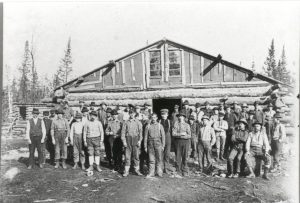

loggers

Established as a national forest in 1909, Superior National Forest is located in far northern Minnesota. Big pine timber logging began in the Superior National Forest in the 1890s and continued into the 1920s. Logging was not easy in Superior National Forest, and much of the area remained untouched because of the border lakes region, which presented numerous challenges to the logging companies in accessing and harvesting the stands of timber. In the 1890s, vast extents of the border lakes forests had been stripped away in Michigan and Wisconsin. The early logging was accomplished by means of river driving of logs. That was one of the types of logging that my grandfather was involved in. The logs were cut down,and then floated down the river to the saw mills. The method was a good one, but it could also be dangerous. Many a man was pinched between the logs, and many died. I’m very thankful my grandfather, Allen Luther Spencer was not one of those poor men who lost their lives doing this job. As timber near rivers became depleted, railroad logging became the primary method of getting the wood to the mill. Frozen ground conditions in the winter steered the logging industry to build ice roads providing greater access to timber stands. Logging after 1929 focused more and more on pulp species and the wood products industry.

Established as a national forest in 1909, Superior National Forest is located in far northern Minnesota. Big pine timber logging began in the Superior National Forest in the 1890s and continued into the 1920s. Logging was not easy in Superior National Forest, and much of the area remained untouched because of the border lakes region, which presented numerous challenges to the logging companies in accessing and harvesting the stands of timber. In the 1890s, vast extents of the border lakes forests had been stripped away in Michigan and Wisconsin. The early logging was accomplished by means of river driving of logs. That was one of the types of logging that my grandfather was involved in. The logs were cut down,and then floated down the river to the saw mills. The method was a good one, but it could also be dangerous. Many a man was pinched between the logs, and many died. I’m very thankful my grandfather, Allen Luther Spencer was not one of those poor men who lost their lives doing this job. As timber near rivers became depleted, railroad logging became the primary method of getting the wood to the mill. Frozen ground conditions in the winter steered the logging industry to build ice roads providing greater access to timber stands. Logging after 1929 focused more and more on pulp species and the wood products industry.

Soon, it became evident that the logging industry, while a good a profitable industry, had the potential to deplete the natural resources in the Superior National Forest. In 1921, Arthur Carhart (Forest Landscape Architect) published “Preliminary Prospectus: An Outline Plan for the Recreational Development of the Superior National Forest.” It was released following a survey conducted by Carhart and Forest Guard Soderback in the Boundary Waters region. This publication began to set the framework for the future designation of the BWCAW.

In 1930, Shipstead-Newton-Nolan Act was passed placing restrictions aimed at preserving the wilderness nature of lake and stream shorelines. By 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt designated the Quetico-Superior Committee to work with government agencies in the conservation, preservation, and use of northeast Minnesota’s wilderness areas. 1948 brought the Thye-Blatnik Act authorized the federal government to acquire private land holdings within roadless areas, thereby increasing federal acreage within the boundary waters roadless area. In 1949, the passage of Executive Order #10092, established an airspace boundary over the boundary waters roadless area. Highly controversial, this order effectively ended a particular type of recreation in the boundary waters, that of the remote fly-in resort. Resort operators had until 1951 to halt air traffic within 4000 feet of the roadless area.In 1958, The Superior Roadless Areas were renamed the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA). Conflict over motorized use in the roadless area increased during this time. The passage of the national Wilderness Act in 1964, with special provision regarding the BWCA, allowed some motorized use

and logging within the Boundary Water’s wilderness boundaries, but by 1978, with the passage of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act, which was specific to the BWCAW. This legislation eliminated logging and snowmobiling, restricted mining and allowed motorboats on 1/4 of the water area. While logging is necessary, I can’t help but agree with the preservation of the beautiful Superior National Forest.

and logging within the Boundary Water’s wilderness boundaries, but by 1978, with the passage of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act, which was specific to the BWCAW. This legislation eliminated logging and snowmobiling, restricted mining and allowed motorboats on 1/4 of the water area. While logging is necessary, I can’t help but agree with the preservation of the beautiful Superior National Forest.

