english

If you travel to a different area of the country or even other English-speaking areas of the world, you will find that here are different accents and even that words are used differently. Still, just because you are visiting or move to those places, doesn’t mean that you will immediately take on those accents, or their use of words. Nevertheless, when you move to a different region, your use of the language does immediately begin to evolve, whether you realize it or not, and whether it is intentional or not. The first Englishmen to set foot on American soil with the intent to colonize the land were no exception. The language began to evolve almost immediately….and it remains a fluid, almost living process to this day. “Americanisms” have been created or changed from other English terms to produce a language that very much differs from our forefathers, signifying our uniqueness and independence.

If you travel to a different area of the country or even other English-speaking areas of the world, you will find that here are different accents and even that words are used differently. Still, just because you are visiting or move to those places, doesn’t mean that you will immediately take on those accents, or their use of words. Nevertheless, when you move to a different region, your use of the language does immediately begin to evolve, whether you realize it or not, and whether it is intentional or not. The first Englishmen to set foot on American soil with the intent to colonize the land were no exception. The language began to evolve almost immediately….and it remains a fluid, almost living process to this day. “Americanisms” have been created or changed from other English terms to produce a language that very much differs from our forefathers, signifying our uniqueness and independence.

Of course, the people didn’t notice the changes right away, but by 1720, the English colonists began to notice that their language was quite different from that spoken in their Motherland. I’m sure they wondered just how that came to be? Basically, when you hear new “slang” words, and people don’t hear the accents spoken as well, the whole dynamic of the language changes. Also, very formal words like “thee, thou, and such” might become too cumbersome and so they are discarded. Everyone in the colonies knew that English would be our native language by 1790, because when the United States took its first census, there were four million Americans, 90% of whom were descendants of English colonists. So, it made perfect sense.

Nevertheless, it would not be the same as that spoken in Great Britain. The reasons are varied, but the most obvious reason was the sheer distance from England. The main way the language evolved was that over the years, many words were borrowed from the Native Americans, as well as other immigrants from France, Germany, Spain, and other countries. In addition, words that became obsolete “across the pond” continued to be utilized in the colonies. In other cases, words simply had to be created in order to explain the unfamiliar landscape, weather, animals, plants, and living conditions that these early pioneers encountered. By 1790 it was obvious that American English would be a very different language that British English.

The first “official” reference to the “American dialect” was made in 1756 by Samuel Johnson, a year after he published his Dictionary of the English Language. Johnson’s use of the term “American dialect” was not meant to simply explain the differences but rather, was intended as an insult. This “new” language was called “barbarous” and referred to our “Americanisms” as barbarisms. Because of the dissention between England and the Colonies, the British sneering at our language continued for more than a century after the Revolutionary War. They laughed and condemned as unnecessary, hundreds of American terms and phrases, but to our newly independent Americans, they were proud of their “new” American language and considered it to be another badge of independence. In 1789, Noah Webster wrote in his Dissertations on the English Language, “The reasons for American English being different than English English are simple…As an independent nation, our honor requires us to have a system of our own, in language as well as government.” In the eyes of the Colonists, that settled the matter, and when the United States was formed, the new nation was proud to be separated for the “Motherland” and would have it no other way.

Our leaders, including Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Rush, agreed — it was not only good politics, but it was also sensible. The most atrocious changes to the British were the heavy use of contractions such as ain’t, can’t, don’t, and couldn’t. The feelings of the “rest of the world” didn’t matter to Americans, and the language changed even more during the western movement as numerous Native American and Spanish words became an everyday part of our language. The evolution of the American language continued into the 20th century and really continues even to this day. After World War I, when Americans were in a patriotic and anti-foreign mood, the state of Illinois went so far as to pass an act making the official language of the state the “American language.” In 1923, in the State of Illinois General Assembly, they passed the act stating in part, “The official language of the State of Illinois shall be known hereafter as the ‘American’ language and not as the ‘English’

language. A similar bill was also introduced in the US House of Representatives the same year but died in committee. Ironically, after centuries of forming our ‘own’ language, the English and American versions are once again beginning to blend as movies, songs, electronics, and global traveling bring the two ‘languages’ closer together.”

language. A similar bill was also introduced in the US House of Representatives the same year but died in committee. Ironically, after centuries of forming our ‘own’ language, the English and American versions are once again beginning to blend as movies, songs, electronics, and global traveling bring the two ‘languages’ closer together.”

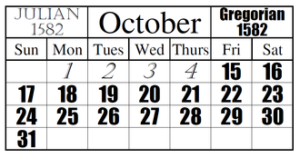

Some historians speculate that April Fools’ Day actually dates back to 1582, when France switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. This wasn’t a popular change with everyone, and some people just forgot it was going to happen. Nevertheless, the Council of Trent called for it to happen in 1563. Those who accepted the change and of course, the Council of Trent were not sympathetic to those who didn’t cooperate. People who were slow to get the news or failed to recognize that the start of the new year had moved to January 1 and continued to celebrate it during the last week of March through April 1 became the butt of jokes and hoaxes. I don’t suppose that first April Fools’ Day was so fun for the victims of the hoaxes in 1563. Those people were really being ridiculed.

