indians

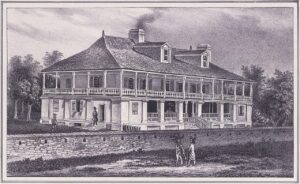

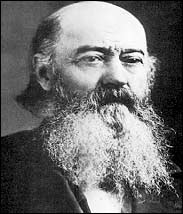

René-Auguste Chouteau Jr, who was best known as Auguste Chouteau, was the founder of Saint Louis, Missouri. While being a founder of a city is not necessarily such a strange thing, the way in which it came about is not so common. He was the only child of Marie-Thérèse (nee Bourgeois) and René Chouteau, born in either September 7th of either 1749 or 1750. René purportedly abused Marie-Thérèse, and abandoned her and René, so she returned to her pre-matrimonial home. She later remarried. In 1764, when Auguste was still a young man of just 13 years, his stepfather, Pierre Liguest sent him up the Missouri River from Fort Chartres, Illinois. Auguste was the leader of a company of 30 men. His mission was to select a site for a trading post. His stepfather must have considered the young man to be quite intelligent to put him in charge of such an enormous undertaking. Auguste didn’t let his stepfather down either. He chose a place that was not only perfect for the trading post, but would later become a great American city…Saint Louis, Missouri. After his stepfather’s death in 1778, Auguste succeeded him in the business and later formed a partnership with John Jacob Astor. Together they formed the American Fur Company. Auguste was 29 years old.

René-Auguste Chouteau Jr, who was best known as Auguste Chouteau, was the founder of Saint Louis, Missouri. While being a founder of a city is not necessarily such a strange thing, the way in which it came about is not so common. He was the only child of Marie-Thérèse (nee Bourgeois) and René Chouteau, born in either September 7th of either 1749 or 1750. René purportedly abused Marie-Thérèse, and abandoned her and René, so she returned to her pre-matrimonial home. She later remarried. In 1764, when Auguste was still a young man of just 13 years, his stepfather, Pierre Liguest sent him up the Missouri River from Fort Chartres, Illinois. Auguste was the leader of a company of 30 men. His mission was to select a site for a trading post. His stepfather must have considered the young man to be quite intelligent to put him in charge of such an enormous undertaking. Auguste didn’t let his stepfather down either. He chose a place that was not only perfect for the trading post, but would later become a great American city…Saint Louis, Missouri. After his stepfather’s death in 1778, Auguste succeeded him in the business and later formed a partnership with John Jacob Astor. Together they formed the American Fur Company. Auguste was 29 years old.

Chouteau married Marie Therese, the daughter of Jean-Gabriel Cerré, on September 21, 1786, at the Basilica of Saint Louis, King of France, which was a vertical-log church…long since replaced with the current church on the site. The apparently happy marriage united members of the two leading Saint Louis families. They were renowned for their hospitality, which helped strengthen his political position in the city and region. Together they had seven children…Auguste Aristide, Gabriel, Marie Thérèse Eulalie, Henry, Edward, Louise, and Emilie.

Auguste was commissioned colonel of the militia in 1808. His political career began in 1815 when he was appointed one of the commissioners to make treaties with the Indians who had fought on the British side in the War of 1812. The other two commissioners were Ninian Edwards and William Clark. I don’t suppose this would be a big step into politics, but it was an office, and the field of politics seems to take off from a smaller office.

In Saint Louis, he served as Justice of the Peace and as Judge of the Court of Common Pleas. He was also the first president of the Bank of Missouri, as well as several other important positions. Auguste made it his policy when dealing with the Indians, to treat them fairly. Because of that, he enjoyed their confidence and friendship until his death, which occurred on February 24, 1829.

In Saint Louis, he served as Justice of the Peace and as Judge of the Court of Common Pleas. He was also the first president of the Bank of Missouri, as well as several other important positions. Auguste made it his policy when dealing with the Indians, to treat them fairly. Because of that, he enjoyed their confidence and friendship until his death, which occurred on February 24, 1829.

When the Transcontinental Railroad opened in 1869, the people in the east finally had the chance to take a trip into the Wild West without having to move there or plan on spending months there visiting family. I can imagine that there were mixed emotions involved as they headed out. The Western dime novels had told of wild Indians, gunslingers, bank robberies, and of course, train robberies. It was almost enough to make them question the sanity of their intended trip into the wild, but nevertheless, they went.

When the Transcontinental Railroad opened in 1869, the people in the east finally had the chance to take a trip into the Wild West without having to move there or plan on spending months there visiting family. I can imagine that there were mixed emotions involved as they headed out. The Western dime novels had told of wild Indians, gunslingers, bank robberies, and of course, train robberies. It was almost enough to make them question the sanity of their intended trip into the wild, but nevertheless, they went.