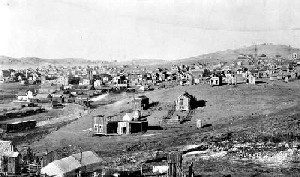

In the old west, few women went on to get a higher education, and even fewer became doctors. It was thought of as a man’s occupation, and the few women who dared to go into that field, were often looked at with distrust, and even disdain. People thought that women belonged in the home raising a family. Some didn’t even attempt to hide the dislike of women in medicine. Susan Anderson, MD was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1870. Her family moved to the mining camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado during her childhood. In 1893, Anderson left Cripple Creek to attend medical school at the University of Michigan. She graduated in 1897. During her time in medical school, Anderson contracted tuberculosis and soon returned to her family in Cripple Creek, where she set up her first practice.

In the old west, few women went on to get a higher education, and even fewer became doctors. It was thought of as a man’s occupation, and the few women who dared to go into that field, were often looked at with distrust, and even disdain. People thought that women belonged in the home raising a family. Some didn’t even attempt to hide the dislike of women in medicine. Susan Anderson, MD was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1870. Her family moved to the mining camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado during her childhood. In 1893, Anderson left Cripple Creek to attend medical school at the University of Michigan. She graduated in 1897. During her time in medical school, Anderson contracted tuberculosis and soon returned to her family in Cripple Creek, where she set up her first practice.

Anderson spent the next three years sympathetically tending to patients, but her father insisted that Cripple Creek, a lawless mining town at the time. He felt like it was no place for a woman, so Anderson moved to Denver. In Denver, she had a tough time securing patients. The people in Denver were reluctant to see a woman doctor. She then moved to Greeley, Colorado, where she worked as a nurse for six years. Somehow, people accepted a woman as a nurse, probably because they looked at it as just following the orders of the doctor, who was ultimately in charge.

Her tuberculosis got worse during this time, so she felt she needed a more cold and dry climate. She made the  decision to move to Fraser, Colorado in 1907. Fraser’s elevation of over 8,500 feet, definitely made the area cold and dry. Anderson was most concerned with getting her disease under control and didn’t open a practice. She didn’t even tell people that she was a doctor. Nevertheless, the word soon got out and the locals began to ask for her advice on various ailments, which soon led to her practicing her skills once again. Her reputation spread as she treated families, ranchers, loggers, railroad workers, and even an occasional horse or cow, which was not uncommon at the time. The vast majority of her patients required her to make house calls, though she never owned a horse or a car. Instead, she dressed in layers, wore high hip boots, and trekked through deep snows and freezing temperatures to reach her patients. Now that is dedication…especially for a woman trying to recover from Tuberculosis.

decision to move to Fraser, Colorado in 1907. Fraser’s elevation of over 8,500 feet, definitely made the area cold and dry. Anderson was most concerned with getting her disease under control and didn’t open a practice. She didn’t even tell people that she was a doctor. Nevertheless, the word soon got out and the locals began to ask for her advice on various ailments, which soon led to her practicing her skills once again. Her reputation spread as she treated families, ranchers, loggers, railroad workers, and even an occasional horse or cow, which was not uncommon at the time. The vast majority of her patients required her to make house calls, though she never owned a horse or a car. Instead, she dressed in layers, wore high hip boots, and trekked through deep snows and freezing temperatures to reach her patients. Now that is dedication…especially for a woman trying to recover from Tuberculosis.

During the many years that “Doc Susie,” which she familiarly became known as, practiced in the high mountains of Grand County, one of her busiest times was during the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919. Like people all over the world, Fraser locals also became sick in great numbers, and Dr Anderson found herself rushing from one deathbed to the next.

Another busy time for her was when the six-mile Moffat Tunnel was being built through the Rocky Mountains. Not long after construction began, she found herself treating numerous men who were injured during  construction. During this time, she was also asked to become the Grand County Coroner, a position that enabled her to confront the Tunnel Commission regarding working conditions and accidents. She hoped to make a difference. In the five years it took to complete the tunnel, there were about 19 who died and hundreds injured.

construction. During this time, she was also asked to become the Grand County Coroner, a position that enabled her to confront the Tunnel Commission regarding working conditions and accidents. She hoped to make a difference. In the five years it took to complete the tunnel, there were about 19 who died and hundreds injured.

Unlike physicians of today, Dr Anderson never became “rich” practicing her skills. Im not even sure you would say she made a middle class living, because she was often paid in firewood, food, services, and other items that could be bartered. Doc Susie continued to practice in Fraser until 1956. She died in Denver on April 16, 1960 and was buried in Cripple Creek, Colorado.