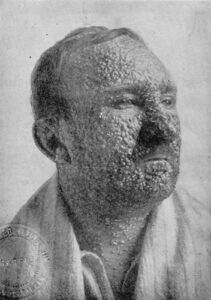

leprosy

When we think of vaccinations, most of us think of modern-day medicine, but that wasn’t always the case. There have been serious diseases out there for centuries, and in fact, since Biblical days. Many of those diseases have been cured these days, or they are at least manageable, but in the 1700s, a disease like Smallpox was deadly. Others like Leprosy were just as bad. I’m sure that any doctor in those days cringed at having to make a diagnosis like that, because he knew that he was pronouncing a death sentence on his patient, and basically all he could do was to tell them to get their affairs in order and go into hiding to die, because their case was one with no hope of survival.

When we think of vaccinations, most of us think of modern-day medicine, but that wasn’t always the case. There have been serious diseases out there for centuries, and in fact, since Biblical days. Many of those diseases have been cured these days, or they are at least manageable, but in the 1700s, a disease like Smallpox was deadly. Others like Leprosy were just as bad. I’m sure that any doctor in those days cringed at having to make a diagnosis like that, because he knew that he was pronouncing a death sentence on his patient, and basically all he could do was to tell them to get their affairs in order and go into hiding to die, because their case was one with no hope of survival.

Vaccinations, for any disease, start out as trial and error, and Smallpox was no exception to that rule, but Edward Jenner, while still a medical student noticed that milkmaids who had contracted a disease called cowpox, which caused blistering on cow’s udders, did not catch smallpox. Unlike smallpox, which caused severe skin eruptions and dangerous fevers in humans, cowpox led to few ill symptoms in these women. I guess it takes a  medically trained mind to connect the two situations and find whatever small similarity there is between the two diseases…and then decide to experiment with a possibility that no one else saw…or to decide not to.

medically trained mind to connect the two situations and find whatever small similarity there is between the two diseases…and then decide to experiment with a possibility that no one else saw…or to decide not to.

Jenner was that kind of a medical mind. By 1796, Jenner was an English country doctor, who hailed from Gloucestershire. On May 14, 1796, he took fluid from a cowpox blister and scratched it into the skin of James Phipps, an eight-year-old boy. A single blister rose up on the spot, but James soon recovered. On July 1, Jenner inoculated the boy again, this time with smallpox matter, and amazingly, no disease developed. The vaccine was a success. The medical world at the time, went wild. Doctors all over Europe soon adopted Jenner’s innovative technique, leading to a drastic decline in new sufferers of the devastating  disease, as well as many lives saved.

disease, as well as many lives saved.

Following Jenner’s model, scientists in the 19th and 20th centuries, scientists developed new vaccines to fight numerous deadly diseases, among them polio, whooping cough, measles, tetanus, yellow fever, typhus, and hepatitis B. The lists of vaccines, goes on and on, all using the same model. More sophisticated smallpox vaccines were also developed and by 1970 international vaccination programs, such as those undertaken by the World Health Organization, had eliminated smallpox worldwide. Many people, these days would question the World Health Organization, and its motives, but there was a time that vaccines were very helpful and saved a lot of lives. I think it is sad that politics has made its entrance into the world of vaccines, because the lack of trust we have now is making the World Health Organization more of a hindrance than a help.

Many of us have heard of “dance mania” or “dance fever,” but I wonder how many people realize that those were real things. There have been a number of times in history when people were suddenly compelled to dance without stopping. In fact, they really couldn’t stop until they fell down with exhaustion. Then they would sleep a while, and start all over again. Many times the victim of this disease, would cry out in pain, begging someone to help them. They could not stop. Their feel would blister and bleed. Their muscles would spasm. Tears would flow from their eyes, but still they danced. Some people danced until they actually fell down dead.

Many of us have heard of “dance mania” or “dance fever,” but I wonder how many people realize that those were real things. There have been a number of times in history when people were suddenly compelled to dance without stopping. In fact, they really couldn’t stop until they fell down with exhaustion. Then they would sleep a while, and start all over again. Many times the victim of this disease, would cry out in pain, begging someone to help them. They could not stop. Their feel would blister and bleed. Their muscles would spasm. Tears would flow from their eyes, but still they danced. Some people danced until they actually fell down dead.