Some historians speculate that April Fools’ Day actually dates back to 1582, when France switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. This wasn’t a popular change with everyone, and some people just forgot it was going to happen. Nevertheless, the Council of Trent called for it to happen in 1563. Those who accepted the change and of course, the Council of Trent were not sympathetic to those who didn’t cooperate. People who were slow to get the news or failed to recognize that the start of the new year had moved to January 1 and continued to celebrate it during the last week of March through April 1 became the butt of jokes and hoaxes. I don’t suppose that first April Fools’ Day was so fun for the victims of the hoaxes in 1563. Those people were really being ridiculed.

With such a start, to this unique day, April Fools’ Day seems like it was really a cruel day, not the fun day we know today. Nevertheless, the idea of jokes and pranks is one that a lot of people could get onboard with…it’s almost as good as a tickle torture to make people laugh. Yes, there is a victim, but it’s all in good fun. The  English agreed, and on April 1, 1700, it began. English pranksters collectively decided to make April Fools’ Day or All Fools’ Day, as it was also called, an annual tradition by playing practical jokes on each other. It has been celebrated for several centuries by different cultures now.

English agreed, and on April 1, 1700, it began. English pranksters collectively decided to make April Fools’ Day or All Fools’ Day, as it was also called, an annual tradition by playing practical jokes on each other. It has been celebrated for several centuries by different cultures now.

Favorite pranks included having paper fish placed on the victims’ backs and being referred to as poisson d’avril (April fish), said to symbolize a young, “easily hooked” fish…basically a gullible person. April Fools’ Day spread throughout Britain during the 18th century. In Scotland, the tradition became a two-day event, starting with “hunting the gowk” (gowk is a word for cuckoo bird, a symbol for fool), in which people were sent on phony errands and followed by Tailie Day, which involved pranks played on people’s derrieres, such as pinning fake tails or “kick me” signs on them. And I thought the pranks played these days were unique.

These days, lots of people get into the action. Everything from telling someone they had a spider in their hair to the really good pranksters, who can really get their victims going. My own family, when I was a kid growing up,

were dedicated pranksters. Things like switching the salt and sugar were a common prank, and even used on days other than April Fools’ Day. Of course, we tried things like a spider in your hair, a rip in your jeans, and such, but we were never mean about it. So, in the end, a day which was meant to really humiliate, has turned into a prankster’s holiday, and most people are good natured about it, and simply have a few great laughs. Happy April Fools’ Day everyone. Let the pranks begin and continue!!

were dedicated pranksters. Things like switching the salt and sugar were a common prank, and even used on days other than April Fools’ Day. Of course, we tried things like a spider in your hair, a rip in your jeans, and such, but we were never mean about it. So, in the end, a day which was meant to really humiliate, has turned into a prankster’s holiday, and most people are good natured about it, and simply have a few great laughs. Happy April Fools’ Day everyone. Let the pranks begin and continue!!

Animals have been used in most wars for different purposes. Some animals were messengers, like the carrier pigeon. Some were for warning, like the dog, which also served as a soldier in a fight situation. They are very loyal, and will do their best to save their master. These types of animals were to be expected to a degree, but during World War II, there was a certain cat, named Oscar, also known as Oskar, and ultimately known as Unsinkable Sam, because this cat managed not only to serve in both the Kriegsmarine, but also the Royal Navy. The cat’s original name is unknown, but the name “Oscar” was given by the crew of the British destroyer HMS Cossack, when that crew rescued him from the sea following the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. The name “Oscar” was given to the cat, and was derived from the International Code of Signals for the letter ‘O’ which is code for “Man Overboard” (the German spelling “Oskar” was sometimes used since he was a German cat). For Oscar to survive the sinking of the Bismarck was amazing, but it was not the end of his story.

Animals have been used in most wars for different purposes. Some animals were messengers, like the carrier pigeon. Some were for warning, like the dog, which also served as a soldier in a fight situation. They are very loyal, and will do their best to save their master. These types of animals were to be expected to a degree, but during World War II, there was a certain cat, named Oscar, also known as Oskar, and ultimately known as Unsinkable Sam, because this cat managed not only to serve in both the Kriegsmarine, but also the Royal Navy. The cat’s original name is unknown, but the name “Oscar” was given by the crew of the British destroyer HMS Cossack, when that crew rescued him from the sea following the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. The name “Oscar” was given to the cat, and was derived from the International Code of Signals for the letter ‘O’ which is code for “Man Overboard” (the German spelling “Oskar” was sometimes used since he was a German cat). For Oscar to survive the sinking of the Bismarck was amazing, but it was not the end of his story.