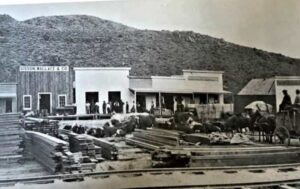

One of the great misconceptions of the Wild West is that it maybe wasn’t quite as wild as the Easterners had been told. In fact, the town of Palisade, Nevada, a state notoriously known for its wildness these days, like many other Wild West towns of the time, was actually very peaceful. In fact, the town had so few crimes that it didn’t even have an official sheriff. So, when the train began running through Palisade, and the train conductor  told the townspeople that railroad passengers were often disappointed at how these quiet towns were so different from how they were portrayed in the Western dime novels, he people of Palisade decided that something had to be done.

told the townspeople that railroad passengers were often disappointed at how these quiet towns were so different from how they were portrayed in the Western dime novels, he people of Palisade decided that something had to be done.

The townspeople, with the full knowledge and approval of the citizens of the town, the US Cavalry, and even a local Indian tribe, staged Western-style shootouts in the street, bank robberies, Indian battles, and whatever else they could think of. The whole purpose was to provide entertainment for the passing railroad travelers. After the train passed, life in the small town went back to its “dull, quiet, and peaceful” normal. I don’t know if the purpose was to bring in more tourists, to save face when it came to the Western dime novels, or maybe just to have a good laugh at the expense of the city-slickers. The reality is that many of the people back east, at that time, felt like their way of life was better than the “craziness” of the Wild West, and that to go have a look was a way of not only entertaining themselves, but also to prove that the West could not possibly be a peaceful place to live. Of course, while things could be violent and wild in the old West, it wasn’t always that

way. It’s also a possibility that the people had moved to the West wanted the people in the East to think that the West was a wild place, full of adventure. It was the whole purpose for going west anyway, wasn’t it…to find that adventure? Yes, that was the purpose for the move to the West. And that purpose had to be protected, by any means necessary…even theater.

way. It’s also a possibility that the people had moved to the West wanted the people in the East to think that the West was a wild place, full of adventure. It was the whole purpose for going west anyway, wasn’t it…to find that adventure? Yes, that was the purpose for the move to the West. And that purpose had to be protected, by any means necessary…even theater.

There was so much controversy over the control of the Black Hills. The Indians were told that the White man would stay out of the Black Hills, but when gold was discovered there, all bets were off. Before his defeat at the Battle of Little Big Horn, while he was still a Lieutenant Colonel, George Custer rode with his crew to the Black Hills of South Dakota in search of a location for a fort. That Custer Expedition of 1874 became a defining moment in the story of the Black Hills coming under the control of the United States. Things really got started in 1872, when Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano, basically set the stage for the expedition to the Black Hills. Delano was responsible for the Sioux territorial rights in the region. Delano sent a letter dated March 28, l872, which stated, “I am inclined to think that the occupation of this region of the country is not necessary to the happiness and prosperity of the Indians, and as it is supposed to be rich in minerals and lumber it is deemed important to have it freed as early as possible from Indian occupancy. I shall, therefore, not oppose any policy which looks first to a careful examination of the subject… If such an examination leads to the conclusion that country is not necessary or useful to Indians, I should then deem it advisable…to extinguish the claim of the Indians and open the territory to the occupation of the whites.”

There was so much controversy over the control of the Black Hills. The Indians were told that the White man would stay out of the Black Hills, but when gold was discovered there, all bets were off. Before his defeat at the Battle of Little Big Horn, while he was still a Lieutenant Colonel, George Custer rode with his crew to the Black Hills of South Dakota in search of a location for a fort. That Custer Expedition of 1874 became a defining moment in the story of the Black Hills coming under the control of the United States. Things really got started in 1872, when Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano, basically set the stage for the expedition to the Black Hills. Delano was responsible for the Sioux territorial rights in the region. Delano sent a letter dated March 28, l872, which stated, “I am inclined to think that the occupation of this region of the country is not necessary to the happiness and prosperity of the Indians, and as it is supposed to be rich in minerals and lumber it is deemed important to have it freed as early as possible from Indian occupancy. I shall, therefore, not oppose any policy which looks first to a careful examination of the subject… If such an examination leads to the conclusion that country is not necessary or useful to Indians, I should then deem it advisable…to extinguish the claim of the Indians and open the territory to the occupation of the whites.”

It was the beginning of major trouble in the Black Hills, because Delano’s remarks were in direct contradiction of terms defined in the 1868 Laramie Treaty which states: “…no persons except those designated herein … shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in the territory described in this article.” Delano singlehandedly broke the treaty with the Indians and blew up the situation in the Black Hills. Basically, he thought the Indians wouldn’t see the value in the Black Hills that he saw…gold. Well, the gold didn’t interest them, but the land did. Delano stated that the major reasons for exploration was that “Americans and representatives in Dakota Territory felt that there was too much land allotted for too few Sioux (estimated to number from 15 to 25,000 in 1872); and the existence of mineral and natural resources in the area.”

