bridges

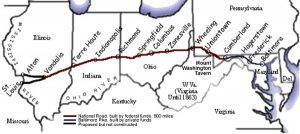

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to connect this young country. In 1806 Congress authorized construction of the road and President Jefferson signed the act establishing the National Road. It would connect Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio River. Construction on the road, known in many places as Route 40, and in others as the Cumberland Road, began in 1811 and continued until 1834. It was designed to reach the western settlements, and was the first federally funded road in United States history.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to connect this young country. In 1806 Congress authorized construction of the road and President Jefferson signed the act establishing the National Road. It would connect Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio River. Construction on the road, known in many places as Route 40, and in others as the Cumberland Road, began in 1811 and continued until 1834. It was designed to reach the western settlements, and was the first federally funded road in United States history.

The first contract was awarded in 1811, and included the first 10 miles of road. These days that seems like such a short distance, but in the early 1800s, I’m sure it was considered a big job. By 1818 the road was completed to Wheeling, West Virginia. It was at this point that mail coaches began using the road. By the 1830s the federal government turned over part of the road’s maintenance responsibility to the states through which it ran. In order to help pay for the road’s upkeep, tollgates and tollhouses were built by the states. As work on the road progressed a settlement pattern developed that is still visible. Original towns and villages that were found along the National Road, remain barely touched by the passing of time. The road, also called the Cumberland Road, National Pike and other names, became Main Street in these early settlements, earning the nickname “The Main Street of America.” The height of the National Road’s popularity came in 1825 when it was celebrated in song, story, painting and poetry, but hard times hit in 1834, and construction on the road was tabled. During the 1840s popularity soared again. Travelers and drovers, westward bound, crowded the inns and taverns along the route. Huge Conestoga wagons hauled produce from farms on the frontier to the East Coast, and then returned with staples such as coffee and sugar for the western settlements. Thousands of people moved west in covered wagons and stagecoaches that traveled the road keeping to regular schedules.

In the 1870s, however, the railroads came and some of the excitement of the national road faded. In 1912 the road became part of the National Old Trails Road and its popularity returned in the 1920s with the automobile. Federal Aid became available for improvements in the road to accommodate the automobile. In 1926 the road became part of US 40 as a coast-to-coast highway. As the interstate system has grown throughout America, interest in the National Road again waned. However, now when we want to have a relaxing journey with some history thrown in, we again travel the National Road. Cameras capture old buildings, bridges and old stone mile markers. Old brick schoolhouses from early years sporadically dot the countryside and some are found in the small towns on the National Road. Many are still used, some are converted to a private residence and others stand abandoned.

Historic stone bridges dot their way along the National Road, and they have their own stories to tell. The craftsmanship of the early engineers was amazing. The S Bridge, was so named because of its design and it stands 4 miles east of Old Washington, Ohio. It was built in 1828 as part of the National Road. It is a single arch stone structure. This one of four in the state is deteriorated and is now used for only pedestrian traffic. However the owners of the bridge are attempting to obtain funding for its restoration. The stone Casselman River Bridge still stands east of Grantsville, Maryland. It is a product of the early 19th century federal government improvements program along the National Road, the Casselman River Bridge was constructed in 1813-1814. Its 80-foot span, is the largest of its type in America, and it connected Cumberland to the Ohio River. In 1933 a new steel bridge joined the banks of the Casselman River. The old stone bridge, partially restored by the State of Maryland in the 1950s is now the center of Casselman River Bridge State Park. Mile markers have been used in Europe for more than 2,000 years and our European ancestors continued that tradition here in America. These markers tell travelers how far they are from their destination and were an important icon in early National Road travel. Kids ask what they are fr, and adults nostalgically seek them out for photographing. A drive through National Road towns usually reveals one of these markers, such as the one standing by the historic Red Brick Tavern in Lafayette, Ohio.

