civil war

People love to fight…be it in a war, debate, argument, or feud. It’s not so much a matter of loving to fight really, as it is an inability to get along, due to very differing opinions and ideas. One of the best known of all the feuds in Texas was the Lee-Peacock Feud. This feud took place in northeast Texas following the Civil War. It was a continuation of the war that would last for four bloody years after the rest of the nation had laid down their arms.The feud was fought in the Corners region of northeast Texas, where Grayson, Fannin, Hunt, and Collin Counties converged in an area known as the “Wildcat Thicket.” This thicket, covering many square miles, was so dense with trees, tall grass, brier brush, and thorn vines, that few people had even ventured into it until the Civil War, when it became a haven for army deserters and outlaws. It was in the northern part of this thicket that Daniel W Lee had built his home and raised his son, Bob Lee, who would become one of the leaders in the feud that was to come.

People love to fight…be it in a war, debate, argument, or feud. It’s not so much a matter of loving to fight really, as it is an inability to get along, due to very differing opinions and ideas. One of the best known of all the feuds in Texas was the Lee-Peacock Feud. This feud took place in northeast Texas following the Civil War. It was a continuation of the war that would last for four bloody years after the rest of the nation had laid down their arms.The feud was fought in the Corners region of northeast Texas, where Grayson, Fannin, Hunt, and Collin Counties converged in an area known as the “Wildcat Thicket.” This thicket, covering many square miles, was so dense with trees, tall grass, brier brush, and thorn vines, that few people had even ventured into it until the Civil War, when it became a haven for army deserters and outlaws. It was in the northern part of this thicket that Daniel W Lee had built his home and raised his son, Bob Lee, who would become one of the leaders in the feud that was to come.

When the Civil War broke out, Bob Lee, by that time married with three children, quickly joined the Confederate Army, serving with the Ninth Texas Cavalry. Other young men in the area, including the Maddox brothers…John, William, and Francis; their cousin Jim Maddox, and several of the Boren boys, also joined the Ninth. Towards the end of the war, Bob heard that the Union League, an organization that worked for the protection of the blacks and Union sympathizers, had set up its North Texas headquarters at Pilot Grove, just about seven miles away from the Lee family homes.

The head of the Union League was a man named Lewis Peacock, who had arrived in Texas in 1856 and lived just south of Pilot Grove. Federal Troops were sent to Texas to aid in reconstruction efforts. By the time the Confederate soldiers returned to their homes in northeast Texas, the area was already in heavy conflict. Whether they owned slaves or not, most area residents resented the intrusion of Reconstruction ideals and new laws. When Bob Lee returned home, he was seen as a natural leader for the “Civil War” that was still being fought in northeast Texas.

To Peacock, Lee was seen as a threat to his cause and to reconstruction itself. To remove this threat, the Union League conceived of the idea to extort money from Lee. Peacock and his cohorts arrived at Lee’s house one night and “arrested” him, allegedly for crimes that he had committed during the Civil War. Lee would later say that he recognized the men as Lewis Peacock, James Maddox, Bill Smith, Sam Bier, Hardy Dial, Doc Wilson, and Israel Boren. Stating to Lee that he was to be taken into Sherman, they instead stopped in Choctaw Creek bottoms, where they took Lee’s watch, a $20 gold coin, and forced him to sign a promissory note for $2,000. The Lee’s refused to pay the note, bringing suit in Bonham, Texas and winning the case. This was the start of an all-out war, known as the Lee-Peacock Feud.

Both men gathered their friends and sympathizers and from 1867 through June 1869, a second “Civil War” raged in northeast Texas. An estimated 50 men losing their lives. By the summer of 1868, it had become so heated that the Union League requested help from the Federal Government, to which General JJ Reynolds posted a reward of $1,000 for the capture of Bob Lee. In late February, 1867, Lee was in a store in Pilot Grove when he ran across Jim Maddox, one of the men who had kidnapped him. Confronting Maddox, Lee offered Maddox a gun so they could fight. When Lee turned around to walk away, a bullet grazed his ear and head and he fell to the ground unconscious. Lee was taken to Dr William H Pierce, who treated him in his home. A report went to Austin to the Headquarters of the Fifth Military District under command of General John J. Reynolds, and the following entry was made in his ledger: “Murder and Assaults with Intent to Kill”, listed as criminals were James Maddox and John Vaught, listed as injured was Robert Lee. The charge: “Assault with intent to murder.” The result: “Set aside by the Military”. A few days later, on February 24, 1867, while Lee was still, convalescing in Pierce’s home, the doctor was shot to death by Hugh Hudson, a known Peacock man. Lee swore to avenge Pierce’s death and as word spread to both sides of the conflict, neighbors in the thickets of Four Corners began to arm themselves.

Hugh Hudson, the doctor’s killer was later shot at Saltillo, a teamster’s stop on the road to Jefferson. The feud had begun in full force. In 1868, Lige Clark, Billy Dixon, Dow Nance, Dan Sanders, Elijah Clark, and John Baldock were killed and many others wounded. Even Peacock suffered a wound at the hands of Lee’s followers. On August 27, 1868, General J. J. Reynolds issued the $1,000 reward for Bob Lee, dead or alive, an act that attracted bounty hunters from all over the country to the “Four Corners.” Three of these men, union sympathizers from Kansas, converged on the area in the early spring of 1869 to try to capture Lee. Instead, all three were found dead on the road. Bob Lee, in the meantime, had set up a hideout in the “Wildcat Thicket.”

