confederate soldiers

When things were heating up between the Confederate and Union soldiers around the town of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, most of the town’s 2,400 civilian residents did their best to make themselves scarce. They didn’t want to find themselves pulled into the conflict on the basis of simply being in the vicinity when the Union needed reinforcements, so they did what they could to get out of the way…either staying shut up in their houses and basements or leaving for someplace calmer.

When things were heating up between the Confederate and Union soldiers around the town of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, most of the town’s 2,400 civilian residents did their best to make themselves scarce. They didn’t want to find themselves pulled into the conflict on the basis of simply being in the vicinity when the Union needed reinforcements, so they did what they could to get out of the way…either staying shut up in their houses and basements or leaving for someplace calmer.

Not everyone felt that way, however. John Burns, who was about 69 years old at the time, although some said he was older, had fought a half-century earlier in the War of 1812. So, he was no stranger to war, but he took offence with the way a bunch of Rebels had come in and taken over his hometown. When he heard the sounds of battle on July 1, he told his wife he wanted to see what was going on. Grabbing his old flintlock musket, Burns left the house. He came across several Union officers and offered his services. The Union soldiers were basically amused by this strange character with his old musket, just showing up to offer to fight with them…and he wasn’t a young man, so that made it all the more strange. Still, Burns would not go away, and when he found a wounded soldier who would no longer need his rifle, Burns picked it up, and as the fighting heated up, Burns calmly took position behind a tree and began firing at the advancing Confederates. I guess the Union soldiers figured out pretty quickly that he meant business…especially when he was wounded three times in the intense fighting that day, and he still wouldn’t quit. One soldier recalled, “It must have been about noon when I saw a little old man coming up in the rear… I remember he wore a swallow-tailed coat with smooth brass buttons. He had a rifle on his shoulder. We boys began to poke fun at him as soon as he came amongst us, as we thought no civilian in his senses would [put] himself in such a place…”

The soldier then went on to say, “[When asked what] possessed him to come out there at such a time, he replied that ‘the rebels had either driven away or milked his cows, and that he was going to be even with them.’ About this time the enemy began to advance. Bullets were flying thicker and faster, and we hugged the ground about as close as we could. Burns got behind a tree and surprised us all by not taking a double-quick to the rear. He was as calm and collected as any veteran on the ground…I never saw John Burns after our movement to the right, when we left him behind his tree, and only know that he was true blue and grit to the backbone and fought until he was three times wounded.”

I’m sure it really upset the soldiers when they were forced to leave the injured Burns behind as they were ordered to retreat through the town. Burns was then found by the Confederates. Of course, since he had no uniform, they didn’t know that he wasn’t just a civilian who had been caught in the crossfire. Had they known he was fighting against them, they might have executed him, but a wise Burns had gotten rid of his weapon and pretended to be that helpless, unfortunate civilian who had been passing by at the wrong time. So, the Confederate surgeons treated him, and he was allowed to return home. The Confederates were none the wiser, and Burn had exacted his revenge. Burns was a happy man, because it just doesn’t get any better than that!!

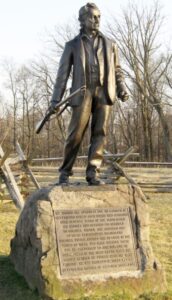

So impressed were the Union soldiers with John Burns, that his story was told to their superiors, and Burns is now memorialized with a statue on the Gettysburg battlefield, and his valor was called out in an after-action report by Major General Abner Doubleday. The memorial reads: “My thanks are specially due to a citizen of Gettysburg named John Burns who although over 70 years of age shouldered his musket and offered his services to Colonel Wister, One Hundred and Fiftieth Pennsylvania Volunteers. Colonel Wister advised him to fight in the woods as there was more shelter there but he preferred to join our line of skirmishers in the open fields. When the troops retired he fought with the Iron Brigade. He was wounded in three places.” John Burns truly was a civilian hero, but the real moral of the story is “Don’t mess with the cows.”

So impressed were the Union soldiers with John Burns, that his story was told to their superiors, and Burns is now memorialized with a statue on the Gettysburg battlefield, and his valor was called out in an after-action report by Major General Abner Doubleday. The memorial reads: “My thanks are specially due to a citizen of Gettysburg named John Burns who although over 70 years of age shouldered his musket and offered his services to Colonel Wister, One Hundred and Fiftieth Pennsylvania Volunteers. Colonel Wister advised him to fight in the woods as there was more shelter there but he preferred to join our line of skirmishers in the open fields. When the troops retired he fought with the Iron Brigade. He was wounded in three places.” John Burns truly was a civilian hero, but the real moral of the story is “Don’t mess with the cows.”

