proved to be the best thing that ever happened to him. Today would have been Eddie’s 80th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Eddie!! We love and miss you very much!!

were intertwined. When Eddie had his stroke, Pearl really stepped up to make sure Eddie had everything he needed. She drove him lots of miles to do his therapy. She took care of him at home. She nursed him back to health, and Eddie was grateful. He knew he loved her from the very start, and she proved to be the best thing that ever happened to him. Today would have been Eddie’s 80th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Eddie!! We love and miss you very much!!

Years ago, when natural gas was first being used for energy, it had no odor, and so, if there was a leak, there was no warning. Natural gas was considered safe, and for the most part, it was, but when it leaked, and fumes pooled, any spark could be deadly. There is another kind of natural gas, called wet-gas that is less stable that natural gas, and probably should never have been used, but in the 1930s, the dangers were less known. Natural gas was more expensive, so sometimes consumers…mostly large consumers opted for the cheaper wet-gas to save a little money.

Years ago, when natural gas was first being used for energy, it had no odor, and so, if there was a leak, there was no warning. Natural gas was considered safe, and for the most part, it was, but when it leaked, and fumes pooled, any spark could be deadly. There is another kind of natural gas, called wet-gas that is less stable that natural gas, and probably should never have been used, but in the 1930s, the dangers were less known. Natural gas was more expensive, so sometimes consumers…mostly large consumers opted for the cheaper wet-gas to save a little money.

The Consolidated School of New London, Texas actually sat in the middle of a large oil and natural gas field. Texas is known for its oil and natural gas fields, and it wasn’t uncommon for towns to be build right in the middle of the fields. The area of New London was dominated by 10,000 oil derricks, 11 of which stood right on school grounds. The school, costing close to $1 million, was newly built in the 1930s and, from its inception, it bought natural gas from Union Gas to supply its energy needs. The school’s monthly natural gas bill averaged about $300 a month, and with such an exorbitant bill, the school officials were eventually persuaded to save money by switching over to the wet-gas lines, which were operated by Parade Oil Company. The lines ran near the school, and the cost to use them was definitely less. Wet-gas is a type of waste gas that has more impurities than typical natural gas and wasn’t as safe. Still, at the time, it wasn’t uncommon for consumers living near oil fields to use this gas.

On March 18, 1937, at approximately 3:05pm, a Thursday afternoon, school was about to end for the day, and  the 694 students and 40 teachers at the Consolidated School were waiting for the final bell, which was to ring in 10 minutes. It was not the final bell that was heard, but rather a huge explosion and powerful explosion shook the region. The blast literally blew the roof off of the building, leveled the school. There was no warning, because back then, natural gas was odorless. Nevertheless, in the presence of the leaking fumes, a single spark…or even static electricity, had the ability to create an explosion of indescribable proportions…and that is exactly what happened. When the blast came, it could be felt 40 miles away and most of the victims were killed instantly. From all over town, and even the surrounding towns, rescue workers and even everyday citizens rushed to the scene to pull out survivors. Surprisingly, hundreds of injured students were hauled from the rubble, and some students miraculously walked away unharmed. Ten students were found under a large bookcase that, when it fell, actually shielded them from the falling building. The rescue workers quickly established first-aid stations in the nearby towns of Tyler, Overton, Kilgore, and Henderson to tend to the wounded. It was noted that a blackboard at the destroyed school was found that read, “Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest natural gifts. Without them, this school would not be here and none of us would be learning our lessons.” Yes, they were, but they could also be the greatest danger.