General JJ Reynolds responded by dispatching the Fourth United States Cavalry to search for Lee and attempt to settle the trouble in the area. As they began a search from house to house for Lee, in which several gun battles ensued and several men were killed. In the end, one of Bob Lee’s “supporters,” a man named Henry Boren, betrayed him to the cavalry who shot down Lee on May 24, 1869. Later, Boren was shot down by his  own nephew, Bill Boren, who was a Lee supporter and felt that a “traitor” had to be put to death. After he killed his uncle, Bill Boren left the area and began to ride with John Wesley Hardin.

own nephew, Bill Boren, who was a Lee supporter and felt that a “traitor” had to be put to death. After he killed his uncle, Bill Boren left the area and began to ride with John Wesley Hardin.

As the Texas authorities had hoped, the killing of Lee began to dissolve the heated dispute, as many men scattered to other parts of the state. Though they were fewer in number, the “war” continued for two years, as more men were killed in both the four-corners region and other parts of the state. It wouldn’t be until Lewis Peacock was shot on June 13, 1871, that the feud finally ended.

When a crime is committed, it seems to take forever to bring justice for the victims. Sometimes people just don’t want to wait, or they are so mad about the crime committed against them or their family, that they decide, either consciously or unconsciously, to take matters into their own hands. This is known as vigilante justice, and while we still have it today, it really was more prevalent in the Old West….at least as it applies to storming the jail and hanging the “criminal” accused of the crime, without a trial.

When a crime is committed, it seems to take forever to bring justice for the victims. Sometimes people just don’t want to wait, or they are so mad about the crime committed against them or their family, that they decide, either consciously or unconsciously, to take matters into their own hands. This is known as vigilante justice, and while we still have it today, it really was more prevalent in the Old West….at least as it applies to storming the jail and hanging the “criminal” accused of the crime, without a trial.

Vigilante justice was more common in the wild west days because law enforcement was almost non-existent. Vigilantes took it upon themselves to “enforce the law,” as well as their own moral code, even if the event was not necessarily against the law. When a mob would decide that a prisoner is guilty, they would storm the jailhouse, drag the prisoner out, down the street to a big tree, and there they would hang the prisoner, whether they were guilty or not. The mob had decided. I suppose that a lot of times the person who was hanged was guilty of the crime, but without a trial and evidence to prove their guilt, how could anyone be sure?

The term vigilante stems from the its Spanish equivalent, meaning private security agents, but the vigilantes of  the old west and the mobs, who riot for their idea of right these days, have little in common with security agents. Most vigilantes and mobs are driven anger and adrenaline. Unfortunately those two things together don’t often bring a good outcome, and in the case of lynch mobs, it’s never a good outcome. Old West vigilantes were most common in mining communities, but were also known to exist in cow towns and in farming settlements. These groups usually formed before law and order existed in a new settlement. The justice dished out included whipping and banishment from the town, but more often, offenders were lynched. And sometimes the vigilante groups formed in places where lawmen did exist, but were thought to be weak, intimidated, or corrupt.

the old west and the mobs, who riot for their idea of right these days, have little in common with security agents. Most vigilantes and mobs are driven anger and adrenaline. Unfortunately those two things together don’t often bring a good outcome, and in the case of lynch mobs, it’s never a good outcome. Old West vigilantes were most common in mining communities, but were also known to exist in cow towns and in farming settlements. These groups usually formed before law and order existed in a new settlement. The justice dished out included whipping and banishment from the town, but more often, offenders were lynched. And sometimes the vigilante groups formed in places where lawmen did exist, but were thought to be weak, intimidated, or corrupt.

Some people see vigilantes as heroes, thereby giving them he support of some of the law-abiding citizens. Some people saw them as a necessary step to fill a much needed gap. Nevertheless, sometimes the vigilance committee began to wield too much power and became corrupt themselves. At other times, vigilantes were nothing more than ruthless mobs, attempting to take control away from authorities or masking themselves as “do-gooders” when their intents were little more than ruthless or they had criminal intent on their own minds. One of the first vigilante groups formed was the San Francisco Vigilantes of 1851. After several criminals were hanged the committee was disbanded. When the city administration, itself, became corrupt, a vigilante group formed once again in 1856. There were many vigilante groups formed in the American West. The Montana  Vigilantes who hanged Bannack Sheriff Henry Plummer in 1864. They controlled the press, so the sheriff was made out to be the leader of an outlaw gang called the Innocents. Further investigation indicates that it might have been the vigilante group, themselves, who were behind the chaos reigning in Montana and that Henry Plummer was an innocent man. Following the Civil War, the Reno Gang began to terrorize the Midwest, resulting in the formation of the Southern Indiana Vigilance Committee. The next time the Reno Gang attempted to rob a train, a the vigilante group lynched its leaders…Frank, William and Simeon Reno. Vigilantes did good in some instances, but it was not really the best form of justice.

Vigilantes who hanged Bannack Sheriff Henry Plummer in 1864. They controlled the press, so the sheriff was made out to be the leader of an outlaw gang called the Innocents. Further investigation indicates that it might have been the vigilante group, themselves, who were behind the chaos reigning in Montana and that Henry Plummer was an innocent man. Following the Civil War, the Reno Gang began to terrorize the Midwest, resulting in the formation of the Southern Indiana Vigilance Committee. The next time the Reno Gang attempted to rob a train, a the vigilante group lynched its leaders…Frank, William and Simeon Reno. Vigilantes did good in some instances, but it was not really the best form of justice.