As you know, war is a tough time to be on a ship. There is no guarantee that the ship will make it through the war, and if a ship goes down in a battle, it usually takes some, if not all of the crew with it. A cat would usually have little chance of survival on a ship that is sinking, but someone forgot to tell Oskar that. Oskar was a black and white patched cat. It is thought that he was originally owned by one of the crewman of the German battleship Bismarck and was on board the ship on May 18, 1941 when the ship set sail on Operation Rheinübung (German for Rhine Exercise). It was the Bismarck’s only mission. On May 27, 1941, the Bismarck was sunk after a fierce sea-battle. The sinking took with it most of the crew. Out of a crew of 2,100 men, only 115 from her crew survived…and one cat. Hours after the sinking, Oscar was found floating on a board and picked from the water by the British destroyer HMS Cossack.

The crew of the Cossack decided that since Oscar was used to being on a ship, he could just stay with them. So, Oscar “served” on board Cossack for the next few months as the ship carried out convoy escort duties in the Mediterranean Sea and north Atlantic Ocean. On October 24, 1941, Cossack was escorting a convoy from Gibraltar to Great Britain when she was severely damaged by a torpedo fired by the German submarine U-563. The surviving crew were transferred to the destroyer HMS Legion, and an attempt was made to tow the badly listing Cossack back to Gibraltar. Unfortunately, the weather was not cooperative, and as it worsened, the task became impossible and had to be abandoned. On October 27, a day after the tow was slipped, Cossack sank to the west of Gibraltar. The initial explosion had blown off one third of the forward section of the ship, killing 159 of the crew, but Oscar survived, and was taken to Gibraltar. To say that a cat has nine lives is almost an understatement when it came to Oscar.

Following the sinking of Cossack, Oscar was given the nickname “Unsinkable Sam” and was soon transferred to the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal, which by coincidence was instrumental in the destruction of Bismarck, along with Cossack. This assignment was not going to prove safer for Sam, and one might begin to wonder if he should be given another shore assignment…for the sake of the ships. When the Ark Royal was returning from Malta on November 14, 1941, it too was torpedoed, this time by U-81. Again they attempted to tow Ark Royal to Gibraltar, but they were unable to stop the inflow of water, so the attempt was futile. The carrier rolled over and sank 30 miles from Gibraltar. The good news was that due to the slow rate of the sinking, all but one crew member were able to be evacuated, along with, of course, Unsinkable Sam. The survivors, including Sam, who had been found clinging to a floating plank by a Motor Launch and described as “angry but quite unharmed,” were transferred to HMS Lightning and the same HMS Legion which had also rescued the crew of Cossack. Legion would itself be sunk in 1942, and Lightning in 1943. The life of a ship in wartime was not a safe one.

After the third ship sank under Sam’s paws, it was decided that maybe he shouldn’t be on a ship, so he was transferred first to the offices of the Governor of Gibraltar and then sent back to the United Kingdom, where he saw out the remainder of the war living in a seaman’s home in Belfast called the “Home for Sailors.” I think Sam had earned his place there. Sam died in 1955. A pastel portrait of Sam, which was titled “Oscar, the Bismarck’s Cat” by the artist Georgina Shaw-Baker is on display in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

Of course, as with all war stories, some authorities question whether Oskar/Sam’s biography might be a “sea story,” because for example, there are pictures of two different cats identified as Oskar/Sam. It is my opinion that whether it is true or not, it lends a lighthearted note to the otherwise tragic stories of war, and therefore, I choose to believe it is true.

My niece, Liz Masterson is a teacher of Journalism and English at Kelly Walsh High School in Casper, Wyoming. She is a dedicated teacher, who loves her job and her students, and they love her too. She isn’t an easy teacher, but the students learn from her, and they work hard for her, because she draws the best out of them.

My niece, Liz Masterson is a teacher of Journalism and English at Kelly Walsh High School in Casper, Wyoming. She is a dedicated teacher, who loves her job and her students, and they love her too. She isn’t an easy teacher, but the students learn from her, and they work hard for her, because she draws the best out of them.

This school year began normally, but as we all know, it has progressed in an anything but normal manner. Due to the COVID19 Pandemic, the schools have been closed since March 13th. Spring Break was supposed to have started on March 30th, but of course, it has been closed for two weeks already. In reality, the teachers and administration are working very hard, albeit at home, to prepare to finish this seriously unconventional school year. Since moving into the new part of Kelly Walsh, Liz’s students have been using Google Classroom for parts of their classes. That is most definitely a good thing, because it is Google Classroom that will be put into action to finish the school year. It will, however, be used differently than they are used to. Still, it is a form of remote learning, and it will allow the students and teachers to finish the school year. It has to be done, because you can’t just pass a generation of students with three months less class time than they should have.

For Liz, this unique situation is like being on hold or in limbo. Teachers are used to having their summer off, so two and a half months of no school feels normal, but summer is planned for…prepared for. This is nothing like that. She feels at loose ends. She misses her students and the classroom discussions they had. She misses the co-workers she had. She misses the sports, which she took pictures of for the annual, mostly because she is the biggest sports fan ever!! I think they were happy to have Liz take pictures of the sports, because she caught the essence of the plays. That’s because she saw the game from the mind of the players.