Anyone who has studied history in school knows about the Civil War. It was, of course, fought over slavery. The South wanted to keep the slaves and the North wanted to free the slaves. The Civil War was unique in another way too. Most wars are fought with soldiers who are rough and tough, ready to take on the elements, and battle to the death for their cause. The Civil War was that too, but the men of the South during the Civil War Era, were part of an era of the southern belles and southern gentlemen. This was an era when a type of lifestyle was borrowed from the English countryside, and basically transplanted into the American south. The lifestyle included a glorification of elegant horse riding, hunting, and of course, etiquette. This era and the people in it felt like there was a proper way to do things and that a certain level of decorum must be kept at all costs, in order to preserve their way of life.

Anyone who has studied history in school knows about the Civil War. It was, of course, fought over slavery. The South wanted to keep the slaves and the North wanted to free the slaves. The Civil War was unique in another way too. Most wars are fought with soldiers who are rough and tough, ready to take on the elements, and battle to the death for their cause. The Civil War was that too, but the men of the South during the Civil War Era, were part of an era of the southern belles and southern gentlemen. This was an era when a type of lifestyle was borrowed from the English countryside, and basically transplanted into the American south. The lifestyle included a glorification of elegant horse riding, hunting, and of course, etiquette. This era and the people in it felt like there was a proper way to do things and that a certain level of decorum must be kept at all costs, in order to preserve their way of life.

Tobacco played the central role in defining social class, local politics, and the labor system. In fact, it shaped the entire life of the region, and in doing so, actually shaped the Civil War. While the Civil War was a war, somehow the men of the South who fought in it felt like it needed to have that high level of decorum and decency. Tradition needed to be kept and carried on and while they knew that they were fighting a war, I’m not entirely sure that they understand that there would be, by necessity, loss of life and loss of that decorum and etiquette. For the men of the South especially, the Civil War was one of the most devastating events to challenge their way of life. This was also the most devastating event ever to occur on North American soil. While the loss of life was great, and in fact the Civil War caused more Americans to lose their lives than both World War I and World War II combined, the people of the South lost much of that “British Countryside” lifestyle that they thought so essential…and afterward, they didn’t quite know how to recover from that. The Confederate Army wanted to separate from the Union and maintain slavery, and the fight to combat that notion didn’t end until 1865. The differing ideas were a cause for rift long after the war was over.

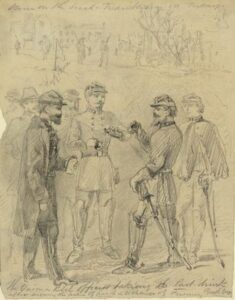

Nevertheless, despite the high stakes, the American soldiers from both sides still had several unofficial truces. Wars are usually long and tedious, and sometimes the men just needed to stop the fighting for a short time and try to be human again. Although these unofficial truces or ceasefires were usually frowned upon by military superiors, the men on either side would frequently call truces at the frontlines so Union and Confederate soldiers could chat, share information, and trade smokes. Imagine that…as the fighting is heavy, someone yells, “Wait…Smoke Break!!” Then both sides would stop shooting, walk out to the middle of te battlefield, and everyone would light a cigarette. I’m sure that’s not exactly how it happened, but they did actually hold such unofficial truces at times.

Nevertheless, despite the high stakes, the American soldiers from both sides still had several unofficial truces. Wars are usually long and tedious, and sometimes the men just needed to stop the fighting for a short time and try to be human again. Although these unofficial truces or ceasefires were usually frowned upon by military superiors, the men on either side would frequently call truces at the frontlines so Union and Confederate soldiers could chat, share information, and trade smokes. Imagine that…as the fighting is heavy, someone yells, “Wait…Smoke Break!!” Then both sides would stop shooting, walk out to the middle of te battlefield, and everyone would light a cigarette. I’m sure that’s not exactly how it happened, but they did actually hold such unofficial truces at times.