the 694 students and 40 teachers at the Consolidated School were waiting for the final bell, which was to ring in 10 minutes. It was not the final bell that was heard, but rather a huge explosion and powerful explosion shook the region. The blast literally blew the roof off of the building, leveled the school. There was no warning, because back then, natural gas was odorless. Nevertheless, in the presence of the leaking fumes, a single spark…or even static electricity, had the ability to create an explosion of indescribable proportions…and that is exactly what happened. When the blast came, it could be felt 40 miles away and most of the victims were killed instantly. From all over town, and even the surrounding towns, rescue workers and even everyday citizens rushed to the scene to pull out survivors. Surprisingly, hundreds of injured students were hauled from the rubble, and some students miraculously walked away unharmed. Ten students were found under a large bookcase that, when it fell, actually shielded them from the falling building. The rescue workers quickly established first-aid stations in the nearby towns of Tyler, Overton, Kilgore, and Henderson to tend to the wounded. It was noted that a blackboard at the destroyed school was found that read, “Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest natural gifts. Without them, this school would not be here and none of us would be learning our lessons.” Yes, they were, but they could also be the greatest danger.

The investigators were never able to determine the exact cause of the spark that ignited the gas, noting that it very well may have been simple static electricity. Sadly, the dangers of wet-gas came more to light because of this incident, and as a result wet gas was required to be burned at the site rather than piped away. Also, as a safety precaution, a new state law was put into place, mandating the usage of malodorants in natural gas for  commercial and industrial use. This would provide a warning to anyone in the area of a natural gas leak, and hopefully prevent large casualties such as the ones felt in this explosion. The number of people estimated killed in the explosion is 294, but the actual number of victims remains unknown. The majority were from grades five through eleven, because the younger students were educated in a separate building, and most of them had already been dismissed from school. Many of the victims were only identified by their clothing or fingerprints, which was only available because many inhabitants of the surrounding area had been fingerprinted at the Texas Centennial Exposition the previous summer. Who could have known the importance of that exposition?

commercial and industrial use. This would provide a warning to anyone in the area of a natural gas leak, and hopefully prevent large casualties such as the ones felt in this explosion. The number of people estimated killed in the explosion is 294, but the actual number of victims remains unknown. The majority were from grades five through eleven, because the younger students were educated in a separate building, and most of them had already been dismissed from school. Many of the victims were only identified by their clothing or fingerprints, which was only available because many inhabitants of the surrounding area had been fingerprinted at the Texas Centennial Exposition the previous summer. Who could have known the importance of that exposition?

No one wants to think about an innocent person going to prison for a crime they did not commit, and I like to think that it doesn’t happen very often, but I think there was a time when it was a little more common that it is these days. While it may not happen as often these days as it used to, more and more of these wrongful incarcerations are coming to light these days, because of DNA testing. Michael Morton (born August 12, 1954) was convicted in a Williamson County, Texas court in 1986, of murdering his wife, Christine Morton. He never gave up the fight. He maintained in innocence until the end, and in the end, it was proven that he was in fact, innocent. Unfortunately, that did not mean that he was spared a prison sentence. He actually spent almost 25 years behind bars, sadly.

No one wants to think about an innocent person going to prison for a crime they did not commit, and I like to think that it doesn’t happen very often, but I think there was a time when it was a little more common that it is these days. While it may not happen as often these days as it used to, more and more of these wrongful incarcerations are coming to light these days, because of DNA testing. Michael Morton (born August 12, 1954) was convicted in a Williamson County, Texas court in 1986, of murdering his wife, Christine Morton. He never gave up the fight. He maintained in innocence until the end, and in the end, it was proven that he was in fact, innocent. Unfortunately, that did not mean that he was spared a prison sentence. He actually spent almost 25 years behind bars, sadly.

On the afternoon of August 13, 1986, a neighbor found 31-year-old Christine Morton beaten to death in her bed in the Williamson County, Texas, home near Austin, that she shared with Michael, a grocery store manager, and their 3-year-old son, Eric. The investigation began, and six weeks later, Morton, who had no criminal record or history of violence, was arrested for Christine’s murder. At trial, the prosecution contended Morton had slain his wife of seven years after she refused to have sex with him on the night of August 12, his 32nd birthday. Morton stated repeatedly that he had nothing to do with his wife’s death and said an intruder must have killed her after he left for work early on the morning of August 13. No witnesses or physical evidence linked Morton to the crime. There wasn’t anything circumstantial or ever really anything alleged to connect him to the crime, except that he had access to the home. Nevertheless, Michael Morton was convicted on February 17, 1987, and sentenced to life behind bars. So began his nightmare.