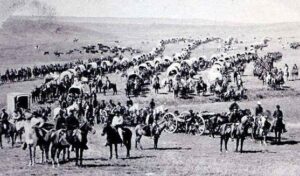

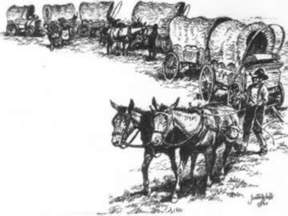

The American economy wasn’t in good shape at that time. Experts think that the Delano letter and other previous reports and rumors regarding the wealth of the Black Hills were the real forces behind the expedition of the following year. General Alfred H. Terry of the Headquarters of the Department of Dakota in Saint Paul formally ordered the exploration of the Black Hills on June 8, 1874. Enter Custer…who was told to look for a site for Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, which ended up being located 7 miles south of Mandan, North Dakota, not in the Black Hills at all. Of course, the fort was likely to be used to protect the settlers and prospectors who were expected to flood the Black Hills. Custer’s expedition departed on July 2, 1874. Custer’s expedition, which was a mile long, included Custer, wearing a buckskin uniform, on his favorite bay thoroughbred at the head of ten Seventh Cavalry companies, followed by two companies of infantry, scouts, and guides. In all they were more than 1000 troops and one black woman, Sarah Campbell, the expedition’s  cook. The 110 canvas-topped wagons were pulled by six mule teams. In addition, they had horse-drawn Gatling guns and cannons, and three hundred head of cattle brought along to provide meat for the troops. The expedition even had a “Scientific corps” with them, which included a geologist and his assistant, a naturalist, a botanist, a medical officer, a topographical engineer, a zoologist, and a civilian engineer. Two miners, Horatio N. Ross and William T. McKay, were attached to the scientific corps. In addition, Custer brought a photographer, newspaper correspondents, the company’s band, hunting dogs, the son of US President Ulysses S. Grant, as well as his younger brothers, Tom and Boston. All to look for a site for a fort!!!

cook. The 110 canvas-topped wagons were pulled by six mule teams. In addition, they had horse-drawn Gatling guns and cannons, and three hundred head of cattle brought along to provide meat for the troops. The expedition even had a “Scientific corps” with them, which included a geologist and his assistant, a naturalist, a botanist, a medical officer, a topographical engineer, a zoologist, and a civilian engineer. Two miners, Horatio N. Ross and William T. McKay, were attached to the scientific corps. In addition, Custer brought a photographer, newspaper correspondents, the company’s band, hunting dogs, the son of US President Ulysses S. Grant, as well as his younger brothers, Tom and Boston. All to look for a site for a fort!!!

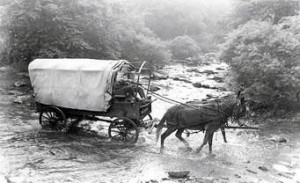

It was inevitable really…the migration of the people of the United States to the west coast, in search of gold, adventure, and more land. The east was filling up, and there was no place else to go, but west. Of course, many people would either not make it all the way to the West; choosing rather to homestead along the way, die, or actually make it to the West, and then return to the East. Nevertheless, before anyone could find out is life on the west coast suited them or not, they had to get to the west coast, and on May 16, 1842, the first major wagon train to the northwest departed from Elm Grove. Missouri, on the Oregon Trail. This was a little bit of a risky move, because US sovereignty over the Oregon Territory was not clearly established until 1846.

It was inevitable really…the migration of the people of the United States to the west coast, in search of gold, adventure, and more land. The east was filling up, and there was no place else to go, but west. Of course, many people would either not make it all the way to the West; choosing rather to homestead along the way, die, or actually make it to the West, and then return to the East. Nevertheless, before anyone could find out is life on the west coast suited them or not, they had to get to the west coast, and on May 16, 1842, the first major wagon train to the northwest departed from Elm Grove. Missouri, on the Oregon Trail. This was a little bit of a risky move, because US sovereignty over the Oregon Territory was not clearly established until 1846.

Nevertheless, American fur trappers and missionary groups had been living in the region for decades, along with Indians who had settled the land centuries earlier. Of course, everyone out there had a story to tell, and there were dozens of books and lectures that proclaimed Oregon’s agricultural potential. You can’t tell a story without creating interest somewhere. Even a boring story is of interest to someone, and this was no boring story. With the books and lectures coming out of the West, the white American farmers were very interested. They saw a chance to make their fortune, or at least to become independent. The actual first overland immigrants to Oregon, intended to farm primarily. A small band of 70 pioneers left Independence, Missouri in 1841. The stories they had heard from the fur traders brought them along the same route the traders had blazed, taking them west along the Platte River through the Rocky Mountains via the easy South Pass in Wyoming and then northwest to the Columbia River…basically through some on my own stomping grounds. Eventually, the trail they took was renamed by the pioneers, who called it the Oregon Trail.

The migration, once started, had little chance of being stopped, and in 1842, a slightly larger group of 100 pioneers made the 2,000-mile journey to Oregon. With the success of these two groups, the inevitable happened, accelerated in a major way by the severe depression in the Midwest, combined with a flood of propaganda from fur traders, missionaries, and government officials extolling the virtues of the land. They may have had good intentions, but it is never a good idea to lie to the public. With the disinformation on their minds, farmers dissatisfied with their prospects in Ohio, Illinois, Kentucky, and Tennessee, hoped to find better lives in the supposed paradise of Oregon. With that another type of “rush” began. Much like the “gold rush” years, the farmers saw the land as their “gold” and headed west.