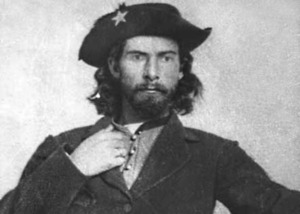

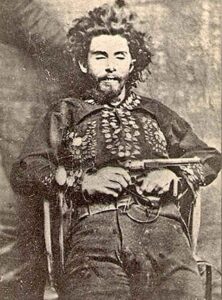

William T Anderson’s life was always rather a violent one, but it escalated when his sister died while in the custody of the Union soldiers during the Civil War. Anderson was born around 1840 in Hopkins County, Kentucky, to William and Martha Anderson. His siblings were Jim, Ellis, Mary, Josephine, and Martha. His schoolmates recalled him as a well-behaved, reserved child, so they might be surprised to see how he ended up. Anderson began to support himself early on, by stealing and selling horses in 1862. After a Union loyalist judge killed his father, Anderson killed the judge and fled to Missouri. He was always one to exact revenge for anything in which he felt that he or his family were wronged. In Missouri, he robbed travelers and killed several Union soldiers.

William T Anderson’s life was always rather a violent one, but it escalated when his sister died while in the custody of the Union soldiers during the Civil War. Anderson was born around 1840 in Hopkins County, Kentucky, to William and Martha Anderson. His siblings were Jim, Ellis, Mary, Josephine, and Martha. His schoolmates recalled him as a well-behaved, reserved child, so they might be surprised to see how he ended up. Anderson began to support himself early on, by stealing and selling horses in 1862. After a Union loyalist judge killed his father, Anderson killed the judge and fled to Missouri. He was always one to exact revenge for anything in which he felt that he or his family were wronged. In Missouri, he robbed travelers and killed several Union soldiers.

Anderson became a guerrilla, when his family was living in Council Grove, Territory of Kansas at the start of the Civil War. After William Quantrill’s raid on Aubry, Kansas on March 7, 1862, a Federal company from Olathe, Kansas sent a patrol from Company D, Eighth Kansas Jayhawker Regiment to investigate. Their mission was to seek out Southern sympathizers living nearby, who might be accused of aiding the raiders. Anderson’s father and uncle were named as such, and when the Jayhawker company arrived at the Anderson farm on March 11th, William and his younger brother Jim were delivering 15 head of cattle to the US commissary agent at Fort Leavenworth. When the brothers returned to their farm, they found their father and uncle hanged in retaliation, their home burned to the ground, and all their possessions stolen. It was an act of war in their minds, because the men had no chance to defend themselves. Two days later Bill and his brother Jim were both riding with Quantrill’s Raiders, a group of Confederate guerrillas operating along the Kansas–Missouri border. Anderson moved his sisters from Kansas, and for a year they lived at various places stopping finally with the Mundy family on the Missouri side of the line near Little Santa Fe. When asked why he joined Quantrill, Anderson replied by saying, “I have chosen guerrilla warfare to revenge myself for wrongs that I could not honorable revenge otherwise. I lived in Kansas when this war commenced. Because I would not fight the people of Missouri, my native State, the Yankees sought my life but failed to get me. [They] revenged themselves by murdering my father, [and] destroying all my property.”

Anderson became a skilled bushwhacker and quickly earned the trust of the group’s leaders, William Quantrill and George M Todd. It was his bushwhacking skills that ultimately marked him as a dangerous man…and eventually led the Union to imprison his sisters. Then, after a building collapse in the makeshift jail in Kansas City, Missouri, left one of his sisters dead, while in custody and the others permanently maimed, Anderson devoted himself to revenge. He took a leading role in the Lawrence Massacre and later took part in the Battle of Baxter Springs, both in 1863. He later satisfied his revenge by hijacking a train full of Union troops and slaughtering 24 of them, thus giving him the name “Bloody Bill” Anderson.

By 1863, all Bill had left was a brother and two sisters, who had miraculously survived the August 13 Union jail collapse in Kansas City. The collapse wasn’t an accident. Union guards from the 9th Kansas Jayhawker Regiment, serving as provost guards in town, intentionally collapsed a three-story brick building on a number of young Southern female prisoners. Fourteen-year-old Josephine Anderson was killed in the collapse. Bill’s ten-year-old sister Martha’s legs were horribly crushed crippling her for life, and his sixteen-year-old sister Mary suffered serious back injuries and facial lacerations. Both girls would carry their physical and emotional scars for the rest of their lives. War is an ugly thing, and unfortunately, sometimes unscrupulous people do things  they shouldn’t. The atrocity at the jail was a war crime and should have been punished as such, but I suppose that didn’t justify the murders that followed, because there was no proof that those murdered were involved in any way.

they shouldn’t. The atrocity at the jail was a war crime and should have been punished as such, but I suppose that didn’t justify the murders that followed, because there was no proof that those murdered were involved in any way.

