gunpowder

Most of us think of dogs as pets, and so they are, but they are so much more. Dogs know when their master is sick, lonely, or worried. Dogs ask little of their masters, and give so much back, but there is a group of dogs who are working dogs. In fact, we often see dogs in everyday life and think little of their presence, when in fact, their work is vital to those they work for. One of the most well known working dog groups is the K-9 Units. We think of these dogs as police dogs, and so they are, but originally, the K-9 Corps were founded in World War II. Of course, dogs were used long before that war, but not in the capacity of World War II.

Most of us think of dogs as pets, and so they are, but they are so much more. Dogs know when their master is sick, lonely, or worried. Dogs ask little of their masters, and give so much back, but there is a group of dogs who are working dogs. In fact, we often see dogs in everyday life and think little of their presence, when in fact, their work is vital to those they work for. One of the most well known working dog groups is the K-9 Units. We think of these dogs as police dogs, and so they are, but originally, the K-9 Corps were founded in World War II. Of course, dogs were used long before that war, but not in the capacity of World War II.

The Romans used dogs in battles, sending them in to attack the enemy. Native Americans used them as pack animals, as well as sentry animals. Even in the Middle Ages, dogs were sent into battle equipped with their own armor. Modern European societies had long established traditions of using dogs in war. But, I think that their use was probably made most famous 77 years ago, when in January of 1942, Dogs for Defense, Inc. was established as a national organization to help procure dogs for war training purposes. Although some dogs were acquired through purchase, it was largely through the dog owner population’s patriotic sentiments that most dogs were acquired for training. That really amazes me. I understand patriotism, and how people would volunteer in the service, but it seems strange to me to volunteer your dog.  Nevertheless, they did. It was the job of Dogs For Defense not only to procure the dogs, but also to train them. Once trained, the dogs were to be given to the Quartermaster General, who then turned them over to the Plant Protection Branch and Inspection Division. Many thought the primary use of dogs would be as sentries for civilian war plants and quartermaster depot, but dogs have proven to be a much more.

Nevertheless, they did. It was the job of Dogs For Defense not only to procure the dogs, but also to train them. Once trained, the dogs were to be given to the Quartermaster General, who then turned them over to the Plant Protection Branch and Inspection Division. Many thought the primary use of dogs would be as sentries for civilian war plants and quartermaster depot, but dogs have proven to be a much more.

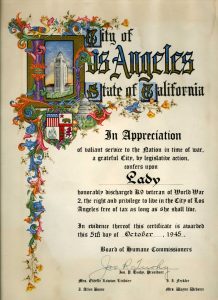

There are dogs that can sniff out drugs, gun powder…and the enemy. The DFD trained over 10,000 dogs. Most of the dogs were used at home for sentry duty, however, more than 1,800 dogs were sent into combat starting in 1942. The US Marine Corps sent over 1,000 dogs to be trained at their Camp Lejeune facility. Unfortunately, many commanders were unfamiliar, and maybe a little distrusting of the dogs, and didn’t know how to use them to their advantage. Seven Quartermaster Corps War Dog Platoons were sent to the European Theatre of Operations, but they did not have much success, probably due mostly to the lack of training with their handlers. In 1943, the QMC sent a detachment of six scout dogs and two messenger dogs to operate in the  Pacific Theatre. This was a test of their value in combat conditions. The Japanese troops had deeply entrenched themselves on many islands in the Pacific theater of operations. Thousands were hiding in caves and in the dense jungles. They would lie very still, in wait for patrolling Marines and soldiers and then ambush them before the troops ever detected enemy forces. This is where the dogs proved their value. The first war dog platoons took to the Pacific island of New Britain. Here Marine war dogs attached to the Sixth Army first worked on sentry duty. Once a beachhead was established the dogs and handlers began conducting their patrols. They went on forty-eight patrols in fifty-three days. The dog patrols captured or killed 200 Japanese soldiers. This early success of war dog platoons set the standard for what could be expected, and what could not, from a K-9 detachment. I think that the more training given to both dogs and handlers, the better the results will be, as we have seen in K-9 police dogs in modern times.