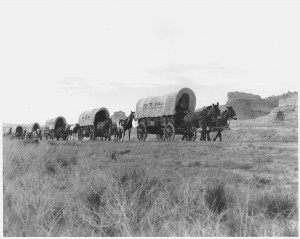

So, on this day in 1843, approximately 1,000 men, women, and children climbed aboard their wagons and steered their horses west out of the small town of Elm Grove, Missouri. It was the first real wagon train, comprised of more than 100 wagons with a herd of 5,000 oxen and cattle trailing behind. The train was led by Dr Elijah White, a Presbyterian missionary who had made the trip the year before. At first the trail was fairly easy, traveling over the flat lands of the Great Plains. There weren’t many obstacles in that area, and few river crossings, some of which could be dangerous for wagons. The bigger risk in the early days was the danger of Indian attacks, but they were still few and far between…at first anyway. The wagons were drawn into a circle at night to give the pioneers better protection from any attack that might come. They were very afraid of the Indians, who were enough different that they seemed deadly…to the pioneers anyway, and the Indians fear the White Man because of their weapons, and they were angry because the White Man wanted the land. In reality, the pioneers were far more in danger from seemingly mundane causes, like the accidental discharge of firearms, falling off mules or horses, drowning in river crossings, and disease. The trail became much more difficult, with steep ascents and descents over rocky terrain, after the train entered the mountains. The pioneers risked injury from overturned and runaway wagons.

Nevertheless, the wagon trains persevered, and the migrant movement continued until the West was populated. As for the 1,000-person party that made that original journey way back in 1843…the vast majority survived to reach their destination in the fertile, well-watered land of western Oregon. The next migration, in

1844 was smaller than that of the previous season, but in 1845 it jumped to nearly 3,000. Migration to the West was here to stay and the trains became an annual event, although the practice of traveling in giant convoys of wagons soon changed to many smaller bands of one or two-dozen wagons. The wagon trains really became a thing of the past in 1884, when the Union Pacific constructed a railway along the route.

1844 was smaller than that of the previous season, but in 1845 it jumped to nearly 3,000. Migration to the West was here to stay and the trains became an annual event, although the practice of traveling in giant convoys of wagons soon changed to many smaller bands of one or two-dozen wagons. The wagon trains really became a thing of the past in 1884, when the Union Pacific constructed a railway along the route.

The job of marking out the boundaries of a property, much less an entire nation, while maybe not a complicated job, a big job, nevertheless. The 19th century surveyors were charged with the job of mapping out the entire United States, and to me, that is a huge undertaking. These men were more than just surveyors. These men were the unheralded vanguards of the Old West. They established original geographical boundaries and retraced and identified existing borders in accordance with legal descriptions. It is said that they were part-astronomers, part-geologists, part-engineers, and these mapmakers were also arbitrators when land lines were in dispute. Several wars, and many smaller feuds have been fought and people killed over boundary disputes, and sometimes the surveyor had to be called in to settle the matter.

The job of marking out the boundaries of a property, much less an entire nation, while maybe not a complicated job, a big job, nevertheless. The 19th century surveyors were charged with the job of mapping out the entire United States, and to me, that is a huge undertaking. These men were more than just surveyors. These men were the unheralded vanguards of the Old West. They established original geographical boundaries and retraced and identified existing borders in accordance with legal descriptions. It is said that they were part-astronomers, part-geologists, part-engineers, and these mapmakers were also arbitrators when land lines were in dispute. Several wars, and many smaller feuds have been fought and people killed over boundary disputes, and sometimes the surveyor had to be called in to settle the matter.

Some famous men that we all know started out as surveyors. Men like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and Daniel Boone When these men were surveyors, actually risked their lives in the line of duty to map what ultimately became the passes, railroads, towns, dams and other structures that helped form the backbone of the West.

Surveyors were the ones who shaped Western history. Their endurance, sense of adventure, and knowledge of precision tools and mathematical principles became the tools of their trade. In fact, they really became Jocks of all trades. While surveying the many miles of the United States, the had to actually blaze trails, so they had to become woodsman, so they could get through some areas to even begin surveying the borders. They became experts in the science of soil management and crop production. As agronomists they worried that hot weather, combined with dry conditions, can hamper pollination. They had to understand the soil and botany. They had to find their food in the wild, because there weren’t any stores in the rugged, wilderness they were mapping.

It was a hard job, and there were many risks, but these men were strong-willed, and determined…and sometimes their lives were on the line. In 1838, came one of the first incidence of a surveyor being killed. It happened just two years after the Battle of San Jacinto…a battle in which the Texians defeated Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna. While surveying on the Guadalupe River north of San Antonio, Indians attacked a survey party and killed nine of the crew, including one surveyor who managed to carve his name, “Beatty,” on a tree before he died. At least seven more survey parties were attacked that spring and summer, from the Rio Frio to the Red Sometimes River.

