comanche

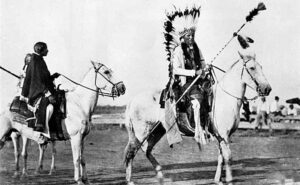

Oh The great Comanche chief and war leader, Quanah Parker became a leader at a young age, and he was known for his bravery and his aggression as a warrior. I was drawn to this chief mostly because of his unusual name…both first and last. The first name was one I had never heard before, and the last seemed unusual for an Indian. Parker was born around 1848, near Wichita Falls, Texas, and died February 23, 1911, at Cache, near Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Quanah was the son of Chief Peta Nocona and Cynthia Ann Parker, a white woman captured by the Comanches as a child. Quanah is a Native American name that means “fragrant, or sweet smelling.” Quanah later added his mother’s surname to his given name. Their family was very happy until 1860, when the Texas Rangers attacked their encampment on the Pease River. While the stories of this event vary, there is no doubt that changed Quanah’s family forever, when the Rangers decided that Cynthia Ann and her young daughter, Prairie Flower should be returned to her people, even though that was against her wishes. It is believed that Quanah and Nocona were not there when the raid took place.

The great Comanche chief and war leader, Quanah Parker became a leader at a young age, and he was known for his bravery and his aggression as a warrior. I was drawn to this chief mostly because of his unusual name…both first and last. The first name was one I had never heard before, and the last seemed unusual for an Indian. Parker was born around 1848, near Wichita Falls, Texas, and died February 23, 1911, at Cache, near Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Quanah was the son of Chief Peta Nocona and Cynthia Ann Parker, a white woman captured by the Comanches as a child. Quanah is a Native American name that means “fragrant, or sweet smelling.” Quanah later added his mother’s surname to his given name. Their family was very happy until 1860, when the Texas Rangers attacked their encampment on the Pease River. While the stories of this event vary, there is no doubt that changed Quanah’s family forever, when the Rangers decided that Cynthia Ann and her young daughter, Prairie Flower should be returned to her people, even though that was against her wishes. It is believed that Quanah and Nocona were not there when the raid took place.

Quanah Parker was the last chief of the Kwahadi (Quahadi) band. He mounted an unsuccessful war against white expansion in northwestern Texas between 1874 and 1875. When that failed, he became the main spokesman and peacetime leader of the Native Americans in the region, a role which he performed for 30 years.

Quanah was a tall and muscular man, who became a full warrior at age 15. His reputation as an aggressive and fearless fighter was established after a series of successful raids. He became a war chief at a relatively young age as well, having gained the respect of his people. Quanah moved between several Comanche bands before joining the fierce Kwahadi, who were particularly bitter enemies of the hunter. The white Buffalo hunters had appropriated the best land on the Texas frontier and were decimating the buffalo herds. In order to stem the onslaught of Comanche attacks on settlers and travelers, the US government relegated the Indians to reservations in 1867. Quanah and his band refused to cooperate and continued their raids. Attempts by the US military to locate them were unsuccessful. In June 1874 Quanah and Isa-Tai, a medicine man who claimed to have a potion that would protect the Indians from bullets, gathered 250–700 warriors from among the Comanche, Cheyenne, and Kiowa and attacked about 30 white buffalo hunters quartered at Adobe Walls, Texas. The raid was a failure for the Kwahadi because a saloon owner had allegedly been warned of the attack, and the US military retaliated in force in what became known as the Red River Indian War. Quanah’s group held out on the Staked Plains for almost a year before he finally surrendered at Fort Sill.

Eventually Quanah agreed to settle on a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma, and he persuaded other Comanche bands to conform too. He soon became known as the principal chief of all Comanche. It was a position that had never existed before, and so was a great honor. As the chief of all Comanche, over the next three decades, he was the main interpreter of white civilization to his people, encouraging education and agriculture. He also tried to be an advocate on behalf of the Comanche, and soon became a successful businessman as well. Quanah also maintained elements of his own Indian culture, including polygamy, and he played a major role in creating a Peyote Religion that spread from  the Comanche to other tribes. He soon became a national figure, developing friendships with numerous notable men, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who invited Quanah to his inauguration in 1905. Roosevelt also visited Quanah at the chief’s home, a 10-room residence known as Star House, in Cache, Oklahoma.

the Comanche to other tribes. He soon became a national figure, developing friendships with numerous notable men, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who invited Quanah to his inauguration in 1905. Roosevelt also visited Quanah at the chief’s home, a 10-room residence known as Star House, in Cache, Oklahoma.

Quanah passed away in 1911, and was buried next to his mother, whose assimilation back into white civilization had been very difficult. Her white family blocked her repeated attempts to rejoin the Comanche, and in 1864 Prairie Flower died. Cynthia Ann was miserable and reportedly starved herself to death in 1870.

