b-52

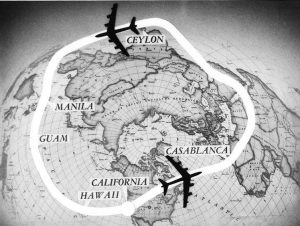

We all look for firsts in things, like first steps, first words, first man in space, first man on the moon, and in this case, the first around the world flight of a jet engine. You would expect that it might be some new jet, designed by an aviation expert, and you would be right, but the flight in question happened on January 16, 1957. The plans were three Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses. This was not just a flight for the purpose of setting a record, but rather it was a flight designed to prove a very important point. The operation was called Operation Power Flite…I’m not sure why flight was spelled flite. The planes made the trip around the world in 45 hours and 19 minutes, using in-flight refueling so that they could stay aloft for the entire journey. The mission was intended to demonstrate that the United States had the ability to drop a hydrogen bomb anywhere in the world. Led by Major General Archie J. Old, Jr. as flight commander, five B-52B aircraft of the 93rd Bombardment Wing of the 15th Air Force took off from Castle Air Force Base in California on January 16, 1957, at 1:00 PM, with two of the planes flying as spares. Old was aboard Lucky Lady III (serial number which was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James H. Morris, who had flown as the co-pilot aboard the Lucky Lady II when it made the world’s first non-stop circumnavigation in 1949. Heading east, one of the planes was unable to refuel successfully from a Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter and was forced to land at Goose Bay Air Base in Labrador. The second spare refueled with the rest of the planes over Casablanca, Morocco and then split off as planned to land at RAF Brize Norton in England.

We all look for firsts in things, like first steps, first words, first man in space, first man on the moon, and in this case, the first around the world flight of a jet engine. You would expect that it might be some new jet, designed by an aviation expert, and you would be right, but the flight in question happened on January 16, 1957. The plans were three Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses. This was not just a flight for the purpose of setting a record, but rather it was a flight designed to prove a very important point. The operation was called Operation Power Flite…I’m not sure why flight was spelled flite. The planes made the trip around the world in 45 hours and 19 minutes, using in-flight refueling so that they could stay aloft for the entire journey. The mission was intended to demonstrate that the United States had the ability to drop a hydrogen bomb anywhere in the world. Led by Major General Archie J. Old, Jr. as flight commander, five B-52B aircraft of the 93rd Bombardment Wing of the 15th Air Force took off from Castle Air Force Base in California on January 16, 1957, at 1:00 PM, with two of the planes flying as spares. Old was aboard Lucky Lady III (serial number which was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James H. Morris, who had flown as the co-pilot aboard the Lucky Lady II when it made the world’s first non-stop circumnavigation in 1949. Heading east, one of the planes was unable to refuel successfully from a Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter and was forced to land at Goose Bay Air Base in Labrador. The second spare refueled with the rest of the planes over Casablanca, Morocco and then split off as planned to land at RAF Brize Norton in England.

After a mid-air refueling rendezvous over Saudi Arabia, the planes followed the coast of India to Sri Lanka and then made a simulated bombing drop south of the Malay Peninsula before heading towards the next air refueling rendezvous over Manila and Guam. The three planes continued across the Pacific Ocean and landed at March Air Force Base near Riverside, California on January 18 after flying for a total of 45 hours and 19 minutes, with the lead plane landing at 10:19 AM and the other two planes following each other separated by  80 seconds. The 24,325 miles flight was completed at an average speed of 525 miles per hour and was completed in less than half the time required by Lucky Lady II when it made the first non-stop circumnavigation in 1949. General Curtis LeMay was among the 1,000 on hand to greet the three planes, and he awarded all 27 crew members the Distinguished Flying Cross. Though Old called the flight “a routine training mission,” the Air Force emphasized that the mission demonstrated its “capability to drop a hydrogen bomb anywhere in the world.” The flight was in reality, a warning to hostile nations, that the United States was capable of dropping a bomb anywhere in the world, and it would be for the best if these nations did not provoke the United States.