During his trial and subsequent time in prison, Morton’s defense team asked the state to test DNA on a variety of items, including a blood-stained bandanna found by police the day after the murder at an abandoned construction site close to the Morton home. For whatever reason, the Williamson County district attorney successfully blocked all requests for testing until 2010, when a Texas appeals court ordered that testing on the bandana take place. The team’s persistence finally paid off. The test results revealed the bandana contained Christine Morton’s blood and hair, along with the DNA of another man, Mark Alan Norwood, who was a felon with a long criminal record. Norwood had worked in the Austin area as a carpet layer at the time of the murder.

Finally, after waiting almost 25 years for real justice, Michael Morton was released on October 4, 2011. A month after Morton was freed, Norwood, who was by then 57, was arrested for Christine Morton’s killing. In March 2013, he was found guilty of her murder and sentenced to life in prison. Based on DNA evidence, Norwood also was indicted for killing a second woman, Debra Baker, whose 1988 murder in Austin had remained unsolved. Like Morton, Baker was bludgeoned to death in her bed. She lived just blocks from Norwood at the time of her murder. Michael Morton was officially exonerated in December of that year.

After a yearlong investigation into prosecutor, Ken Anderson, the State Bar of Texas filed a disciplinary petition against Ken Anderson in October 2012. By then, the prosecutor was a Texas district, elected in 2002. The Texas State Bar alleged that Anderson had withheld various pieces of evidence from Morton’s attorneys, including a transcript of an August 1986 taped interview between the case’s lead investigator and Morton’s mother-in-law, in which she stated that Morton’s then 3-year-old son, Eric had told her in detail about witnessing his mother’s murder and said his father was not home at the time. Anderson managed to pull off a plea deal to settle the charges against him. He agreed to serve 10 days in jail, perform 500 hours of community service, give up his law license and pay a $500 fine. I think that is an outrageous miscarriage of justice. He had knowingly withheld evidence that cost another man 25 years of his life. He should have had to serve the same length of time.

Morton was later able to re-establish contact with his son, who had cut ties with him when he was fifteen, because he then believed that he had not remembered the incident correctly, and it was his dad who had killed

his mom. A further miscarriage of justice that was handed down to the elder Morton. He had not only lost 25 years of his own life, but an additional 13 years of his son’s life. Thankfully, Christine Morton’s sister adopted Eric Morton, so his dad was able to find his son when he got out of prison. When his was released, Morton lived with his parents in Liberty City, Texas for a while, before moving to Kilgore, Texas. In 2013, Morton married Cynthia May Chessman, who he met at his church.

his mom. A further miscarriage of justice that was handed down to the elder Morton. He had not only lost 25 years of his own life, but an additional 13 years of his son’s life. Thankfully, Christine Morton’s sister adopted Eric Morton, so his dad was able to find his son when he got out of prison. When his was released, Morton lived with his parents in Liberty City, Texas for a while, before moving to Kilgore, Texas. In 2013, Morton married Cynthia May Chessman, who he met at his church.

After losing both her husband, our Uncle Eddie Hein and her son, our cousin Larry Hein, within three months of each other, Aunt Pearl Hein went through some very sad and difficult times. That much loss can be devastating to a person. It was very hard on Pearl, but she is starting to live life again. I know that Eddie and Larry would be glad that she is. Pearl was very much loved by both of her men, as was her daughter Kim Arani. While it’s been hard to go forward, Pearl has been making great strides with the help of her daughter and son-in-law, Michael Arani. She has made a couple of trips to Texas, to visit them, and the warm climate, as well as the beautiful scenery have soothed her soul. Of course, it doesn’t really lessen the pain of the loss, but it is a matter of learning to live again.