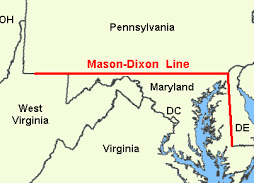

I think most of us have heard of the Mason-Dixon Line, but do we really know what it is and how it came to be called that? Maybe not. It was on October 18, 1767 that two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon completed their survey of the boundary between the colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as areas that would eventually become the states of Delaware and West Virginia. The Penn and Calvert families had hired Mason and Dixon, two English surveyors, to settle their dispute over the boundary between their two proprietary colonies, Pennsylvania and Maryland. The dispute between the families often resulted in violence between the colonies’ settlers, the British crown demanded that the parties involved hold to an agreement reached in 1732. In 1760, as part of Maryland and Pennsylvania’s adherence to this royal command, Mason and Dixon were asked to determine the exact whereabouts of the boundary between the two colonies. Though both colonies claimed the area between the 39th and 40th parallel, what is now referred to as the Mason-Dixon line finally settled the boundary at a northern latitude of 39 degrees and 43 minutes. The line was marked using stones, with Pennsylvania’s crest on one side and Maryland’s on the other.

I think most of us have heard of the Mason-Dixon Line, but do we really know what it is and how it came to be called that? Maybe not. It was on October 18, 1767 that two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon completed their survey of the boundary between the colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as areas that would eventually become the states of Delaware and West Virginia. The Penn and Calvert families had hired Mason and Dixon, two English surveyors, to settle their dispute over the boundary between their two proprietary colonies, Pennsylvania and Maryland. The dispute between the families often resulted in violence between the colonies’ settlers, the British crown demanded that the parties involved hold to an agreement reached in 1732. In 1760, as part of Maryland and Pennsylvania’s adherence to this royal command, Mason and Dixon were asked to determine the exact whereabouts of the boundary between the two colonies. Though both colonies claimed the area between the 39th and 40th parallel, what is now referred to as the Mason-Dixon line finally settled the boundary at a northern latitude of 39 degrees and 43 minutes. The line was marked using stones, with Pennsylvania’s crest on one side and Maryland’s on the other.

When Mason and Dixon began their endeavor in 1763, colonists were protesting the Proclamation of 1763, which was intended to prevent colonists from settling beyond the Appalachians and angering Native Americans. In reality, expansion was inevitable, but many in government couldn’t seem to see that. As the Mason and Dixon concluded their survey in 1767, the colonies were engaged in a dispute with the Parliament over the Townshend Acts, which were designed to raise revenue for the British empire by taxing common imports including tea. A protest that resulted in the Boston Tea Party, but that is another story. Twenty years later, in late 1700s, the states south of the Mason-Dixon line would begin arguing for the perpetuation of slavery in the new United States while those north of line hoped to phase out the ownership of human property. This period, which historians consider the era of “The New Republic,” drew to a close with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which accepted the states south of the line as slave-holding and those north of the line as free. The compromise, along with those that followed it, eventually failed, and slavery was forbidden with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862.

One hundred years after Mason and Dixon began their effort to chart the boundary, soldiers from opposite

sides of the line spilled their blood on the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the Souths final and fatal attempt to breach the Mason-Dixon line during the Civil War. One hundred and one years after the Mason and Dixon completed their line, the United States finally admitted men of any complexion born within the nation to the rights of citizenship with the ratification of the 14th Amendment…a poorly thought out amendment which continues to cause illegal immigration to this day, due to birth right citizenship.

sides of the line spilled their blood on the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the Souths final and fatal attempt to breach the Mason-Dixon line during the Civil War. One hundred and one years after the Mason and Dixon completed their line, the United States finally admitted men of any complexion born within the nation to the rights of citizenship with the ratification of the 14th Amendment…a poorly thought out amendment which continues to cause illegal immigration to this day, due to birth right citizenship.

Most people know what the United States Capitol building looks like, and many have seen it, and even been inside it, but I wonder how many people know that is almost wasn’t completed. Yes, you heard me right. I almost wasn’t completed. As a young nation, the United States had no permanent capitol, and Congress met in eight different cities, including Baltimore, New York and Philadelphia, before 1791. In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which gave President Washington the power to select a permanent home for the federal government. The following year, he chose what would become the District of Columbia from land that had been provided by Maryland. Washington picked three commissioners to oversee the capital city’s development and they in turn chose French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant to come up with the design. However, L’Enfant clashed with the commissioners and was fired in 1792. A design competition was held, and a Scotsman named William Thornton submitted the winning entry.

Most people know what the United States Capitol building looks like, and many have seen it, and even been inside it, but I wonder how many people know that is almost wasn’t completed. Yes, you heard me right. I almost wasn’t completed. As a young nation, the United States had no permanent capitol, and Congress met in eight different cities, including Baltimore, New York and Philadelphia, before 1791. In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which gave President Washington the power to select a permanent home for the federal government. The following year, he chose what would become the District of Columbia from land that had been provided by Maryland. Washington picked three commissioners to oversee the capital city’s development and they in turn chose French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant to come up with the design. However, L’Enfant clashed with the commissioners and was fired in 1792. A design competition was held, and a Scotsman named William Thornton submitted the winning entry.