The surveyors were essential when the railroad was being built. The surveyors were the ones who marked out  that track lines. They had to make sure they were not overtaking the landowners’ boundaries. The Indians were the main people to fight the surveyors, because they could see more and more of their land being confiscated. What would eventually be good, even for them, was seen as theft to them, and maybe it was, but when we look to the future, it’s easy to see that the land was going be essential to the people of the United States down the road. Nevertheless, the surveyors faced many dangers and really also had to be soldiers, because they were often in a fight for their lives, as they did their work. Surveyors were, and still are, essential to the ever-changing boundry lines in our nation, but that doesn’t make their job an easy one.

that track lines. They had to make sure they were not overtaking the landowners’ boundaries. The Indians were the main people to fight the surveyors, because they could see more and more of their land being confiscated. What would eventually be good, even for them, was seen as theft to them, and maybe it was, but when we look to the future, it’s easy to see that the land was going be essential to the people of the United States down the road. Nevertheless, the surveyors faced many dangers and really also had to be soldiers, because they were often in a fight for their lives, as they did their work. Surveyors were, and still are, essential to the ever-changing boundry lines in our nation, but that doesn’t make their job an easy one.

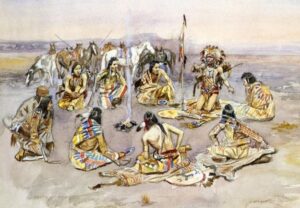

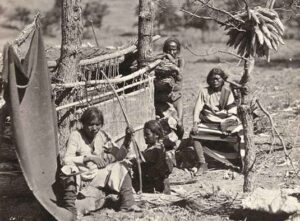

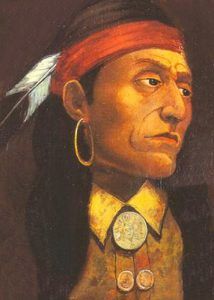

When the White Man came to this country, little was known about how the Indians lived or the things they used to make their lives easier. These days, we have learned much about all that. Things like killing the buffalo and using pretty much every part of the animal for things like food, clothing, weapons, and probably much more. They were also artists, to a degree that we can only imagine. They drew things and made things…from next to nothing…and as we know now, they were very good artists, especially with weaving. Once the Indians found out how much the white colonists liked their weaving, they began to make blankets and rugs to trade for other goods. Before then, the weaving was only used to make clothing for the tribe.

When the White Man came to this country, little was known about how the Indians lived or the things they used to make their lives easier. These days, we have learned much about all that. Things like killing the buffalo and using pretty much every part of the animal for things like food, clothing, weapons, and probably much more. They were also artists, to a degree that we can only imagine. They drew things and made things…from next to nothing…and as we know now, they were very good artists, especially with weaving. Once the Indians found out how much the white colonists liked their weaving, they began to make blankets and rugs to trade for other goods. Before then, the weaving was only used to make clothing for the tribe.

The Navajo people learned the how to build looms and weave fabrics from the Hopi Indians. This new “business venture” brought about a sedentary life as they spent long hours sitting and weaving. They soon learned to make beautiful blankets with geometric shapes, diamonds, and zig-zag patterns. Navajo rugs and blankets are almost exclusively produced by Navajo people of the Four Corners area of the United States. They have been highly sought after, for their beautiful craftsmanship for over 150 years.

The weavings of the Navajo people soon became a commercial production in the Four Corners area. I have

been there and seen them myself. It was very interesting. These days, it is all a part of the tourism industries. As one expert expresses it, “Classic Navajo serapes at their finest equal the delicacy and sophistication of any pre-mechanical loom-woven textile in the world.” Some old-world crafts really can’t be improved upon by using modern-day equipment. The old ways are simply the best ways, sometimes.

been there and seen them myself. It was very interesting. These days, it is all a part of the tourism industries. As one expert expresses it, “Classic Navajo serapes at their finest equal the delicacy and sophistication of any pre-mechanical loom-woven textile in the world.” Some old-world crafts really can’t be improved upon by using modern-day equipment. The old ways are simply the best ways, sometimes.

The pilgrims were not the only people who did not like, or accept, British rule. When the French sold some of their territory to the British, the Indian tribes in these areas were not happy about the new regime. The French had more or less left them alone to do as they chose, and so they tended to live in relative peace, but the British were a different kind of rule, and the Indians felt that they were far less conciliatory than their predecessors. It wasn’t that the French and the Indians got along well, after all they had just ended the French and Indian Wars in the early 1760s. It was simply that the British were more demanding and less giving in the area of the Indian rights, than the French had been.

The pilgrims were not the only people who did not like, or accept, British rule. When the French sold some of their territory to the British, the Indian tribes in these areas were not happy about the new regime. The French had more or less left them alone to do as they chose, and so they tended to live in relative peace, but the British were a different kind of rule, and the Indians felt that they were far less conciliatory than their predecessors. It wasn’t that the French and the Indians got along well, after all they had just ended the French and Indian Wars in the early 1760s. It was simply that the British were more demanding and less giving in the area of the Indian rights, than the French had been.