There are so many regrets that come with an unfinished school year, especially for the Seniors. This is their last year. so many things that they will never be able to do again…prom, graduation, the last part of being the top class. In sports, they miss the scouts, and possible chances at sports scholarships. For teachers, there are regrets too. Teachers are destined to teach, and to suddenly not be able to be stand before the class and see their faces as they get what is being taught, to see their smiling faces…it defeats the whole concept of

classroom teaching. This generation of students and their teachers can never get back the last three months of the 2020 school year, and that is a loss indeed. Nevertheless, today is Liz’s birthday, and I know that her students wish her the best, as do we, her family. And while this is a strange school year, I hope it will still be rewarding. Happy birthday Liz!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

classroom teaching. This generation of students and their teachers can never get back the last three months of the 2020 school year, and that is a loss indeed. Nevertheless, today is Liz’s birthday, and I know that her students wish her the best, as do we, her family. And while this is a strange school year, I hope it will still be rewarding. Happy birthday Liz!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Recently I read a novel that was based on a true story, called “The Alice Network,” by Kate Quinn. Knowing the book was a novel, I assumed that it was entirely fictional, but then I began to wonder, so I researched “The Alice Network” for myself. I found that “The Alice Network” was a very much true story, even if some of the characters in the story were fictional. The head of the Alice Network, Louise Marie Jeanne Henriette de Bettignies, was very much a real person.

Recently I read a novel that was based on a true story, called “The Alice Network,” by Kate Quinn. Knowing the book was a novel, I assumed that it was entirely fictional, but then I began to wonder, so I researched “The Alice Network” for myself. I found that “The Alice Network” was a very much true story, even if some of the characters in the story were fictional. The head of the Alice Network, Louise Marie Jeanne Henriette de Bettignies, was very much a real person.

Louise Marie Jeanne Henriette de Bettignies was born on July 15, 1880 to Henri de Bettignies and Julienne Mabille de Poncheville. She was fluent in French and English, with a good mastery in German and Italian. It made her a perfect candidate for the spy network. Louise became a French secret agent who spied on the Germans for the British during World War I using the pseudonym of Alice Dubois, hence “The Alice Network.” She had under her direction, a number of men and women who mainly worked in the area of Lille, in German occupied France. Her people listened inconspicuously to the talk of the German soldiers when they were not aware, and therefore, not careful to guard their tongues. The gleaned intel was then passed to couriers, of which Louise was one, to be transported by car, train, or on foot to the military leaders they worked for. It was a dangerous occupation, but the spies in the network wanted to serve in the war effort, and this was their chance.

Spies in “The Alice Network” and other such networks, went to work in jobs that were basically normal everyday jobs. They became waitresses, singers, shop workers, all in areas frequented by the enemy. They swallowed their disgust, in order to become almost invisible to the Germans. They never told anyone that they spoke German, because the Germans felt comfortable talking in front of these people who, they thought, couldn’t understand a word they said. It gave the spy networks just the edge they needed. Some spies, like Louise, spent time in makeshift hospitals writing letters in German dictated by dying Germans to their families. Dying men aren’t always careful with the information they give. A wealth of information was passed from these networks to the intelligence officers, and it often proved to be invaluable.

Louise lived with her sister, Germaine at 166 rue d’Isly. From October 4 to 13, 1914, by turning the only cannon that the Lille troops had, the defenders succeeded in deceiving the enemy and holding them for several days under an intense battle that destroyed more than 2,200 buildings and houses, particularly in the area of the station. Louise de Bettignies, aged 28, making full use of the four languages she spoke, including German and English. Through the ruins of Lille, she ensured the supply of ammunition and food to the soldiers who were still firing on the attackers. Then, since she had been a citizen of Lille since 1903, Louise made the decision in October 1914, to engage in resistance and espionage. Due in part to her ability to speak French, English, German, and Italian, she ran a vast intelligence network from her home in the North of France on behalf of the British army and the MI6 intelligence service under the pseudonym Alice Dubois. This network provided important information to the British through occupied Belgium and the Netherlands. The network is estimated to have saved the lives of more than a thousand British soldiers during the 9 months of full operation from January to September 1915.

“The Alice Network” of a hundred people, mostly in forty kilometers of the front to the west and east of Lille, was so effective that she was nicknamed by her English superiors “the queen of spies.” She smuggled men to England, provided valuable information to the Intelligence Service, and prepared for her superiors in London a grid map of the region around Lille. When the German army installed a new battery of artillery, even camouflaged, this position was bombed by the Royal Flying Corps within eight days. Another opportunity allowed her to report the date and time of passage of the imperial train carrying the Kaiser on a secret visit to the front at Lille. During the approach to Lille, two British aircraft bombed the train and emerged, but missed their target. The German command did not understand the unique situation of these forty kilometers of “cursed” front (held by the British) out of nearly seven hundred miles of front. One of her last messages announced the preparation of a massive German attack on Verdun in early 1916. The information was relayed to the French commander who refused to believe it. Incredible!!! After all her success, this worthless French commander refused to believe her. Idiot!!