In the 1960s Interstate 70, bypassed Route 40 and much of the National Road, leaving many businesses by the wayside. People were looking for faster cars and quicker arrival times. Life runs at a much faster pace these

days. These old roads are a great way to relax, take your time and see some sights. Traveling the National Road, you can see the timeless little villages with small restaurants where you can get a home cooked meal and a trip back in time. The Interstate often parallels the National Road, but we leave behind the old inns and farmhouses in our rush to arrive about destination.

days. These old roads are a great way to relax, take your time and see some sights. Traveling the National Road, you can see the timeless little villages with small restaurants where you can get a home cooked meal and a trip back in time. The Interstate often parallels the National Road, but we leave behind the old inns and farmhouses in our rush to arrive about destination.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina came screaming into southeast Louisiana. It quickly set its sights on a large lake that many people in the rest of the United States probably didn’t even know existed, and those who did know, gave little thought to it. Nevertheless, Lake Pontchartrain was about to make national headlines, where it would remain for months to come. Hurricane Katrina and Lake Pontchartrain were about to make history. Together they were set to cause the music in the party town of New Orleans to stop. And it would be a long time before the people of New Orleans would feel much like singing. Nevertheless, the city of New Orleans would return to its former self again.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina came screaming into southeast Louisiana. It quickly set its sights on a large lake that many people in the rest of the United States probably didn’t even know existed, and those who did know, gave little thought to it. Nevertheless, Lake Pontchartrain was about to make national headlines, where it would remain for months to come. Hurricane Katrina and Lake Pontchartrain were about to make history. Together they were set to cause the music in the party town of New Orleans to stop. And it would be a long time before the people of New Orleans would feel much like singing. Nevertheless, the city of New Orleans would return to its former self again.

Bob and I were among those people who had really never heard of Lake Pontchartrain, and like us, if you didn’t know much about Lake Pontchartrain, you didn’t really understand the magnitude of the weakened levees. Hurricane Katrina brought heavy rain to Louisiana. Eight to ten inches fell on the eastern part of the state. In the area around Slidell even more rain fell. The highest rainfall recorded in the state was 15 inches. As a result of the rainfall and storm surge the level of Lake Pontchartrain rose and caused significant flooding along its northeastern shore, affecting communities from Slidell to Mandeville. Several bridges were damaged or destroyed, including the I-10 Twin Span Bridge connecting Slidell to New Orleans. Almost 900,000 people in Louisiana lost power as a result of Hurricane Katrina. In the end, at least 1,245 people died in the hurricane and subsequent floods, making it the deadliest United States hurricane since the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane.

Bob and I traveled to New Orleans in April of 2012. So many changes took place between August of 2005 and April of 2012. Nevertheless, I wasn’t sure how I felt about driving across that causeway that spanned Lake Pontchartrain. Yes, it had escaped damage in Hurricane Katrina, but it still crossed the widest part of a very large lake, and since I knew that the lake’s surges had the ability to severely damage it and the surrounding area…well, I just didn’t know how I would feel about the 23.83 mile drive across…not until we started across the bridge that is. It was an amazing bridge, and an amazing ride across it. The lake was serene, and I found myself hard pressed to picture the lake surging in the fury of a hurricane. I found it hard to picture the water so wild that it could damage a bridge, but it had happened…not to this bridge, but to others. The causeway bridge had been in use from it’s opening on August 30, 1956. At the time we were there, I had no idea of the length of the history of the Causeway. The idea of a bridge spanning Lake Pontchartrain dates back to the early 19th century and Bernard de Marigny, the founder of Mandeville. He started a ferry service that continued to operate into the mid-1930s.

After the 30s, and prior to the Causeway being built, people who lived in Covington and worked in New Orleans, had a very long commute to work. The bridge, while still 23.83 miles across the lake, took a large portion of that commute away. It was truly a great asset to the cities on both sides of the lake. Since 1969, the Causeway was listed by Guinness World Records as the longest bridge over water in the world. In 2011, when

the allegedly longer Jiaozhou Bay Bridge in China was built, Guinness created two categories for bridges over water…continuous and aggregate lengths over water. Lake Pontchartrain Causeway became the longest bridge over water (continuous), while Jiaozhou Bay Bridge the longest bridge over water (aggregate)…because of its sections that are over land. Even if the bridge does get replaced as the longest bridge, it will nevertheless, remain a very long bridge. And the drive over the bridge was as awe inspiring as it could be.

the allegedly longer Jiaozhou Bay Bridge in China was built, Guinness created two categories for bridges over water…continuous and aggregate lengths over water. Lake Pontchartrain Causeway became the longest bridge over water (continuous), while Jiaozhou Bay Bridge the longest bridge over water (aggregate)…because of its sections that are over land. Even if the bridge does get replaced as the longest bridge, it will nevertheless, remain a very long bridge. And the drive over the bridge was as awe inspiring as it could be.