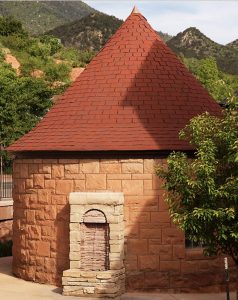

People of different, religions, races, and geological locations have been battling it out since time began. When the first white men came into the Western wilderness of America they found the tribes of Shoshone and Comanche Indians already at odds. It seems that their differences began at Manitou Springs. This “Saratoga of the West” is nestled in a hollow in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. It was in old days a common meeting ground for several families of Indians…possibly bringing about the fights over it. While there were fights over the area, councils were held in safety there, for no Indian dared provoke the wrath of the Manitou whose breath sparkled in the “medicine waters.”

People of different, religions, races, and geological locations have been battling it out since time began. When the first white men came into the Western wilderness of America they found the tribes of Shoshone and Comanche Indians already at odds. It seems that their differences began at Manitou Springs. This “Saratoga of the West” is nestled in a hollow in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. It was in old days a common meeting ground for several families of Indians…possibly bringing about the fights over it. While there were fights over the area, councils were held in safety there, for no Indian dared provoke the wrath of the Manitou whose breath sparkled in the “medicine waters.”

As the story goes, “centuries ago a Shoshone and a Comanche stopped at Manitou Springs on their return from a hunt to get a drink of water. The Shoshone had been successful, but the Comanche was empty-handed and ill-tempered, jealous of the other’s skill and fortune. Flinging down the fat deer that he was bearing homeward on his shoulders, the Shoshone bent over the spring of sweet water, and, after pouring a handful of it on the ground, as a libation (an act of pouring a liquid as a sacrifice) to the spirit of the place, he put his lips to the surface.”

The Comanche saw an opportunity to vent his anger. His quarrel began like this, “Why does a stranger drink

the water at the spring that his children may drink it undefiled. I am Ausaqua, chief of Shoshone, and I drink at the head-water. Shoshone and Comanche are brothers. Let them drink together. No. The Shoshone pays tribute to the Comanche, and Wacomish leads that nation to war. He is chief of the Shoshone as he is of his own people. Wacomish lies. His tongue is forked, like the snake’s. His heart is black. When the Great Spirit made his children he said not to one, ‘Drink here,’ and to another, ‘Drink there,’ but gave water that all might drink.”

the water at the spring that his children may drink it undefiled. I am Ausaqua, chief of Shoshone, and I drink at the head-water. Shoshone and Comanche are brothers. Let them drink together. No. The Shoshone pays tribute to the Comanche, and Wacomish leads that nation to war. He is chief of the Shoshone as he is of his own people. Wacomish lies. His tongue is forked, like the snake’s. His heart is black. When the Great Spirit made his children he said not to one, ‘Drink here,’ and to another, ‘Drink there,’ but gave water that all might drink.”

It is said, that the Shoshone didn’t answer, but as Ausaqua stooped toward the bubbling surface Wacomish crept behind him. He jumped on him and pushed his head under the water, holding it there until he drowned. It is said that as Wacomish “pulled the dead body from the spring the water became agitated, and from the bubbles arose a vapor that gradually assumed the form of a venerable Indian, with long white locks, in whom the murderer recognized Waukauga, father of the Shoshone and Comanche nation, and a man whose heroism and goodness made his name revered in both these tribes.” The face of the patriarch was dark with wrath, and he cried, in terrible tones, “Accursed of my race! This day thou hast severed the mightiest nation in the world. The blood of the brave Shoshone appeals for vengeance. May the water of thy tribe be rank and bitter in their throats.”

“Then, whirling up an elk-horn club, he brought it full on the head of the wretched man, who cringed before him. The murderer’s head was burst open and he tumbled lifelessly into the spring, that to this day is nauseous, while, to perpetuate the memory of Ausaqua, the Manitou smote a neighboring rock, and from it gushed a fountain of delicious water. The bodies were found, and the partisans of both the hunters began on that day a long and destructive warfare, in which other tribes became involved until mountaineers were arrayed against plainsmen through all that region.”

“Then, whirling up an elk-horn club, he brought it full on the head of the wretched man, who cringed before him. The murderer’s head was burst open and he tumbled lifelessly into the spring, that to this day is nauseous, while, to perpetuate the memory of Ausaqua, the Manitou smote a neighboring rock, and from it gushed a fountain of delicious water. The bodies were found, and the partisans of both the hunters began on that day a long and destructive warfare, in which other tribes became involved until mountaineers were arrayed against plainsmen through all that region.”

Of course, all this is folk lore, but the springs are real. They are Iron Spring, Twin Spring, Stratton Spring, Shoshone Spring, Wheeler Spring, Cheyenne, Soda and Navajo Springs, and Seven Minute Spring.

