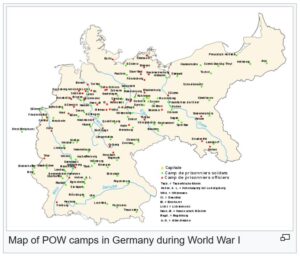

magdeburg

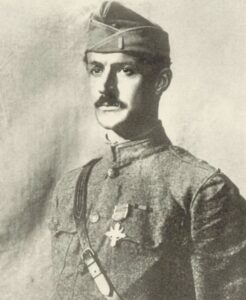

World War I was a different era, even in the way war was conducted. Oh, war is still war, and there is wounding, bombing, killing, and capturing. Nevertheless, with one leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II, there was also compassion. After being captured and placed in a POW camp, a British officer, Captain Robert Campbell found out that his mother was dying. He couldn’t bear the thought of not seeing his mother before she passed away, and in his grief, he took a chance. He appealed to Kaiser Wilhelm II, asking to be allowed to go home to visit his mother before she died. Amazingly, Kaiser Wilhelm II granted his request, on the condition that he return to the POW camp after the visit.

World War I was a different era, even in the way war was conducted. Oh, war is still war, and there is wounding, bombing, killing, and capturing. Nevertheless, with one leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II, there was also compassion. After being captured and placed in a POW camp, a British officer, Captain Robert Campbell found out that his mother was dying. He couldn’t bear the thought of not seeing his mother before she passed away, and in his grief, he took a chance. He appealed to Kaiser Wilhelm II, asking to be allowed to go home to visit his mother before she died. Amazingly, Kaiser Wilhelm II granted his request, on the condition that he return to the POW camp after the visit.

When you think about it, once he was safely home with his mother, Captain Campbell could have simply stayed. Seriously, what could the Kaiser have done about it. Nevertheless, being an honorable man, Captain Campbell kept his promise to Kaiser Wilhelm II and returned from Kent to Germany after visiting his mother for a week. He stayed at the camp until the war ended in 1918. That was not the end of the story, however.

On August 24, 1914, then 29-year-old Captain Campbell, of the 1st Battalion East Surrey Regiment, was captured in northern France. He was sent to a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp in Magdeburg, north-east Germany. It was there that he received the heartbreaking news that his mother, Louise was dying of cancer. Captain Campbell traveled through the Netherlands and then by boat and train to Gravesend in Kent, where he spent a week with his mother before returning to Germany the same way. His mother died in February 1917.

With the kindness of the Kaiser, and a duty to honor his word, Captain Campbell, knowing that if he didn’t return, no one else would ever be given that same consideration, Captain Campbell returned to Germany. Strangely, there was no issues during his return. I suppose the Kaiser could have cleared the way previously, but it would be my guess that the Kaiser was just as shocked by the return as I am. Unfortunately, Britain wasn’t as considerate, because they blocked a similar request from German prisoner Peter Gastreich, who was being held at an internment camp on the Isle of Man. After that no other British prisoners of war were afforded compassionate leave.

As for Captain Campbell, while he felt duty-bound to return to captivity, he did not feel duty-bound to stay in

captivity. As soon as Captain Campbell returned to the camp, he set about trying to escape. He and a group of other prisoners spent nine months digging their way out of the camp before being captured on the Dutch border and sent back. He remained in the camp until 1918 and served in the military until 1925. Captain Campbell rejoined the military when World War II broke out in 1939 and served as the chief observer of the Royal Observer Corps on the Isle of Wight. He died in the Isle of Wight in July 1966, aged 81.

captivity. As soon as Captain Campbell returned to the camp, he set about trying to escape. He and a group of other prisoners spent nine months digging their way out of the camp before being captured on the Dutch border and sent back. He remained in the camp until 1918 and served in the military until 1925. Captain Campbell rejoined the military when World War II broke out in 1939 and served as the chief observer of the Royal Observer Corps on the Isle of Wight. He died in the Isle of Wight in July 1966, aged 81.