Louise was arrested by the Germans on October 20, 1915 near Tournai. On March 16, 1916, in Brussels, she was sentenced to forced labor for life. After being held for three years, she died on September 27, 1918 as a result of pleural abscesses poorly operated upon at Saint Mary’s Hospital in Cologne. Her body was repatriated on February 21, 1920. On March 16, 1920 a funeral was held in Lille in which she was posthumously awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor, the Croix de guerre 1914-1918 with palm, and the British Military Medal, and she was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. Her body is buried in the cemetery of Saint-Amand-les-Eaux.

Imagine being given the name Haskay-bay-nay-natyl, at birth. Nevertheless, the name, which means “the tall man destined to come to a mysterious end,” was given to a baby born in the 1860s on the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. Because his name was strange and difficult to pronounce, the citizens of Globe simply called him “Kid.” Haskay-bay-nay-natyl was most likely a White Mountain Apache.

Imagine being given the name Haskay-bay-nay-natyl, at birth. Nevertheless, the name, which means “the tall man destined to come to a mysterious end,” was given to a baby born in the 1860s on the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. Because his name was strange and difficult to pronounce, the citizens of Globe simply called him “Kid.” Haskay-bay-nay-natyl was most likely a White Mountain Apache.

Eventually, the nickname was changed to the Apache Kid, and he was said to have been the fiercest Apache, other than Geronimo. The Apache Kid learned English at an early age, and began working odd jobs in Globe. Soon, he was befriended by the famous scout, Al Sieber. At that time, early settlers of the Southwest faced numerous raiding bands of Apache and General George Crook had come up with the idea to use Apache to fight other Apache. They began enlisting Apache Indians from San Carlos and other reservations. The enlisted scouts could locate the trails that the hunted Apache traveled. In 1881, the Kid enlisted in the Indian Scouts. He was so good at the job that he was promoted to sergeant in July, 1882. The following year he accompanied General George Crook on the expedition of the Sierra Madre.

The Geronimo Campaign of 1885-1886 found the Kid in Mexico early in 1885 with Sieber. When the Chief of Scouts was recalled that fall, Kid rode with him back to San Carlos.

Apache Kid re-enlisted with Lieutenant Crawford’s call for one hundred scouts for Mexican duty, and again went  south in late 1885. In the Mexican town of Huasabas, on the Bavispe River, the Kid nearly lost his life in a drunken riot that he participated in. The judge in the case decided that rather than see the Apache Kid shot by a Mexican firing squad, he would fine him twenty dollars. The Army sent him back to San Carlos. In May, 1887 the Apache Kid was left in charge of the Indian Scouts and guardhouse at San Carlos when Captain Pierce and Al Sieber, an Anglo scout, were both gone on business. Though the brewing of Tiswin, a beverage made of fermented fruit or corn, was illegal on the reservation, but the white officers gone, so the Indian Scouts decided to have a party. As the liquor flowed freely, a man named Gon-Zizzie killed the Apache Kid’s father, Togo-de-Chuz. Kid’s friends, in turn, killed Gon-Zizzie. However, the killing of Gon-Zizzie was not enough for the Apache Kid, who then went to the home of Gon-Zizzie’s brother, Rip, and killed him too.

south in late 1885. In the Mexican town of Huasabas, on the Bavispe River, the Kid nearly lost his life in a drunken riot that he participated in. The judge in the case decided that rather than see the Apache Kid shot by a Mexican firing squad, he would fine him twenty dollars. The Army sent him back to San Carlos. In May, 1887 the Apache Kid was left in charge of the Indian Scouts and guardhouse at San Carlos when Captain Pierce and Al Sieber, an Anglo scout, were both gone on business. Though the brewing of Tiswin, a beverage made of fermented fruit or corn, was illegal on the reservation, but the white officers gone, so the Indian Scouts decided to have a party. As the liquor flowed freely, a man named Gon-Zizzie killed the Apache Kid’s father, Togo-de-Chuz. Kid’s friends, in turn, killed Gon-Zizzie. However, the killing of Gon-Zizzie was not enough for the Apache Kid, who then went to the home of Gon-Zizzie’s brother, Rip, and killed him too.

When the Apache Kid and the four other scouts returned to San Carlos on June 1, 1857, both Captain Pierce and Al Sieber were there ahead of him. Captain Pierce ordered the scouts to disarm themselves and the Kid was the first to comply. As Pierce ordered them to the guardhouse to be locked up, a shot was fired from the  crowd who had gathered to watch the display of events. In no time, the shots became widespread and Al Seiber was hit in the ankle, which ended up crippling him for life. During the melee that followed, the Apache Kid and several other Apache fled. Though it was never determined who fired that shot that struck Sieber, it was for sure not the Kid nor the other four scouts ordered to the guardhouse as they had all been disarmed.

crowd who had gathered to watch the display of events. In no time, the shots became widespread and Al Seiber was hit in the ankle, which ended up crippling him for life. During the melee that followed, the Apache Kid and several other Apache fled. Though it was never determined who fired that shot that struck Sieber, it was for sure not the Kid nor the other four scouts ordered to the guardhouse as they had all been disarmed.