After losing both her husband, our Uncle Eddie Hein and her son, our cousin Larry Hein, within three months of each other, Aunt Pearl Hein went through some very sad and difficult times. That much loss can be devastating to a person. It was very hard on Pearl, but she is starting to live life again. I know that Eddie and Larry would be glad that she is. Pearl was very much loved by both of her men, as was her daughter Kim Arani. While it’s been hard to go forward, Pearl has been making great strides with the help of her daughter and son-in-law, Michael Arani. She has made a couple of trips to Texas, to visit them, and the warm climate, as well as the beautiful scenery have soothed her soul. Of course, it doesn’t really lessen the pain of the loss, but it is a matter of learning to live again.

Sometimes, the heart needs a change of scenery to help with healing, and when Pearl was in Texas visiting Kim and Michael, they took a trip down to Rosemary Beach, Florida, where they stayed at a hotel called “The Pearl,” otherwise known as their happy place. How perfect to find such a hotel with Pearl’s name. That and the peaceful time spent on the beach was sure to warm her heart and was a welcome change from the end of October cold weather that is Forsyth, Montana, where Pearl lives.

Pearl has always been a hard-working woman. She took care of her parents, and later her husband, Eddie

when they really needed her help. Caregiving is a big job, and having done it myself, I totally commend anyone who willingly steps into that role. It is truly a life changing undertaking. You sacrifice most of your life on a daily basis, and while many would think that it is a thankless job, it most definitely is one of the hardest and most rewarding jobs you will ever undertake. Whether the words “thank you” are ever said or not, and believe me they always are, you feel the “thank you” that comes from their hearts every time you are with them. No words can ever really express their gratitude. All they can do is hope you can see the appreciation in their eyes and know that it comes from their hearts…and believe me, you can. Today is Pearl’s birthday. Happy birthday Pearl!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

when they really needed her help. Caregiving is a big job, and having done it myself, I totally commend anyone who willingly steps into that role. It is truly a life changing undertaking. You sacrifice most of your life on a daily basis, and while many would think that it is a thankless job, it most definitely is one of the hardest and most rewarding jobs you will ever undertake. Whether the words “thank you” are ever said or not, and believe me they always are, you feel the “thank you” that comes from their hearts every time you are with them. No words can ever really express their gratitude. All they can do is hope you can see the appreciation in their eyes and know that it comes from their hearts…and believe me, you can. Today is Pearl’s birthday. Happy birthday Pearl!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Tornadoes can happen anywhere, but there are areas of the country that are more prone to tornadoes. Nevertheless, the F-5 tornado is extremely rare, and thankfully so, but when one hits a town, it is…devastating!! On May 27, 1997, an F-5 tornado his Jarrell, Texas, killing 27 people and destroying dozens of homes. That damage and loss of life was horrific, but it was what happened afterward that was truly amazing.

Tornadoes can happen anywhere, but there are areas of the country that are more prone to tornadoes. Nevertheless, the F-5 tornado is extremely rare, and thankfully so, but when one hits a town, it is…devastating!! On May 27, 1997, an F-5 tornado his Jarrell, Texas, killing 27 people and destroying dozens of homes. That damage and loss of life was horrific, but it was what happened afterward that was truly amazing.

Once the news of the devastating tornado broke, people from near and far started showing up to do whatever it took to help out. In fact, people showed up by the busloads. The people were there to help with the cleanup, but that wasn’t really all they were there for. Upon arrival, they found that there was a great need for blood, because many who were critically injured needed blood and without a second thought, they showed up at blood banks and hospitals, ready to donate the critical blood that was needed. Besides giving blood, volunteers helped pick up debris and rubble. The work was hard, but those who arrived in Jarrell wanted to show their support to the residents of the devastated town.

The town of Jarrell, population around 400 at the time of the tornado lost entire families, like the Igo family of five, the Moehring family of four, the Smith family of three, and the Gower family of 2. but since the tornado, the town has really been growing. These days, Jarrell has more than 1750 people in residence. Really, that goes to show that these people were not going to give up. They were going to rebuild their lives and their town. Twenty-five years can make a huge difference in a town’s history. People can forget what happened so long ago, but if the survivors never forget, they can pass the history of the tragedy on to the future generations.

