lithuania

Wars leave unfortunate consequences, one of the biggest being orphaned children. World War II is no exception to that rule. After the surrender of Germany, the nation was basically split into four sections…the American Zone, the Soviet Zone, the British Zone, and the French Zone. It was all part of the denazification process. The term denazification refers to the removal of the physical symbols of the Nazi regime. In 1957 the West German government re-issued World War II Iron Cross medals, among other decorations, without the swastika in the center. That was just one of the ways that the Nazi regime was removed from Germany.

Wars leave unfortunate consequences, one of the biggest being orphaned children. World War II is no exception to that rule. After the surrender of Germany, the nation was basically split into four sections…the American Zone, the Soviet Zone, the British Zone, and the French Zone. It was all part of the denazification process. The term denazification refers to the removal of the physical symbols of the Nazi regime. In 1957 the West German government re-issued World War II Iron Cross medals, among other decorations, without the swastika in the center. That was just one of the ways that the Nazi regime was removed from Germany.

Another way was the Denazified School System and the denazification of the rest of the German government…which was then reassembled without the Nazi symbolism. With the school system effectively out of commission, the children of Berlin had very little or even no structure in their lives at all. These were children whose lives had been shredded by the war, many of whom had been orphaned by the conflict or had lost at least one parent. That lead to an overall lack of adult supervisors. Children, and especially teens and preteens, roamed the streets in packs. The situation was especially difficult for the children who had lost both parents. There weren’t any real orphanages either, and so these children formed their own “families” on the streets…like street gangs. These children were known as German “wolf children” also known as “Wolfskinder,” but the reality was that they were simply the forgotten orphans of World War II.

The schools eventually reopened, but they were often in half-ruined facilities, that were underfunded and understaffed, with some schools reporting student-to-faculty ratios of 89 to 1. That kind of a classroom ratio is far too big to be able to effectively teach the students. And the re-opened schools didn’t really address the issue of these orphaned “wolf children” who were often in hiding whenever authorities were around. These children were most likely afraid of authority, because it was the authorities who got their parents killed in the first place. Many of these children were forced to flee what was then East Prussia to Lithuania at the end of World War II. They felt like the German government had failed them. These children survived hunger, cold, and the loss of their identity, and the German government had long overlooked them, so why would they trust the government now.

No one really knows just how many “wolf children” there were. That number can only be estimated. Some say there were up to 25,000 of them roaming the woods and swamps of East Prussia and Lithuania after 1945. Russians were actually forbidden from taking in these “fascist children.” These children were actually told to go to Lithuania and given the promise that there would be food there. When they arrived, they couldn’t speak the language and they had no papers, so they had no identity…no one could even know their names. Those who were taken in often had every shred of memorabilia from their past stripped from them and tossed in the trash. That was the last part of who they really were. It was the price they would pay for food, safety, and security; and it was a failure of the German government, and the four nations who were in charge of reorganizing Germany. I suppose some would disagree with me on that note, but the reality is plain to see. If these children came across kind locals, the “Vokietukai” or little Germans, in Lithuanian, as they were known, were helped with buckets of soup in front of the doors, giving the children a little nourishment. If the residents were not so kind, they would set their dogs on the children.

While the “Vokietukai” had many struggles in Lithuania, life was still better than the fate that awaited the

children who were too weak to make it to the Baltic states. There were thousands of these children, and they were sent to Soviet homes run by the military administration. That was the fate of approximately 4,700 German children in 1947, according to historian Ruth Leiserowitz, who has researched the fates of wolf children. Later that year, many of them were sent to the Soviet occupation zone. That zone later became the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Those poor children traveled in freight trains without any straw to sleep on…similar the Holocaust deportation years. These children were young…between 2 and 16 years of age. They arrived in East Germany after four days and four nights…really more dead than alive. There, they were put in orphanages or adopted by avid Communists. They never really escaped Communism…and that is the saddest part of all.

children who were too weak to make it to the Baltic states. There were thousands of these children, and they were sent to Soviet homes run by the military administration. That was the fate of approximately 4,700 German children in 1947, according to historian Ruth Leiserowitz, who has researched the fates of wolf children. Later that year, many of them were sent to the Soviet occupation zone. That zone later became the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Those poor children traveled in freight trains without any straw to sleep on…similar the Holocaust deportation years. These children were young…between 2 and 16 years of age. They arrived in East Germany after four days and four nights…really more dead than alive. There, they were put in orphanages or adopted by avid Communists. They never really escaped Communism…and that is the saddest part of all.

