indigenous

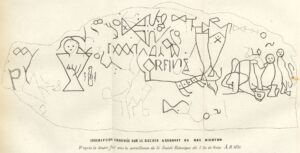

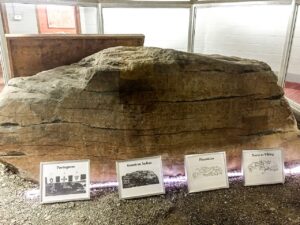

The Dighton Rock is a 40-ton boulder that was found in the riverbed of the Taunton River at located Berkley, Massachusetts, over 300 years ago. The rock has puzzling petroglyphs on it that have apparently never been able to be deciphered. Dighton Rock is one of the greatest mysteries of Massachusetts. The boulder is slanted and has six sides. It is approximately 5′ high, 9½’ wide, and 11′ long. All of those 300 years, people have wondered about the lines, geometric shapes, drawings, and writing that appear on the rock and who created them. They wanted to figure it out. What did it mean? Who made those markings, so many years ago. No one really knows how long ago the marks were made, only about how long ago it was found.

The Dighton Rock is a 40-ton boulder that was found in the riverbed of the Taunton River at located Berkley, Massachusetts, over 300 years ago. The rock has puzzling petroglyphs on it that have apparently never been able to be deciphered. Dighton Rock is one of the greatest mysteries of Massachusetts. The boulder is slanted and has six sides. It is approximately 5′ high, 9½’ wide, and 11′ long. All of those 300 years, people have wondered about the lines, geometric shapes, drawings, and writing that appear on the rock and who created them. They wanted to figure it out. What did it mean? Who made those markings, so many years ago. No one really knows how long ago the marks were made, only about how long ago it was found.

The rock has been studied by many people over the years. In 1680, English colonist Reverend John Danforth drew a copy of the petroglyphs. That drawing has been preserved in the British Museum, but there are conflicts as to the accuracy of the drawing. Some say the markings aren’t exactly the same as the rock. In something as intricate as petroglyphs, accuracy would be of vital importance. Ten years later, in 1690 Reverend Cotton Mather described the rock in his book, The Wonderful Works of God Commemorated: “Among the other Curiosities of New England, one is that of a mighty Rock, on a perpendicular side whereof by a River, which at High Tide covers part of it, there are very deeply Engraved, no man alive knows How or When about half a score Lines, near Ten Foot Long, and a foot and half broad, filled with strange Characters: which would suggest as odd Thoughts about them that were here before us, as there are odd Shapes in that Elaborate Monument…”

One theory suggests that Indigenous peoples of North America…who were known to have inscribed petroglyphs in rocks (a schematic face on the Dighton Rock is similar to an Indian petroglyph in Eastern Vermont) made the markings. A second theory suggests that Ancient Phoenicians made them was proposed in 1783 by Ezra Stiles in his “Election Sermon” as the “descendants of the sons of Japheth.” Still another theory suggests that the Norse might have made them. That theory was proposed by Carl Christian Rafn in 1837, but it was rejected by archaeologists such as TD Kendrick and Kenneth Feder. Others suggested that the Portuguese may have made them. That was proposed in 1912 by Edmund B Delabarre, who (after seeing Portuguese writing) believed that they then used the rock for their own inscriptions. Delabarre wrote that “markings on the Dighton Rock suggest that Miguel Corte-Real reached New England. Delabarre stated that the markings were abbreviated Latin, and the message, translated into English, reads as follows: “I, Miguel Cortereal, 1511. In this place, by the will of God, I became a chief of the Indians.'” Of his findings, Douglas Hunter wrote in his book “Reconstructing the

history of writing about Dighton Rock” provides copious evidence and analysis debunking the Corte-Real origin myth. Lastly, the Chinese have also been suggested as a possible source, proposed by Gavin Menzies in his 2002 book “1421: The Year China Discovered America.” I don’t think we’ll ever know who made them or what they mean.

history of writing about Dighton Rock” provides copious evidence and analysis debunking the Corte-Real origin myth. Lastly, the Chinese have also been suggested as a possible source, proposed by Gavin Menzies in his 2002 book “1421: The Year China Discovered America.” I don’t think we’ll ever know who made them or what they mean.