Then, on this day, September 18, 1793, Washington laid the Capitol’s cornerstone and the lengthy construction process, which would involve a line of project managers and architects, got under way. One would think that is due time, the capitol building would be finished, but in reality, it took almost a century to finish…almost 100 years!! During those years, architects came and went, the British set it on fire, and it was called into use during the Civil War. In 1800, Congress moved into the Capitol’s north wing. In 1807, the House of Representatives moved into the building’s south wing, which was finally finished in 1811. During the War of 1812, the British invaded Washington DC. They set fire to the Capitol on August 24, 1814. Thankfully, a rainstorm saved the building from total destruction. Congress met in nearby temporary quarters from 1815 to 1819. In the early 1850s, work began to expand the Capitol to accommodate the growing number of Congressmen. The Civil War halted construction in 1861 while the Capitol was used by Union troops as a hospital and barracks. Following the war, expansions and modern upgrades to the building continued into the next century.

Today, the Capitol building, with its famous cast-iron dome and important collection of American art, is part of the Capitol Complex, which includes six Congressional office buildings and three Library of Congress buildings, all developed in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Capitol, which is visited by 3 million to 5 million people each

year, has 540 rooms and covers a ground area of about four acres. I’m sure that those who visit the United States Capitol Building probably hear all about it strange past and its construction history, but maybe not. I suppose that it depends on what the tour guide finds interesting. Personally, I like the unusual construction. Thankfully, the United States Capitol did finally get built and has become the beautiful building we know today.

year, has 540 rooms and covers a ground area of about four acres. I’m sure that those who visit the United States Capitol Building probably hear all about it strange past and its construction history, but maybe not. I suppose that it depends on what the tour guide finds interesting. Personally, I like the unusual construction. Thankfully, the United States Capitol did finally get built and has become the beautiful building we know today.

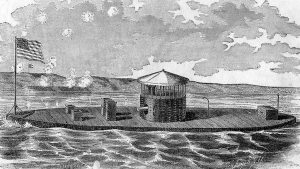

The worst fate a ship can suffer is to end up at the bottom of the sea. Nevertheless, it is a hazard that goes with the territory. Most of these lost ships simply litter the ocean floor, never seeing the light of day again, but once in a while, a ship…or part of a ship finds itself being raised up from the bottom again. Such was the case with USS Monitor, a Civil War era naval warship, that sunk to a watery grave in a storm on March 9, 1862, taking with it, 16 members of it’s crew, who were afraid to go topside in the storm.

The worst fate a ship can suffer is to end up at the bottom of the sea. Nevertheless, it is a hazard that goes with the territory. Most of these lost ships simply litter the ocean floor, never seeing the light of day again, but once in a while, a ship…or part of a ship finds itself being raised up from the bottom again. Such was the case with USS Monitor, a Civil War era naval warship, that sunk to a watery grave in a storm on March 9, 1862, taking with it, 16 members of it’s crew, who were afraid to go topside in the storm.

A short nine months before the tragedy of the USS Monitor, the ship had been part of a revolution in naval warfare. On March 9, 1862, it dueled to a standstill with the CSS Virginia in one of the most famous moments in naval history. It was the first time two ironclads ships faced each other in a naval engagement. During the battle, the two ships circled one another, jockeying for position as they fired their guns, but the cannon balls were no match for the ironclad ships, and they simply deflected off of the sides. In the early afternoon, the Virginia pulled back to Norfolk. Neither ship was seriously damaged, but the Monitor effectively ended the short reign of terror that the Confederate ironclad had brought to the Union navy. What a strange battle that must have been.

The USS Monitor was designed by Swedish engineer John Ericsson. Probably the most strange part of the design was the fact that Monitor had an unusually low profile, rising from the water only 18 inches. The ship sat so low to the water, that it could easily have resembled a submarine. The flat iron deck had a 20 foot cylindrical  turret rising from the middle of the ship. The turret housed two 11 inch Dahlgren guns. The shift had a draft of less than 11 feet so it could operate in the shallow harbors and rivers of the South. It was commissioned on February 25, 1862, and arrived at Chesapeake Bay just in time to engage the Virginia. After the famous duel with the CSS Virginia, the Monitor provided gun support on the James River for George B. McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign. By December 1862, it was clear the ship was no longer needed in Virginia, so she was sent to Beaufort, North Carolina, to join a fleet being assembled for an attack on Charleston.

turret rising from the middle of the ship. The turret housed two 11 inch Dahlgren guns. The shift had a draft of less than 11 feet so it could operate in the shallow harbors and rivers of the South. It was commissioned on February 25, 1862, and arrived at Chesapeake Bay just in time to engage the Virginia. After the famous duel with the CSS Virginia, the Monitor provided gun support on the James River for George B. McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign. By December 1862, it was clear the ship was no longer needed in Virginia, so she was sent to Beaufort, North Carolina, to join a fleet being assembled for an attack on Charleston.

The Monitor was an ideal type of ship in the sheltered waters of Chesapeake Bay, but the heavy, low-slung ship was no good in the open sea. Knowing that, the USS Rhode Island towed the ironclad around the rough waters of Cape Hatteras…a plan that would prove disastrous. As the Monitor pitched and swayed in the rough seas, the caulking around the gun turret loosened and water began to leak into the hull. More leaks developed as the journey continued. High seas tossed the craft, causing the ship’s flat armor bottom to slap the water. Each roll opened more seams, and by nightfall on December 30, it was clear that the Monitor was going to sink. That evening, the Monitor’s commander, J.P. Bankhead, signaled the Rhode Island that they needed to abandon ship. The USS Rhode Island pulled as close as safety allowed to the stricken USS Monitor, and two lifeboats were lowered to retrieve the crew. Many of the sailors were rescued, but some men were too terrified to venture onto the deck in such rough seas. The Monitor’s pumps stopped working, and the ship sank before 16 of its crew members could be rescued. It amazes me that a ship that could deflect cannon balls, was taken  down by loosened calking.

down by loosened calking.