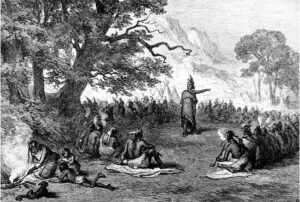

As the matter became more and more heated, an Ottawan Indian chief named Pontiac decided that it was time for the Indian tribes to rebel. So, he called together a confederacy of Native warriors to attack the British force at Detroit. In 1762, Pontiac enlisted support from practically every tribe from Lake Superior to the lower Mississippi for a joint campaign to expel the British from the formerly French-occupied lands. According to Pontiac’s plan, each tribe would seize the nearest fort and then join forces to wipe out the undefended settlements. In April 1763, Pontiac convened a war council on the banks of the Ecorse River near Detroit. It was decided that Pontiac and his warriors would gain access to the British fort at Detroit under the pretense of negotiating a peace treaty, giving them an opportunity to seize forcibly the arsenal there. However, British Major Henry Gladwin learned of the plot, and the British were ready when Pontiac arrived in early May 1763, and Pontiac was forced to begin a siege. His Indian allies in Pennsylvania began a siege of Fort Pitt, while other sympathetic tribes, such as the Delaware, the Shawnees, and the Seneca, prepared to move against various British forts and outposts in Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, at the same time. After failing to take the fort in their initial assault, Pontiac’s forces, made up of Ottawas and reinforced by Wyandots, Ojibwas and Potawatamis, initiated a siege that would stretch into months.

A British relief expedition attacked Pontiac’s camp on July 31, 1763. They suffered heavy losses and were repelled in the Battle of Bloody Run. However, they did succeeded in providing the fort at Detroit with reinforcements and supplies. That victorious battle allowed the fort to hold out against the Indians into the fall. Also holding on were the major forts at Pitt and Niagara, but the united tribes captured eight other fortified posts. At these forts, the garrisons were wiped out, relief expeditions were repulsed, and nearby frontier settlements were destroyed.

Two British armies were sent out in the spring of 1764. One was sent into Pennsylvania and Ohio under Colonel Bouquet, and the other to the Great Lakes under Colonel John Bradstreet. Bouquet’s campaign met with success, and the Delawares and the Shawnees were forced to sue for peace, breaking Pontiac’s alliance. Failing to persuade tribes in the West to join his rebellion, and lacking the hoped-for support from the French, Pontiac finally signed a treaty with the British in 1766. In 1769, he was murdered by a Peoria tribesman while visiting Illinois. His death led to bitter warfare among the tribes, and the Peorias were nearly wiped out.

Many people who love the era of the Cowboys and Indians, also find themselves intrigued by the Mountain Men. These men were the epitome of the “wild” west. The Mountain Men were often what many might call “social rejects,” because they lived in the wilderness, hunted and fished to sustain themselves, and were often trappers who sold their furs to supplement their living. All that seems rather normal, but they were also reclusive, and often had long hair and a bushy beard. I suppose that many people would think that our opinion of the mountain men was discriminatory, but we have always had some concerns over those who were so very different. Maybe we even associated the mountain men with lawlessness. They often lived in the wilderness, because the were non-conformists when it came to the law. It wasn’t that they wanted to rob banks and kill people, but rather that they wanted to be free to live their lives the way they saw fit, without all the rules and regulations of society.

Many people who love the era of the Cowboys and Indians, also find themselves intrigued by the Mountain Men. These men were the epitome of the “wild” west. The Mountain Men were often what many might call “social rejects,” because they lived in the wilderness, hunted and fished to sustain themselves, and were often trappers who sold their furs to supplement their living. All that seems rather normal, but they were also reclusive, and often had long hair and a bushy beard. I suppose that many people would think that our opinion of the mountain men was discriminatory, but we have always had some concerns over those who were so very different. Maybe we even associated the mountain men with lawlessness. They often lived in the wilderness, because the were non-conformists when it came to the law. It wasn’t that they wanted to rob banks and kill people, but rather that they wanted to be free to live their lives the way they saw fit, without all the rules and regulations of society.

One such mountain man, was Joe Meek, who was born in Virginia in 1810. Meek was a friendly and relentlessly good-humored young man. Unfortunately, Meek did not have a the same interest in school, that he did to be a friendly, funny guy. In reality, his biggest problem was that he had too much energy to sit still and learn. After finally giving up on schooling, at 16 years old, Meek moved west to join two of his brothers in Missouri. Meek later found a need to read and write, and so taught himself, but his spelling and grammar were said to be “highly original” throughout his life.

In early 1829, Meek joined William Sublette’s ambitious expedition to begin fur trading in the Far West. This was the perfect lifestyle for Meek, and he found himself flourishing. Meek traveled throughout the West for the next decade, thoroughly enjoying the adventure and independence of the mountain man life. Meek was an average man, standing 6 feet 2 inches tall. He wore a heavy beard, and became a favorite character at the annual mountain-men rendezvous, where he regaled his companions with humorous and often exaggerated stories of his wilderness adventures. Meek, who was a well known grizzly hunter, claimed he liked to “count coup” on the dangerous animals before killing them, a variation on a Native American practice in which they shamed a live human enemy by tapping them with a long stick. Meek also claimed to have wrestled an attacking grizzly with his bare hands, before finally sinking a tomahawk into its brain. I suppose it might have been a tall tale, but more than one mountain man hs fought a bear. Some have won, and some have not had the same outcome…sadly.

Meek may have been a misfit in society, but he had good relations with many Native Americans, and in fact, he married three Indian women during his lifetime, including the daughter of a Nez Perce chief. Still, that good relationship didn’t prevent him from getting into some squabbles with the tribes. Many of the Indians didn’t like the incursion of the mountain men into their territories, and periodically, things got hostile. In the spring of 1837, Meek was nearly killed by a Blackfeet warrior who was taking aim with his bow while Meek tried to reload his Hawken rifle. Luckily for Meek, the warrior dropped his first arrow while drawing the bow, and the mountain man had time to reload and shoot.