I’m sure that over the years, there were those who couldn’t bear to stay there any longer. That happens too. Not everyone is able to move on from the past, and sometimes people just don’t want to stay where there has been so much loss. There is really no right or wrong thing to do, it is simply what the people who went through

the tragedy need to do in order to heal. As for the town, it has been rebuilt and it is growing all the time. I think that Jarrell will thrive again, and maybe even become a larger city in time. The fact that the town has the ability to heal and move on is due in large part to the help of the amazing people came to the rescue 25 years ago in Jarrell’s hour of need.

the tragedy need to do in order to heal. As for the town, it has been rebuilt and it is growing all the time. I think that Jarrell will thrive again, and maybe even become a larger city in time. The fact that the town has the ability to heal and move on is due in large part to the help of the amazing people came to the rescue 25 years ago in Jarrell’s hour of need.

Charles Angelo “Charlie” Siringo didn’t set out to be a lawman, a detective, or a bounty hunter, but the circumstances of his life put him in places where things just fell into place to bring his future into being. Born on February 7, 1855, on the Matagorda Peninsula in Matagorda County, Texas. His mother was an Irish immigrant, and his father was an Italian immigrant from Piedmont. His father died when Siringo was a year old. Siringo attended public school until the start of the American Civil War. In 1867, when he was just 12 years old, Siringo took his first cowpuncher lessons, before moving to Saint Louis after his mother remarried.

Charles Angelo “Charlie” Siringo didn’t set out to be a lawman, a detective, or a bounty hunter, but the circumstances of his life put him in places where things just fell into place to bring his future into being. Born on February 7, 1855, on the Matagorda Peninsula in Matagorda County, Texas. His mother was an Irish immigrant, and his father was an Italian immigrant from Piedmont. His father died when Siringo was a year old. Siringo attended public school until the start of the American Civil War. In 1867, when he was just 12 years old, Siringo took his first cowpuncher lessons, before moving to Saint Louis after his mother remarried.

Siringo attended Fisk public school for a while in New Orleans, but school wasn’t really of interest to him, so he started work as a cowboy for Abel Head “Shanghai” Pierce in April 1871, after returning to Texas. He was just 16 years old, and yet he had done more in his short lifetime that most people would have dreamed of doing. And yet, that was just the beginning. In July 1877, Siringo was in Dodge City, Kansas, where he survived an encounter with Bat Masterson.

Then, Siringo started working for the LX Ranch working as a cattle drive cowboy. This was an unusual kind of cattle drive job, in that it also entailed chasing after LX cattle stolen by Billy the Kid in 1880. By 1884, Siringo  was married Mamie and he quit working for LX Ranch. He opened a tobacco store in Caldwell, Kansas. He and Mamie had a daughter named Viola, born on February 28, 1885. At this point, it seemed prudent to find a safer kind of work, so he began writing his autobiography, “A Texas Cow Boy; Or Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony.” A year later, it was published and well received. Siringo moved his family to Chicago in the spring of 1886 for publication of a second printing.

was married Mamie and he quit working for LX Ranch. He opened a tobacco store in Caldwell, Kansas. He and Mamie had a daughter named Viola, born on February 28, 1885. At this point, it seemed prudent to find a safer kind of work, so he began writing his autobiography, “A Texas Cow Boy; Or Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony.” A year later, it was published and well received. Siringo moved his family to Chicago in the spring of 1886 for publication of a second printing.

In 1886, Siringo witnessed the Chicago Haymarket affair. “The Haymarket affair (also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, or the Haymarket Square riot) was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It began as a peaceful rally in support of workers striking for an eight-hour workday, the day after police killed one and injured several workers. An unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at the police as they acted to disperse the meeting, and the bomb blast and ensuing gunfire caused the deaths of seven police officers and at least four civilians; dozens of others were wounded.”