Friday, the 13th is not considered to be a lucky day…if you happen to be superstitious, but for almost 2500 Jewish people, as well as for Major Clarence L. Benjamin, Friday the 13th of April, 1945 would prove that Friday the 13th could be a very blessed day. While on a routine patrol a few miles northwest of Magdeburg, Benjamin and his unit came upon a railroad siding in a wooded ravine not far from the Elbe River. There, about 200 shabby looking civilians were sitting by the side of the road. Even in their shabby state, there was something immediately apparent about each one of these people, men and women, which drew immediate attention. These people were skeleton thin with starvation Their faces showed a sickness, and the way in which they stood…was like they were beaten and dejected, but there was something else. When they saw the Americans they began laughing in joy…if it could be called laughing. It was an outpouring of pure, near-hysterical relief. The reason, the unit soon found out was the railroad siding.

Friday, the 13th is not considered to be a lucky day…if you happen to be superstitious, but for almost 2500 Jewish people, as well as for Major Clarence L. Benjamin, Friday the 13th of April, 1945 would prove that Friday the 13th could be a very blessed day. While on a routine patrol a few miles northwest of Magdeburg, Benjamin and his unit came upon a railroad siding in a wooded ravine not far from the Elbe River. There, about 200 shabby looking civilians were sitting by the side of the road. Even in their shabby state, there was something immediately apparent about each one of these people, men and women, which drew immediate attention. These people were skeleton thin with starvation Their faces showed a sickness, and the way in which they stood…was like they were beaten and dejected, but there was something else. When they saw the Americans they began laughing in joy…if it could be called laughing. It was an outpouring of pure, near-hysterical relief. The reason, the unit soon found out was the railroad siding.

Standing silently on the tracks of the siding was a long string of grimy, ancient boxcars. On the banks by the tracks, trying to get some pitiful comfort from the thin April sun, sat a multitude of people of varying stages of misery. They sat motionless in despair. When they group sighted the Americans, a great stir went through this strange camp. Those who were able rushed toward the Major’s jeep and the two light tanks. On the hill to the left people were resting…some forever. About sixteen people died of starvation before food could be brought to the train. They simply couldn’t hold out any longer.

As the Major soothed the people, he eventually found some who spoke English, and their story came out. This had been, and still was, a horror train. This train which contained about 2,500 Jews, had a few days previously left the Bergen-Belsen death camp. Men, women and children, were all loaded into a few available railway cars, some passenger and some freight, but mostly the typical antiquated freight cars, called “40 and 8” cars. The term, from World War I, “40 and 8” meant that these cars would accommodate 40 men or 8 horses, but the cars were crammed with about 60 to 70 people, with standing room only for most of them. The cars were hot and it was hard to breathe. In all, the cars held about 2,500 Jews, far more than they should have.

The war was winding down, and the Nazis were trying to evacuate the concentration camps ahead of the Allied troops arrival. On April 10, 1945, three trains were sent from Bergen-Belsen with the purpose to move eastward from the Camp, to the Elbe River. They were told to reverse direction because of the rapidly advancing Russian Army. The train reversed direction and headed to Farsleben. There, they were then told that  they were heading into the advancing American Army. The train halted at Farsleben…awaiting further orders. The engineers received their orders…drive the train to, and onto the bridge over the Elbe River, and either blow it up, or just drive it off the end of the damaged bridge, with all of the cars of the train crashing into the river, and killing or drowning all of the occupants. While the engineers thought about this action, knowing that they too would be hurtling themselves to death, the Americans caught up to them. The arrival of the 743rd Tank Battalion was the only reason anyone came out of the trains alive. It was Friday the 13th…a very blessed day for these Jews. Not an ounce of bad luck there.

they were heading into the advancing American Army. The train halted at Farsleben…awaiting further orders. The engineers received their orders…drive the train to, and onto the bridge over the Elbe River, and either blow it up, or just drive it off the end of the damaged bridge, with all of the cars of the train crashing into the river, and killing or drowning all of the occupants. While the engineers thought about this action, knowing that they too would be hurtling themselves to death, the Americans caught up to them. The arrival of the 743rd Tank Battalion was the only reason anyone came out of the trains alive. It was Friday the 13th…a very blessed day for these Jews. Not an ounce of bad luck there.