Finally, in 1840, Meek saw that the golden era of the free trappers was ending. He decided that it was time for a “career change.” Meek and another mountain man, along with Meek’s third wife guided one of the first wagon trains to cross the Rockies on the Oregon Trail. Once there, Meek settled in the lush Willamette Valley of western Oregon, became a farmer, and actively encouraged other Americans to join him. He could see that  times were changing. In 1847, Meek led a delegation to Washington DC, asking for military protection from Indian attacks and territorial status for Oregon. After the long journey, Meek arrived in Washington DC “ragged, dirty, and lousy.” Nevertheless, he became something of a celebrity in the capitol…maybe a little bit like “Crocodile Dundee.” Meek was a novelty, and the Easterners relished the boisterous good humor Meek showed in proclaiming himself the “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary from the Republic of Oregon to the Court of the United States.” The trip was quite successful, and Congress responded by making Oregon an official American territory and Meek became a US marshal.

times were changing. In 1847, Meek led a delegation to Washington DC, asking for military protection from Indian attacks and territorial status for Oregon. After the long journey, Meek arrived in Washington DC “ragged, dirty, and lousy.” Nevertheless, he became something of a celebrity in the capitol…maybe a little bit like “Crocodile Dundee.” Meek was a novelty, and the Easterners relished the boisterous good humor Meek showed in proclaiming himself the “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary from the Republic of Oregon to the Court of the United States.” The trip was quite successful, and Congress responded by making Oregon an official American territory and Meek became a US marshal.

Strangely, considering his anti-social beginnings, Meek returned to Oregon and became heavily involved in politics, eventually helping to found the Oregon Republican Party. He later retired to his farm, where he died on June 20, 1875 at the age of 65.

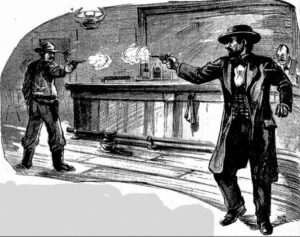

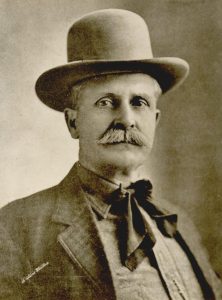

Unfortunately, there are among us, people who are corrupt and ruthless, and sometimes, things happen because of corruption, anger, or even stupidity. William Tilghman was born in Fort Dodge, Iowa on July 4, 1854, at the height of the “Wild West” era. He was a man who wanted something more, so at 16 years old, he moved west. As sometimes happened, men who went west, toyed with the wild life that was brought about by the lawless area. Tilghman was no different. He fell in with a bad crowd of young men who stole horses from the Indians. After several narrow escapes with angry Indians, Tilghman decided that rustling was too dangerous and settled in Dodge City, Kansas, where he briefly served as a deputy marshal before opening a saloon. He was arrested twice for alleged train robbery and rustling, but the charges did not stick. It was a shaky start, but Tilghman gradually built a reputation as an honest and respectable young man in Dodge City. Before long, he became the deputy sheriff of Ford County, Kansas. Later, he was offered and accepted the job of the marshal of Dodge City…a real life Matt Dillon, from Gunsmoke.

Unfortunately, there are among us, people who are corrupt and ruthless, and sometimes, things happen because of corruption, anger, or even stupidity. William Tilghman was born in Fort Dodge, Iowa on July 4, 1854, at the height of the “Wild West” era. He was a man who wanted something more, so at 16 years old, he moved west. As sometimes happened, men who went west, toyed with the wild life that was brought about by the lawless area. Tilghman was no different. He fell in with a bad crowd of young men who stole horses from the Indians. After several narrow escapes with angry Indians, Tilghman decided that rustling was too dangerous and settled in Dodge City, Kansas, where he briefly served as a deputy marshal before opening a saloon. He was arrested twice for alleged train robbery and rustling, but the charges did not stick. It was a shaky start, but Tilghman gradually built a reputation as an honest and respectable young man in Dodge City. Before long, he became the deputy sheriff of Ford County, Kansas. Later, he was offered and accepted the job of the marshal of Dodge City…a real life Matt Dillon, from Gunsmoke.

Tilghman was one of the first men into the territory when Oklahoma opened to settlement in 1889, and he became a deputy US marshal for the region in 1891. In the late 19th century, lawlessness was still very much a part of Oklahoma. Tilghman helped to bring order the to area by ridding Oklahoma by capturing some of the most notorious bandits of the day. While locking up many criminals, Tilghman, nevertheless, managed to earn a well-deserved reputation for treating even the worst criminals fairly and protecting the rights of the unjustly accused. Any man, who found himself in Tilghman’s custody, knew he was safe from angry vigilante mobs,  because Tilghman had little tolerance for those who took the law into their own hands. In 1898, a wild mob lynched two young Indians who were falsely accused of raping and murdering a white woman. Tilghman arrested and secured prison terms for eight of the mob leaders and captured the real rapist-murderer.

because Tilghman had little tolerance for those who took the law into their own hands. In 1898, a wild mob lynched two young Indians who were falsely accused of raping and murdering a white woman. Tilghman arrested and secured prison terms for eight of the mob leaders and captured the real rapist-murderer.