Seeing all that destruction prompted Siringo to join the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. He used gunman Pat Garrett’s name as a reference to get the job, having met Garrett in 1880, when they were searching for Billy the Kid. Siringo was hired immediately, and assigned to Denver, reporting to James McParland. He moved his family to Denver, where his wife died in 1890, leaving him with his young daughter to raise. Eventually she went to live with his wife’s aunt and her husband, Emma and Will F Read. Siringo was then assigned several  cases, which took him as far north as Alaska, for the Treadwell mine, and as far south as Mexico City. Using a relatively new technique at the time, he began operating under cover as Charles L Carter and infiltrated gangs of robbers and rustlers, making more than 100 arrests.

cases, which took him as far north as Alaska, for the Treadwell mine, and as far south as Mexico City. Using a relatively new technique at the time, he began operating under cover as Charles L Carter and infiltrated gangs of robbers and rustlers, making more than 100 arrests.

Siringo had a difficult married life, following his first wife’s death. It makes you wonder if he would have stayed married, had she lived. A second marriage in 1893 to Lillie Thomas ended in divorce after three years. They had a son named William Lee Roy. After the divorce, Lillie took their son and moved to Los Angeles. Two other marriages, one in 1907 to a woman named Grace and one in 1913 to a woman named Ellen Partain. Each of these lasted only a few months. Finally, Siringo moved to California to be closer to his children. In the end, it wasn’t his cowboy years or his detective years that really made Siringo famous, but rather his writing. Siringo was the author of seven books. Siringo died on October 28, 1928, in Altadena, California.

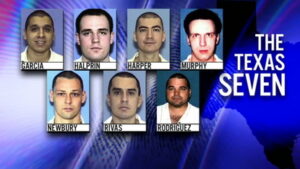

Maybe they were just wanting to be home for Christmas, and not knowing exactly how long it would take…while hiding out from the law, that is…the Texas Seven decided to get a jump start on the journey. No, probably not. It wasn’t Christmas with loved ones that was on their minds…it was freedom. On December 13, 2000, seven prisoners dubbed the “Texas Seven” by the media, broke out of maximum-security prison in South Texas, setting off a massive six-week manhunt. The prisoners were Joseph Christopher Garcia, Randy Ethan Halprin, Larry James Harper, Patrick Henry Murphy Jr, Donald Keith Newbury, George Angel Rivas Jr, and Michael Anthony Rodriguez. The escapees overpowered civilian employees and prison guards in the maintenance shop where they worked and stole clothing, guns, and a vehicle. The men left a note saying: “You haven’t heard the last of us yet,” and they were right. These men were convicted of crimes like murder, rape, and robbery. They were set to be executed soon, so they had nothing to lose.

Maybe they were just wanting to be home for Christmas, and not knowing exactly how long it would take…while hiding out from the law, that is…the Texas Seven decided to get a jump start on the journey. No, probably not. It wasn’t Christmas with loved ones that was on their minds…it was freedom. On December 13, 2000, seven prisoners dubbed the “Texas Seven” by the media, broke out of maximum-security prison in South Texas, setting off a massive six-week manhunt. The prisoners were Joseph Christopher Garcia, Randy Ethan Halprin, Larry James Harper, Patrick Henry Murphy Jr, Donald Keith Newbury, George Angel Rivas Jr, and Michael Anthony Rodriguez. The escapees overpowered civilian employees and prison guards in the maintenance shop where they worked and stole clothing, guns, and a vehicle. The men left a note saying: “You haven’t heard the last of us yet,” and they were right. These men were convicted of crimes like murder, rape, and robbery. They were set to be executed soon, so they had nothing to lose.

These were not the kind of people that anyone wanted to have running around the state…or anywhere outside of prison walls. Soon after escaping from the Connally Unit lockup in Kenedy, Texas, the fugitives picked up another getaway vehicle. This one provided by the father of one of the men. They robbed a Radio Shack store in Pearland, Texas, coming out with cash and police scanners. On Christmas Eve, the escapees struck a sporting-goods store in Irving, Texas, where they stole a large amount of cash and weapons. In the process, the men killed police officer Aubrey Hawkins, shooting him multiple times with multiple weapons and running him over. Now they really had nothing to lose. Now, they were cop killers on top of everything else. It looked like it was time to get out of Dodge…or in this case, Texas.