The Strasbourg plague started with Frau Troffea in July of 1518. That day, she just stepped outside her small home in Strasbourg and started to dance. She might have seemed happy, but she didn’t stop. Frau Troffea danced the entire day. Her husband was not happy. No cleaning was done, no cooking, and if they had children, they weren’t taken care of either. She only stopped dancing when she collapsed that night for a few hours of restless sleep. Then, with the sun rise, she began dancing again. To the horror of her husband, a crowd gathered around his dancing wife, who swayed to the sound of silence. There was no music…except maybe in her head. She paid no attention to anything going on around her. She just danced, even though her feet were bloody and bruised. It was almost as if she was just crazy, but that couldn’t be it, because within days, at least thirty other dancers had joined Frau Troffea. It was just the beginning of the strangest plague to strike medieval Europe. The people called it “dancing mania,” and it soon spread to even more people in Strasbourg. A reporter at that time, Daniel Specklin said that there were “more than one hundred” dancing at the same time. Someone else estimated the number at closer to four hundred. The strange epidemic quickly became a crisis for the city of Strasbourg, and the city council had no idea how to stop the dancing, which is a strange idea to me anyway. What could the city council do, if the doctors couldn’t help?

The only thing anyone was sure of, was that…the dancers were not happy. They writhed in pain. They begged for mercy. They screamed for help. As summer stretched on, the dancing epidemic started to claim lives. One chronicle reported that during the heat of the summer, as many as fifteen people died every day from dancing. It makes sense, they probably couldn’t stop to eat or drink. Exhaustion, dehydration, and starvation finally took their toll, and the victim simply died. Thinking it might be a curse, the city cracked down on the possible connection to sin. Brothels and gambling houses were closed. Everyone knew that gaming and prostitution angered the saints, who might have sent the dancing plague to punish Strasbourg. So, the city rounded up all the “loose persons” and banished them from the city. It didn’t help. They prayed and lit candles, hoping that a return to their faith might lift the “curse” for the town. They banned dancing, effectively making all the victims, “criminals” as well.

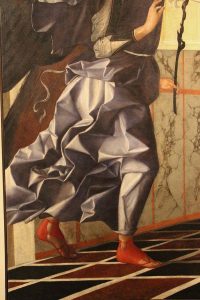

Desperate, as the end of summer neared and the dancing mania continued, the city took a drastic step. A reporter of the time described the cure. “They sent many on wagons to St. Vitus,” a shrine at the top of a mountain. The dancers continued to fall down in front of the altar, so the priest said Mass over them, and “they were given a little cross and red shoes, on which the sign of the cross had been made in holy oil, on both the

tops and the soles.” It was thought that they were possessed. The red shoes did the trick. The dancing epidemic slowly came to an end, and most of the dancers regained control of their bodies. The strange ailment started to be called “St. Vitus’ Dance,” either because the saint had cured the dancers, or because he was responsible for the original curse. Strange idea either way. Whether they were possessed, or the “illness” just ran it’s course, the trip to Saint Vitus marked the beginning of the end of the Dancing Plague. It is now believed that the people suffered from mass hysteria, due to the stresses of the day. A Small Pox plague and a Leprosy plague had been through the area, as well as several years of failed crops and famine. It makes sense I guess, but what a strange way for it to manifest. Apparently, a trip to the church to see the priest was enough to calm their fears and stop the plague.

tops and the soles.” It was thought that they were possessed. The red shoes did the trick. The dancing epidemic slowly came to an end, and most of the dancers regained control of their bodies. The strange ailment started to be called “St. Vitus’ Dance,” either because the saint had cured the dancers, or because he was responsible for the original curse. Strange idea either way. Whether they were possessed, or the “illness” just ran it’s course, the trip to Saint Vitus marked the beginning of the end of the Dancing Plague. It is now believed that the people suffered from mass hysteria, due to the stresses of the day. A Small Pox plague and a Leprosy plague had been through the area, as well as several years of failed crops and famine. It makes sense I guess, but what a strange way for it to manifest. Apparently, a trip to the church to see the priest was enough to calm their fears and stop the plague.