foam

Thankfully, the NASA space program hasn’t had a great number of losses, but that doesn’t make any loss less devastating that any of the others. On February 1, 2003, just a little over 17 years after the Challenger disaster, the country was once again feeling like the Space Shuttle program was so safe that it was even mundane. Many people had no idea when the shuttle flights went up or came down. It wasn’t the nation’s fault, it’s just that like air travel, the Shuttle program was relatively save, but when disaster strikes, we are once again reminded…horrifically, that relatively save does not mean completely safe from an accident. People are prone to get comfortable when things are going well. We forget the bad times. Nevertheless, space travel is not accident proof, even if it has become relatively safe.

Thankfully, the NASA space program hasn’t had a great number of losses, but that doesn’t make any loss less devastating that any of the others. On February 1, 2003, just a little over 17 years after the Challenger disaster, the country was once again feeling like the Space Shuttle program was so safe that it was even mundane. Many people had no idea when the shuttle flights went up or came down. It wasn’t the nation’s fault, it’s just that like air travel, the Shuttle program was relatively save, but when disaster strikes, we are once again reminded…horrifically, that relatively save does not mean completely safe from an accident. People are prone to get comfortable when things are going well. We forget the bad times. Nevertheless, space travel is not accident proof, even if it has become relatively safe.

On that awful February 1st morning in 2003, we were once again jolted out of our comfort zones and thrust  back into the reality that the Shuttle program might have some serious flaws. Still, the Space Shuttle program was a long running and highly successful program, running from 1981 to 2011. During the course of the program, a total of 135 missions were flown, all launched from Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. During that period of time, the fleet logged 1,322 days, 19 hours, 21 minutes and 23 seconds of flight time. The first orbiter built, Enterprise, was used for atmospheric flight tests (ALT) but future plans to upgrade it to orbital capability were ultimately canceled. Originally, NASA built four fully operational orbiters…Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis. Of course, we know that Challenger and Columbia were destroyed in mission accidents in 1986 and 2003 respectively, killing a total of fourteen astronauts. A fifth operational orbiter, Endeavour, was built in 1991 to replace Challenger. In the end, it was decided that the shuttles were getting old and had too many flaws, so the Space Shuttle was retired from service upon the conclusion of STS-135 by Atlantis on July 21, 2011.

back into the reality that the Shuttle program might have some serious flaws. Still, the Space Shuttle program was a long running and highly successful program, running from 1981 to 2011. During the course of the program, a total of 135 missions were flown, all launched from Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. During that period of time, the fleet logged 1,322 days, 19 hours, 21 minutes and 23 seconds of flight time. The first orbiter built, Enterprise, was used for atmospheric flight tests (ALT) but future plans to upgrade it to orbital capability were ultimately canceled. Originally, NASA built four fully operational orbiters…Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis. Of course, we know that Challenger and Columbia were destroyed in mission accidents in 1986 and 2003 respectively, killing a total of fourteen astronauts. A fifth operational orbiter, Endeavour, was built in 1991 to replace Challenger. In the end, it was decided that the shuttles were getting old and had too many flaws, so the Space Shuttle was retired from service upon the conclusion of STS-135 by Atlantis on July 21, 2011.

It was a piece of foam insulation that would bring down the Columbia shuttle. It broke off and hit the leading edge of the wing. That small little bit of damage to the wing allowed hot gases to enter the wing causing it to  break up as the craft entered Earth’s atmosphere. During the breakup, debris and the bodies of the astronauts were strewn across the state of Texas. The breakup began over California at 8:53am, and by 8:59am, communication was lost. Mission Control began its disaster procedures at 9:12am. Lost in the disaster were Rick D Husband (Commander), William C McCool (Pilot), Michael P Anderson (Payload Commander), Ilan Ramon (Payload Specialist), Kalpana Chawla (an Indian-born aerospace engineer and a Mission Specialist), David M Brown (Mission Specialist), and Laurel Blair Salton Clark (Mission Specialist). Today, marks the 20th anniversary of that fateful day. Today, we honor those we lost.

break up as the craft entered Earth’s atmosphere. During the breakup, debris and the bodies of the astronauts were strewn across the state of Texas. The breakup began over California at 8:53am, and by 8:59am, communication was lost. Mission Control began its disaster procedures at 9:12am. Lost in the disaster were Rick D Husband (Commander), William C McCool (Pilot), Michael P Anderson (Payload Commander), Ilan Ramon (Payload Specialist), Kalpana Chawla (an Indian-born aerospace engineer and a Mission Specialist), David M Brown (Mission Specialist), and Laurel Blair Salton Clark (Mission Specialist). Today, marks the 20th anniversary of that fateful day. Today, we honor those we lost.