On this day in 2002, the rusty iron gun turret of the USS Monitor rose up from the bottom of its watery grave, and into the daylight for the first time in 140 years. The ironclad warship was raised from the floor of the Atlantic, where it had rested since it went down in a storm off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, during the Civil War. Divers had been working for six weeks to bring it to the surface. The remains of two of the 16 lost sailors were discovered by divers during the Monitor’s 2002 reemergence. Many of the ironclad’s artifacts are now on display at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia.

Every war has one thing in common…there are two opposing sides. That can make for a volatile situation, even years after the war is over. Take our own Civil War. That war ended in 1865, but to this day, there are those who think we should tear down any and all memorials to the heroes of the South, which of course, lost the war. It’s a tough situation, but when you think about it, is a general from the South any less brave in battle. It is all a part of he fabric that forms our nation. They did not win the war, but as we have all told our children about sports, “It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you played the game.” Now, I know that war isn’t a game, although some have indicated that it is, nevertheless, most soldiers from the South fought as bravely and as honorably as those from the north. Everyone knows that the Confederate flag is not the flag of the United States, but it is a piece of it’s history, and history is history. It is not something we should be defacing, but rather honoring, because the fought the good fight.

Every war has one thing in common…there are two opposing sides. That can make for a volatile situation, even years after the war is over. Take our own Civil War. That war ended in 1865, but to this day, there are those who think we should tear down any and all memorials to the heroes of the South, which of course, lost the war. It’s a tough situation, but when you think about it, is a general from the South any less brave in battle. It is all a part of he fabric that forms our nation. They did not win the war, but as we have all told our children about sports, “It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you played the game.” Now, I know that war isn’t a game, although some have indicated that it is, nevertheless, most soldiers from the South fought as bravely and as honorably as those from the north. Everyone knows that the Confederate flag is not the flag of the United States, but it is a piece of it’s history, and history is history. It is not something we should be defacing, but rather honoring, because the fought the good fight.

President Regan felt the same way when he visited Germany on May 5, 1985. The Holocaust was a horrible  event, and not one that the majority of the German people agreed with, but they were in a difficult place too. They were following orders. Had they not done so, they would have been killed…here was no doubt. So, when Reagan went to Germany and to the cemeteries of the fallen German soldiers, should he have been disrespectful…of course not. He was a visitor in their country, and whether their politics was right or wrong, these were their fallen heroes. They were fathers, sons, brothers, uncles, grandfathers to someone in Germany, and they were loved. As Reagan said that day, “Here they lie. Never to hope. Never to pray. Never to love. Never to heal. Never to laugh. Never to cry.” Lives taken…too soon, by war, and that made them a nation’s heroes.

event, and not one that the majority of the German people agreed with, but they were in a difficult place too. They were following orders. Had they not done so, they would have been killed…here was no doubt. So, when Reagan went to Germany and to the cemeteries of the fallen German soldiers, should he have been disrespectful…of course not. He was a visitor in their country, and whether their politics was right or wrong, these were their fallen heroes. They were fathers, sons, brothers, uncles, grandfathers to someone in Germany, and they were loved. As Reagan said that day, “Here they lie. Never to hope. Never to pray. Never to love. Never to heal. Never to laugh. Never to cry.” Lives taken…too soon, by war, and that made them a nation’s heroes.

No two sides will ever agree, and emotions run high after a war, but sometimes people take things too far…retaliating for things they believe were wrong, years and even centuries after the events took place. The dead  are dead, and their memorials should be left alone, whether they are private, state, or national. To someone, somewhere, their efforts were heroic, and just because we have a different view of the things they stood for, does not give is the right to terrorize their graves and memorials. I suppose that many people would argue this point with me, and let it be known that I am not condoning the wrongs done by evil nations, I an simply saying that we should leave the memorials alone, because they do no harm. If people want to make a statement, they should teach their children right from wrong, so that they understand the difference between a cause, and a heroic soldier of that cause. One could arguably be condemned, while the other should not be.

are dead, and their memorials should be left alone, whether they are private, state, or national. To someone, somewhere, their efforts were heroic, and just because we have a different view of the things they stood for, does not give is the right to terrorize their graves and memorials. I suppose that many people would argue this point with me, and let it be known that I am not condoning the wrongs done by evil nations, I an simply saying that we should leave the memorials alone, because they do no harm. If people want to make a statement, they should teach their children right from wrong, so that they understand the difference between a cause, and a heroic soldier of that cause. One could arguably be condemned, while the other should not be.

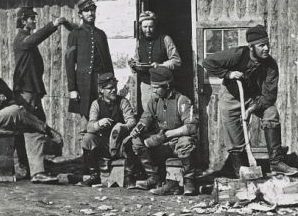

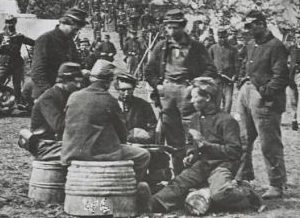

During the Civil War, the fighting was much different than these days…not just in the weapons used, but in a much bigger way. To send men out to battle in the winter was just too risky. Impassable, muddy roads and severe weather impeded active service in the wintertime. In fact, during the Civil War, the soldiers only spent a few days each year in actual combat. The rest of the time was spent getting from one battle to another, and wintering someplace because of bad weather. Even the rainy seasons caused problems, because rain brings muddy roads, and you can’t move heavy cannons on muddy roads. They get stuck. The soldiers tended to have a lot of time on their hands in the winter, and they couldn’t just go home either. In reality, disease caused more soldiers’ deaths than battle did.

