denmark

Hans Island is a desolate little rock of an island locate near Greenland in the center of what is known as the Kennedy Channel of Nares Strait. This is the strait that separates Ellesmere Island from northern Greenland and connects Baffin Bay with the Lincoln Sea. The island is barren and uninhabited, measuring 0.5 square mile, 4,230 feet long and 3,934 feet wide. Hans Island is the smallest of three islands in Kennedy Channel off the Washington Land coast; the others are Franklin Island and Crozier Island. The strait at this point is 22 miles wide, placing the island within the territorial waters of both Canada and Greenland (Denmark). Technically, a line in the middle of the strait goes through the island.

Hans Island is a desolate little rock of an island locate near Greenland in the center of what is known as the Kennedy Channel of Nares Strait. This is the strait that separates Ellesmere Island from northern Greenland and connects Baffin Bay with the Lincoln Sea. The island is barren and uninhabited, measuring 0.5 square mile, 4,230 feet long and 3,934 feet wide. Hans Island is the smallest of three islands in Kennedy Channel off the Washington Land coast; the others are Franklin Island and Crozier Island. The strait at this point is 22 miles wide, placing the island within the territorial waters of both Canada and Greenland (Denmark). Technically, a line in the middle of the strait goes through the island.

Most people would look at this island and say, “Ok, it is technically half Canadian and half Greenland (Denmark), but seriously, who cares?” It is a piece of rock that has no value, so there it is and nobody cares. The problem is that…oddly, both sides care…a great deal. You might be wondering why, at this point. Well, you would not be alone. I am wondering why too. For some reason, Canada and Denmark have been…well, playfully fighting over the control of this little piece of ground. Every so often, when officials from each country visit, they leave a bottle of their country’s liquor as a…power move. It really makes no sense. The island has no reserves of oil or natural gas, or anything else that would make it valuable, and yet it is the subject of an ongoing territorial dispute between Denmark and Canada over who owns this little rock…and it’s such an odd dispute at that. It will barely increase the respective countries’ land mass and yet they continue to “fight” over it.

Unlike many other territory conflicts, this one is fought in a markedly peaceful way. The potential serious diplomatic implications aside, the Canadians and Danes take turns placing their flags on the island. This curious practice that has been going on since the 1980s. But it gets even odder. The island was first disputed in 1933, but largely forgotten during World War II. The unusual dispute began again in earnest in 1984 when, during a visit to the island, the Danish Minister for Greenland planted the national flag and left a message saying “Welcome to the Danish island” (“Velkommen til den danske ø” in Danish) along with (it is said) a bottle of brandy. Ever since then, when the flag on the island is periodically changed between the Danish and Canadian flag, the bottle is also replaced. The Canadians leave a bottle of Canadian Club and the Danes a bottle of schnapps.

While the conflict is “lighthearted,” it is really a serious conflict, and remains unresolved today. At one point, it looked like they might have a solution. On May 4, 2008, an international group of scientists from Australia, Canada, Denmark, and the UK installed an automated weather station on Hans Island. To me that makes the most sense. Just share the island or let it be considered international. That isn’t exactly what happened, however. There were a number of people who think that there might be some minerals on Hans Island, making  it a possible valuable island after all…and renewing the conflict. Oh boy, here we go again.

it a possible valuable island after all…and renewing the conflict. Oh boy, here we go again.

The conflict is as of today still unresolved, but there are suggestions on how to move forward. Arctic experts from Canada and Denmark propose making Hans Island into a condominium, a solution that has proven to resolve other conflicts in the past. I wasn’t sure what that was, but basically it is an agreement to share the island. It sometimes works temporarily, but usually doesn’t work long term. Most nations, Canada and Denmark included don’t like the idea of giving up their sovereignty. Time will tell, I guess, but if you ask me, the whole thing is…well, it’s just comical.

Not everyone was surprised at the coming murders of the Jews during the Holocaust. People hoped that the rumors were wrong, and that maybe they war would end before things got that bad, but most knew that if something wasn’t done, things were going to get ugly at some point. In the end, the non-Jews were forced to make a decision…take a stand, or stand by and watch millions of people die.

Not everyone was surprised at the coming murders of the Jews during the Holocaust. People hoped that the rumors were wrong, and that maybe they war would end before things got that bad, but most knew that if something wasn’t done, things were going to get ugly at some point. In the end, the non-Jews were forced to make a decision…take a stand, or stand by and watch millions of people die.

A Danish ambulance driver in Copenhagen, Denmark huddled over a local phone book, circling Jewish names. He had heard that all of Denmark’s Jews were going to be deported, and he knew this was his “moment of truth.” He knew he had to warn every one of these people, before it was too late. He wasn’t alone. Hundreds of everyday Danes sprang into action in late September 1943. They all had one collective goal in mind…to help their Jewish friends and neighbors escape the horrors they knew were coming.

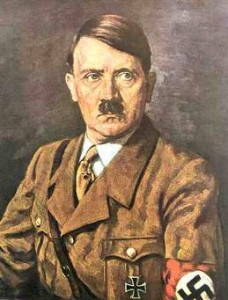

The plan was amazing. Hundreds of people helped Jewish people sneak out of Copenhagen and other towns. They quickly headed toward Danish shores and into the crowded holds of tiny fishing boats. Denmark was about to pull off a spectacular feat…the rescue of the vast majority of its Jewish population. Within a few hours of learning that the Nazis intended to wipe out Denmark’s Jews, nearly all of the Danish Jews had gone into hiding. Within a few days, most of them had escaped Denmark to neutral Sweden. In the end, over 90% of the Danish Jews were snatched out of the hands of Adolf Hitler and his goons, and it was all thanks to ordinary Danes, most of whom refused to accept credit for their ations. I call it a miracle, and the participants…angels!!