Pacific Theatre. This was a test of their value in combat conditions. The Japanese troops had deeply entrenched themselves on many islands in the Pacific theater of operations. Thousands were hiding in caves and in the dense jungles. They would lie very still, in wait for patrolling Marines and soldiers and then ambush them before the troops ever detected enemy forces. This is where the dogs proved their value. The first war dog platoons took to the Pacific island of New Britain. Here Marine war dogs attached to the Sixth Army first worked on sentry duty. Once a beachhead was established the dogs and handlers began conducting their patrols. They went on forty-eight patrols in fifty-three days. The dog patrols captured or killed 200 Japanese soldiers. This early success of war dog platoons set the standard for what could be expected, and what could not, from a K-9 detachment. I think that the more training given to both dogs and handlers, the better the results will be, as we have seen in K-9 police dogs in modern times.

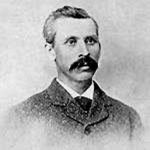

Shortly after President Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase from France, which made it an American territory, William Ashley, who was a Virginia native, made the decision to move to Missouri. Ashley was a young man, who was looking to make a name for himself. He entered into a partnership with Andrew Henry to manufacture gunpowder and lead. Opportunists, Ashley and Henry took advantage of the fact that these two commodities were in short supply in young America.

Shortly after President Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase from France, which made it an American territory, William Ashley, who was a Virginia native, made the decision to move to Missouri. Ashley was a young man, who was looking to make a name for himself. He entered into a partnership with Andrew Henry to manufacture gunpowder and lead. Opportunists, Ashley and Henry took advantage of the fact that these two commodities were in short supply in young America.

Ashley’s business prospered during the War of 1812, and he also joined the Missouri militia. He eventually achieved the rank of general. When Missouri became a state in 1822, Ashley used his military fame, and his business success to win election at lieutenant governor. Once elected, Ashley set about looking for opportunities to enrich both Missouri and his own pocketbook. Because he knew the area, he realized that Saint Louis was in a perfect place to exploit the fur trade on the upper Missouri River.

Ashley recruited his old business partner, Henry to join him in this new venture. Then, Ashley placed an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette and Public Advisor seeking 100 “enterprising young men” to engage in fur trading on the Upper Missouri. The advertisement was a big success. Scores of young men responded and came to Saint Louis. Among them were such future legendary mountain men as Jedediah Smith and Jim Bridger, as well as the famous river man Mike Fink. In time, these men and dozens of others would go on to uncover many of the geographic mysteries of the Far West, but for now they were looking to make a living trapping animals for their furs.

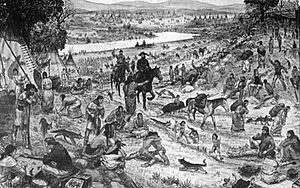

1822 found Ashley and a small band of his fur trappers building a trading post on the Yellowstone River in Montana in order to expand outward from the Missouri River. The Arikara Indians didn’t like this invasion, and they were deeply hostile to Ashley’s attempts to undercut their long-standing position as middlemen in the fur trade. The ensuing attacks eventually forced the men to abandon the Yellowstone post. Out of desperation, Ashley hit on a new strategy. Instead of building central permanent forts along the major rivers, he decided to send his trappers overland in small groups traveling by horseback. By avoiding the river arteries, the trappers could both escape detection by hostile Indians and develop new and untapped fur regions. Almost by accident, Ashley invented the famous “rendezvous” system that revolutionized the American fur trade. The necessary supplies were delivered and furs were delivered at meetings in a large meadow near the Henry’s Fork of Wyoming’s Green River in the early summer of 1825.

Ashley’s first fur trapper rendezvous was very successful. Ashley took home a tidy profit for his efforts. The fur  trappers not only had an opportunity to trade for supplies, but a chance to enjoy a few weeks of often drunken socializing. Ashley organized a second highly profitable rendezvous in 1826, and then decided to sell out. While he was no longer a part of it, his rendezvous system continued to be used by others. The system eventually became the foundation for the powerful Rocky Mountain Fur Company. With plenty of money in the bank, Ashley was able to return to his first love…politics. He was elected to Congress three times and once to the Senate, where he helped further the interests of the western land that had made him rich.

trappers not only had an opportunity to trade for supplies, but a chance to enjoy a few weeks of often drunken socializing. Ashley organized a second highly profitable rendezvous in 1826, and then decided to sell out. While he was no longer a part of it, his rendezvous system continued to be used by others. The system eventually became the foundation for the powerful Rocky Mountain Fur Company. With plenty of money in the bank, Ashley was able to return to his first love…politics. He was elected to Congress three times and once to the Senate, where he helped further the interests of the western land that had made him rich.