During the Civil War, the fighting was much different than these days…not just in the weapons used, but in a much bigger way. To send men out to battle in the winter was just too risky. Impassable, muddy roads and severe weather impeded active service in the wintertime. In fact, during the Civil War, the soldiers only spent a few days each year in actual combat. The rest of the time was spent getting from one battle to another, and wintering someplace because of bad weather. Even the rainy seasons caused problems, because rain brings muddy roads, and you can’t move heavy cannons on muddy roads. They get stuck. The soldiers tended to have a lot of time on their hands in the winter, and they couldn’t just go home either. In reality, disease caused more soldiers’ deaths than battle did.

The soldiers sometimes kept journals of their time, which is where so much of the information we have about their time, came from. One such soldier was Elisha Hunt Rhodes. The winter months were monotonous for the soldiers. There was really nothing to do, but they needed to be kept in shape and at the ready, so the solution became days spent drilling. I’m sure that the boredom caused tempers to flair at times too, but the down time allowed the soldiers some time to bond and have a little bit of fun, as well. Nevertheless, the main objective for the winter months was to stay warm and busy, because their survival depended on it.

Rhodes was in the Army for four years, and he kept a journal for all of that time. He was a member of the 2nd Rhode Island Rhodes and fought in every battle from the First Bull Run to Appomattox. He rose from the rank of private to the rank of colonel in four years. According to Rhodes, the winter months were pretty quiet for the soldiers. They didn’t fight many battles, and so the months were spent drilling or smoking and sleeping. Some of the troops gambled and others drank or even visited the prostitutes who hung out around the camps. Believe it or not, the soldiers actually welcomed Picket Duty, which is when soldiers are posted on guard ahead of a main force. Pickets included about 40 or 50 men each. Several pickets would form a rough line in front of the main army’s camp. In case of enemy attack, the pickets usually would have time to warn the rest of the force. Picket Duty became a welcome break from the day to day monotony, because in Rhoades words, “One day is much like another at headquarters.”

Rhodes spent most of his winter months in or near Washington DC, giving him more diversions than some soldiers in the Civil War, who were in more remote locations. On one such trip into town came on February 26, 1862, he took the opportunity to hear Senator Henry Wilson from Massachusetts speak on expelling disloyal members of Congress. After listening to the speech, Rhodes and his friend Isaac Cooper attended a fair at a

Methodist church and met two young women, who the soldiers escorted home. Like other soldiers, Rhodes welcomed the departure from winter quarters and an end to the monotony. “Our turn has come,” he wrote when his unit began moving south to Richmond, Virginia,in 1864. His winter break was over, and he would find himself back in battle again. Rhodes would survive the Civil War and after a long life, passed away on January 14, 1917 at 75.

Methodist church and met two young women, who the soldiers escorted home. Like other soldiers, Rhodes welcomed the departure from winter quarters and an end to the monotony. “Our turn has come,” he wrote when his unit began moving south to Richmond, Virginia,in 1864. His winter break was over, and he would find himself back in battle again. Rhodes would survive the Civil War and after a long life, passed away on January 14, 1917 at 75.

During the Civil War, money was made out of silver and gold. People would not have trusted any other form of money, but having enough silver and gold to make that money wasn’t always easy. The Northern states needed money, and they knew they had to make it, but Congress and others were concerned for the economy. If the government made money without silver or gold to back it, wouldn’t it eventually doom the economy? Most of us would call that counterfeit money, and yet our government is still doing this at times, more than we want to think about. Nevertheless, if you are part of the government, or even just someone who understands how such money can effect the economy, you might very likely be against something like the Legal Tender Act that was passed by the US Congress on this day, February 25, 1862.

During the Civil War, money was made out of silver and gold. People would not have trusted any other form of money, but having enough silver and gold to make that money wasn’t always easy. The Northern states needed money, and they knew they had to make it, but Congress and others were concerned for the economy. If the government made money without silver or gold to back it, wouldn’t it eventually doom the economy? Most of us would call that counterfeit money, and yet our government is still doing this at times, more than we want to think about. Nevertheless, if you are part of the government, or even just someone who understands how such money can effect the economy, you might very likely be against something like the Legal Tender Act that was passed by the US Congress on this day, February 25, 1862.

This was a huge step. Prior to this time, the money was real money. It needed no proof that its value was real,  the people using it could see that for themselves. The United States didn’t have money that was basically an I.O.U. before that time. The problem was that they also had a war going on that cost a lot of money, and with people fighting the war, there were a lot less people to go out and look for gold and mine silver. It was a big problem, but the Civil War was extremely costly, and it had to be financed. The government had to face the fact that the supply of gold and silver was depleted. The Legal Tender Act was not a decision they came to lightly. They discussed every other option, including bonds. Once they settled on paper money, the Union government printed 150 million dollars in paper money…called greenbacks. The Confederate government had been printing money since the beginning of the war, which proved to be folly in the end, but I guess if the south had won, it would have gone the other way. Nevertheless, the bankers and financial experts predicted doom immediately, and many legislators worried that the money might collapse the infrastructure.

the people using it could see that for themselves. The United States didn’t have money that was basically an I.O.U. before that time. The problem was that they also had a war going on that cost a lot of money, and with people fighting the war, there were a lot less people to go out and look for gold and mine silver. It was a big problem, but the Civil War was extremely costly, and it had to be financed. The government had to face the fact that the supply of gold and silver was depleted. The Legal Tender Act was not a decision they came to lightly. They discussed every other option, including bonds. Once they settled on paper money, the Union government printed 150 million dollars in paper money…called greenbacks. The Confederate government had been printing money since the beginning of the war, which proved to be folly in the end, but I guess if the south had won, it would have gone the other way. Nevertheless, the bankers and financial experts predicted doom immediately, and many legislators worried that the money might collapse the infrastructure.