Union military leaders ordered Lieutenant Colonel Samuel P Cox to kill Anderson and provided him with a group of experienced soldiers. A local woman saw Anderson soon after he left Glasgow and told Cox where he was. On October 26, 1864, Cox pursued Anderson’s group with 150 men and engaged them in a battle called the Skirmish at Albany, Missouri. Anderson and his men charged the Union forces, killing five or six of them, but turned back under heavy fire. Only Anderson and one other man, the son of a Confederate general, continued to charge after the others had retreated. Anderson was hit by a bullet behind an ear, which most likely killed him instantly. Four other guerrillas were killed in the attack as well. The victory made a hero of Cox and led to his promotion.

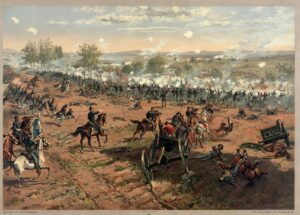

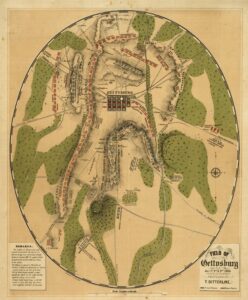

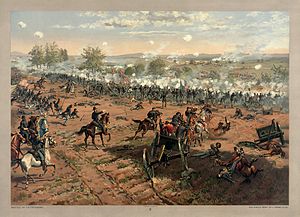

One hundred fifty one years ago today, a little battle that was a part of the Civil War, began. Many of the battles of the Civil War went without serious recognition, but not this one. It lasted only three days, but it was the turning point in the war. You have all heard of this little battle, of course…it was, the Battle of Gettysburg. It was fought between July 1 and July 3, 1863 in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The soldiers were all Americans…Confederate and Union. Some were related…fathers against sons, brother against brother. With this battle came the end of General Robert E Lee’s attempts to invade the north. The fighting was fierce with many casualties on both sides. The Union side came into the battle with 93,921 soldiers and lost 3,155 men, who were killed. Another 14,531 were wounded, and 5,369 were captured or missing. The Confederate side came into the battle with 71,699 soldiers and lost 4,708 men, who were killed. Another 12,693 were wounded, and 5,830 were captured or missing. This battle was devastating, no matter which side you were on. On November 19, 1863, President Lincoln dedicated the cemetery as the Gettysburg National Cemetery to honor the fallen Union soldiers, and to reiterate the purpose of the war. In that ceremony, President Lincoln gave his historic Gettysburg Address.

One hundred fifty one years ago today, a little battle that was a part of the Civil War, began. Many of the battles of the Civil War went without serious recognition, but not this one. It lasted only three days, but it was the turning point in the war. You have all heard of this little battle, of course…it was, the Battle of Gettysburg. It was fought between July 1 and July 3, 1863 in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The soldiers were all Americans…Confederate and Union. Some were related…fathers against sons, brother against brother. With this battle came the end of General Robert E Lee’s attempts to invade the north. The fighting was fierce with many casualties on both sides. The Union side came into the battle with 93,921 soldiers and lost 3,155 men, who were killed. Another 14,531 were wounded, and 5,369 were captured or missing. The Confederate side came into the battle with 71,699 soldiers and lost 4,708 men, who were killed. Another 12,693 were wounded, and 5,830 were captured or missing. This battle was devastating, no matter which side you were on. On November 19, 1863, President Lincoln dedicated the cemetery as the Gettysburg National Cemetery to honor the fallen Union soldiers, and to reiterate the purpose of the war. In that ceremony, President Lincoln gave his historic Gettysburg Address.

When my family went back to visit my sister in Keeseville, New York, we took a trip down the east coast, that included Gettysburg. I can’t tell you if any of my ancestors fought in that battle, but I can tell you that visiting Gettysburg National Cemetery, is something that stays with you. You can’t help but walk away a very changed person. That place has a hallowed feeling to it. When you know of the deaths that happened there, the blood that was shed, families that were destroyed, there is no other way to feel, but awe. They knew what they had to do, and they did what was needed. It didn’t matter how they felt about giving their lives, they all felt that their side was right, and they were willing to fight for what was right.

I will always remember the feelings I had standing there, looking at all those graves…thinking about all those lives lost. I thought about children without fathers and parents without their children. There was no way out of it. They had to fight. It was kill or be killed. And there was a very important purpose for their fighting. Even all those years ago, the feeling was still there. You felt the need to be very quiet, because to speak almost seemed wrong. I felt very honored to be in the presence of such courageous men. Our trip to Gettysburg was forty one years ago, but the way I felt while I was there has never left me. I can feel it now, as if I were standing there right now.