80 seconds. The 24,325 miles flight was completed at an average speed of 525 miles per hour and was completed in less than half the time required by Lucky Lady II when it made the first non-stop circumnavigation in 1949. General Curtis LeMay was among the 1,000 on hand to greet the three planes, and he awarded all 27 crew members the Distinguished Flying Cross. Though Old called the flight “a routine training mission,” the Air Force emphasized that the mission demonstrated its “capability to drop a hydrogen bomb anywhere in the world.” The flight was in reality, a warning to hostile nations, that the United States was capable of dropping a bomb anywhere in the world, and it would be for the best if these nations did not provoke the United States.

On December 13, 1972, peace talks with North Vietnam broke down, and President Richard Nixon announced that the United States will begin a massive bombing campaign to break the stalemate. Nixon was furious, and order the plans drawn up for retaliatory bombings of North Vietnam, and Linebacker II was the result. The bombings began on December 18, 1972 and continued until December 29, 1972. Beginning with American B-52s and fighter-bombers dropping over 20,000 tons of bombs on the cities of Hanoi and Haiphong. The United States lost 15 of its giant B-52s and 11 other aircraft during the attacks. North Vietnam claimed that over 1,600 civilians were killed. After eleven days of the massive pounding, the North Vietnamese agreed to resume the talks.

On December 13, 1972, peace talks with North Vietnam broke down, and President Richard Nixon announced that the United States will begin a massive bombing campaign to break the stalemate. Nixon was furious, and order the plans drawn up for retaliatory bombings of North Vietnam, and Linebacker II was the result. The bombings began on December 18, 1972 and continued until December 29, 1972. Beginning with American B-52s and fighter-bombers dropping over 20,000 tons of bombs on the cities of Hanoi and Haiphong. The United States lost 15 of its giant B-52s and 11 other aircraft during the attacks. North Vietnam claimed that over 1,600 civilians were killed. After eleven days of the massive pounding, the North Vietnamese agreed to resume the talks.

A few weeks later, the treaty was finally signed and the Vietnam War ended. This also ended the United States’ role in a conflict that seriously damaged the domestic Cold War consensus among the American public. The  impact of the so-called “Christmas Bombings” on the final agreement remains a question. Some historians have argued that the bombings forced the North Vietnamese back to the negotiating table. Others thought that the attacks had little impact, other than the additional death and destruction they caused. Even the chief United States negotiator, Henry Kissinger, was reported to have said, “We bombed the North Vietnamese into accepting our concessions.” The chief impact may have been in convincing America’s South Vietnamese allies, who were highly suspicious of the draft treaty worked out in October 1972, that the United States would not desert them. Despite the forced return to the table, the final treaty did not include any important changes from the October draft.

impact of the so-called “Christmas Bombings” on the final agreement remains a question. Some historians have argued that the bombings forced the North Vietnamese back to the negotiating table. Others thought that the attacks had little impact, other than the additional death and destruction they caused. Even the chief United States negotiator, Henry Kissinger, was reported to have said, “We bombed the North Vietnamese into accepting our concessions.” The chief impact may have been in convincing America’s South Vietnamese allies, who were highly suspicious of the draft treaty worked out in October 1972, that the United States would not desert them. Despite the forced return to the table, the final treaty did not include any important changes from the October draft.

I believe that the bombings were instrumental in bringing the North Vietnamese back to the table, but I sometimes wonder what the emotional impact was on the men involved in the bombings. It’s hard to wage war  at anytime, but when you think of the Christmas season, and all it stands for, I must have been terribly hard to drop those bombs and end the lives of so many on what should have been a joyous holiday. I’m sure the men thought of their own families and children too. Of course, I don’t know what the North Vietnamese did about Christmas, or if it was anything to them at all, but it was to our men, and it seems to me that it would be very hard to take lives on that day…especially when, in times past it seems like it was common practice to have a cease fire on that day, but then I guess that can’t always be the case. Someone somewhere would insist on breaking the day of peace, because that is what war is all about, after all.

at anytime, but when you think of the Christmas season, and all it stands for, I must have been terribly hard to drop those bombs and end the lives of so many on what should have been a joyous holiday. I’m sure the men thought of their own families and children too. Of course, I don’t know what the North Vietnamese did about Christmas, or if it was anything to them at all, but it was to our men, and it seems to me that it would be very hard to take lives on that day…especially when, in times past it seems like it was common practice to have a cease fire on that day, but then I guess that can’t always be the case. Someone somewhere would insist on breaking the day of peace, because that is what war is all about, after all.