The greenbacks did not sink the economy. In fact, they worked very well. The government was able to pay its bills and, by increasing the money in circulation, the Northern economy actually improved. The greenbacks were legal tender, which meant that creditors had to accept them at face value. Life went on, but there were repercussions from the new money. In 1862, Congress was forced to pass an income tax and steep excise taxes, designed to cool the inflationary pressures created by the greenbacks. In 1863, another legal tender act was passed, and by the war’s end nearly half a billion dollars in greenbacks had been issued. The Legal Tender Act laid the foundation for the creation of a permanent currency in the decades after the Civil War.

Have you ever wondered why US money is green…or mostly green, while the money of so many other countries is very colorful? How did paper money come about anyway? Actually, paper money has been around in the United States since the beginning, off and on anyway. Printing paper money has been a controversial practice over the years. In 1861, as a means of financing the American Civil War, the federal government began issuing paper money for the first time since the Continental Congress printed currency to help pay for the Revolutionary War. The earlier form of paper dollars, dubbed continentals, were produced in such high volume that they soon lost much of their value. Devaluing our money has been a long standing problem with paper money. It’s simply too easy to print more money than we have gold to back.

Have you ever wondered why US money is green…or mostly green, while the money of so many other countries is very colorful? How did paper money come about anyway? Actually, paper money has been around in the United States since the beginning, off and on anyway. Printing paper money has been a controversial practice over the years. In 1861, as a means of financing the American Civil War, the federal government began issuing paper money for the first time since the Continental Congress printed currency to help pay for the Revolutionary War. The earlier form of paper dollars, dubbed continentals, were produced in such high volume that they soon lost much of their value. Devaluing our money has been a long standing problem with paper money. It’s simply too easy to print more money than we have gold to back.

In the decades before the Civil War, private, state chartered banks printed the paper money. Not surprisingly, this resulted in a wide variety of denominations and designs. Apparently, there was no real decision on how this should look. I guess they weren’t really worried about counterfeiting at that time. The bills that came out in the 1860s became known as greenbacks, because their backsides were printed in green ink. This ink was used as an anti-counterfeiting measure used to prevent photographic knockoffs, since the cameras of the time could only take pictures in black and white. I guess that counterfeiting had become a problem in the earlier years after all. And as we all know, the new scanners continue to improve the possibility of counterfeiting, making watermarks and security strips necessary too. And they have also added color to the money these days.

In 1929, the federal government decided that the paper money was too expensive to print, so in an effort to cut costs, they shrunk the size of all paper money. At the same time, they standardized the designs for each denomination, which made it easier for people to tell the difference between real and counterfeit bills. The new, more compact bills continued to be printed in green ink, because according to the US Bureau of Printing and Engraving, the ink was readily available and durable. They also thought that the color green represented stability. Today, there is some $1.2 trillion in coins and paper money in circulation in America. It costs about 5 cents to produce every $1 bill and around 13 cents to make a $100 bill, the highest denomination currently in

circulation. Don’t ask me why the difference, I would have expected them to be pretty much the same cost to manufacture. The estimated life span of a $1 bill is close to six years, while a $100 bill typically lasts 15 years, which makes sense to me, because we don’t use the $100 bill nearly as much. The $50 bill has the shortest average life span, at 3.7 years, and I would have expected the shortest lifespan to be the $1 bill, because we us those all the time.

circulation. Don’t ask me why the difference, I would have expected them to be pretty much the same cost to manufacture. The estimated life span of a $1 bill is close to six years, while a $100 bill typically lasts 15 years, which makes sense to me, because we don’t use the $100 bill nearly as much. The $50 bill has the shortest average life span, at 3.7 years, and I would have expected the shortest lifespan to be the $1 bill, because we us those all the time.

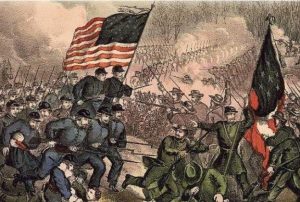

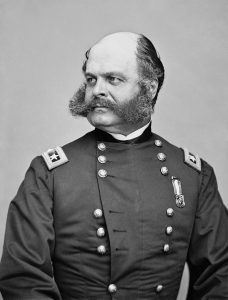

Those who have studied the Civil War, or know much about the United States at all, know that the Civil War was won by the Union, but that does not mean that there weren’t battles that they lost. There are very few wars that are lopsided in their battle field victories. One such battle was the Battle of Fredericksburg. On December 11, 1862, Ambrose Burnside, newly placed in command of the Army of the Potomac, planned to cross the Rappahannock River in Virginia with over 120,000 troops. When he finally crossed it, two days later, on December 13, 1862, he confronted 80,000 troops of Robert E Lee’s Confederate Army at Fredericksburg. With 200,000 combatants, this was the largest concentration of troops of any Civil War Battle. It was also one of the battles the Union Army would lose. In a crushing defeat, the Union Army suffered nearly 13,000 casualties, while the Confederate Army only lost 5,000.