Over the next few years, Apache Kid was accused of, imprisoned for, escaped from or was released from prison for many crimes. It is not certain if he was guilty of these things or not. Some said that he was innocent and actually helped those under attack, but many said he was the attacker. Eventually, the Apache Kid disappeared and was never officially seen again. Some said he died, while other said he went to Mexico to a secret mountain hideaway. The jury is still out as to whether he was a good guy, or a bad guy, and the world will most likely never know.

It was 1914, and World War I was in the 5th month of a 51 month offensive. The war effort was in a bit of a transition period, following the stalemate of the Race to the Sea and the indecisive result of the First Battle of Ypres. As leadership on both sides reconsidered their strategies, hostilities entered a bit of a lull. The men were hoping for a break in the action for Christmas that year, but they had to wait for their orders. When the orders came down, it was not to be a Christmas truce, but rather a Christmas strike. As the first men to go forth prepared to make the first advances, some men were killed, and some returned. It was the way of war. The leadership wanted to take advantage of the possibility that the enemy might not expect a Christmas attack. One of the younger men…17 years old to be exact, couldn’t help himself. He began to sing Silent Night.His superiors ordered it to be quiet. They feared that the enemy was waiting in the darkness.

It was 1914, and World War I was in the 5th month of a 51 month offensive. The war effort was in a bit of a transition period, following the stalemate of the Race to the Sea and the indecisive result of the First Battle of Ypres. As leadership on both sides reconsidered their strategies, hostilities entered a bit of a lull. The men were hoping for a break in the action for Christmas that year, but they had to wait for their orders. When the orders came down, it was not to be a Christmas truce, but rather a Christmas strike. As the first men to go forth prepared to make the first advances, some men were killed, and some returned. It was the way of war. The leadership wanted to take advantage of the possibility that the enemy might not expect a Christmas attack. One of the younger men…17 years old to be exact, couldn’t help himself. He began to sing Silent Night.His superiors ordered it to be quiet. They feared that the enemy was waiting in the darkness.

Then, a miracle occurred. In the week leading up to the 25th of December, French, German, and British soldiers crossed trenches to exchange seasonal greetings…and to talk. In some areas, men from both sides ventured into what was called no man’s land, because to go there was to risk death. Nevertheless, on that Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, things seemed different. The soldiers took a chance and stepped forward, hoping to convince their enemies that they only wanted to bury their dead, and hoping that it would be  agreeable to stop the fighting for one hour to bury the dead. As they buried their dead, with heavy hearts, someone suggested that they take Christmas Day off. This was totally against their orders, and they knew that at some point they were going to have to go back and follow their orders. They were going to have to become enemies again. Still, for now…for this day, they mingled and exchange food and souvenirs. There were joint burial ceremonies and prisoner swaps. Men played games of football with one another, giving one of the most memorable images of the truce. Peaceful behavior was not ubiquitous, however, and fighting continued in some sectors, while in others the sides settled on little more than arrangements to recover bodies. Several meetings ended in carol-singing. Someone commented, “How many times in a life do you actually meet your enemy face to face.” It was almost strange to them, because these “enemies” were not the monsters they expected them to be. These were simply men, just like they were. I’m sure the men were in shock. it’s hard to have your total view of your enemy change so drastically and then have to follow your orders, pickup your weapons, and shoot at the same men again. The Christmas truce (German: Weihnachtsfrieden; French: Trêve de Noël) was a series of widespread but unofficial ceasefires along the Western Front of World War I around Christmas 1914.

agreeable to stop the fighting for one hour to bury the dead. As they buried their dead, with heavy hearts, someone suggested that they take Christmas Day off. This was totally against their orders, and they knew that at some point they were going to have to go back and follow their orders. They were going to have to become enemies again. Still, for now…for this day, they mingled and exchange food and souvenirs. There were joint burial ceremonies and prisoner swaps. Men played games of football with one another, giving one of the most memorable images of the truce. Peaceful behavior was not ubiquitous, however, and fighting continued in some sectors, while in others the sides settled on little more than arrangements to recover bodies. Several meetings ended in carol-singing. Someone commented, “How many times in a life do you actually meet your enemy face to face.” It was almost strange to them, because these “enemies” were not the monsters they expected them to be. These were simply men, just like they were. I’m sure the men were in shock. it’s hard to have your total view of your enemy change so drastically and then have to follow your orders, pickup your weapons, and shoot at the same men again. The Christmas truce (German: Weihnachtsfrieden; French: Trêve de Noël) was a series of widespread but unofficial ceasefires along the Western Front of World War I around Christmas 1914.

The Christmas Truces of 1914, while wonderful for the men, were not to be a Christmas tradition in World War I. The following year, a few units arranged ceasefires but the truces were not nearly as widespread as in 1914.  This was, in part, due to strongly worded orders from the high commands of both sides prohibiting truces. It was evident that while the mini-mutiny of 1914 was tolerated and the men were not punished, that this would not be tolerated in the future. It really didn’t matter, because the Soldiers were no longer amenable to truce by 1916. The war had become increasingly bitter after devastating human losses suffered during the battles of the Somme and Verdun, and the use of poison gas. While a Christmas truce would be nice in theory, bitter and angry feelings on both sides of a war make it an impractical idea. Still, in 1914, the miracle of the Christmas Truce was a wonderful treat for the men on all sides of a bitter war.