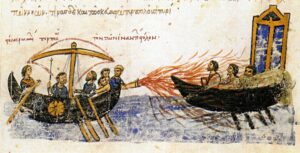

We seldom, if ever, think of a flamethrower as a weapon of warfare, but in the year 672, it was very much the weapon of choice for naval warfare by the the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantines). The weapon called Greek Fire was used in ship-mounted flamethrowers. This weapon was so unique and deadly due to the fact that throwing water onto the solution would only feed the fire. That really left nothing to do but abandon ship and try to swim as far away as you could and as fast as you could. Imagine the shock as the first victim of this weapon tried to throw water on the flames, only to have them explode in their faces. These days, Firefighters understand that some chemical fires require a different form of attack than other chemical fires. It the case of something like the Greek Fire, used by the Eastern Roman Empire, modern firefighters would use a foam solution or a dry powder, usually found in a fire extinguisher. Unfortunately, those things were not available in 672.

We seldom, if ever, think of a flamethrower as a weapon of warfare, but in the year 672, it was very much the weapon of choice for naval warfare by the the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantines). The weapon called Greek Fire was used in ship-mounted flamethrowers. This weapon was so unique and deadly due to the fact that throwing water onto the solution would only feed the fire. That really left nothing to do but abandon ship and try to swim as far away as you could and as fast as you could. Imagine the shock as the first victim of this weapon tried to throw water on the flames, only to have them explode in their faces. These days, Firefighters understand that some chemical fires require a different form of attack than other chemical fires. It the case of something like the Greek Fire, used by the Eastern Roman Empire, modern firefighters would use a foam solution or a dry powder, usually found in a fire extinguisher. Unfortunately, those things were not available in 672.

The Greek Fire was mostly used in naval warfare, because the required large flamethrowers to send its projectile across the water to the enemy ships. Ships could be better accommodated such a large piece of equipment. The infantry would be unable to carry such a weapon, although they probably wished they could, as it would effectively annihilate the enemy. The Greek Fire consisted of a combustible compound emitted by a flame-throwing weapon. It is believed that it could be ignited on contact with water, and was probably based on naphtha and quicklime. The Byzantines typically used the Greek Fire in naval battles with great results, as it could supposedly continue burning while floating on water. This technological advantage provided the Byzantines with military victories, including the salvation of Constantinople during the first and second Arab sieges. The Empire couldn’t have survived without it.

The impression made by Greek fire on the western European Crusaders was such that the name was applied to  any sort of incendiary weapon, including those used by Arabs, the Chinese, and the Mongols, even though the formulas were different from that of Byzantine Greek Fire, which was a closely guarded state secret. The Byzantines also used pressurized nozzles to project the liquid onto the enemy, in a manner resembling a modern flamethrower. The usage of the term Greek fire has even been general in English and most other languages since the Crusades. The solution had a number of other names over the centuries. including sea fire, Roman fire, war fire, liquid fire, sticky fire, or manufactured fire, but none stuck quite like Greek Fire.

any sort of incendiary weapon, including those used by Arabs, the Chinese, and the Mongols, even though the formulas were different from that of Byzantine Greek Fire, which was a closely guarded state secret. The Byzantines also used pressurized nozzles to project the liquid onto the enemy, in a manner resembling a modern flamethrower. The usage of the term Greek fire has even been general in English and most other languages since the Crusades. The solution had a number of other names over the centuries. including sea fire, Roman fire, war fire, liquid fire, sticky fire, or manufactured fire, but none stuck quite like Greek Fire.