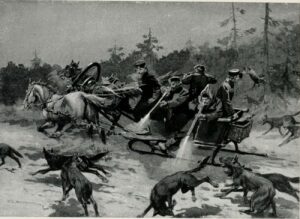

A truce in the context of war, doesn’t always mean a permanent end to the fighting. That is a fact that has often amazed me. If a war can be put “on hold” for a specific reason and a specified timeframe, why must the fighting then resume like the truce never happened? Nevertheless, resume it usually did. Such a truce happened between the German forces fighting the Russians forces in satellite regions like Lithuania and Belarus during World War I. The fighting raged in many different places at that time and continued through the winter of 1917.

A truce in the context of war, doesn’t always mean a permanent end to the fighting. That is a fact that has often amazed me. If a war can be put “on hold” for a specific reason and a specified timeframe, why must the fighting then resume like the truce never happened? Nevertheless, resume it usually did. Such a truce happened between the German forces fighting the Russians forces in satellite regions like Lithuania and Belarus during World War I. The fighting raged in many different places at that time and continued through the winter of 1917.

The intense fighting throughout the heavily forested region and had an unexpected side effect. Any time humans move into an area, the animal  population instinctively moves deeper into wilderness areas where there is less interaction with people, but when the winter is harsh and food becomes scarce, the animals can become as desperate as the humans. In that particular area at that particular time, the Russian wolves were starving. Any prey they might have been able to hunt had vacated because of the intense fighting, and so they had resorted to taking the bodies of the fallen soldiers for food. When there wasn’t enough of that, they began to actively hunt the soldiers, so now the soldiers of the Russian and the German armies had a whole new enemy, and this one could not be reasoned with.

population instinctively moves deeper into wilderness areas where there is less interaction with people, but when the winter is harsh and food becomes scarce, the animals can become as desperate as the humans. In that particular area at that particular time, the Russian wolves were starving. Any prey they might have been able to hunt had vacated because of the intense fighting, and so they had resorted to taking the bodies of the fallen soldiers for food. When there wasn’t enough of that, they began to actively hunt the soldiers, so now the soldiers of the Russian and the German armies had a whole new enemy, and this one could not be reasoned with.

The wolves had progressed from raiding villages to taking corpses to accosting groups of soldiers outright, so  the two armies mutually decided that it was necessary to call a truce so they could rid the area of the unexpected mutual enemy…roving bands of gigantic Russian wolves. They were genuinely in fear for their lives. Wolves often attack in the dark and go for the weakest link or when people are sleeping. It became obvious that this would be a fight to the end…of one or the other…man or beast. So, both armies agreed to a temporary truce and went on a joint campaign of destruction. The wolves could not be allowed to stay, for the sake of anyone in the area. The two armies slew hundreds of wolves, and then simply resumed their fight. How very strange that seems to me, but I guess it probably wasn’t up to the soldiers to walk away from the war.

the two armies mutually decided that it was necessary to call a truce so they could rid the area of the unexpected mutual enemy…roving bands of gigantic Russian wolves. They were genuinely in fear for their lives. Wolves often attack in the dark and go for the weakest link or when people are sleeping. It became obvious that this would be a fight to the end…of one or the other…man or beast. So, both armies agreed to a temporary truce and went on a joint campaign of destruction. The wolves could not be allowed to stay, for the sake of anyone in the area. The two armies slew hundreds of wolves, and then simply resumed their fight. How very strange that seems to me, but I guess it probably wasn’t up to the soldiers to walk away from the war.

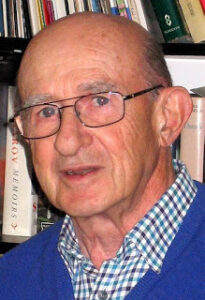

What would you do if your life had been ripped apart by a group of people who really knew nothing about you or your people, but hated you and them anyway. That was the position in which Joseph Harmatz found himself. Born in Rokiškis, Lithuania into a prosperous family, Harmatz and his family were transferred to the Vilnius Ghetto on January 23, 1925, after the occupation of Lithuania by Nazi Germany. It was the worst time in his life. His youngest brother and all of his grandparents were killed and his older brother died during a military action. His despondent father committed suicide. Harmatz was left alone with his mother at the age of 16. He couldn’t stand the way things were, so he left the ghetto through the sewers and joined a band of guerrillas fighting the Nazis. Harmatz managed to survive the Holocaust, and after the war, he became part of Nakam (Hebrew for Revenge) also known as the Avengers. The Nakam was a group of 50 former underground fighters led by Abba Kovner. Their goal was to avenge the deaths of the six million Jewish victims of Nazi extermination efforts in the Holocaust. The true goal according to Harmatz was to facilitate the death of as many Germans as possible, with the group planning “to kill six million Germans, one for every Jew slaughtered by the Germans,” acknowledging that the effort “was revenge, quite simply. Were we not entitled to our revenge, too?”