This was, in part, due to strongly worded orders from the high commands of both sides prohibiting truces. It was evident that while the mini-mutiny of 1914 was tolerated and the men were not punished, that this would not be tolerated in the future. It really didn’t matter, because the Soldiers were no longer amenable to truce by 1916. The war had become increasingly bitter after devastating human losses suffered during the battles of the Somme and Verdun, and the use of poison gas. While a Christmas truce would be nice in theory, bitter and angry feelings on both sides of a war make it an impractical idea. Still, in 1914, the miracle of the Christmas Truce was a wonderful treat for the men on all sides of a bitter war.

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

In my opinion, this dual language society would have caused numerous problems. The indication I get is that neither side could speak the language of the other, but I don’t know how a monarchy could rule, if the “commoners” could not understand the language and therefore the orders of the monarchy. French was spoken and learned by anyone in the upper  classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

To further confuse your preconceptions about the English language, the “British accent” was, in reality, created after the Revolutionary War, meaning contemporary Americans sound more like the colonists and British soldiers of the 18th century than contemporary Brits. Many people have made a point of how much they love the British accent, but I think very few people know the real story behind the British accent. In the 18th century and before, the British “accent” was the way we speak herein America. Of course, accents vary greatly  by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

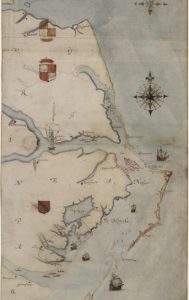

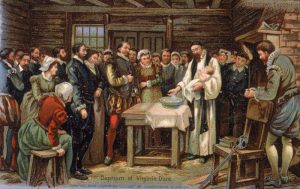

When I think of a lost people, I think of a tribe in Africa or somewhere very isolated, but I never think of someplace in America! Nevertheless, it happened right here in America. Of course, it was a long…long time ago. It was long before people could easily track someone down. The year was 1587, the day was July 22. That was the day when the new colony arrived in Roanoke, North Carolina, which was colonial Virginia. On August 18, 1587, the first English baby to be born in the Americas, Virginia Dare was born. The group had been dispatched by Sir Walter Raleigh, and was led by John White, who by the way, was Virginia Dare’s grandfather. Upon their arrival, they found nothing of the English garrison that had gone ahead, except one skeleton. The people really didn’t want to stay there after that, but the fleet commander, Simon Fernandez would not let them return to the ship, and the ships sailed with the promise of new supplies to come.

When I think of a lost people, I think of a tribe in Africa or somewhere very isolated, but I never think of someplace in America! Nevertheless, it happened right here in America. Of course, it was a long…long time ago. It was long before people could easily track someone down. The year was 1587, the day was July 22. That was the day when the new colony arrived in Roanoke, North Carolina, which was colonial Virginia. On August 18, 1587, the first English baby to be born in the Americas, Virginia Dare was born. The group had been dispatched by Sir Walter Raleigh, and was led by John White, who by the way, was Virginia Dare’s grandfather. Upon their arrival, they found nothing of the English garrison that had gone ahead, except one skeleton. The people really didn’t want to stay there after that, but the fleet commander, Simon Fernandez would not let them return to the ship, and the ships sailed with the promise of new supplies to come.

John White was not allowed to stay, and so returned to England on August 27, 1587…vowing to return in three months time. That was about the time of the Spanish Armada attack in 1588, which delayed White’s return to Roanoke. White tried desperately to return to the little colony for the next three years. When he was finally able to get there, he came rushing onshore, only to find that the colony was gone.

Among those missing was the little girl, Virginia Dare, White’s granddaughter. They had arrived on what would have been her third birthday…August 15. Whites return was delayed because of the Anglo-Spanish war, and the Spanish ships that robbed the expedition of the supplies they were taking over to the colonists. It is suspected that the colony disappeared during that war, but there is no clear clarification as to where they went or who took them.

Among those missing was the little girl, Virginia Dare, White’s granddaughter. They had arrived on what would have been her third birthday…August 15. Whites return was delayed because of the Anglo-Spanish war, and the Spanish ships that robbed the expedition of the supplies they were taking over to the colonists. It is suspected that the colony disappeared during that war, but there is no clear clarification as to where they went or who took them.

There has been much speculation as to the fate of the Roanoke Lost Colony, but the sure fate of the settlers left behind is unknown and the colony is known as the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke to this day. Over the years numerous attempts have been made to find the Lost Colony, including the Lost Colony DNA Project started in 2005. Recent investigations speculate that the Lost Colony relocated to where the Chowan River meets the Albemarle Sound in present day Bertie County, North Carolina. Nevertheless, recent discoveries found  European objects in the Hatteras Island area, including a sword hilt, broken English bowls, and a fragment of a slate writing tablet still inscribed with a letter. These could point to the presence of the colonists on Hatteras Island, some 50 miles southeast of their settlement on Roanoke Island. There were also some found at a site on the mainland 50 miles to the northwest. Some people have thought that the Native Americans took the people or at least assimilated them into their tribe, because there are in some of that modern day tribe of people with strangely gray eyes. I suppose we will never really know the reality of what happened, but I would rather think that the Native Americans took them in, than to think that they were killed.