The German forces invaded Denmark in April 1940. The Danish government, rather than suffer an inevitable defeat by fighting back, didn’t resist the Nazi hoard. Instead, the Danish government negotiated with the Germans to insulate Denmark from the occupation. In the negotiations, the Nazis promised to be lenient with the country, respecting its rule and neutrality…like they would ever keep that promise. By 1943, tensions had reached a breaking point. Workers began to sabotage the war effort and the Danish resistance ramped up their efforts to fight the Nazis. In response, the Nazis told the Danish government to institute a harsh curfew, forbid public assemblies, and punish saboteurs with death. The Danish government refused, so the Nazis dissolved the government and established martial law.

The Nazis had always been a forbidding presence in Denmark, but now they began really making their presence known. Like everywhere else, the Danish Jews were to be their first targets. The Holocaust was spreading across occupied Europe, and without the protection of the Danish government, which had done its best to shield Jews from the Nazis after realizing that the Nazi promises were worthless, Denmark’s Jewish population was in danger. In late September 1943, the Nazis got word from Berlin that it was time to rid Denmark of its Jews. As was typical for the Nazis, they planned the raid to coincide with a significant Jewish holiday…in this case, Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Marcus Melchior, a rabbi, got word of the coming raid, and in Copenhagen’s main synagogue, he interrupted services. Melchior said, “We have no time now to continue prayers. We have news that this coming Friday night, the night between the first and second of October, the Gestapo will come and arrest all Danish Jews.” Melchior told the congregation that the Nazis had the names and addresses of every Jew in Denmark, and urged them to flee or hide.

Denmark’s panicked Jewish population sprang into action, but against all odds, so did its Gentiles. Hundreds of people spontaneously began to tell Jews about the upcoming action and help them go into hiding. It was, in the words of historian Leni Yahil, “a living wall raised by the Danish people in the course of one night.” It was amazing, and it can only be classified as a miracle. The Gentile people of Denmark were taking their lives into their own hands too, but they did not care, nor did they consider the cost. All they saw was the horrific injustice of the Nazi plan, and they could not abide by it.

No pre-existing plan had been put in place by the Danish people, but the Jewish people needed their help and nearby Sweden offered an obvious haven to those who were about to be deported. Sweden was still neutral and unoccupied by the Nazis, and they were a fierce ally. It was also close. Some areas of Denmark were just over three miles away from the Swedish coast. Once across, the Jews could apply for asylum there. The Danish culture has long been seafaring, in fact since Viking times. That said, there were plenty of fishing boats and other vessels to spirit Jews toward Sweden. But Danish fishermen were worried about losing their livelihoods and being punished by the Nazis if they were caught. So, rather than put their countrymen in peril, the resistance groups that swiftly formed to help the Jews managed to negotiate standard fees for Jewish passengers, then recruit volunteers to raise the money for passage. That way the fishermen got paid for their risk. The average price of passage to Sweden cost up to a third of a worker’s annual salary.

As often happens, there were fishermen who took advantage of the situation, but more who refused pay, acting without regard to personal gain. Boats were used for some 7,000 Danish Jews who fled to safety in neighboring Sweden. Passage was a terrifying ordeal. Jews gathered in fishing towns, hid on small boats, usually 10 to 15 at a time, giving their children sleeping pills and sedatives to keep them from crying, and struggled to maintain control during the hour-long crossing. Some boats, like the Gerda III, were boarded by Gestapo patrols. Gas came from strange sources. Careful rationing by groups like the “Elsinore Sewing Club,” a resistance unit, helped a few hundred Jews make the crossing.

There were failures sadly. In Gilleleje, a small fishing town, hundreds of refugees were being cared for by locals, when the Gestapo arrived. A collaborator had betrayed a group of Jews hiding in the town church’s attic. Eighty Jews were arrested. Others never got word of the upcoming deportations or were too old or incapacitated to seek help. In the end, about 500 Danish Jews were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto. Of the 500 who were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto, only 51 did not survive the Holocaust. Still, it was the most successful action of its kind during the Holocaust. Some 7,200 Danish Jews were ferried to Sweden.

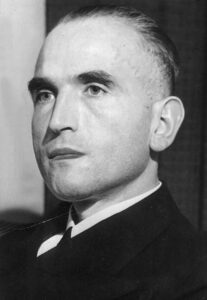

The rescue was not without German help either. God can reach people even in such a corrupt government. Werner Best, the German who had been placed in charge of Denmark, apparently tipped off some Jews to the

upcoming action and subtly undermined the Nazis’ attempts to stop the Danes from helping Danish Jews. Another helpful factor was that Denmark was one of the only places in Europe that had successfully integrated its Jewish population. Although there was anti-Semitism in Denmark before and after the Holocaust, the Nazis’ war on Jews was largely viewed as a war against Denmark itself.

upcoming action and subtly undermined the Nazis’ attempts to stop the Danes from helping Danish Jews. Another helpful factor was that Denmark was one of the only places in Europe that had successfully integrated its Jewish population. Although there was anti-Semitism in Denmark before and after the Holocaust, the Nazis’ war on Jews was largely viewed as a war against Denmark itself.