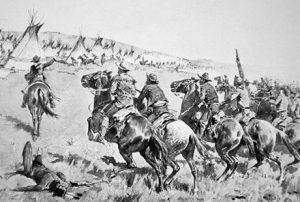

The battle for lands owned, desired, or presumed owned, is one that has raged in the United States for many, many years. When the pilgrims first came to the new world, it did not seem like a problem to the Native Americans, but as more and more “White Men” came, the Native Americans could see the writing on the wall. so to speak. They knew that their wide open spaces were in jeopardy, and they were determined not to lose the battle for their most prized possession…land. In the 18th and 19th centuries settlers from Europe moved westward across America in a steady wave. The migration overwhelmed ancient tribes like the Iroquois, the Cherokee, and the Shawnee. But when the settlers reached Texas and the lands of the Comanche, the migration stopped in it’s tracks. Many of the Indians back then were somewhat like the settlers. They had their villages, and they stayed in one place, or moved slowly from one place to another. The Comanche were just like that, until the horse arrived in North America. But the Comanche adapted to the horse like no other Native American group. They became nomads, following the buffalo, and as they exploded across the Texas plains, they virtually wiped out the Apache. Their enormous horse herds were legendary, as were their riding skills. While the Cheyenne and Sioux would dismount before battles, the Comanche mastered the art of fighting on horseback. They planted no crops, built no settlements, and shunned complex ritual or religion. The name “Comanche” was given to them by the Utes. It means “enemies.”

The battle for lands owned, desired, or presumed owned, is one that has raged in the United States for many, many years. When the pilgrims first came to the new world, it did not seem like a problem to the Native Americans, but as more and more “White Men” came, the Native Americans could see the writing on the wall. so to speak. They knew that their wide open spaces were in jeopardy, and they were determined not to lose the battle for their most prized possession…land. In the 18th and 19th centuries settlers from Europe moved westward across America in a steady wave. The migration overwhelmed ancient tribes like the Iroquois, the Cherokee, and the Shawnee. But when the settlers reached Texas and the lands of the Comanche, the migration stopped in it’s tracks. Many of the Indians back then were somewhat like the settlers. They had their villages, and they stayed in one place, or moved slowly from one place to another. The Comanche were just like that, until the horse arrived in North America. But the Comanche adapted to the horse like no other Native American group. They became nomads, following the buffalo, and as they exploded across the Texas plains, they virtually wiped out the Apache. Their enormous horse herds were legendary, as were their riding skills. While the Cheyenne and Sioux would dismount before battles, the Comanche mastered the art of fighting on horseback. They planted no crops, built no settlements, and shunned complex ritual or religion. The name “Comanche” was given to them by the Utes. It means “enemies.”

Unfortunately for the Comanche, they were no match for the settlers. After being beaten early on, the Comanche avoided direct conflict for the most part. They preferred to attack undefended farmhouses, slaughtering the inhabitants. It worked, the settlers were too afraid to travel into Comanche territory, and European expansion almost came to a screeching halt. In 1858, after a particularly bloody year, the Texas Rangers were ordered to take care of the Comanche. The empire of the Texas plains was a brutal and unchanging grassland of deadly heat and vast wildfires. No European had traveled very far into the territory, but now the Rangers intended to do just that. They were accompanied by a group of Tonkawas, a local tribe hated by other Native Americans for their cannibalism. The Comanche slaughtered the Tonkawas whenever possible, and the survivors were out for revenge. Together, the Rangers and the Tonkawas traveled for weeks, even fording stretches of pure quicksand, until they discovered a huge Comanche camp stretching along a creek in the Antelope Hills. The Comanche sprang onto their horses, but it was too late. They never expected to be attacked in the heart of the Comancheria and were in no position to fight. It looked as if all was lost, and indeed it was, but they did not know that yet.

Suddenly, Chief Iron Jacket rode out of the chaos. His true name was Pobishequasso, but he was known as Iron Jacket for his ancient coat of Spanish armor, a family heirloom looted from the corpse of some unlucky conquistador. He exhaled great breaths of air as he rode toward the Rangers, working his medicine, which was said to blow bullets off target. The Rangers and the Tonkawas opened fire, but Iron Jacket kept coming. The bullets seemed to bounce off him, and for a moment, it seemed that he was unstoppable. Then, the magic ended. A hail of rifle fire cut down his horse, and a second volley finished Pobishequasso. His followers…armed only with lances and ancient muskets..fled, pursued by the Rangers, who picked off at least 76 of them. In the years that followed, the settlers became bolder, launching numerous raids into the Comancheria. Iron Jacket’s rusting armor was broken up for souvenirs. The reign of the Comanche was over.