What would you do if your life had been ripped apart by a group of people who really knew nothing about you or your people, but hated you and them anyway. That was the position in which Joseph Harmatz found himself. Born in Rokiškis, Lithuania into a prosperous family, Harmatz and his family were transferred to the Vilnius Ghetto on January 23, 1925, after the occupation of Lithuania by Nazi Germany. It was the worst time in his life. His youngest brother and all of his grandparents were killed and his older brother died during a military action. His despondent father committed suicide. Harmatz was left alone with his mother at the age of 16. He couldn’t stand the way things were, so he left the ghetto through the sewers and joined a band of guerrillas fighting the Nazis. Harmatz managed to survive the Holocaust, and after the war, he became part of Nakam (Hebrew for Revenge) also known as the Avengers. The Nakam was a group of 50 former underground fighters led by Abba Kovner. Their goal was to avenge the deaths of the six million Jewish victims of Nazi extermination efforts in the Holocaust. The true goal according to Harmatz was to facilitate the death of as many Germans as possible, with the group planning “to kill six million Germans, one for every Jew slaughtered by the Germans,” acknowledging that the effort “was revenge, quite simply. Were we not entitled to our revenge, too?”

Their main target was Stalag XIII-D, a prisoner-of-war camp built on what had been the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg. Interned in the camp were 12,000 members of the SS (Schutzstaffel or Protection Squads). These prisoners were involved in running concentration camps and other aspects of the Final  Solution…Nazi Germany’s horrific policy of deliberate and systematic genocide across German-occupied Europe. In April 1946, a member of the Nakam got a job as a baker, and he had a plan. He baked arsenic into 3,000 loaves of bread that were to be fed to the prisoners. Nearly 2,000 prisoners became ill and were thought to be seriously ill. American authorities thought that the arsenic had got onto the crust of the bread by accident, having been used as an insecticide in the wheat fields. During the investigation, United States Army investigators found enough arsenic to have killed 60,000 people and Nakam claimed they had killed several hundred victims, but declassified documents obtained by Associated Press in 2016 stated there were no casualties.

Solution…Nazi Germany’s horrific policy of deliberate and systematic genocide across German-occupied Europe. In April 1946, a member of the Nakam got a job as a baker, and he had a plan. He baked arsenic into 3,000 loaves of bread that were to be fed to the prisoners. Nearly 2,000 prisoners became ill and were thought to be seriously ill. American authorities thought that the arsenic had got onto the crust of the bread by accident, having been used as an insecticide in the wheat fields. During the investigation, United States Army investigators found enough arsenic to have killed 60,000 people and Nakam claimed they had killed several hundred victims, but declassified documents obtained by Associated Press in 2016 stated there were no casualties.

According to Harmatz’s son, his father had no regret for his attempts to kill the German prisoners. He said he was only “sorry that it didn’t work.” Harmatz wrote a book in 1998, called “From the Wings” in which he stated that the poisoning plot had the approval of Chaim Weizmann, though David Ben-Gurion and Zalman Shazar were both against the plan. An earlier attempt to poison the water in a number of German cities failed after  Kovner was arrested by British forces on a ship on which the poison had been hidden, and had been thrown overboard to prevent its capture. The group was so filled with hatred that they wanted all Germans killed, even if they had nothing to do with the Holocaust. Looking back, after much soul searching, Harmatz was thankful that the plot to poison the water supplies in German cities had failed, saying that it “would have harmed efforts to create an incipient State of Israel and would have led to charges of moral equivalence between actions of Germans and Jews. Another effort to kill Nazi war criminals on trial at Nuremberg failed when the group was unable to find any US Army guards willing to participate.”

Kovner was arrested by British forces on a ship on which the poison had been hidden, and had been thrown overboard to prevent its capture. The group was so filled with hatred that they wanted all Germans killed, even if they had nothing to do with the Holocaust. Looking back, after much soul searching, Harmatz was thankful that the plot to poison the water supplies in German cities had failed, saying that it “would have harmed efforts to create an incipient State of Israel and would have led to charges of moral equivalence between actions of Germans and Jews. Another effort to kill Nazi war criminals on trial at Nuremberg failed when the group was unable to find any US Army guards willing to participate.”

Harmatz emigrated to Israel in 1950, and worked to aid Jews resettling from countries around the world. He headed World ORT, a Jewish non-profit organization that promotes education and training in communities around the world, from 1960 to 1994. A long-time resident of Tel Aviv, Harmatz died at at his home on September 22, 2016. He was 91 years old, and was survived by two sons.