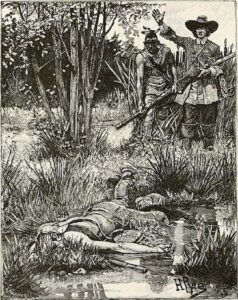

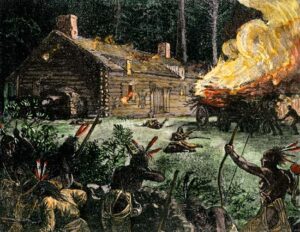

There have been many deadly wars in American history, but the deadliest war of them all took place during the 1670s. Technically, that was before the United States was even a nation. King Philip’s War, named for Metacom, the Wampanoag chief who adopted the name Philip because of the friendly relations between his father Massasoit and the Mayflower Pilgrims. The war pitted colonists and their indigenous allies (members of the Mohegan and Mohawk nations) in New England, against Philip’s (Metacom’s) Indigenous populations who didn’t want to be told what to do by the colonists in America. King Philip’s War was sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom’s War, Metacomet’s War, Pometacomet’s Rebellion, or Metacom’s Rebellion. The conflict lasted from 1675 to 1678. The war continued in the most northern reaches of New England until the signing of the Treaty of Casco Bay on April 12, 1678.

There have been many deadly wars in American history, but the deadliest war of them all took place during the 1670s. Technically, that was before the United States was even a nation. King Philip’s War, named for Metacom, the Wampanoag chief who adopted the name Philip because of the friendly relations between his father Massasoit and the Mayflower Pilgrims. The war pitted colonists and their indigenous allies (members of the Mohegan and Mohawk nations) in New England, against Philip’s (Metacom’s) Indigenous populations who didn’t want to be told what to do by the colonists in America. King Philip’s War was sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom’s War, Metacomet’s War, Pometacomet’s Rebellion, or Metacom’s Rebellion. The conflict lasted from 1675 to 1678. The war continued in the most northern reaches of New England until the signing of the Treaty of Casco Bay on April 12, 1678.

Massasoit, Metacom’s father had maintained a long-standing alliance with the colonists…since the days of the Mayflower, when the Wampanoag Indians and the pilgrims helped each other survive that first awful winter. When Metacom (1638–1676), Massasoit’s younger son, became tribal chief in 1662 after Massasoit’s death, he forsook his father’s alliance between the Wampanoags and the colonists after repeated violations by the colonists. The colonists insisted that the 1671 peace agreement should include the surrender of Native guns. They felt threatened by armed Indians. Tensions increased when three Wampanoags were hanged in Plymouth Colony in 1675 for the murder of another  Wampanoag. Suddenly, native raiding parties were attacking homesteads and villages throughout Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Maine. The attacks continued over the next six months, and the colonial militia retaliated. While the Narragansetts remained neutral, some of them participated in raids of colonial strongholds and militia, so colonial leaders claimed they were in violation of peace treaties.

Wampanoag. Suddenly, native raiding parties were attacking homesteads and villages throughout Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Maine. The attacks continued over the next six months, and the colonial militia retaliated. While the Narragansetts remained neutral, some of them participated in raids of colonial strongholds and militia, so colonial leaders claimed they were in violation of peace treaties.

The colonies assembled the largest army New England had mustered to that date, consisting of 1,000 militia and 150 Native allies. In November of 1675, Governor Josiah Winslow marshaled them to attack the Narragansetts. They attacked and burned Native villages throughout Rhode Island territory, culminating with the attack on the Narragansetts’ main fort in the Great Swamp Fight. It is estimated that 600 Narragansetts were killed, and their coalition was taken over by Narragansett sachem Canonchet. They pushed back the borders of the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Rhode Island colonies, burning towns as they went, including Providence in March 1676. The colonial militia fought back hard and soon overwhelmed the Native coalition. By the end of the war, the Wampanoags and their Narragansett allies were almost completely wiped out. On  August 12, 1676, Metacom fled to Mount Hope, where he was killed by the militia. The war was the greatest tragedy in seventeenth-century New England. Many believe it was the deadliest war in Colonial American history. In the space of little more than a year, 12 of the region’s towns were destroyed and many more were damaged. The economy of Plymouth and Rhode Island Colonies was all but ruined. They lost over a tenth of all men available for military service. More than half of New England’s towns were attacked by Natives. Hundreds of Wampanoags and their allies were publicly executed or enslaved, and the Wampanoags were left effectively landless and destitute.

August 12, 1676, Metacom fled to Mount Hope, where he was killed by the militia. The war was the greatest tragedy in seventeenth-century New England. Many believe it was the deadliest war in Colonial American history. In the space of little more than a year, 12 of the region’s towns were destroyed and many more were damaged. The economy of Plymouth and Rhode Island Colonies was all but ruined. They lost over a tenth of all men available for military service. More than half of New England’s towns were attacked by Natives. Hundreds of Wampanoags and their allies were publicly executed or enslaved, and the Wampanoags were left effectively landless and destitute.