European objects in the Hatteras Island area, including a sword hilt, broken English bowls, and a fragment of a slate writing tablet still inscribed with a letter. These could point to the presence of the colonists on Hatteras Island, some 50 miles southeast of their settlement on Roanoke Island. There were also some found at a site on the mainland 50 miles to the northwest. Some people have thought that the Native Americans took the people or at least assimilated them into their tribe, because there are in some of that modern day tribe of people with strangely gray eyes. I suppose we will never really know the reality of what happened, but I would rather think that the Native Americans took them in, than to think that they were killed.

In a war, secrecy is vital. The different sides must take whatever steps necessary to inform their troops and allies of their next step, without revealing the plan to the enemy. In World War II, America and her allies were having trouble with the level of secrecy they were able to achieve. It seemed that no matter what code they used, it was broken almost immediately. It did not help matters that many of the Japanese cryptographers had been educated in the United States. They spoke very good English, and they were very amazingly adept at breaking top secret military codes. For America and her allies, coming up with newer and more complicated codes was becoming more and more difficult, and the Japanese cryptographers seemed to break the new codes almost as quickly as they were developed. They were in real trouble. Then someone remembered a type of code that had been used in World War I, and things began to look up a little for America and the allies. The code was the use of Code Talkers from the Choctaw tribe.

In a war, secrecy is vital. The different sides must take whatever steps necessary to inform their troops and allies of their next step, without revealing the plan to the enemy. In World War II, America and her allies were having trouble with the level of secrecy they were able to achieve. It seemed that no matter what code they used, it was broken almost immediately. It did not help matters that many of the Japanese cryptographers had been educated in the United States. They spoke very good English, and they were very amazingly adept at breaking top secret military codes. For America and her allies, coming up with newer and more complicated codes was becoming more and more difficult, and the Japanese cryptographers seemed to break the new codes almost as quickly as they were developed. They were in real trouble. Then someone remembered a type of code that had been used in World War I, and things began to look up a little for America and the allies. The code was the use of Code Talkers from the Choctaw tribe.

That someone was war analyst Philip Johnston. Phillip, an American who fought in World War I, stationed in France, was too old to fight in World War II, but he wanted to aid in the effort anyway. As a boy, he spent time  on the Navajo Indian Reservation, where his parents were Protestant missionaries. He learned to speak the Navajo language with his playmates. Suddenly, the idea of a secret military code based on the Navajo language made perfect sense to him.

on the Navajo Indian Reservation, where his parents were Protestant missionaries. He learned to speak the Navajo language with his playmates. Suddenly, the idea of a secret military code based on the Navajo language made perfect sense to him.

In mid-April of 1942, Marine recruiting personnel went to the Navajo Reservation, and presented their plan. They enlisted thirty volunteers from the agency schools at Fort Wingate and Shiprock, New Mexico and Fort Defiance, Arizona. It would be a tall order for these volunteers. Each one had to be fluent in Navajo and English, but they also had to be physically fit, because they would be messengers in a combat zone. They were told that they would be specialists in the United States as well as over seas. Some of them were underage, but birth records on the Reservation were not well kept, so it was easy for volunteers to lie about or just not know their true age, and so they could participate. Carl Gorman, a 36-year-old Navajo from Fort Defiance, was too old to be considered by the Marines, so he lied about his age in order to be accepted.

Because the Navajo language was complicated, and due to the many different dialects, the Japanese could  never crack the code. They even captured a Navajo soldier and made him listen to the talk for hours, but because he had not been trained, he was still unable to crack the code. By 1945, there were about 540 Navajos who served in the Marines, and of those 375 to 420 were trained as code talkers. The rest served in other capacities. The code talkers payed an instrumental part in the success of the war effort. On June 4, 2014, Chester Nez, the last living original code talker, passed away. Once, in an interview he said, “My first transmission—one that did not involve coordinates—was one I will always remember: Beh-na-ali-tsosie a-knah-as-donih ah-toh nish-na-jih-goh dah-di-kad ah-deel-tahi, which translates to: Enemy machine gun nest on your right flank. Destroy.” These were great men, and our nation owes them a debt it can never repay.

never crack the code. They even captured a Navajo soldier and made him listen to the talk for hours, but because he had not been trained, he was still unable to crack the code. By 1945, there were about 540 Navajos who served in the Marines, and of those 375 to 420 were trained as code talkers. The rest served in other capacities. The code talkers payed an instrumental part in the success of the war effort. On June 4, 2014, Chester Nez, the last living original code talker, passed away. Once, in an interview he said, “My first transmission—one that did not involve coordinates—was one I will always remember: Beh-na-ali-tsosie a-knah-as-donih ah-toh nish-na-jih-goh dah-di-kad ah-deel-tahi, which translates to: Enemy machine gun nest on your right flank. Destroy.” These were great men, and our nation owes them a debt it can never repay.