The Texas Seven headed to Colorado, where they purchased a motor home and told people they were Christian missionaries. They rented a spot at a trailer park near Woodland Park, Colorado. They were there about a month before things started to fall apart. On January 22, 2001, after seeing the “Texas Seven” profiled on the TV program America’s Most Wanted, someone tipped off the police to the group of seven “missionaries” near Woodland Park. During the raid, ringleader George Rivas was captured along with three of the other men. Larry James Harper decided that he was not going back to prison, so he committed suicide after being surrounded by  police. Two days later, law enforcement officials closed in on the two remaining escapees at a hotel in Colorado Springs. A standoff ensued, during which the fugitives conducted phone interviews with a TV news station and claimed their escape was a protest against Texas’ criminal justice system. Someone always has to add a bit of drama to justify their new crimes. There was no evidence indicating their claim was justified. The men then surrendered to authorities. Their crime spree was over. Of the six remaining, four have since been executed. Randy Ethan Halprin and Patrick Henry Murphy Jr are currently back at Polunsky Unit in Livingston, Texas on Death Row awaiting execution.

police. Two days later, law enforcement officials closed in on the two remaining escapees at a hotel in Colorado Springs. A standoff ensued, during which the fugitives conducted phone interviews with a TV news station and claimed their escape was a protest against Texas’ criminal justice system. Someone always has to add a bit of drama to justify their new crimes. There was no evidence indicating their claim was justified. The men then surrendered to authorities. Their crime spree was over. Of the six remaining, four have since been executed. Randy Ethan Halprin and Patrick Henry Murphy Jr are currently back at Polunsky Unit in Livingston, Texas on Death Row awaiting execution.

Life isn’t always easy, and it doesn’t always go the way we thought it would go. Even spending many good years together, doesn’t guaranty that we will have many more. For Pearl Hein, who loved her husband Eddie Hein so much, the end came far too soon, but in a loving marriage, the end always comes too soon. No matter how many years you have been together. Then, it is up to the one left behind, to go forward, because their spouse would want them to continue living. Such was the case with Eddie. He wanted Pearl to live on.

Life isn’t always easy, and it doesn’t always go the way we thought it would go. Even spending many good years together, doesn’t guaranty that we will have many more. For Pearl Hein, who loved her husband Eddie Hein so much, the end came far too soon, but in a loving marriage, the end always comes too soon. No matter how many years you have been together. Then, it is up to the one left behind, to go forward, because their spouse would want them to continue living. Such was the case with Eddie. He wanted Pearl to live on.

Since Eddie’s passing, Pearl has done a little traveling. With her daughter, Kim Arani and her husband, Michael living in Texas, Pearl has become a bit of a traveler…maybe not a world traveler, but a traveler nevertheless. I have been very happy that Pearl is spending time with Kim and Michael in Texas and their place in Florida. She really needed the time away from the cold weather in Forsyth, Montana where she lives, and after losing her son, Kim’s brother, Larry Hein too…just three months after his dad, things have been very sad for Pearl over the past

I know she had a lovely time visiting Kim and Michael, and I am so happy for them all. They needed The time together so they could begin to heal. One of the best ways to heal after a loss is to take the time to share the memories of the past. I’m sure Kim and Pearl did a lot of reminiscing during Pearl’s visit, and I’m sure it was a great healing process. I know that Eddie and Larry would both be very glad Pearl went to Texas. I know it was hard for her to move on alone, but it is what they would want her to do.

I remember watching the newer version of “Titanic” and when Rose survives the sinking, she goes on to live a full life, because Jack told her to live on. Life after loss is never easy, but it can be rewarding. People are meant to survive and to thrive. We are wired to grieve and to move forward with our lives. That doesn’t mean that it is an easy thing to do, but it is a necessary thing to do. I’m glad to see that Pearl is making that transition. Today is Aunt Pearl’s birthday. Happy birthday Pearl!! Have a great day!! We love you!!