In 1924, after serving a term as an Oklahoma state legislator, making a movie about his frontier days, and serving as the police chief of Oklahoma City, Tilghman might well have been expected to quietly retire. However, it was the height of the Prohibition era, and the old lawman was unable to hang up his gun. He still felt a calling to keep law and order in his town. He accepted a job as city marshal in Cromwell, Oklahoma. On November 1, 1924, William Tilghman, who was known to both friends and enemies alike as “Uncle Billy” was murdered by a corrupt prohibition agent who resented Tilghman’s refusal to ignore local bootlegging operations. The Prohibition officer was drunk, and in his anger, made the worst mistake of his life.

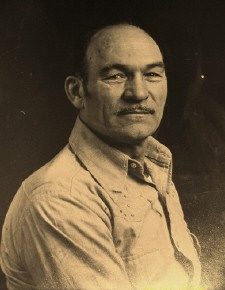

My great grandfather, Cornelius Byer was a kind and a fair man. He was generous and honest. It was these qualities that earned him the respect of the Indian tribes in the Gordon, Nebraska area. Great Grandpa passed away on October 23, 1930, but the celebration of life, really began before the day of the funeral, and even before he passed away. Over the years of his life, my great grandfather became a great friend of the Indians. He was invited to their pow wows, he was asked his opinions on things…and they listened when he spoke. He was helpful to the Indian tribes, and they, in turn treated him with great respect.

My great grandfather, Cornelius Byer was a kind and a fair man. He was generous and honest. It was these qualities that earned him the respect of the Indian tribes in the Gordon, Nebraska area. Great Grandpa passed away on October 23, 1930, but the celebration of life, really began before the day of the funeral, and even before he passed away. Over the years of his life, my great grandfather became a great friend of the Indians. He was invited to their pow wows, he was asked his opinions on things…and they listened when he spoke. He was helpful to the Indian tribes, and they, in turn treated him with great respect.

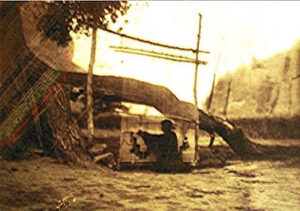

The Indians would often show up at his home…something that would most likely panic most people. Most often the women and children would stay outside, while the men went in to visit with Great Grandpa. It was another show of respect. The Indians often camped near the house when the men were visiting. I’m sure it was a very interesting lifestyle for my grandmother.

While all that was interesting, probably the most interesting thing happened as Great Grandpa was dying and after his passing. When he lay dying, the Indians came…long lines of them. Each one, including the women and

children, passed by his bed. They spoke words of respect and admiration. I’m sure it took hours, but none were turned away. Great Grandma knew how much they loved him, and how much they needed to say goodbye. I would love to have had the chance to see that scene. These were two groups of people who normally didn’t get along, and yet they showed so much love and respect for one another. There was no warring with, no stealing from, no depriving of one another. There was simply love and respect. I’m sure it made my Great Grandmother Edna (Fishburn) Byer and their children feel very safe over the years.

children, passed by his bed. They spoke words of respect and admiration. I’m sure it took hours, but none were turned away. Great Grandma knew how much they loved him, and how much they needed to say goodbye. I would love to have had the chance to see that scene. These were two groups of people who normally didn’t get along, and yet they showed so much love and respect for one another. There was no warring with, no stealing from, no depriving of one another. There was simply love and respect. I’m sure it made my Great Grandmother Edna (Fishburn) Byer and their children feel very safe over the years.

My grandfather, George Byer arrived at the homestead on October 20, 1930. My grandmother, Hattie Byer stayed home with their newborn daughter, Virginia, who was just 4 months old at the time. Grandpa brought almost 2 year old Evelyn with him. His letter at the time said that all the children were there, or soon would be. Three days later, Great Grandpa Cornelius Byer passed away. I’m so glad my grandpa got to see his dad before he passed. When it was time to have the funeral, they would have to travel into Gordon, Nebraska. We would never think of transporting our own loved one to the funeral, but those were different times. Nevertheless, the

Indians would not leave their dear friend to go alone. With the casket in a wagon, and his son driving, Great Grandpa went to his funeral. Little Evelyn sat in the back of the wagon, wide-eyed in wonder as a long line of Indians followed the procession to the cemetery. In death, as in life, their respect for this man, who was my great grandfather, was on display. I can’t think of a greater honor than this. Cornelius Byer was truly loved and respected by all who knew him.

Indians would not leave their dear friend to go alone. With the casket in a wagon, and his son driving, Great Grandpa went to his funeral. Little Evelyn sat in the back of the wagon, wide-eyed in wonder as a long line of Indians followed the procession to the cemetery. In death, as in life, their respect for this man, who was my great grandfather, was on display. I can’t think of a greater honor than this. Cornelius Byer was truly loved and respected by all who knew him.