Those who have studied the Civil War, or know much about the United States at all, know that the Civil War was won by the Union, but that does not mean that there weren’t battles that they lost. There are very few wars that are lopsided in their battle field victories. One such battle was the Battle of Fredericksburg. On December 11, 1862, Ambrose Burnside, newly placed in command of the Army of the Potomac, planned to cross the Rappahannock River in Virginia with over 120,000 troops. When he finally crossed it, two days later, on December 13, 1862, he confronted 80,000 troops of Robert E Lee’s Confederate Army at Fredericksburg. With 200,000 combatants, this was the largest concentration of troops of any Civil War Battle. It was also one of the battles the Union Army would lose. In a crushing defeat, the Union Army suffered nearly 13,000 casualties, while the Confederate Army only lost 5,000.

People might think that Burnside was not much of a commander, but it should be mentioned that this was the first time he had commanded an army. He was a graduate of West Point, had risen quickly up the ranks, and had seen action in several battles prior to this fateful day. Abraham Lincoln had approached him about taking control of the Union’s Army. He hesitated, partly out of loyalty to the current commander and former classmate, and partly because he was unsure of his own ability. In the end the prior commander’s failure assured that he was on the way out, and rather than have Major General Joseph Hooker, a fierce rival, pass him up, Burnside accepted the commission on November 7, 1862.

Knowing that he had to have the element of surprise, Burnside came up with a plan to confront Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Fredericksburg. He planned to move his forces to the banks of the neighboring Rappahannock River, and then transport his men across by way of hastily assembled pontoon bridges, and surprise the enemy. Lincoln was impressed with the audacity of the plan and approved it, but expressed doubts about its potential for success. Burnside swung into action, reaching the banks of the Rappahannock by November 19, 1862. We will never know if the plan might have succeeded, if some Union generals, including Winfield Scott Hancock, who believed the river could be crossed without the boats, had sent the boats…but instead, they urged Burnside to act without them. Burnside, who believed the river was too swift and deep, refused. They waited a week for the boats…unfortunately, under the watchful eyes of the Confederate scouts.

The element of surprise was gone. When they finally began building the pontoon bridges, the Confederate Army opened fire. Burnside began a massive bombardment of Fredericksburg, in the first shelling of a city in the Civil War. They were able to hold back the Confederate Army long enough to finish the bridges, and then they rushed across the river. Two days later, Burnside ordered his left flank to attack Lee’s right, in the hopes that Lee would have to divert forces to the south of the city, leaving the center and Marye’s Heights vulnerable. For a few hours, it looked like this might actually work. General George Meade broke through “Stonewell” Jackson’s line, but the Union failed to send in enough reinforcements to prevent a successful Confederate counterattack. Lee was able to keep James Longstreet’s men in position at Marye’s Heights, where they decimated Union forces. Burnside lost eight men for every Confederate soldier lost there. Though Burnside briefly considered another assault, the battle was over. The Union had suffered nearly 13,000 casualties while the Confederates lost fewer than 5,000. They needed to regroup before attacking again.

Burnside was an unpopular commander, partly I’m sure, because he felt the need to rush into things without really planning them out. His feelings of inadequacy proved to be his downfall. As he was planning his next attack, some of his leaders went to President Lincoln to voice their concerns. In the end, Lincoln halted the attack. On January 20, 1983, Burnside was ready to go again, but again the pontoon bridges were delayed. The weather didn’t help things either. What had been a dry January turned rainy, and the roads were all but impassible. Troops that had covered 40 miles a day on their way to Fredericksburg now struggled to get further than a mile. For three days, Burnside’s troops continued their disastrous slog on what would become known as the “Mud March,” accompanied most of the way by jeering Confederate forces taunting them from dry land. Five days after his offensive began, it was over…and so was Burnside’s brief, six week stint as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln immediately removed him from command, replacing him with the very person he feared it would be…Joseph Hooker.

Fredericksburg was the low point in the war for the North, but the South was ecstatic. Burnside probably should have stuck to his side career…weaponry design. And that was what he went back to. He retired in 1853 and in 1856 received his first patent for a .54 caliber breech loading firearm. Impressed with the carbine’s performance, the U.S. Army awarded the Bristol Firearm Company in Rhode Island…where Burnside worked…with a $100,000 contract. The order was soon rescinded, however, under shady circumstances. It’s believed that a rival munitions company bribed the army ordinance department to switch suppliers. Burnside’s bad luck continued the next year when a failed bid for a Congressional seat, followed closely by a fire that destroyed the Bristol factory, forced the financially strapped Burnside to sell his patents. Others would reap the rewards  when, at the start of the Civil War, demand for his creation soared. By 1865, more than 55,000 carbines had been ordered, and the Burnside had become one of the most popular Union weapons of the war, second only to the Sharp carbine and my ancestor, Christopher Spencer’s Spencer carbine.

when, at the start of the Civil War, demand for his creation soared. By 1865, more than 55,000 carbines had been ordered, and the Burnside had become one of the most popular Union weapons of the war, second only to the Sharp carbine and my ancestor, Christopher Spencer’s Spencer carbine.

Burnside would eventually have a claim to fame, but it would not be for war or weapons. Burnside liked to wear his facial hair in what was an unusual way for the times. He had a bushy beard and moustache along with a clean-shaven chin. These distinctive whiskers were originally dubbed “burnsides,” but later the term would be altered and would become “sideburns.”